Edward Teller

Edward Teller

He worked with Stan.

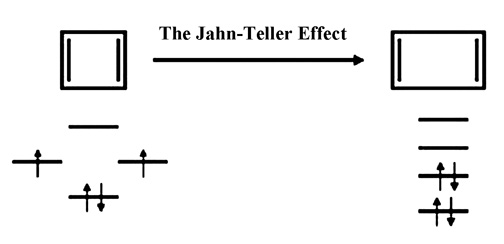

Perhaps Edward Teller should be best known for his fundamental work on quantum theory and molecular structure. After all, Edward - with fellow physicist Hermann Jahn - discovered the famous Jahn-Teller Effect which deals with molecules with "degenerate" ground states. No, no, no, we don't mean molecules that drink, carouse, and look at web sites they shouldn't. Instead, we mean molecules that have two or more ground states with the same energy. Edward and Hermann proved that for the most part, there are no such things.

Although the Jahn-Teller Effect is applied mostly to metal coordination complexes to explain distortions from the expected geometry or shifts from the expected spectra, it applies to all molecules where first approximation quantum calculations predict the molecule will not have a unique lowest energy state. The reason why the Jahn-Teller effect isn't usually taught in elementary chemistry classes is you would then realized that the explanations you learned in Organic Chemistry 101 about Hückel's 4n + 2 are off the beam, bullshine, and poppycock.

We won't go into details but simple quantum calculations tell us if you have 4n π electrons (that is, 4, 8, 12, etc.) in a cyclic molecule, then if you fill up the orbitals according to the Pauli exclusion principle, you end up with one electron in each of two different orbitals. Voila! you have a "diradical" which is unstable.

The Jahn-Teller Effect for Cyclobutadiene

Soddy, folks, almost as soon as Erich Hückel published his theory of the stability of cyclic conjugated organic molecules, Edward's effect demonstrated that the usual formulation of Hückel's rule is an oversimplification. For cyclic organic molecules with 4n π elections, the Jahn-Teller effect says the two non-bonded orbitals combine to form one filled bonding orbital and another unfilled anti-bonding orbital. Cyclobutadiene, then, is in fact a stable molecule - at least in the strict sense of the word. It is highly reactive, yes, but it won't fly apart if you send it up by itself into outerspace. You can learn more about how to properly predict stability of the these organic molecules, if you just click here. But since we're talking about Edward, not organic chemists, we'll go on.

As it is, many more people know about Edward than organic chemists. I mean, who are you going to remember? The originator of Woodward's Rules for ultraviolet spectra (Robert Burns Woodward), the Woodward-Hoffman rules of orbital symmetry (Robert and Roald Hoffman), extended Huckel theory (Roald), or semi-empirical quantum methods (Michael James Stuart Dewar), or:

THE FATHER OF THE H-BOMB!!!!

That's the way most people think of Edward.

History goes in cycles and although in the 1950's it became particularly fashionable to praise Edward about his inventing the H-Bomb. But with the youth rebellion of the 60's, Edward became a favorite figure to trash. Not only were his more hawkish anti-Soviet political views derided by hippies and others in the peace movement, his technical accomplishments were belittled as well - particularly those related to nuclear physics and engineering. Instead, we learn, the real credit should go to the Polish mathematician (and later naturalized US citizen) mathematician, Stanislaw Ulam.

Actually there are good arguments that Stan did come up with the design for a thermonuclear device that really, really worked since Edward's initial designs would not. But the design is called in toto the "Teller-Ulam" design, and Edward was the first scientist to really believe making an H-bomb was possible, worked on it first, and who stuck with it until it did work. In that sense, we really have to give the "father" title to Edward.

Stanlislaw Ulam

He worked with Edward.

And we must admit that professional historians have not always been kind to Edward, either. Part of this has been, well, historical. Academics after the war - tended to be of liberal bent, and during the flower power era of the 60's it became very unfashionable to have pushed for the H-bomb. Edward, on the other hand, has been pictured as a man who had an almost rabid obsession with fomenting the East/West arms race. Still, a lot of scientists of international reputation - such as Ernest O. Lawrence and Luis Alvarez - also advocated strong defense. But if anyone remembers Ernest it's as the man who built the first atom-smasher and Luis is known as the man who, with his son, Walter, first decided the dinosaurs were wiped out by a comet crashing into the earth. So why do so many people have a problem with Edward?

What did irreparable harm to Edward's standing was his testimony at the Congressional hearings that were being held to determine if J. Robert Oppenheimer should keep his security clearance. Oppie had been the scientific director of the Manhattan Project during World War II which developed the A-bomb. But Oppie's former associations with left wing organizations, communist sympathizers, and actual card-carrying communists - including his brother and wife - had made him suspect in the government echelons. He had, though, convinced his boss, General Leslie Groves, that he had put his left wings associations behind him. So after the war, Oppie found himself a hero and arguably the most famous man in the world. He immediately assumed a leading role in advising the US Government on its nuclear program.

Oppie, though, had begun to have misgivings about his role in the A-Bomb project, misgivings which Edward couldn't understand. Specifically Edward soon found himself actively opposing Oppie's recommendations of sharing scientific information with the Russians.

J. Robert Oppenheimer

He and Edward had their differences.

Actually Edward's and Oppie's differences went back to the early days of the atomic bomb research. In 1943 Edward joined the team Oppie had assembled at Los Alamos. Supposedly Edward thought he would be in charge of the theoretical physics division, but instead Oppie gave the head job to Cornell physicist, Hans Bethe. But when Oppie and Hans tried to get Edward to help out on the A-bomb, Edward had a different idea.

A little digression is in order. In 1938, the German chemistry professor Otto Hahn and his assistant Fritz Strassmann found if you bombarded uranium atoms with neutrons, you found small amounts of barium. Where the heck did it come from? Well, one of Otto's colleague, Lise Meitner, who was Jewish and had fled to Sweden, figured out that the neutron was absorbed by the uranium nucleus. This increased the atomic mass by one atomic unit making the nucleus unstable. So the nucleus fell apart into smaller nuclei, one of which was barium, probably the easiest element to detect by the methods available to chemists in the 1930's.

A while later, Louis Alvarez was at Berkeley getting his hair cut. He flipped through a newspaper and came on the story how that the atom had been split by Otto and Fritz. Without waiting for the barber to finish, Louis - presumably he paid the barber - ran to Oppie and blurted out the news. Oppie frowned. Nonsense, he said, went to the blackboard and - quote - "proved" - unquote - that the atom couldn't be split.

The next day Louis went to his lab and was able to quickly repeat the experiment. He didn't analyze the mixture like Otto did, but used a detector to capture the fission products. Looking at the oscilloscope, Oppie agreed the reaction was real and pointed out the reaction would produce more neutrons and so could start a chain reaction.

Within a few days of the news, physicists were talking about the possibility of making atomic bombs. Although it is possible to calculate the energy given off by an atom splitting using Albert Einstein's famous E=mc2 equation it can also be calculated by simple principles of electrostatic repulsion of like charges. What causes the energy release is that when the nucleus is split, the two nuclei that form are both positively charged but extremely close together.

Of course, everyone knows that if you have two particles with like charges they fly apart. But they also release energy. The amount released is the the same energy required to push the particles back until they touch.

Now, for one atom, that's not much - maybe 0.000000000005 calories. That is, a single atom falling apart will raise 1 gram of water 0.000000000005 degrees centigrade. That doesn't seem like much but 1 gram of uranium has about 2,500,000,000,000,000,000,000 atoms. If they all split that would give off as much energy as 12 tons of TNT.

However, a publication by Rudolph Peierls, a German physicist who was living in Britain, stated the critical mass of Uranium needed for a self-sustaining chain reaction was a lot - literally tons. So people thought an atomic bomb was not practical.

The problem was Rudolph was using an equation he developed - which worked fine - but he was also calculating what happened if you hit Uranium 238 with the neutrons. U238 has 92 protons in the nucleus and 146 neutrons. But most elements have other atoms with different numbers of neutrons. So chemically they are the same element, but have a different mass. These isotopes (as they are called) are still chemically the same element. But they have more or less weight depending on if they have more or less neutrons.

It was a friend of Rudolph's, Otto Frisch, an Austrian physicist who had also moved to Britain, who realized that it was not U-238 that was absorbing the neutrons and splitting. Instead, it was an isotope with a lower atomic weight, Uranium 235.

The likelihood of U235 splitting was about 10 times more than U238. That still didn't seem like enough to make any practical difference in making a bomb. But when Otto and Rudolph used the numbers for U235 in Rudolph's equation, the amount needed - instead of being tons - turned out to be about a pound - the size of a golf ball.

But there was one catch. You had to have U235 in more or less a pure form. And Uranium 235, though, accounts for less than 1 % of natural uranium. Could it be separated and isolated?

Again Otto sat down and did some calculations. He based his numbers on a separation where you made a gaseous compound of uranium and let it diffuse through a series of membranes. The higher atomic weight uranium will diffuse slower than the lighter U235. Not much slower, but if you had a series of membranes the purity of the U235 would increase with each pass. With a large - but still practical - plant, Otto found out you could make a few pounds of essentially pure U235 in a few weeks.

Maybe it was because - as Hans Bethe later pointed out - the development of the atomic bomb was largely an engineering project - Edward seemed to lose interest. Instead, he became intrigued on what he called a new super bomb. He learned about the possibility ever since he had had a lunch time discussion with Enrico Fermi, arguably the best physicist in history. It had been Enrico who had created the first sustained nuclear reaction at the University of Chicago.

When talking to Edgar in Chicago, Enrico had mentioned that the energy given off by nuclear fission - splitting the uranium atom - would be so great it might be able - not to split - but to fuse two hydrogen atoms. This wasn't hydrogen as we usually think of it, but the heavier isotope called deuterium. Deuterium was actually pretty easy to isolate and make into easily handled solid compounds.

Later, it was realized that if you made the casing of the bomb out of U238 - the common uranium isotope - the neutrons coming from the fusion reaction would be enough to make the atoms of the normally intractable U238 break apart. Such a bomb - at first called the Super - would produce an explosion on the scale of millions of tons of TNT.

That's what Edward wanted to work on. And when he went to Los Alamos, that's what he told Oppie.

At first Oppie argued against it. They needed Edward to work on calculations of the atomic bomb, not to go off on something that might not work ever and certainly not work in time to use in the present war. But it was clear Edward would either work on the Super or not work at all. Oppie finally acquiesced.

The situation at Los Alamos has given armchair psychologists a field day with Edward, saying it explains his future resentment and opposition to Oppie. Certainly from that time on, it seems that whatever Oppie was in favor of, Edward was against. So when the war was over and Oppie began to talk about things like disarmament, banning nuclear weapons, cooperation with the Russians, and such stuff, Edward thought his former boss had gone off the beam. Edward who as a young man in Hungary had seen first hand the worst side of Communism didn't trust the Russians as far as he could throw them. The only way to handle them was to carry a stick big enough to annihilate a major metropolitan area.

Eventually, Oppie's loyalty and suitability to be privy to the US nuclear secrets were questioned (President Truman even called him a "crybaby" for expressing remorse about his role developing the atomic bomb). Oppie himself admitted in his early days he had been a "fellow traveler" and had friends (and relatives) who were card carrying Communists. During the war, the FBI had shadowed him and once waited outside the door of his girlfriend's apartment while Oppie stayed the night. They also opened his mail and bugged his phone and office. Soon Oppie found he had plenty of enemies in the government who didn't want him around.

Eventually, Lewis Strauss, one of the commissioners of the Atomic Energy Commission, told Oppie they would be investigating him because of "derogatory" information in his file. After discussing various options with Strauss (pronounced "Straws") and not knowing he was being set up, Oppie decided to ask for a hearing to clear his name. A lot of Oppie's colleagues were called to testify and many - included General Groves - defended him. But when Edward took the stand, he said he found Oppie's views confused and contradictory, and he would personally prefer that the security clearance not be renewed. Oppie's security clearance was not renewed.

It's unlikely that Edward's testimony was critical or even that important in Oppie losing his clearance. Instead, what hurt Oppie the most was the so-called "Chevalier Incident". As best as we can tell - or at least in one version of the story - in early 1943, Oppie had been back home in Berkeley and had some friends over. This was his friend his friend and fellow faculty member, Haakon Chevalier (known as "Hoke") and Hoke's wife, Barbara. At some point Oppie went into the kitchen to mix his famous (and strong) martinis. Hoke followed and said he had been approached by a chemist working at a near-by Shell facility, George Eltenton, concerning "sharing" nuclear secrets with the Russians.

George, it turns out, was an enthusiast of the Soviet Union - so enthusiastic that he was suspected of being an out-and-out spy. This is not likely since his praise of the Soviet system was a never ending source of boredom for his car-pooling buddies. Years later one of the car poolers pointed out that if George had really been a spy he never would have been so open about the virtues of Russia.

As far as what really happened, there were four people in the house, Oppie and his wife, Kitty, and Hoke and his wife, Betty. All gave different accounts of what happened and whether Oppie and Hoke were alone or not (Kitty said she was with them during the conversation). But it is certain that Oppie put an end to the conversation in short order, and any further contact with the Russian was squelched.

Naturally, the idea that someone was trying to weasel information directly from Los Alamos workers was a big concern. Oppie finally decided to tell the head of the Manhattan Project, General Leslie Groves, about the conversation. He didn't mention it was Hoke who spoke to him. Later General Groves asked Oppie for more details. Oppie said that three members of the Manhattan project had been approached by someone trying to obtain atomic secrets. He did not personally know the person who tried to make the contact, he said, and did not want to divulge the name of the other workers or the person who approached him. At first General Groves did not press the matter. Later though the security officers go so concerned that Groves asked Oppie for more details, including the names of everyone involved.

Well, Opie said, the man who approached him was his friend Hoke. He made up the "cock and bull" story of three workers. He was the only one Hoke spoke to. He did not believe Hoke was acting in any clandestine manner and was just passing on a suggestion about legitimate collaboration. General Groves decided not to take the matter further.

Hans Bethe

Oppie put him in charge.

Well, Oppie's congressional hearing was in 1954, not 1945, and Joe McCarthy a year earlier had pegged Oppie as a Communist. The congressmen listening to Oppie and the others finally decided that Oppie either covered up and misled the security head of the Manhattan project, or he lied to General Groves, or he was lying to them. In any case, they said, Oppie was unreliable and shouldn't be privy to important state secrets. So in the end, for whatever reason, Edward got his wish. Oppie was never involved in nuclear work for the government again.

To this day no one knows what Oppie was talking about. One author thinks that the names of the "three workers people at Berkeley were Oppie, Ernest Lawrence, and Luis Alvarez. George had been approached by one of the Russian officials at the San Francisco embassy and suggested these three men be approached about sharing information. George then suggested all three men to Hoke who only really knew Oppie well. Hoke very well may have mentioned the others during the kitchen conversation.

So by talking about the "three scientists" Oppie was in fact trying to give General Groves the fullest information possible and still keep Hoke out of trouble. If this is what happened, Oppie could have cleared the matter up. But after ten years it's possible he simply didn't even remember the details of what he had told the security officers - until they pulled out memos where the three workers were mentioned.

In the past Oppie has been painted as the persecuted martyr to freedom, hounded by fanatical paranoiacs. That may be true as far as it goes, but when Oppie appeared before HUAC in 1949 - at a time when he was still held in the highest esteem by almost everyone - he was certainly a most welcome and cooperating witness. In answer to the various questions, he named as communists, suspected communists, fellow travelers, and leftists a number of his soon to be former friends and students.

Among the strangest of Oppie's testimony was regarding Bernard Peters, who had fled Nazi Germany before studying physics at Berkeley with Oppie. Oppie told the committee that Bernard was a Red. He couldn't be trusted. Bernard may have criticized Communists, yes, but because the Commies didn't advocate enough violence. Bernard, Oppie added, took part in street fights. Well, yes the street fights were against the Nazis but that still shows how dangerous and violent Bernard was. Why, when Bernard was arrested and taken to the Dachau concentration camp, he had used his "guile" to escape. How could you trust a man like that?

Edward wasn't the only person who found Oppie's statements confused and contradictory. Bernard certainly did, particularly when he lost his job as a direct result of Oppie's testimony. Understandably miffed, he wrote Oppie, demanding an explanation. He had never, he said, ever taken part in street fights against the Nazi's, although he wished he had. But he had never been a member of the Communist Party, as Oppie knew full well. So how could Oppie have made up and testified to such drivel? Oppie had no really satisfactory answer because there really wasn't one.

Oppie may have gotten a walk for naming names and being a cooperative witness, but Edward sure didn't. For the rest of his long life, Edward found himself repeatedly asked about his testimony in the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer. Even in old age, he usually answered with patience, pointing out that he was giving testimony under oath, and an oath put limits on the way he could testify. Even when discussing other topics, Edward could be a bit testy and he once walked out of an interview with 60 minutes host, Mike Wallace.

Johnny Von Neumann

A Rational Opponent

As time went on, Edward became more and more positive about nuclear power in general and nuclear weapons in particlar. They could be a boon to mankind. Why, they could do anything, and as he once said to a colleague:

Do you want to find out more about moon dust? Explode a nuclear weapon on the moon and analyze the spectrum of the resulting dust. Do you want to excavate harbors or change the course of rivers? Nuclear weapons can do the job!

Given that Edward knew of the health effects of radioactive fallout, it's no surprise that some of Edward's colleagues began to think he was becoming a bit nuts.

With such unbridled enthusiasm for nuclear weapons, many people were flabbergasted when after the war Edward went on record that he felt the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had been wrong. Or at least there should have been a demonstration of the bomb's power. But that does not appear to be his thinking at the time. Not only was he not a signatory of the famous "Franck Report" which advocated just that, but he told Leo Szilard that the best way to insure the weapon would not be used again was to drop it on a real target. For what it's worth, Oppie favored (or at least agreed with) the bomb's military use without prior warning.

Edward's arguments for a strong defense ultimately had support of the originator of game theory, Johnny Von Neumann. Against a rational opponent, they argued, beginning a war that would result in complete annihilation of both sides is indeed a deterrent against starting the war.

That's a rational opponent.

References

Edward Teller: The Real Dr. Strangelove, Peter Goodchild, Harvard Univesity Press (2005). The only real biogrpahy of Edward to date. Edward does, though, feature prominantly in many other books about the history of the A- and H-bombs.

The Making of the Atomic Bomb, Richard Rhodes, Simon and Schuster, (1986) The most comprehensive history of the history of the Atomic Bomb but with much about Edward's interest in what was then called the "Super".

Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb, Richard Rhodes, Simon and Schuster, (1996). What it says, the history of the making of the hydrogen bomb. A more convoluted tale since the Russians were also making their own bomb but this details Edward's and Stan's collaboration - and competition.

American Prometheus: The Triumph and tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer, Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, Knopf (2006). A good book about Oppie and also tells of his dealings - often difficult - with Edward.

In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer: The Security Clearance Hearing, Richard Polenberg, Cornell University Press (2002). A number of books about Oppie use the basic title hear as it was the ominous introduction in one of the security committee's minutes.

"The many tragedies of Edward Teller", The Curious Wavefunction, Ashutosh Jogalekar, January 14, 2015. Web.

"Predictions of Molecular Geometries and Electronic Spectra of Complex Unsaturated Molecules from MC-LCAO-MO Method. II. 1,3-Butadiene and Cyclobutadiene", Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan, 49 (6), pp 1502-1507 (1976). One of a number of papers that show cyclobutadiene is not as simple Huckel theory states and which specifically cites the Jahn-Teller effect.

Return to Edward Teller Caricature