A Most Merry and Illustrated History of

The Life and Trial(s) of Lizzie Borden

A Most Merry and Illustrated Probabilistic, Legal, and Scientific Analysis

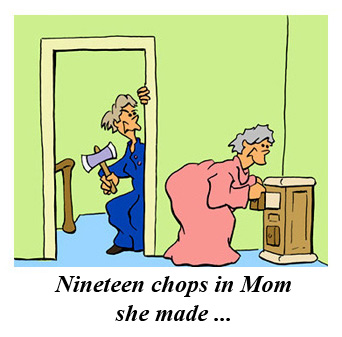

Lizzie Borden Took a Blade

Lizzie Borden took a blade

And nineteen chops in Mom soon made.

She gave Pa ten and cried, "I'm done!"

As history counts, that's eighty-one.

Yes, yes, this may not be as catchy as the tradition doggerel, but point of fact, Lizzie Borden did not take an axe and give her mother forty whacks, nor when she saw what she had done, give her father forty-one.

First of all she probably used a hatchet, not an axe. She whacked her mom, Abby - her stepmother actually - a total of nineteen times; her dad, Andrew, a mere ten. But even that was overkill (no joke intended). One or two chops would have done the job nicely, thank you.

And according to the rule of law, Lizzie didn't do it. She was acquitted. In those days, civil law had not advanced to where the case could be retried in civil court with its looser criteria for conviction. So when Lizzie got off, that was that. Legal historians, though, tend to be a bit harder on Lizzie than the all-male jury. Their consensus - although by no means unanimous - is she did it.

All right, then. Why would Lizzie Borden - a young Victorian woman of modest demeanor and decorum, an active member of the local Congregationalist Church, and who had probably done nothing worse than shoplift from local merchants, steal money and jewelry from her parents, and behead her stepmother's cat - want to chop up her parents? Just because she had come to detest her stepmother? And why should she have such a rage at her father? Just because he had recently gone out to the barn and chopped off the heads of all of Lizzie's pigeons?

Like all disagreements between friends and family the real cause of the discord was money. Andrew had been transferring some of his assets (mostly property) to the Durfees, that is, to Abby's family. Lizzie and her older sister, Emma, were now afraid they might end up realizing a substantially reduced inheritance. Worse, they were afraid that when Andrew got around to writing his will, he might even give everything to Abby. Then the girls would have to trust to the generosity of their stepmother, who, as we said, they didn't like, and who didn't like them.

Andrew, their dad, had long been a solid citizen of Fall River, Massachusetts, which even then was a heavily industrialized city about forty miles south of Boston. And Andrew was rich. Serving as the president of the Union Savings Bank and director of four other companies, he was easily worth at least a cool million nineteenth century bucks - probably more. Were he to die now without a will - intestate, in legal jargon - all his money and property would go to the girls IF (and it is a big IF), Abby packed it in at the same time.

By now the girls also knew they had no prospects for getting out of the house and starting a family of their own. With all their Pa's wealth, you would think there would be a never-ending line of young swains a-calling on the girls. After all, when they were young, Emma and Lizzie had been pleasant enough looking, if not ravishing beauties, and in their late teens and early twenties, they might even have been dubbed "cute". But the word was that Pa had always discouraged any prospective gold diggers paying court to his sweet young heiresses. Now Emma was in her forties and beginning to look a bit severe, and Lizzie, always a bit on the chubby side, was thirty-two and getting stout. It was clear they would end their days as full time spinsters, and they needed their dad's money to keep their jobs.

So doing away with her dad and stepmom had some rough logic to it. But carving them up does seem a bit extreme. And that probably wasn't Lizzie's idea in the first place. Instead, a case of stomach flu may have given her the idea to first try a more civilized approach.

Lizzie Asks for Some Gas

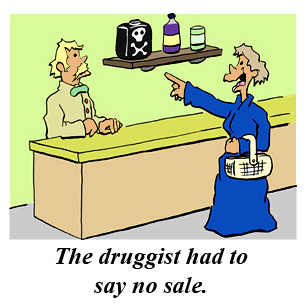

Lizzie Borden asked for gas

So she could wax her parents' ass.

But when the druggist heard her tale

He knew it had to be no sale.

Actually it wasn't really gas as we think of it, but a two percent water solution of a very specific gas - hydrogen cyanide. Known as "Prussic acid" in the old fashioned detective stories ("Ah, ha! The scent of bitter almonds!"), a small dose of HCN really can do you in.

What is really odd, given the modern

megaconcern with toxic chemicals, is that in Lizzie's day Prussic

acid - along with other poisons like strychnine, belladonna, and of

course, alcohol - was also considered a medicine. Grab an old dusty

medical text from around 1900 and you'll read it's a cure for spasms,

nervous irritability, severe vomiting, diarrhea, spasmodic coughs,

asthma, hysteria, chorea, dyspepsia, diseases of the skin, the cough

of consumptives, cardiac palpitations, hypertrophy of the heart,

angina, difficulty in breathing, and congestive headache. Of course,

you can always argue that since dead people don't suffer from those

ailments in that respect the textbooks didn't lie. And even the old

books hasten to add that due to its volatility, its proneness to

decomposition, and its variability of strength, Prussic acid will

very frequently "disappoint the expectations of the practitioner", by

(among other things) "inducing fatal symptoms." And so, kids, DON'T

try this at home - or anywhere else.

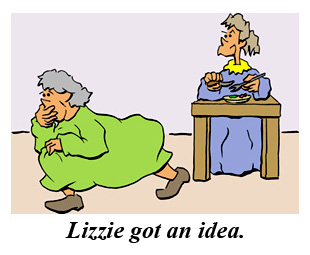

So once Lizzie decided to snuff her folks, she got what seemed to be a pretty good idea. Both Abby and Andrew had been sick the last day or so. From the progression of the symptoms through the household it was likely stomach flu, although some people think that Andrew, who tradition has labeled a tightwad, was just making everyone eat too many leftovers.

But Abby was afraid they had been poisoned. She never said why she thought that (she never had the chance), but Lizzie later said she had heard her dad arguing with some man, implying her dad had some enemies. That may have even have been true.

Anyway, after a day or so of heaving out in the backyard (the proper Victorian place to puke), Abby went across the street to their family physician, Dr. Seabury Bowen. She told him she was afraid they had been poisoned. Dr. Bowen laughed and said it wasn't poison and prescribed some castor oil laced with a bit of wine.

When Lizzie learned about Abby's visit to the doctor (which her father grumped he wouldn't pay for), she realized that a dime's worth of Prussic acid in the milk would wipe both Andrew and Abby out. She could then say her dad's rather vaguely defined enemy did the deed, and Dr. Bowen would unwittingly supply the supporting testimony. Then Lizzie and Emma could split their Pa's dough and live happily ever after.

So Lizzie went off to one of Fall River's many drugstores. When she walked in there were two clerks , Frederick Hart and Eli Bence. And Kilroy was there. That, is a young medical student, Frank Kilroy, was inside talking to Eli.

Lizzie went to the counter and asked Frederick for ten cents of Prussic acid. The reason, she said, had something to do with a sealskin cape, maybe cleaning it or keeping bugs off it or something. Before Frederick could answer, Eli stepped up and said they could only sell Prussic acid by prescription.

Here Lizzie's incriminating behavior really begins. She lied. She said she had bought it before with no problem. Sorry, Eli reiterated, but he could only sell it on a doctor's orders. So Lizzie looked around a bit and left, as Eli said, in a "haughty" manner. Although Eli didn't know Lizzie personally, he did know she was Andrew Borden's daughter. The visit also stuck in the minds of the other two men who clearly remembered Lizzie as the lady who wanted the poison. But despite the subsequent statements of Eli, Frederick, and Frank, Lizzie later denied trying to buy anything.

Was it suspicious that Lizzie tried to buy the Prussic acid? Not necessarily. Lying to Eli about how she bought it before? Maybe. Continuing to deny it despite the statements of three eyewitnesses? Very.

And as for the Eli's, Frederick's, and Frank's testimony, it was excluded from the trial on motion of the defense.

Score: Lizzie, 1. Prosecutors, 0.

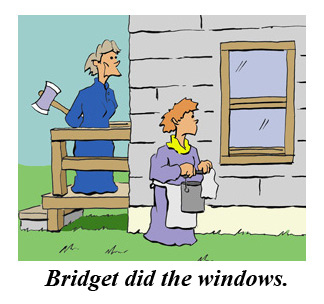

Bridget Does Windows

Bridget armed with cloth and pail

Washed the windows, says the tale.

When Pa went out, and Ma stayed in,

Soon the whacking would begin.

The next day, Thursday, August 4, 1892, Lizzie came downstairs around 8:00. Usually the girls rose later - around 9:00 - and ate separately from their parents. Today it was just Lizzie. Emma had gone off to visit friends earlier in the week and wasn't due back for a while. Despite the general dislike between the girls and Abby, they usually maintained the semblance of cordiality, and the chit-chat that morning was routine.

The Bordens' live-in maid, Bridget Sullivan (called by the girls "Maggie") had also come down with what had been ailing Abby and Andrew. When she got up she wasn't feeling so hot and even once went outside to throw up. Still Abby asked her to wash the windows if she felt up to it. So around 9:00, she got the rags and bucket and went outside.

When Bridget walked down the steps, Lizzie stepped to the door and asked if she was going to be washing windows. Bridget said yes and Lizzie could lock the doors if she wanted. She would get the water from the barn. It may seem funny that in the middle of an industrial town that even then had 75,000 inhabitants, a house would have a barn. But back then a barn was what you had in place of a garage.

Perhaps the oddest thing about the Bordens (if you ignore the murders) is they really did have a thing about locks. In an era before houses had pre-canned air, and people often kept their doors and windows wide open around the clock to let in the breeze, the Borden's kept their house shut up tighter than a drum. They never went out without locking up even if someone was home. The front door had three - count 'em three - locks, and the last thing Andrew picked up (literally) was another lock. So maybe Andrew really did have some enemies other than his youngest daughter.

But for now Lizzie knew that Bridget would be outside for about forty-five minutes. Lizzie could be alone in the house with Abby with the doors locked from the inside. There would be plenty of time to ... well, plenty of time to do a lot of things.

When Bridget started on her windows, Andrew had already gone out. His workday did not appear too onerous. He stopped at his bank for about five minutes - talk about banker's hours - visited some his tenants, and went to the barber's for a shave. Then he found the discarded lock, picked it up, and decided to take it home.

Back at the house Abby went upstairs to put on some pillow shams in the guest room. The day before John Morse, Andrew's brother-in-law from his first marriage (and so was Lizzie's and Emma's maternal uncle) had shown up unannounced. He spent the night and left that morning around 7:30 to visit other relatives. Although John was (and is) also suspected by some of being the real killer, his alibi was strong. He also got along with Andrew and Abby very well, and he's not really a serious candidate.

Lizzie Borden Chops Mom Up

Lizzie Borden chopped Mom up.

Smashed in her head like a China cup.

And if you think that was bad.

What she did for Mom, she did for Dad.

At this point according to our scenario, the action is brief. Lizzie, hatchet in hand, followed Abby upstairs. What (if anything) was said between daughter and stepmother is lost to history. But it probably wasn't much.

As Lizzie walked in, Abby turned toward her stepdaughter and immediately got the first whack of the day. It was upside the head and if it didn't knock her out (or worse), it at least knocked her down. From the posture of the body, we can guess she may still have been conscious and instinctively turned face down for protection. If so, that was fine with Lizzie, who standing astride her stepmother, began to flail away at the back of her head. Eighteen more chops and she figured the job well done. She was correct.

There are, though, problems with this scenario although it remains the most probable one. Certainly, the required technical finesse raises some questions. Although there were nearly a hundred splats of blood in the room - on the wall, on the dresser, and on the bed - Lizzie was clean. The question, then and now, was whether she could have had time to hose down both herself and the hatchet so thoroughly that the best forensic tests of the day couldn't detect any blood.

The answer is, yes, probably, even though by the 1890's forensic chemistry - and chemistry in general - was surprisingly advanced. By the late nineteenth century, chemistry was still largely an empirical science, but the foundations of its modern structural theory have been laid down, and chemical purification and analysis were using many techniques that are still used today. In a day where medical textbooks told doctors to prescribe carcinogens like chloroform or deadly poisons like Prussic acid for a persistent cough, what you read in chemistry texts is basically correct. It may sound rather quaint, but it's still correct.

Blood could be detected by a variety of chemical methods. One of the most popular was called the guaiacum (pronounced GWEYE-uh-cum) test. To run the test, you need the resin from the guaiacum tree, specifically the guaiacum officinale, an evergreen found in Central and South America. You heat the logs, let the resin run out, and allow it to harden. Then you grind it up and dissolve it in alcohol, thus making what is called a guaiacum "tincture" (as in tincture of iodine). You then add in a few drops of the blood sample (as a dilute water solution) followed by a couple of drops of hydrogen peroxide in diethyl ether.

Now if the sample is blood - that is if hemoglobin is present - you get an immediate and intense blue sapphire color. Other substances which turn blue (such as some iron compounds), we are told, do so much more slowly and the blue color is not the same.

In the first Sherlock Holmes story, "A Study in Scarlet", Sherlock trashed the guaiacum test, calling it "clumsy and unreliable". That comment, and his claim that microscopic examination for blood cells is useless after a few hours, makes you wonder how Sherlock ever solved a case. Of course, he never did, not being a real person. In fact, the guaiacum test is quite good, and even now is used in some screening tests, not only for blood, but in other diagnostics as well.

Ironically, it's the forensic textbooks of the era that teach us how to analyze for the blood that also tell us how Lizzie managed to get away with it. When running the chemical tests, one of the problems was getting the blood into water. The easiest samples to analyze are, as might be expected, fresh blood on cloth. There you simply suspended the bit of cloth by a thread in a test tube of cold water. If fresh, essentially all of the blood would pass into the water and even settle toward the bottom. If you took the cloth, rinsed it, and tried to do the test again, you wouldn't detect any blood.

It was important, though - and clearly so

stated in the textbooks - you need to use cold water. Hot

water, as every housewife knows, can "set" a bloodstain, essentially

dying the cloth. Lizzie, as a stay-at-home proper Victorian lady who

chopped up the occasional steak in addition to her parents, certainly

knew this. So if she got splashed with bits of Abby, then all she had

to do was to get a pail of cold water and quickly wash out the

stain.So the scenario - at least regarding her mom - is

Lizzie had plenty of time and could easily have washed off the

splashed blood.

Of course there's the favorite theory of the sex-sells crowd that Lizzie doffed her duds to do the deed. This is a theory both old and titillating (no pun intended) and which even dates back to the time of the trial. Of course, when Lizzie's story was made into a television movie starring Elizabeth Montgomery (Samantha of the TV series "Bewitched") this scenario was almost de rigueur since they wanted to attract a good audience. Actually, it wasn't a bad movie, although Hollywood did - as always - invent some parts to make it relevant for the audience of the times.

But it probably wasn't necessary for Lizzie to go prancing and jiggling about the house like a Bacchanalette dancing in the blood of her sacrificial victims. She owned ten dresses, eight of them blue and close to to what she put on that morning. She could have washed out the stains and switched to a similar dress, knowing that in the confusion of finding dead people lying about, Bridget might not notice the changes in shades of tint and design.

But even that may not have been necessary. The true quantity of blood - as the attending physicians said - wasn't really that much, and there would have been plenty of time for the rinsed areas of Lizzie's dress to dry to the point where it wouldn't attract attention. To be on the safe side, she could change in the afternoon to another dress. Then when things simmered down she could burn the original dress and make it look like a routine chore of house cleaning. In fact, as we'll see, that's exactly what she did.

But regarding her dad, the answer isn't so clear-cut (again no joke intended).

Lizzie and Her Pap

Lizzie Borden met her Pap

And thought he might like a nap

He lay down on couch, not bed

And soon was missing half his head.

By 10:30, Lizzie was downstairs ironing handkerchiefs, Bridget had finished the windows, and Abby was upstairs, deader than a doornail.

As Bridget came through the kitchen, Lizzie asked if she was going out. Bridget said probably not. She still wasn't feeling too good and decided to go upstairs and lay down. By the way, Lizzie said, Mrs. Borden had gone out. She had received a note that said someone was sick. Lizzie didn't know who it was.

Before Bridget went upstairs, Andrew returned. It was around 10:45. Since he was trying to open a door closed with three different types of locks, he had some problem getting in. Bridget heard the door rattle and opened it from the inside. She also had trouble with the door and at one point let out an exasperated "Pshaw!" Just then she heard Lizzie's laugh come from upstairs.

When Lizzie saw her dad she again told him how Mrs. Borden got a note and went out to visit a sick friend. Her dad said, fine, he was going to take a nap. According to Lizzie she helped him settle down on the couch and folded his coat up to use as a pillow.

Now note the time here. Between 10:45 and 10:55 (when Bridget went upstairs) Lizzie told both Bridget and her dad Mrs. Borden had gone out - and not a word about her coming back in. This is a crucial point in figuring out what Lizzie's original plan was, and we'll be contrasting this to her later statements about Abby getting back home.

Once more Lizzie was trying to get Bridget out of the house. As Bridget was heading upstairs, Lizzie told her that there was a sale on downtown. Cloth for dresses was going at eight cents a yard, bargain rates. Bridget didn't take the rather obvious bait, although she hinted she might go later. Then she went to her room.

After lying down for about five minutes, Bridget heard the town clock chime. It was 11:00. Ten minutes later she heard a cry from Lizzie.

Lizzie Calls for Help

Bridget heard a loud halloo!

Lizzie's Pa was split in two!

Someone smacked him, smacked him hard!

And where was Lizzie? In the yard!

"Maggie!" Lizzie called. "Come down quick! Father's dead. Someone came in and killed him!"

Bridget ran down the back stairs and found Lizzie standing with her back to the kitchen door. Bridget started to go into the sitting room.

"Maggie!" Lizzie cried. "Don't go in! I have got to have me a doctor!" Maybe she figured when the doctor was done checking her out, he could also look in on Andrew.

"Miss Lizzie, where was you?" Bridget asked. When she was excited sometimes her grammar wasn't so good.

"I was out in the yard," Lizzie replied and added the first of her absolutely ludicrous and contradictory explanations of what happened. "I heard a groan and came in and the screen door was wide open!" That must have been quite a groan to carry from a room halfway down the side of the house to the back yard. It got even more ridiculous since she later said she was up in the barn. That really must have been a groan. But it didn't matter because in her final version, she again said heard nothing and just walked into the room and found her dad chopped up. But whatever noise there was sure hadn't been from Andrew, not with half his face chopped away

One thing to keep track of is how often Lizzie kept changing her story. She told Bridget about hearing the groan when she was out in the yard. But when the investigation officially got underway, she told one of the policemen she hadn't heard a thing. Then she told someone else she heard a "distressing noise" (whatever that meant) and even later she said it was a "sound like a scrape". Then she went back to her story she hadn't heard a thing and went to the barn for twenty minutes only to find Andrew hacked up when she came back in.

But now in addition to wanting a doctor, Lizzie also asked Bridget to fetch her friend, Alice Russell. "I can't be alone in the house," she explained, immediately shoving Bridget out the door.

Figuring she had to look her best when reporting a murder, Bridget got her hat and shawl and ran across the street. Dr. Bowen wasn't home. But his wife said she expected him back at any moment. She'd send him right over. Bridget went on to find Alice.

A long time neighbor, Adelaide B. Churchill, saw Bridget scurry off down the street. Bridget was running and "looked scared", she said. Adelaide then saw Lizzie was standing at the back door.

"Lizzie," Adelaide called, "what is the matter?"

"Oh, Mrs. Churchill, do come over," Lizzie answered and then added one of the few true statements she made that day. "Someone has killed Father."

Adelaide came over and found Lizzie was sitting on the back stairs. Adelaide asked where Abby was.

"I don't know," Lizzie replied. "She had got a note to go see someone who is sick." Then once more overplaying her hand, she added, "But I don't know but she is killed, too, for I thought I heard her come in." Adelaide then asked Lizzie where she had been when her father was being puréed.

"I went to the barn to get a piece of iron", Lizzie said, adding it was to fix a screen. Of course, she already had a piece of iron with a three and a half inch cutting edge. But again she kept changing her story. Later it was tin. Then it was lead for sinkers although she hadn't gone fishing in five years.

"Shall I go and try to find someone to go and get a doctor?" Adelaide asked. Once more, although Lizzie couldn't be alone, she said yes, and sent the only other (living) person in the house out the door.

When Bridget got back with Alice, they found Dr. Bowen was sitting with Lizzie and Adelaide. Dr. Bowen went in to look at Andrew. He later said Andrew's appearance gave him quite a jolt, physician though he was.

Andrew was lying with his face resting on his coat that had been rolled up to use as a pillow. Dr. Bowen also saw his position was as Andrew usually took his catnaps - on his side with his feet on the floor. That meant, he reasoned, Andrew had been asleep and was killed by the first blow. But as with Abby the whacking didn't stop there. Andrew ended up with a total of ten slices, and Dr. Bowen could barely recognize his former patient. He went out to report the matter.

At this point we need to take note of Andrew's use of his coat. Without doubt the best argument for Lizzie's innocence was there was no blood on her, and she only had about a ten minute window to clean up after Andrew was hacked about - not the thirty to forty minutes she had with Abby. In the minds of many - and it is a reasonable objection - Lizzie could not have done it.

But there is a problem. A proper Victorian

gentleman like Andrew would not normally come home on a hot

August day and use his coat as a pillow, even for an impromptu - but

in this case, permanent - nap. He'd hang it up on the hall

rack.

There are three points to note. First, there is the quite reasonable explanation (in fact, one suggested by the prosecutors) that Andrew had hung his coat up as he normally would have done. Then when he began to snooze, Lizzie wrapped on her dad's coat backwards, surgeon fashion as it is, and whacked away. When the splattering was done, she simply took the coat off, rolled it up, and put it under his head, effectively hiding Andrew's blood with Andrew's blood. In fact, one of the doctors admitted that a similar garment kept his clothes from getting stained during surgery, although we assume he used a scalpel, not a hatchet, for his work.

Secondly, if there was ever a room made for an axe (or hatchet) murder, it was the Borden's parlor. Particularly if the intended victim was asleep on the couch. The door from the dining room was right by - that's right by - the couch. Hitting the gentleman from the back would minimize the splatter (as the expert witnesses called it) toward Lizzie, and if Andrew was indeed killed by the first blow, then the (again in scientific terminology) spurting would also be minor.

Finally, the crime scene photos show that a pillow - most likely placed by Lizzie as she settled her dad in - stuck up easily a full foot above his head. This would easily have provided a cushion (literally) and rebounded the splash away from anyone smacking Andrew and who was standing by the door. Once more a careful look at all the facts show that Lizzie - with a little luck - could have done it.

By now Lizzie was showing surprising powers in knowing what had gone on. Bridget said she wished she knew where Mrs. Borden was.

"Maggie," Lizzie said, "I am almost positive I heard her come in." Then rising to even greater heights in the ability to throw suspicion on herself, she asked, "Won't you go upstairs and see?" We'll show later, though, this whole "I-heard-Mrs.-Borden-come -in" shtick had to be complete and total baloney. In any case, Bridget said she wasn't going upstairs by herself. Adelaide said she'd go with her.

So with a great deal of trepidation, the two ladies crept up the stairs. When their heads poked just above floor level, they stopped and looked around. Peeking into the guest room, they could see underneath the bed. The room was dark, but something was on the floor between the far side of the bed and the wall. Bridget didn't think it was a mat; after all, they didn't have five foot three, two hundred pound floor mats in the house. When she ran up the stairs and into the room she found it wasn't. It was Mrs. Borden.

Soon the house was swarming. There were friends, neighbors, reporters, and doctors. Even the mayor came over, for crying out loud.

Oh, yes. The cops came too.

Lizzie Borden Took a Hatchet

Lizzie Borden took a hatchet,

Not a hacksaw, drill, or ratchet.

Now that Ma and Pa were ripped

Her alibi was? A fishing trip!

From what she said in her contradictory statements which changed whenever she found they weren't working, it's possible to figure out what might have been Lizzie's original plan. It was really pretty simple. She'd whack her folks and then say the ubiquitous "mysterious stranger" - the favorite culprit for attorneys defending guilty clients - came in and chopped them to pieces. The best laid plan would have been to lure Bridget out of the house, leaving Lizzie plenty of time to hack up her dad and to clean up. Then she would go out, making sure she was seen around town.

Once she got back she (or Bridget) would "discover" the crime. No one would suspect that the church-going Lizzie would do such a dastardly deed, and with the approximate timing, someone might even swear they had seen Lizzie out and about. Unfortunately Bridget didn't follow the script. She was home when Andrew got back. And she went upstairs, not out. So Lizzie had to do a quick rewrite. But the basics were the same. She stepped out, someone else stepped in and gave the proverbial nineteen and ten whacks that did her parents in.

As crazy as the idea sounds now, it actually worked - for a little while. Dr. Bowen told Lizzie it was a good thing she was outside or she would have been killed too. When the Fall River Herald printed the story they even suggested that Abby was an eyewitness to Andrew's murder, and the killer chased her upstairs before doing her in.

The problem was Lizzie had yet to work out the bugs out of her story. Since killing people with a hatchet was noisy, she figured she had to claim she was outside. Eventually she lit on the line that she had gone to the barn to look for lead sinkers for her fishing trip. After not finding any sinkers, she sat down and ate some pears freshly plucked from their tree.

Originally, though, she fumbled about. It wasn't lead sinkers, it was the tin or iron for a screen. And she wasn't too clear on the timing at first. She was out maybe about twenty minutes. Or maybe it was fifteen; or was it thirty?

Later, though, she became dogmatic about the time, particularly when Bridget (with a little help from the cops) was able to pinpoint the time of Andrew's - and what was first thought to be Abby's - demise as between 10:55 to 11:10. Lizzie then said she was out of the house for twenty minutes. No more no less. Not fifteen, not twenty-five. Twenty.

And to look for sinkers and eat pears it took twenty minutes? Lizzie just said she didn't like to do things in a hurry.

There was one thing that Lizzie hadn't thought

through. Although she had had a good practical knowledge for washing

out fresh bloodstains, she didn't know much about methods for

determining time of death. Nor was she aware of the calibre of the

expert witnesses, which included one of the nation's top forensic

scientists, that would be called in on the case.

The medical examiner of Fall River (Bristol County actually) was Dr. William F. Dolan. He was a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania Medical School and (for the time) a perfectly capable physician.Dr. Dolan carried out the autopsies of Andrew and Abby, for want of a better location, downstairs on the kitchen table. Comparing his autopsy reports to those written today (if you want to spend you time doing that type of stuff), they read surprisingly modern and detailed.

Dr. Dolan also took bits and pieces of Abby and Andrew (including their stomachs) and shipped them off to Harvard medical school for Dr. Edward Wood to look at. Dr. Wood, himself a physician, was one of the country's top forensic scientists and specialized in chemical analysis. Then about a week after Andrew and Abby were buried, Dr. Dolan and two other physicians went out to the cemetery and performed a much less agreeable second autopsy and came away with the elder Bordens' heads. From a recent discovery it turns out that, the various parts of the Bordens were never reunited, although they did make it to court.

Dr. Dolan also sent Dr. Wood what was claimed to be the murder weapon. During the search the cops came across two hatchets. One was a "clawhammer" type, but this was eventually ruled out. The other was a regular hatchet where the handle had been broken at the head - it looked like a fresh break, too - and was strangely covered with ashes. There were also some suspicious looking stains, and there was a reddish hair stuck on the blade as well. This didn't look good for Lizzie.

But Dr. Wood found that the stains were not blood. Furthermore, the hair was not human - probably from a cow.

Once more the lack of blood argues in Lizzie's favor. However, the handle - before it was broken - was quite smooth, and Dr. Wood said that cold water could have cleaned it up. But if the blood had gotten onto the broken part, he added, then the type of scrubbing needed would itself have left its mark. Reasonable explanations? First, the hatchet was broken to make disposal easier - but after the crime. Or it could have been broken by accident in the course of the investigation. Later testimony revealed the cops had found the handle with the hatchet. But during the course of the investigation - and much to the prosecution's embarrassment - it had gotten lost.

More recently there has been some additional and less speculative evidence that this was the hatchet used in the murders. Thomas Mauriello, Adjunct Professor in the University of Maryland's Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice and Tom Lange, a retired homicide detective from Los Angeles, were given access to the hatchet and Abby's scarf, both of which are held by the Fall River Historical Society. Except from the expected slices in the scarf, it was surprisingly good shape for a more than century year old piece of cloth. Many of the tears were long slices where the weapon had sliced and ripped the fabric. But the men found that one cut that looked like it was a direct hit. When Professor Mauriello inserted the edge of the hatchet into the tear, it fit perfectly.

The doctors also examined Lizzie's dresses and found, like the hatchet, there was no blood on them. Or, well, that's not entirely true. On one of Lizzie's underdresses there was a pinpoint of blood - one sixteenth of an inch across. The defense attorneys (validly) argued this meant nothing and dismissed the spot as an indication Lizzie was simply having her monthly distress. Lizzie, perhaps out of modesty, had another explanation. She said she had fleas.

But Dr. Wood was also sent bits of the carpet from the two rooms and by running experiments was able to test how fast blood coagulated on the Borden's carpets. The difference between the appearance of Abby's and Andrews' blood completely gibed with the other time indicators like the extent of digestion in their stomachs and the relative body temperatures and stiffness. From all the evidence the experts all came to surprising agreement about when Andrew and Abby were done in. Reasoning, despite attempts by modern Lizzie-was-innocent advocates to claim otherwise, that remains valid using current forensic guidelines.

Abby was killed between 9:00 and 9:30, right after Bridget went outside. So much for Abby leaving the house to visit a sick friend, much less Lizzie hearing Abby come in.

And Andrew? Well, the experts said he was chopped up at about 11:00, a conclusion that really didn't require much brainpower. In other words, Andrew was killed an hour and a half to two hours after Abby. Unfortunately (for Lizzie), the expert's testimony was so credible that neither defense nor prosecution seriously questioned it.

OK. Now pick the scenario you prefer. If you think Lizzie didn't do it, then here's what you have.

Bridget goes outside to wash windows. While Lizzie's in the kitchen, a killer comes to the Borden home, sneaks by the maid outside, goes into a house that is always locked, finds his way upstairs, and hacks up a 200 pound woman up so quietly that the stepdaughter who is merrily ironing handkerchiefs downstairs doesn't hear a thing. Then the killer either hides in the house for two hours or leaves unobserved and then sneaks back in. Then just after the maid goes upstairs, and the daughter goes outside to look for iron or tin or lead, the killer literally comes out of the woodwork, hacks up the father, and slips out again.

That's what the defense claimed.

If Lizzie did it?

She waits until she and her stepmother are the only ones in the house. Lizzie then kills Abby. Next Andrew gets back, and Bridget goes up to her third floor bedroom. Then Andrew lies down for a nap, and Lizzie kills him.

You decide.

The police suspected Lizzie almost from the first. Although in the beginning she had put on something of a show of the damsel in distress, it wasn't very convincing, and the officers quickly saw that Lizzie was the calmest person in the house. Bridget, Alice, and Adelaide were all about to flip out, but when she was questioned, Lizzie was calm and collected. She really didn't seem to give a flying hoo-hah that she had two parents who were now the main evidence for a murder investigation.

The police weren't alone in their suspicion. Some of Lizzie's family also thought there was trouble right there in Fall River City. Hiram Harrington, Andrew's somewhat estranged brother-in-law, didn't buy Lizzie's story of helping her Pa lie down on the couch, adjusting the shutters, and practically tucking him in. He believed Lizzie's attitude toward her Pa was more as a bitchy, temperamental, and underfunded princess rather than the solicitous and adoring daughter. When she got ticked off at her Pa - which was often - she would go for days without talking to him. As far as Hiram was concerned, the killer was someone in the household and given the circumstances that meant Lizzie.

But Lizzie had her revenge. In later years if anyone asked who killed her folks, she always said it was Hiram.

>Fall River's Finest Called to the Case

Fall River's finest were called to the case

And went to the Borden home, post-haste!

Lizzie bade them, "Do not fail!"

"Just ignore that blood there in the pail."

The first policeman at the scene was Fall River Patrolman George Allen. Chief Marshal Rufus B. Hilliard had gotten word that something was wrong chez Borden and sent George to see what was going on.

George said he got to the Borden's around 11:19 after leaving the police station at 11:15. George was quite certain about his timing, and this helps pinpoint that Andrew could not have been chopped up past 11:10. It also complete agrees with what Bridget said.

On the way there George asked a citizen, Charles Sawyer, to come with him. At the house, they were met by Dr. Bowen, and Charles stood by to guard the door. Within a few minutes another policeman, William Medley showed up and around 11:45, Patrolman John Fleet was on the scene.

The officers briefly questioned Lizzie as to where she was when her parents were being hacked to death, and they got her now standard reply that she was outside. William began to search the house. Except for Abby and Andrew lying around battered and bloody, everything seemed normal.

There was one thing, though. In the wash cellar William came across a bucket of water. Of course, a bucket of water in a wash cellar is no big deal, but there were also some towels there covered in blood. He asked Lizzie about them.

Oh, she said, it was "all right". She had told the doctor about them. The pail had been there two or three days. Nothing to worry about, really. Forget it.

William then talked to Dr. Bowen. But all Dr. Bowen said about some blood soaked towels in a pail of water in a house where two people had been butchered had been fully explained to his satisfaction. Presumably it was Lizzie who did the explaining.

Next William questioned Bridget. She said she

didn't know anything about the towels or pail. But she knew they

hadn't been sitting there for two or three days (as Lizzie said).

William, perhaps not as sharp as he could have been, didn't pursue

the matter further.

Dr. Bowen was definitely acting a bit strange. A couple of hours later the officers decided to make a top to bottom search the whole house. Lizzie had now retired to her room, and the cops figured that was the first place they should search. They knocked on the door, and it opened a crack. But rather than Lizzie, it was Dr. Bowen who stuck his nose out.

What did they want, he asked the cops. What did they want? To search the room, of course. Dr. Bowen then shut the door, talked with Lizzie sotto voce and again opened the door a crack. Well, Dr. Bowen asked, did they really have to search the room just now? For crying out loud, they said, a double murder had been committed. Of course, they had to search the room. Dr. Bowen shut the door again, and then after a few seconds let the men in. The reason for the delay, he said, was Lizzie was upset.

The police found nothing in Lizzie's room except her closet full of dresses. Some of them were old and ragged, but none were bespattered with Abby or Andrew. So the men went on to another part of the house.

Was Dr. Bowen simply trying to give Lizzie some treatment for her ordeal (as Lizzie claimed) or was he helping Lizzie hide incriminating evidence (as some speculate)? Who knows? But more of Dr. Bowen was to come.

Other officers had now arrived, among them Patrolman Philip Harrington (no relation to Hiram). He was in the kitchen when Dr. Bowen came in with some paper in hand. Philip asked what he had there, and Dr. Bowen gave an oddball answer.

He "thought", he said, it was nothing. Or well, maybe it had something to do with his daughter "going through somewhere". Philip noticed the word "Emma" was written on the page, but despite Dr. Bowen's incomprehensible answers, he didn't asked to look at the papers. Dr. Bowen then calmly lifted the lid to the stove and tossed the papers in.

So what the heck was going on? Individually each little episode might have an innocent explanation, but collectively it sure looks like Dr. Bowen was hiding something. Yes, the doctors who checked out Abby and Andrew did have to wash their hands. That could have explained the bucket and the towels. But it doesn't really square with Bridget's answers or the apparent timing or with what Lizzie and Dr. Bowen said (or rather didn't say). But burning the paper was certainly suspicious behavior, and there's never been a good explanation - or at least not an entirely innocent one - given.

Cutting Dr. Bowen some slack, we should remember that he was Lizzie's doctor, after all. He had known her since she was a little girl, and he may have naturally felt protective toward her, particularly since by now he had to suspect that she was the killer.

But would a physician want to hide his suspicions that a patient may have been a hatchet murderer? After all, there's one famous case when a family minister urged a parishioner to confess to a crime where he killed his mother, father, and his sister. Confess, of course, provided he was really guilty (he was, and he did).

Dr. Bowen, though, may have had other good and plenty reasons to protect Little Lizzie. There was definitely talk in town that Lizzie and Dr. Bowen had been - ah - "keeping company", so to speak. One time Lizzie's folks had gone off on a visit while Emma was also off somewhere. During that time Lizzie and Dr. Bowen had been seen out together and had sat with each other at church. Innocent association of a family friend and a solicitous physician? Maybe. But when the neighbors commented that Lizzie was a brave young woman to stay at home all by herself for a week or more, others, more worldly-wise, nodded sagely that with Dr. Bowen just across the street, maybe Lizzie wasn't so home alone after all.

Lizzie Pleads Her Case

Lizzie Borden pled her case

She was innocent, good, kind, and chaste.

The judge, though, didn't buy her tale.

And threw her butt in the Fall River jail.

On August 9th, five days after Andrew and Abby were killed, the official inquest was held. Criminal magistrate Josiah Blaisdell presided and District Attorney Hosea Knowlton did the questioning. Lizzie testified for four hours and gave answers that were contradictory and ambiguous, even accounting for the fact that each day Dr. Bowen was giving her a double dose of morphine.

Lizzie was followed by her uncle John Morse and then by Emma. Next came Dr. Bowen, Adelaide, Uncle Hiram, the impromptu front-door guard Charles Sawyer, two (and soon to be former) friends Agusta Tripp (it's spelled Agusta) and Alice Russell, Lizzie's aunt Sarah Whitehead, and a lady who made cloaks for Lizzie named Hannah Gifford. The ladies generally gave a picture of a rather tense family where the girls didn't like their stepmother and would trash Abby when talking to others, but had at least an unspoken truce in their day-to-day living.

Finally there were the three guys from the drugstore, Eli Bence, Frank Kilroy, and Frederick Hart. All said Lizzie tried to buy poison and were certain of their identification. The papers noted during this testimony that Lizzie's demeanor was "haughty" as she continued to deny she tried to buy poison. Other than the testimony of Lizzie herself, Eli's, Frank's, and Frederick's statements were probably the most damaging to Lizzie.

The inquest ended on August 11, and the Judge ruled Lizzie was "probably guilty". Reportedly wiping away a tear, he ordered her arrest.

The Trial(s) of Lizzie Borden

Lizzie Borden came to trial

Sat in the court without a smile.

Blue dresses? Yes! But no shoes that fit.

So the jury said, "We must acquit!"

Lizzie's trial began on July 5, 1893 - nearly a year after Andrew and Abby were killed. From the time she was arrested, August 11, until June 20, 1893 when she was acquitted, Lizzie was in jail, either in Fall River or in Taunton which was eight miles to the north.

It could have been worse. When in Fall River she was not kept in a cell but in the matron's (ergo, female jailer's) quarters. And after she was transferred to Taunton she was allowed out from time to time to take walks. So Lizzie found jail wasn't all that onerous. Today, it is true, she probably would have been granted bail (she could certainly have afforded it), but on the plus side, she didn't have to pay for any living expenses for nearly a year.

Actually, Lizzie came close to getting off without a trial. Despite the judge's tearful ruling, when the grand jury was convened on November 7, they did not return an indictment. It very well may have stayed that way except Lizzie's friend, Alice Russell, suddenly had a crisis of conscience. It turns out she knew something that had a bearing on the case, as they say, but had been keeping her mouth shut. Finally, though, she went to the prosecutors.

Three days after the murders Alice had been in the Borden's kitchen when Lizzie came in carrying a dress. Emma was there and asked Lizzie what she was going to do.

"I'm going to burn this old thing up," Lizzie said, "It is covered with paint." As with most of her dresses this one was blue, just like the one she wore the day of the murders. She took the lid off the stove and tossed the dress in.

Alice said, "I'm afraid, Lizzie, that the worst thing you could have done was to burn that dress. I have been asked about your dresses."

"Oh, what made you let me do it?" Lizzie asked, as if it was all Alice's fault.

Alice's testimony did two things. First it finally gave the grand jury the final impetus it needed to issue the murder indictments. And second, it pretty much put scotched the friendship between Lizzie Borden and Alice Russell.

But one thing Lizzie had now was money, and she also was able to pick the best lawyers money could buy. One was William H. Moody, then relatively young, but a very sharp guy who eventually would rise to the US Supreme Court. William, though, was officially the second in command. The head attorney - clearly a "prestige" choice - was George D. Robinson, a former governor of Massachusetts. He was also, by golly, the guy who appointed the chief judge at Lizzie's trial.

It can't be denied that her high priced attorneys - George got $25,000 nineteenth century dollars for his fee - did a heckuva job. Even at the time George's performance was likened to a marksman shooting down - not always successfully - the clay pigeons pitched up by the prosecutors. George got the experts to admit the assailant would probably be splattered with blood, which within the narrow time window that Andrew got dispatched, gave the jury what might be called reasonable doubt whether Lizzie did it.

As always the attorneys tried to show that the opposing witnesses were unreliable, and they had a fine time contrasting what a witness said now with how they testified at the inquest. That there contradictions was expected since people were being asked to remember what they saw or said nearly a year earlier. And it was kind of ridiculous to read how the lawyers quibbled over disparate wording when they kept asking the court clerk to read back a question they themselves had asked less than a minute earlier.

One of the crucial points was whether Lizzie really went up to the barn. Officer Medley testified that when he visited the loft there were no footprints in the dust, and it was so stifling hot that no one could have remained there more than a couple of minutes. Clearly, he felt, no one had gone to the loft, much less sat there for twenty minutes looking for sinkers and eating pears.

But George found Hyman Lubinsky, an ice cream man, who said he saw a lady walk from the Borden's barn to the house around 11:00. He didn't say it was Lizzie for sure, but it was not, he said, Bridget (who he knew). So this did corroborate Lizzie went outside. Hyman was an almost perfect defense witness. He not only supported their case, but he was also almost impossible for the prosecutors to cross-examine since he could barely speak English.

Of course, Lizzie's going to the barn could easily have been the well-known trick for establishing an alibi. After you commit a crime, the best thing to do is go someplace else, hoping you'll be seen and that the timing will be too approximate so you can muddy the waters before the jury. Or since you could get water in the barn, that may have been simply where Lizzie cleaned up.

Next George produced evidence that some handymen had been working in the barn a week before the murders. So why didn't William see their footprints? That question, along with Hyman's statement, cast further doubt on William's testimony.

George finally produced two important but really oddball witnesses, a couple of kids who skipped out from school. Dubbed "Brownie and Me" by the press (after how one of the kids referred to themselves), they said they snuck up to the barn after the murders.

And guess what? It was not, stifling hot, after all. Instead it was nice and cool - just perfect for sitting down and eating some pears. It's natural to suspect that the kids had been coached, but actually, their statements may not be so ridiculous. The construction of farm barns and outbuildings - usually a single large room - keeps them from heating up too much. As anyone who has been to a farm on a sweltering August day can attest, a trip into a barn is very often a nice respite from the heat.

So who was telling the truth, William or Brownie and Me? The testimony about the footprints is contradictory, and can't reasily be resolved. At the same time the fact that the footprints of the workmen from the earlier visit were not visible means footprints simply might not have shown on what was probably a rough wooden floor. As far as the too hot / just right testimony, with all the cops coming and going the doors could have been kept open long enough to allow the barn to ventilate from the ground floor and up through the loft. So by the time Brownie and Me showed up, the barn very well may have been cool. Still, being able to rationalize variant testimony doesn't change the fact that a prosecutor's clay pigeon, if not shot down, then was at least hit in the wing.

But when you get down to it, though, it may have been the judges that did the trick. Lizzie's trial lasted fourteen days and was tried before the jury and a panel of three - count 'em - three judges. The learned magistrates excluded the testimony of Eli, Frank, and Frederick that Lizzie tried to buy poison. They also kept out of the trial Lizzie's own confused and jumbled inquest testimony, ruling that she had not been warned of her constitutional right to remain silent - sort of a 19th century Miranda ruling.Finally there were the usual long-winded summations of the attorneys and three long-winded sets of instructions from the judges. The latter speeches were so much in Lizzie's favor that they were almost an order to ignore any incriminating evidence and to acquit.

The jury retired. After deliberating an hour, they returned with a verdict. It was "Not guilty".

Then they all went out and had a beer.

The Odds Against Lizzie

Lizzie Borden lived long and well

With Pa's money, life was swell.

But even now the topic's hot.

Did she do it? Or did she not?

One of the earliest Lizzie scholars claimed that there were thousands of divorces caused by couples arguing over whether Lizzie was innocent or not. Maybe. But even today when you would think people might be more disinterested, you can still get into some pretty fractious debates where innuendo of personality and parentage are flung back and forth.

It's really no mystery why people keep arguing about Lizzie. Americans like to believe their judicial system is virtually infallible. But you have the pesky little problem that when taken in its entirety the evidence for Lizzie's guilt is overwhelming. So you end up with a lot of arguments and a lot of books.

The books tend to flip flop over time. This is largely the result of the "I-know-something-you-don't-know" phenomenon or equivalently the "I'm-an-assistant-professor-and-I-gotta-get-tenure" bit. If the last book said Lizzie was guilty, then you want to come out with a book that says she was innocent. That means you're a sharp cookie who's figured out that all the experts before you were dunderheads. Of course, then some new assistant professorial type will come along to write a book that says once more that Lizzie was guilty and so prove you're the dunderhead. But when you get down to it, there's really been no new information beyond what there was in 1893.

So why did Lizzie get off? If standards of American jurisprudence are accepted - or at least the standards before American Presidents began imprisoning US citizens without trial - then a criminal conviction requires evidence beyond a reasonable doubt. So doubt is all that's required for acquittal - not innocence.

A lot of the doubt in Lizzie's case was due to odds that are actually true today. Murder is almost always a masculine pursuit, and men account for about 85 % of all homicides. That's today. In Lizzie's time, women caused even less mayhem - or so the statistics said.

And to quote Shakespeare, it was not so much the matter as the manner that the jury didn't like. When ladies kill, they use less blatant methods. Poison or a quick shot with a pistol is preferred, not flailing about with hatches or axes.

Juries, too, sometimes vote in a way that contradicts the totality of the evidence. The legal experts (particularly prosecutors who have just lost a case) like to talk about the "Wells Effect". This is the rule that states that if a jury can imagine a scenario where the defendant is innocent, then they will pass over massive and even conclusive circumstantial evidence in favor of acquittal. So if you're sitting on a jury and allow your imagination to wander, maybe you can picture a killer sneaking into a house, doing in the stepmother, hiding for an hour and a half in a closet, and then coming out and smacking the father before sneaking off.

Well, it could happen.

Above all, juries simply like to acquit. Not to be just nice guys or gals, but because when you find yourself on a jury you end up thinking like Maimonides (whoever he was) that it's far better that a thousand of the guilty to go free than to convict a single innocent. Sentiment, by the way, that today not everyone buys.

In the end you had a brutal double hatchet murder and a defendant who - certainly in one case - had only fifteen minutes to carve up the victim, clean up, and dispose of the murder weapon. Yes, it could be done (and probably was), but did the tight timing and clean suspect provide the reasonable doubt that mandates a jury acquit in a criminal case? Lizzie's jury evidently thought so.

So the argument in Lizzie's favor ultimately boils down to the time. She couldn't, say Lizzie advocates, have done it without getting splattered. And she just didn't have the time to clean up.

QED.

On the other hand someone was able to do it. Andrew was alive at 10:55 and dead at 11:10. If Lizzie didn't have time to clean up, then someone else must have killed Andrew and immediately spent some time just before lunch walking down the streets of a major Massachusetts city besmeared in gore. On the other hand if an unknown assailant could clean up so as to blend in with the worthy citizens of Fall River, then Lizzie could have had the time as well.

The legal eagles typically think Lizzie was guilty. That's because lawyerly types prefer a verdict based on circumstantial evidence, which they say is far, far more reliable than lousy eyewitness accounts or pidly first person confessions. In fact, prosecutors go apoplectic when lay persons (ergo, anyone who disagrees with a lawyer) dismiss evidence as merely (ptui) "circumstantial".

The reasoning for this is in the math. Although individually a single instance of circumstantial evidence may not prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, taken together several bits do. For instance, if each bit of CE (circumstantial evidence) proves guilt with a 60 % probability - plenty of reasonable doubt here - then seven bits of independent circumstantial evidence taken together will prove guilt with more than 99 % probability. Just ask a mathematician.

So what is the evidence that Lizzie was guilty? Here's the top ten reasons. Now we could assign tentative probabilties and using the appropriate theorems come up with a final likelihood that Lizzie was guilty. Unfortuntely the real calculations would require determinations of conditional probabilities or oversimplifying things by treating all odds as if they were independent. If you do the latter you'll find yourself being able to prove she was both innocent and guilty using the same information. And since that is exactly what your trial lawyers would do, we will not sink to such a level. Besides, there was once some fancy pants study that tried to calculate odds of guilt of a defendant from a hypothetical town of three - count 'em - three people. And the experts still screwed up!

In an effort to be fair, we'll skip two somewhat obvious points often cited. For one thing, Lizzie was never called to testify in her own behalf. Even in the nineteenth century (and with legal wisdom that continues today), a lawyer will only put their clients on the stand if they think they are innocent. But if they're guilty, the rule is keep 'em off. Still, it's been ruled that refusal to testify on your own behalf is not to be considered evidence of guilt. So we won't.

We'll also skip the point about the burned dress. Oddly

enough, this isn't as important as it is often thought. Yes, it could

have been the dress she wore and was burning it to get rid of it. And it is suspicous. But there

is more incriminating evidence available, so we'll just list the remaining top ten reasons why

Lizzie did it

and

let it go at that.

and

let it go at that.

1. First, Lizzie had the motive. Friends heard her say she was afraid she'd get nothing from her dad when he died, that is, everything would go to Abby. But if Andrew died without a will and Abby went too, then all the dough would go to Lizzie and Emma. And Andrew was loaded.

2. Lizzie tried to buy a deadly poison the day before her parents were killed, and denied it despite the contrary testimony of three witnesses. Very suspicious behavior.

3. Lizzie kept changing her story about the trip to the barn and the noises she either heard or didn't hear and where she was in the house at the various times. Now a few of these could be taken as simple discrepancies between statements made in a time of stress. But the contradictions were bad enough that her lawyers wanted what she said kept out of the trial. Were these contradictions due to a rattled (and doped up) young lady or the deliberate lies of a cold blooded killer?

4. Bridget, Alice, and Adelaide clearly worried the killer might still be lurking in the house. Bridget even refused to go upstairs by herself. Yet Lizzie had no worries about hidden killers. She even sent both Bridget and Alice out on errands leaving her alone without the slightest hesitation.

Why was Lizzie so at ease in a home where even her attorneys claimed a killer was still lurking? Simple - she knew the killer was not lurking anywhere, but was in the kitchen talking to Bridget, Alice, and everyone else.

5. Lizzie seemed to have a strange ability to know what had happened. She "was afraid" Mrs. Borden had been killed too. She then asked Bridget to go upstairs and see. And by golly, that's just where (the deceased) Mrs. Borden was.

That Abby had also been killed never occurred to anyone else. The most reasonable explanation why Lizzie was "afraid" Mrs. Borden had been killed was imply because she knew Mrs. Borden had been killed - and by whom.

6. Despite some minor theatrics, Lizzie showed no grief, remorse, or concern that her parents had been killed. In fact, she couldn't have cared less.

Lack of grief is a big factor in cops picking out suspects in a murder case, especially when it involves friends and family. Likelihood she was innocent? We can probably cut Lizzie some slack here, but Lizzie's calmness is definitely susicions.

7. The timing. Abby was killed between 9:00 and 9:30. So her killer was either the one person known to be in the house the whole time or it was a killer that no one saw arrive, who could enter a house that was always locked, kill a two hundred pound person so quietly a stepdaughter ironing downstairs didn't hear it, hide in the hall closet for an hour and a half (the scenario of Lizzie's lawyers), kill a second person just after the maid went upstairs and the daughter went to the barn, and then leave unnoticed by the neighbors. As Eliza Doolittle said, "Not bloody likely!"

8. Lizzie tried to set up the idea with friends and neighbors that Andrew had enemies that wanted to do him in. She said as much to Alice the night before. Later she kept this story up and even claimed the killer was her not-so-beloved uncle, Hiram Harrington, who didn't like Andrew.

Now it is true that there were people who didn't like Andrew, both personally and professionally. But it looks for the world like Lizzie was already working on an alibi.

9. Then there's the story of the note. The note was one of the most publicized items of the case. Everyone in town knew about it. But no one ever came forward, not even after Lizzie and Emma put ads in the papers.

So what are the odds that someone would have sent the note and not come forward? Oh, yes, you can invent explanations. Maybe it was from a recluse who never read the papers. Perhaps the note sender didn't like Lizzie and wanted to get her unjustly convicted. Maybe the sender left on a trip to a health spa in Dusseldorf just after Abby left her house. Maybe it was an early case of alien abduction.

Despite any imagined scenarios, the actual odds of there being no note are still very high - in fact, it's close to a certainty. Remember, Lizzie said Abby went out because she got a note. But Abby never went anywhere. Lizzie said she heard Abby come back in. But by that time Abby had been dead for two hours.

At this point we should mention there have been fairly recent arguments that Abby was actually killed after Andrew - saying the forensic guidelines for the times of death are not correct. As dicussed in the footnotes, these arguments are simply reverse engineering in the manner of a defense attorney. Yes, there can be exceptions to general guidelines, but it is extremely unlikely that all the forensic guidelines will be violated in a single case. But more to the point, such arguments contradict the greatest single point against Lizzie - which brings us to our final and most conclusive point as to why Lizzie was guilty.

10. No one - that's no one saw Abby after 9:00 - not in the house, not on the streets, not anywhere else. But everyone else in the family was practically on display for every citizen of Fall River. Andrew was seen by enough people so his whereabout are known almost by the minute from the time he left home to the time he got back (even his having trouble with the lock was seen by a neighbor). Bridget was seen running down the street after Lizzie sent her out, saying she couldn't be left alone. Even Lizzie was noticed as she walked out the back of the house to the barn. If you stepped outside that day, someone would see you. But let's say it again and out loud - no one saw Abby after 9:00. If she had gone out someone, somewhere, would have seen her and said so. So we can be confident - well beyond a reasonable doubt - that Abby did not - that's she did not - leave the house to visit a sick friend as Lizzie said.

But Lizzie said Abby got a note and left the house. Lizzie also said she heard Abby come back in. But let's say it once more - and pardon us if we shout NO ONE SAW ABBY AFTER 9:00 AND THEY CERTAINLY WOULD HAVE IF SHE HAD LEFT THE HOUSE!

So Lizzie was deliberately lying, and we have to conclude Lizzie was guilty.

Although putting quantitative numbers on Lizzie's guilt isn't easy, all in all and taking everything into consideration we have to conclude either no one killed Abby and Andrew or Lizzie did. And we certainly know that someone did.

Lizzie's Legacy

Did Lizzie Borden of Fall River,

Do that crime that makes us shiver?

Though she got off and did no time,

All we remember is the rhyme.

When Lizzie was acquitted, the newspapers praised the verdict. The evidence had been presented, the judges had made their rulings, and finally the jury had spoken.

But the accolades for American Law and Lizzie quickly petered out. Soon young girls around the country - the world even - were skipping rope to the now famous refrain.

Lizzie Borden took an axe

And gave her mother forty whacks.

When she saw what she had done.

She gave her father forty-one.

It's probably not a great tribute to the educational system of America that a jump rope rhyme soon made people forget the outcome of the trial of the (nineteenth) century. Within fifty years, most people were surprised to learn that Lizzie got off scot free. Even now with more books about Lizzie selling better than many biographies about American presidents (certainly Warren Harding's), odds are the average Joe Blow on the street will think Lizzie got convicted.

Would Lizzie have been convicted today? Again if you believe what the law journals say about juries tossing out good (even conclusive) circumstantial evidence and if Lizzie could get her high priced lawyer, about all we can say is maybe; maybe not.

But when you get down to it, Lizzie was also lucky as heck. If Bridget had stayed downstairs when Andrew came home, then only half of Lizzie's plan could have completed. Andrew or Bridget would eventually have stumbled on Abby. With Andrew alive and Abby dead, the whole Papa-Had-An-Enemy alibi would go down the tube. Then you're simply left with a daughter who killed her stepmother, a stepmother who she didn't like. Even an all-male Victorian jury would have believed that.

Lizzie stayed in Fall River but moved with Emma to a new house they rather ostentatiously named "Maplecroft". It was bought, of course, with their dad's money. But with the Lizzie-took-an-axe rhyme being sung on the sidewalks and in the school yards, Lizzie rarely ventured out into the streets of her hometown. Instead, she spent a lot of time traveling to Boston, New York, or Washington where she could walk around, go the theater and art galleries, and not be recognized. Soon she became rather bitter that people kept thinking she killed her folks. After all, she said, she had been acquitted, and besides, it was really her uncle, Hiram Harrington who had done the whacking.

With her dad and mom out of the way and big bucks in her pockets, Lizzie could finally make friends the likes of which her folks would never have approved. Mostly she began to hang around the theater and artsy crowd. There's even speculation she had a - well, a "relationship" with the well-known actress Nance O'Neil. As with much Lizzie theory there's little real evidence for this other than the two women were friends and spent time together. But in 1904 and after Lizzie and Nance met, the prim and proper Emma moved away from Lizzie and went to New Hampshire. She never, as far as we know, spoke or wrote to Lizzie again. But Emma did take her share of the money.

Lizzie died at her home in Fall River on July 1, 1927. She was just shy of her sixty-seventh birthday. The same day the seventy-six year old Emma slipped and fell in her home in New Hampshire. She didn't recover from the accident and died on July 10, just nine days after Lizzie. The two sisters had a total of $675,000 left from what they got from their dad, showing us just how well set up Andrew had been. $450,000 of it was Emma's and Lizzie, obviously the big spender, only had a measly $225,000.

The Borden home is still there in Fall River, and it's now open to where you can make reservations to spend the night. All the rooms are available: Abby's and Andrew's, Emma's, Bridget's, and Lizzie's.

Oh, yes - you can even sleep in the guest room - where Abby was killed.

We hope you have a nice LOOOOOOONNNNNNNNGGGGGGG sleep.

References and Bibliography

The source of this Merry History was mainly the primary documents of the case - police statements and the inquest and trial transcripts - which all make a heck of a lot more interesting reading than the plethora of Lizzie books. Electronic copies have been made available by Dr. Stefani Koorey and her friends of the Lizzie Borden Society, and so we have here a modern miracle - a fully reliable internet resource which lets people make up their own minds.

For Lizziephiles, the sources to check are:

"The Trial Of Lizzie Borden", Edmund Pearson, (Notable Trials Library, private printing). A 1989 reprint of the 1937 original. Excellent quality and the most accessible volume for actual trial testimony although some is given in summary and paraphrase. Lizzie fans should have this volume. It not only gives much verbatim testimony on every day of the trial but also the lawyers opening statements, various motions, and closing arguments. Boy, those barristers are a windy bunch.

In reading inquest and trial testimony everyone should remember that 1) the vast majority of witnesses are telling the truth as best as they can, 2) the earliest testimony is the most accurate, memories fade, and contradictions in testimony are to be expected, 3) accepting circumstantial evidence will lead to more correct verdicts that using direct evidence, and 4) the attorneys are trying to win their case, not establish the truth.

Edmund believed without doubt that Lizzie was guilty and the judges were biased in her favor. He does get a bit preachy in his introduction, though.

"LizzieAndrewBorden.com". This is Stefani's site and is at

http://www.lizzieandrewborden.com/LizzieABorden.htm

One document is particularly valuable for Lizzie sleuths and that's the police witness statements, listed in order of the day they were given. These give us what the people said right after the murders, untainted by any hindsight or influence from what others said - not to mention trying to protect their rear ends. The statements paint a picture of a time of confusion, but also of a reasonably competent police department chasing down all possible leads, but still a nineteenth century police department where the officers did not receive what we would consider proper investigational training. There's also the inquest testimony, which along with the police statements, are the most accurate renderings of Lizzie's own words. You also have a full trial transcript where Lizzie only said she was innocent and her attorney would speak for her.

Stefani's site also gives us articles, essays, and chronologies. There are even (bleah) the crime scene photos and (double bleah) autopsy reports.

Bravo to Stefani for making so much objective and primary information available to anyone - and it doesn't cost you a penny.

Stefani also is editor of "The Hatchet" a perfectly serious journal of Lizzie studies. As "The Hatchet" is a bonafide magazine there is a subscription cost. More information can be found at http://www.hatchetonline.com/HatchetOnline/index.htm but you can also access the site through http://www.lizzieandrewborden.com which is the generalized web site for the Lizzie Borden Society.

"A Fresh Look at the Character of Andrew Borden", Denise Noe, The Hatchet, May, 2006. This article argues that Andrew's character has been unjustly maligned. Andrew was not a lavish spender, certainly, but maintaining he was a millionaire miser who wouldn't pay for his wife's doctor's bills is not the full picture.

First, the article makes it clear that some statements by other authors about how tight Andrew was are absolutely false. One of the Andy-was-cheap authors claimed he had removed all running water from the house and so forced more drudgery on the girls. But the truth is that Andy put in running water as early as 1874, and it was never taken out. He had also hired Bridget as a full-time live-in maid, and Abby and Bridget seem to have taken on the lion's share of the housework. Other than taking care of their own rooms, Lizzie and Emma really had little to do.

Andrew also let his daughters take extended vacations (as a young lady Lizzie even made a tour of Europe), and he gave them a quite reasonable monthly allowance. Within that allotment then, the girls led their lives pretty much as they wished. Yes, Andrew was careful with his money, but he was not always a tightwad in any absolute sense.

But (and there's always a "but"), this doesn't mean that Lizzie was satisfied with her lot. Contemporary statements by those who knew her make it clear that Lizzie thought her dad was miserly and that she, a well-to-do young lady, should have more of a social presence in Fall River. It doesn't matter if Andrew was or was not a tightwad. Lizzie thought he was.

All this really is beside the point because Lizzie didn't chop up her dad because he was a tightwad. She did it because she worried that Andrew would cut her out of her will, a worry supported by contemporary statements.

Was Andrew going to cut Lizzie out of his will? Almost certainly he was not. Yes, Andrew gave property to Abby's family, but he also gave property to Lizzie and Emma. And when they found being landladies took too much work, Andrew bought it back at a then quite reasonable payment. He was looking after the girls (or at least trying to address their worries) and someone like that would probably not cut them off.

"Lizzie Borden Unlocked", Ed Sams, (Yellow Tulip Press, 1995). A short book but a good telling of the case and not bad for it's price. Particularly since you can read the whole text free at http://www.curiouschapbooks.com/cntnts.html.

"Famous Trials", by Douglas Linder, Professor of Law at the University of Missouri, Kansas City, Law School. An excellent website of (what else?) famous trials:

http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/ftrials.htm

This is another internet site that can be referenced along with actual printed material - the primary source material (usually trial and inquest testimony and newspaper accounts) is included. Lizzie's trial is at

http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/LizzieBorden/bordenhome.html

Professor Linder thinks Lizziedunit.

"Lizzie Borden", Russell Auito, The Crime Library at http://www.crimelibrary.com/notorious_murders/famous/borden/index_1.html

The Crime Library was once a great site until Court TV bought it out and with the poorly redesigned format, multiple ads, and pay-to-view stories completely ruined it. Lizzie's story covers the basics and gives pro- and anti- Lizzie arguments. Most credibility is given to "Lizzie did it" scenarios.

"What Made Lizzie Borden Kill?", Marcia Carlisle, American Heritage Magazine, June/July, 1992. The savagery of Lizzie whacking away at her parents still raises eyebrows, and this article suggests that the reason was that Lizzie (and Emma) were abused by Andrew. So there's now the "Did-he-or-didn't-he" question regarding Andrew.

It is possible, of course. But as the article does point out, patricide in abuse cases is extremely rare. Furthermore attempting to deduce the course of events by use of psychological reasoning alone can be extremely hazardous to the facts.

The difficulty is that what are often seen as clues of an abusive relationship are on the surface quite innocuous and are also characteristics found in normal, happy, and non-abusive families. For instance one hot-shot psychologist noticed that abused children played with dolls in a certain way. It was thought that this observation could then be used to identify abused children until proper controls were run. Then it was found many non-abused children acted the same way.

In trying to reconstruct Lizzie's psychological profile you can invent many scenarios, all of which fit the facts. For instance, some alternative explanations for the Lizzie's modus might be:

It's known that Lizzie was an animal lover, and a few months earlier her dad had killed her pigeons. Neighborhood boys were hunting the birds, and to keep the kids from breaking into the barn, Andrew chopped off the birds' heads. So you have the theory that her anger at her father pushed her over the top and on to taking the drastic action regarding her concerns about her inheritance. Lizzie may have seen her choice of weapons as making the punishment fit the crime once her original poison plan was thwarted.

Alternatively Lizzie may simply have seen her method as keeping in with her story that Andrew's enemies did him in. Dispatching Andrew so savagely via hatchet can be - and was - an argument against the killer being a woman. But it could very well be used as an argument that some angry client from his bank or rentals decided to settle a difference permanently.