Jean-Paul and Simone

What does it all mean?

Jean-Paul and Simone

OK. Which of these quotes is NOT bonafide Jean-Paul Sartre?

| Freedom is what you do with what's been done to you. |

| Nothingness lies coiled in the heart of being. |

| The appearance of the other in the world corresponds to a congealed sliding of the whole universe. |

| Awe is but the product of an uncomprehending mind. |

You'll read on the Fount of All Knowledge that Jean-Paul Sartre first heard of existentialism in 1941. And when he did he disavowed the philosophy. But he soon changed his mind and gave his famous lecture, L'Existentialisme est un Humanisme, or as usually translated for us English speakers, Existentialism and Humanism. Then, hey, presto!, there were existentialists sitting in the cafes along banks of the Seine.

Actually the word goes back at least to 1922. Edward Titchener, a pioneering experimental psychologists, said in an article in the American Journal of Psychology, the goal of his research was "somehow to bring intentionalism and existentialism together at close quarters." Which makes about as much sense as some of the things Jean-Paul said. But Edward was referring to the then current theory of psychology called structuralism. We won't drift off into yet another field with even more terms you need to define, so we'll pass on.

But in philosophy, we find that existentialism was used as early as 1933. This was when Arthur Lieber wrote in the Philosophical Review that existentialism was "a philosophy which makes being its starting-point." As we'll see, this is itself a good starting point for the word.

But, yes, it was in 1941 that Julius Kraft, a German sociologist, used the word as we know it today. This was in an article in Philosophy and Phenomenological Research where he pooh-poohed the idea that existentialism, the "philosophy of existence" was anything new. The paper drew a response from the American philosopher Marvin Farber which drew a response to the response from Julius.

But enough of etymology. We'd like to know just what the heck is this philosophy called existentialism.

I thought you would, as Captain Mephisto said to Sidney Brand. It's very simple really. With just minor editing we can give you some proper definitions. So we learn:

Existentialism is a philosophy that emphasizes the uniqueness and isolation of the individual experience in a hostile or indifferent universe, regards human existence as unexplainable, and stresses freedom of choice and responsibility for the consequences of one's acts. [American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language]

Or maybe you learn that existentialism is:

A chiefly 20th century philosophical movement embracing diverse doctrines but centering on analysis of individual existence in an unfathomable universe and the plight of the individual who must assume ultimate responsibility for acts of free will without any certain knowledge of what is right or wrong or good or bad. [Merriam-Webster's Dictionary]

Or perhaps:

A system of ideas in which the world has no meaning and each person is alone and completely responsible for their own actions, by which they make their own character [Cambridge Dictionary].

And even:

By the mid 1970s the cultural image of existentialism had become a cliché, parodized in countless books and films by Woody Allen. [Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy]

And ...

You know what Sartre told me at dinner last night? That a newspaperman made up the word "existentialism" and that he, Sartre, had nothing to do with it. [Ernest Hemingway in conversation with A. E. Hotchner, 1948]

Now what makes defining existentialism so tough is it quickly became de rigueur for existentialists to deny they were existentialists. So people who were existentialists were saying their philosophy wasn't existentialism. Then to confuse things more the earliest existentialists existed before existentialism existed and so the existence of existentialism existed before the existence of existentialism!

Try saying that fast six times.

One thing we do know. Most historians say the famous Danish philosopher, Søren Kierkegaard, was the first existentialist. And of course, like a good existentialist, Søren never claimed to be an existentialist. In fact, he never heard the word.

Then there's Friedrich Nietzsche. A one-time friend of Richard Wagner, Friedrich is also labeled an existentialist. Friedrich, of course, is most famous for his "God is dead" philosophy and advocating the concept of the übermensch. But he, too, had never heard of existentialism.

But you may prefer to say the first real existentialist philosopher - or at least an existentialist who lived long enough to deny he was an existentialist - is the German professor, Martin Heidegger. Martin is either considered one of the greatest philosophers of the 20th century or a flat out charlatanistic racist, windbag, and salaud. Certainly it didn't help that during the 1930's and 40's he became an enthusiastic supporter of National Socialism.

But it's the emergence of Jean-Paul Sartre in the late 1930's that led to the philosophy we can clearly call existentialism. Of course, Jean-Paul wrote in French, and so he used the world existentialisme and by 1946, he was definitely calling himself an existentialiste.

You see the problem. If you're an existentialist you can be an insecure Christian (Søren), a crazy atheist (Frederich), a dedicated Nazi (Martin), and of course, you can be Jean-Paul Sartre.

Today there's even a debate if existentialism is really a philosophy at all. Instead it seems more of a cultural and artistic movement centered around Paris during and after the Second World War. However, nationality and locale doesn't really matter. So belatedly we end up hearing that existentialists number people like Irish playwright Samuel Beckett, African American novelist James Baldwin, Dutch-American abstract painter Willem de Kooning, and German psychiatrist Karl Jaspers (who was a buddy of Martin Heidigger). And a lot more.

There is an easy way out of our definitional dilemma, though. We take a lesson from country music. After all if you want to define bluegrass you simply say it's the type of music that Bill Monroe played. Then you know that if someone plays music like Bill Monroe, they're a bluegrass musician.

So if you're talking existentialism, you're talking Jean-Paul Sartre. And if someone's philosophy is like Jean-Paul's, then they're existentialists.

OK. Just what is Jean-Paul's philosophy - that is, existentialism?

The fundamental tenet of existentialism was stated by Jean-Paul in that famous talk Existentialism and Humanity. There he said:

Existence Precedes Essence!

... which at first doesn't really seem to clear things up.

To understand what Jean-Paul meant you have to understand what essence is from a philosophical standpoint. The essence of something is the smallest set of properties which gives something it's identity. That is, individual items - like a bunch of tables - may vary in certain characteristics: color, size, shape, and material. But all share some common properties that make them recognizable as a table. These common properties are the essence of the objects.

Philosophers like Aristotle thought essence was real - even if no specific items with that essence yet existed. For instance, we recognize the essence of our tables whether we have made a specific table or not. To create a table, we must already be aware of its essence. Or as Aristotle would have put it, the essence of something must precede its existence.

But Jean-Paul said no. That's not true. Things exist first. Then we determine what makes it what it is - that is, its essence. Essence, then, is also invented by people but after the things exist.

In other words, Jean-Paul said existence precedes essence. And this principle applies to everything. Inanimate objects, living beings, and even philosophy and moral codes.

Therefore, Jean-Paul said, there are no abstract principles to live by. Morality is an essence, yes, but one created by the existence of the individual and his culture.

But that doesn't mean that there is no such thing as free will, said Jean-Paul. People do have free will and with free will comes responsibility. But the free will and responsibility are not directed by some underlying morality independent of the individual. In fact, people who believe in higher moral codes are actually avoiding responsibility since they will be moral only as long as someone else tells them what to do.

In a nutshell, then, existentialism is a philosophy that the world is a crazy place with no coherent meaning. On the other hand, people do have free will and so are responsible for their actions. If such responsibility causes you anxiety, well, as the existentialists say, that's just tough tiddy.

Jean-Paul was born in 1905 in Paris. His dad, Jean-Baptiste, died when Jean-Paul was only two. So it fell to his mom, Anne-Marie to raise him (hyphenated first names seemed to be favored among the Sartes). Anne-Marie, by the way was also the first cousin of the famous missionary Albert Schweitzer.

Jean-Paul found it hard to fit in with other kids, and when his mom remarried he never got along that well with his step-dad. So for solace he turned to reading.

By the time he graduated from high school, Jean-Paul had a love of books, an exotropic strabismus, and looks even he didn't call handsome. So he decided to be a writer. Of course, he also had to eat and he thought being a teacher was a good way to earn some francs. So he enrolled at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris.

You'll read on the Fount of All Knowledge that Jean-Paul got a Ph. D. and then went to study philosophy with Martin Heidegger in Germany. This is true and false. Yes, Jean-Paul later studied in Germany but not with Martin. Nor did he get a Ph. D. He was awarded what is called the agrégation. This is a diploma granted by the French government that lets you teach both in high schools and in universities. It's quite prestigious and only about 10 % of the applicants get the agrégation. Jean-Paul had to try twice.

Strictly speaking, Jean-Paul could have looked for a college post. But then as now there are more high school jobs available. So after first spending 18 months in the army, Jean-Paul became a high school - or lycée - teacher. During the 1930's he taught at Le Havre and in Lyon.

After a year or so of teaching high school kids, Jean-Paul needed a break. But more and more he had become serious, not just about writing, but about philosophy. So he applied for a government grant to study at the French Institute in Berlin. There he read the papers and books of the German philosophers. However Jean-Paul didn't actually meet Martin until after World War II.

These studies not only gave him a respite from dealing with kids, but also a boot up in the official philosophical circles. So he returned to teaching and started writing mit gern.

Exactly when his first book was published varies with your source. The reliability of the Fount of All Knowledge seems dubious and one data base gives a publication date of L'Imaginaire (The Psychology of Imagination) as 1907. It's unlikely, though, that Jean-Paul was publishing philosophy when he was only two years old. One of the most popular informational website lists the date as 1940.

However, Diligent CooperToons Research found the date was actually 1936. This also agrees with the date listed in a standard encyclopedia written by actual experts rather than by the general public whose sources are usually other websites which sometimes just reference each other.

The confusion of when L'Imaginaire hit the bookstands seems to arise because the first imprimatur was from a small Parisian printer (remember Jean-Paul was an unknown high school teacher when he got back from Germany). This was the 1936 edition. Then later Jean-Paul had begun making a name for himself and a more mainstream publisher put out their own - quote "first edition" - unquote. That was in 1940.

Books on philosophy, though, rarely make you famous - or rich. So in 1938, Jean-Paul tried his hand at fiction. Reading novels back then was the equivalent of watching television, and successful writers could gain the standing that film, sports, or rock stars have today. The novel, La Nausée (Nausea) sold well, was soon followed by a book of short stories, Le Mur, (The Wall). Jean-Paul was suddenly not only a philosopher but a celebrity.

Alas, he also found himself fighting the Germans. In 1939, Hitler invaded Poland, and in keeping with a prior agreement, France joined Britain in the war against Fascism. Jean-Paul was drafted into the army and found himself helping forecast the weather. But France quickly lost the battle and the war. They then surrendered to the Germans and blamed Britain for the whole bloody mess.

In the resulting treaty it was agreed Germany could occupy the north part of France - including Paris. But as a concession, there would be a second - quote - "independent" - unquote - French government based at Vichy in the south. The man officially running things was France's World War I hero, General Philippe Pétain. But everyone knew the Germans were really in charge. Charles de Gaulle, leading what was called the "Free French" government, was so disgusted at what he saw as a sell-out that he urged his countrymen to rise up and fight the Germans. Of course, that was easy for le gran Charlot to say since he had high-tailed it to Britain.

But the average soldier wasn't so lucky, and Jean-Paul found himself in a POW camp. But like another famous philosopher, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Jean-Paul found that wartime imprisonment was great for philosophy. So with nothing else to do he ended up writing another book, L'Être et le néant (Being and Nothingness). Still cited as his most important work, the book was published in 1943, two years after Jean Paul was released. He returned to teaching high school - this time in Paris.

The Germans loved Paris, and it became a major center for military R-and-R. Although Hitler had declared jazz age entertainment as degenerate art, places like the Hot Club de France with its star guitarist, Django Reinhardt, remained open. Django was of gypsy ancestry and would have been subject to deportation to a concentration camp except that one of the German officers, Dietrich Schulz-Köhn, was not only a jazz fan, but a bonafide expert. And despite rationing and shortages, cafe life continued.

Of course, in the pre-television days, reading magazines and books were not the only mode of passive entertainment. Films had been a big industry for about twenty years. But like today, attending plays was always good for a night out and also added a certain intellectual air to your activity.

So Jean-Paul the novelist, philosopher, and high school teacher became Jean-Paul the playwright. His first play, Les Mouches (The Flies), is said to have - and here we quote still one more popular informational website - "a blatant anti-Nazi message". It is strange, though, that the German censors could be handed a play with - quote - "a blatant anti-Nazi message" - unquote - and see nothing nothing blatant or even objectionable. It was approved for performance.

The play is, in fact, a retelling of the Euripides's play Electra. Like the original, Jean-Paul's play is set in Ancient Greece, the main characters being Zeus, Electra, and Orestes. If the German censors saw nothing objectionable, neither did the German officers attending the opening. But overall the reviews weren't very good.

Jean-Paul's next play, Huis Clos, usually translated as No Exit, fared better. Again the Germans saw nothing amiss and the play was performed a few months before Paris was liberated by the Allies.

Instead it was the English censors who objected to the play. Or at least they didn't approve of the - ah - "preference" exhibited by Inez toward Estelle. The play was banned in Britain. Also Pope Piux XII didn't care for the play and slapped it on the Index of books that Catholics were forbidden to read. In fact, all of Jean-Paul's books were eventually banned by the Church.

No Exit is the first existentialist play and a combination of it being a good play, needing only four actors, and requiring minimal stage props has assured it remains one of the most performed plays today. In the US alone there have been no less than three recent productions in New York, three in Ohio, two in North Carolina, two in California, and other performances scattered through DC, Massachusetts, Mississippi, Nebraska, Illinois, Kentucky, Kansas, Louisiana, and Montana. The play has also recently been staged in England, France, India, and Egypt.

No Exit - or rather Huis Clos - was also made into a motion picture in 1954 with other movies and television remakes following as late as 2014. In a personal CooperToons opinion, the first film - which is in French - is the best. Since No Exit is one of those plays that you can only appreciate if you don't know the plot, we won't say any more.

After the war, Jean-Paul found himself an internationally famous philosopher, novelist, and playwright. So there was no longer any need for him to teach high school. He could now spend the rest of his life writing, lecturing, traveling the world, and hanging around with his friends. A good job if you can get it.

It also was after the war that everyone learned that while maintaining the cover of a harmless philosopher, Jean-Paul had been writing articles for underground anti-German newspapers. This itself was a hazardous occupation since it was always possible that informers could identify the people in the distribution network and trace them back to Jean-Paul. He was now hailed as a member of the French Resistance.

Still, with today's gotcha journalism some writers have found that Jean-Paul's having two plays approved by the wartime Germans brings his actual wartime activities into question. Just how much of a resister could he have been?

There are even some people - including the Minister of Culture under De Gaulle, André Malraux - who snorted that Jean-Paul was no better than a collaborator. I mean, the German officers not only attended Jean-Paul's plays in front-row seats but also stopped in for the cast parties afterwards! Resístance? Not, as Eliza Doolittle said, bloody likely.

Counterpoint: You can argue that such dissembling was necessary. After all, resistance members under arrest aren't very effective. And a friend of Jean-Paul, John Gerassi, wrote that from the first, Jean-Paul had actively been a member of a resistance cell and in 1941 had even tried to get André to join. But André - according to John, a "onetime Communist sympathizer turned Gaullist mouthpiece" - was "enjoying the good life on the French Riviera" - and refused. And yet, you'll also read that André did so join the Resistance group at Jean-Paul's behest.

For his own part Jean-Paul downplayed his role in the Resistance. In later interviews he said he was apolitical and admitted at first he had actually been in favor of the anti-aggression pact between Russia and Germany. As a POW he had used his "docility" as form of resistance and was, we read, a writer who resisted rather than a resister who wrote.

Actually the writer/resister quote was not from Jean-Paul, but was from his fellow philosopher and journalist Albert Camus, who had met Jean-Paul during a production of The Flies. Albert was an active member of the French Resistance, and although he didn't engage in sabotage or shoulder arms, he did edit the Resistance newspaper, Combat. And Combat is one of the "underground" papers you'll read Jean-Paul wrote for.

Well, what's the truth? Although supposedly Jean-Paul wrote articles for Resistance papers like Combat, we know he wrote two articles for Comoedia, which was a "collaborationist" paper. Of course, his fans can say these articles, too, were smoke screens, covering up his Resistance activities. We can, of course, continue with this point-counterpoint stuff forever.

Today writings about existentialism have fallen off from it's maximized popularity of the mid-1960's. In fact, in some circles it's become popular to pooh-pooh Jean-Paul and his philosophy altogether. The reasons for such existential dismissal are 1) Jean-Paul is receding into history, 2) Jean-Paul's politics have fallen into disfavor, and 3) we've learned some rather unpleasant facts of Jean-Paul's personal life.

Although Jean-Paul lived a long life - at least for someone who kept going by popping a mix of amphetamines and aspirin washed down by daily doses of coffee, wine, and whiskey, and smoked like a chimney - he was a celebrity of his times. And no one fades from view quicker than a celebrity of his times, at least once his times are over.

And there's no doubt that Jean-Paul was politically left, and many of his think pieces are accurately called Marxist. In his essay on antisemitism Jean-Paul argues that in a true classless society - the ideal Marxist state - prejudice vanishes. He even claimed that at the present there was virtually no antisemitism among the working class.

George Orwell saw the essay as laughably naive and said so in print. Many people today agree that Jean-Paul was a bag of wind (George's words) and go into foamy mouthed diatribes about how Jean-Paul and other (ptui) liberals can go around preaching freedom while idolizing mass murderers like Joseph Stalin, Mao Tse-Tung and Che Guevara.

In 1964, Jean-Paul was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. But because he refused to be part of the establishment, he turned the prize down. Besides, he said, he never accepted awards.

It was only natural that during the 1960's - a time of tumult throughout the world - Jean-Paul was hailed by the counter-culture as a true and trusted leader. This despite him being well over thirty. In fact, in 1965, he turned sixty and an increasingly conservative French government blamed Jean-Paul for what is courteously called the "student unrest" of 1968. In one of the greatest ironies of European history, the students in Paris had gotten so much out of hand - Paris was really getting trashed - that the long time president of the Fifth Republic, Charles de Gaulle, went to Germany to seek possible military aid.

As the years rolled on, Jean-Paul became even more extreme in his politics. When there was the terrorist attack on the Israeli Olympic team in Munich in 1972, he said the attack was justified. Even terrorism, he said, was a "valuable political gesture", and in 1975, he even visted Andreas Baader, the head of the then infamous Baader-Meinhof gang in prison. Jean-Paul held that the actions of the gang - who preferred to be called the "Red Army Faction" - were "entirely justified". The gang, he said conducted themselves well. "They never killed a single innocent person," he added. "They hunted down vicious pigs within their society, and the American colonels that crawled before them."

Once more our desire for existential accuracy requires us to point out that during the hour long conversation, Jean-Paul actually told Baader that the gang's tactics were wrong - at least in France or Germany. Baader seemed perplexed that Jean-Paul dared disagree that shooting down unarmed businessmen was the way to promote freedom, and he read a three page "statement" from the gang. At times Jean-Paul would ask him to explain certain points, and Baader - clearly no philosopher - seemed confused and simply repeated the sentence or went on to the next.

Jean-Paul didn't seem to like Baader too much either and described him using a most discourteous French word. But publicly he reiterated his support of the gang. He said that the current West German government (there were two Germanies at that time) was the successor to Hitler and that the Red Army Faction was a form of the Resístance.

Public opinion turned against Jean-Paul and apparently began to hit him in the pocket book. Or at least later the same year he met Baader, someone had discretely approached the Nobel Committee asking if Jean-Paul might possibly be given the money for the prize he had turned down ten years before. Jean-Paul didn't want the prize, thank you. Just the money.

Saying Jean Paul would secretly ask for the money of a prize he publicly rejected sounds like a snit so typical of des déchets you'll read on the Fount of All Knowledge. But the source of the story is a good one. It comes from none other than, Lars Gyllensten, who was the Nobel Committee member in charge of the Literature Prize. So that some representative acting on Jean-Paul's behalf asked for the dough can't be denied. But it didn't matter. The money had been returned to the Nobel fund for future prizes. Dommage, Jean-Paul, aucune acceptation, aucun argent.

Jean-Paul lived another five years. Despite the fact that he had lost considerable standing with the establishment - even the "cool" establishment - he still had his fans. When he died in Paris in 1980, 50,000 people lined the streets for his funeral.

It was as a student at the École that Jean-Paul met Simone de Beauvoir. Simone was born in 1908 to a well-to-do family that had invested most of their money in Russian stocks. The First World War and the Bolshevik Revolution took care of that and the de Beauvoirs found themselves in virtual poverty before Simone was 10.

However, the family managed to bounce back, and Simone was a good student. She, like Jean-Paul, loved books and there was no question but she would attend college.

In many ways, Simone's life mirrored Jean-Paul's. She, too, gained her agrégation and taught in high school. For some reason, Simone - who dressed fashionably and was always conscious of her appearance - took to Jean-Paul, who when described as being 5'3" is giving him a 3" credit. Jean-Paul also decided to promote environmental consciousness by not wasting water with excessive baths or brushing his teeth.

Although Simone is now considered an important existentialist philosopher, for decades she was described simply as a feminist author and was most famous for writing Le Deuxième Sexe (The Second Sex). The reason she's been neglected as a philosopher is that she tended to write in a way that that doesn't require other authors to publish multi-volume explanations about what she meant. For instance, compare the samples of Jean-Paul's - ah - "wisdom" that we posted above with some things Simone wrote:

This has always been a man's world, and none of the reasons that have been offered in explanation have seemed adequate.

Society, being codified by man, decrees that woman is inferior.

When an individual is kept in a situation of inferiority, the fact is that he does become inferior.

What is odd is that such comments by Simone can still draw vituperous rants on the Fount of All Knowledge. Despite what you read on websites with names like insecuremenventingtheirspleens.com, it's impossible to deny that the world has been crafted by and is still largely run by men. In Ancient Greece women were scarcely allowed out of the house (even men did most of the shopping). In Rome, they had no vote and had to be subject to the authority of some adult male. Even in western and ostensibly advanced countries like the United States women only gained the right to vote in the 20th century.

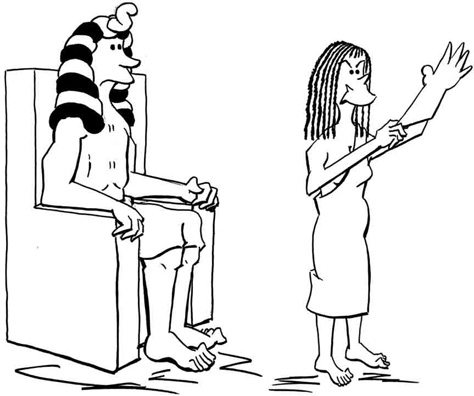

Opportunities for Women

Ironically it was in Ancient Egypt that women had most of the rights as men. True, they couldn't be priests, but they could be the "singing women" in the temples. Ancient Egyptian women could also own property, run businesses, and one lady named Peshet became physician to the Pharaoh. Some women even became kings themselves.

The Second Sex has remained in print since its publication in 1949 and an American edition was issued in 1952. Retranslations have appeared off and on, the most recent in 2010. Like Jean-Paul, Simone wrote not only think pieces, but also novels and stories. Her one play, Les Bouches Inutiles (Useless Eaters) was first performed in 1945 but has not become part of the standard repertory.

Simone and Jean-Paul quickly became what we call "a pair" and the pairing continued as long as they lived. They considered themselves bound together, but entered into no legal arrangement. They agreed both could still fiddle around but must be honest and tell the other about their fiddling.

As a teacher Simone taught in a girl's school and told her pupils that women were every bit as good as men and deserved equal rights and opportunities. The girls, for their part, were happy to have a young and intelligent woman as a teacher rather than a boring fatuous vieux schnoque who was the norm in the schools.

However, during the war Simone was dismissed from her post. The specific complaint was one of the girl's mother had complained that Simone had been corrupting her daughter. Today this incident has has been interpreted that Simone and the student had an "inappropriate relationship" if we use the words that politicians, media celebrities, football coaches, and religious leaders say when caught in similar activities. Simone got the boot and was forbidden ever to teach in the school system again.

On the other hand you can take this as a frame-up by the occupying Germans against a straight talking liberated woman who undermined the Kinder, Küche, and Kirche doctrine. Certainly it's scarcely a black mark if you get dismissed from a teaching post by the Nazis.

But it is undoubted that Simone did not have any biases regarding gender in her relationships. And as she still had her pact with Jean-Paul, she felt it was OK for her to have her other partners stop by Jean-Paul to see if they shared her tastes. On the other hand, her students continued to express admiration for Simone and Jean-Paul, and from what one them, Bianca Bienenfeld, said, no actual relationship began until after she had graduated. Bianca continued to visit with Simone long after she had married, and after the war the two women met for lunch every month until Simone died in 1986.

But Bianca's opinion of Simone changed when Simone and Jean-Paul's letters were published in 1991. Although Simone and Jean-Paul used nick-names when referring to the girls, Bianca recognized the references to herself, which were often condescending and sarcastic comments. In the end she felt that Jean-Paul and Simone saw her just as a play toy for the pleasure of iconic philosophers. That was too much and Bianca published her version of the story in 1996.

Simone's and Jean-Paul's - well, complex living arrangements - could involve not only the young women but also their husbands and boyfriends. If Simone and Jean-Paul kept up their pact to tell each other about their dalliances, then they must have had a lot to talk about.

Jean-Paul's modus copulandi has some writers wondering. Was he really living according to his existential philosophy where he was freed from some supposed but repressive code of pseudo-morality? Or was he simply another male chauvinistic porc preying on young and vulnerable women and using his philosophical spouting as a hypocritical tool to achieve his conquests?

The question is a legitimate one. Once one of Jean-Paul's friends asked him how he managed to have so many and simultaneous girlfriends.

"That's easy," Jean-Paul said. "I lie to them."

"All of them?" his friend asked.

"All of them," Jean-Paul assured him.

"Even Simone?" His friend was surprised.

"ESPECIALLY Simone," Jean-Paul responded.

True, you may prefer to say this conversation was simply an example of Jean-Paul's puckish sense of humor and his wisecracks shouldn't be taken too seriously. But we must point out there are characteristics most objectionable and reprehensible about Jean-Paul and Simone that cannot be doubted. We know these revelations will be difficult for all true fans to believe, but we must be honest and accept the facts.

They liked Johny Wayne movies.

And so in the end we have to ask what would be Jean-Paul's assessment of his life? Of course, we don't know as he's no longer with us. But as like as not he would have shrugged his shoulders, drawn himself up to his full five feet, popped another amphetamine, downed another whiskey, lit another cigarette, and said:

Although we must realize that since freedom is what you do with what's been done to you, we can be sure that nothingness lies coiled in the heart of being and yet the appearance of the other in the world corresponds to a congealed sliding of the whole universe.

And with Sidney Brand, we can say:

"I understand."

References

Jean-Paul Sartre: A Life, Annie Cohen-Solal,The New Press, 2005.

Sartre for Beginners, Donald Palmer, Writers and Readers, 1995

The A to Z of Existentialism, Stephen Michelman, Scarecrow Press, 2010.

"Jean-Paul Sartre", Wilfrid Dean, Encyclopedia Britannica. No longer available in hardcopies, the Britannica is still not a bad place to find stuff, http://www.britannica.com/biography/Jean-Paul-Sartre

Papa Hemingway, A.E. Hotchner, Random House, 1966.

"Functional Psychology and the Psychology of Act: II", Edward Bradford Titchener, The American Journal of Psychology, Vol. 33, No. 1, pp. 43-83, 1922,

"The Philosophy of Existence: Its Structure and Significance", Julius Kraft Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, pp. 339-358, 1941.

"Concerning Kraft's "Philosophy of Existence" Fritz Kaufman, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, pp. 359-364, 1941.

"Kaufmann's Critical Remarks About My 'Philosophy of Existence', Julius Kraft, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, pp. 364-365, 1941.

Jean-Paul Sartre: Hated Conscience of His Century, Volume 1: Protestant or Protester?, John Gerassi, University Of Chicago Press, 1989.

"Contemporary German Philosophy", Arthur Liebert, The Philosophical Review, Vol. 42, No. 1, pp. 31-48, 1933.

L'imaginaire, Jean-Paul Sartre, Librairie Félix Alcan, 1936. The first first edition.

L'imaginaire, Jean-Paul Sartre, Gallimard, 1940. Also cited as a first edition.

Sartre Explained: From Bad Faith to Authenticity, David Detmer, Open Court.

"Who Did Not Collaborate?", Ian Burum, The New York Review, A review of And the Show Went On: Cultural Life in Nazi-Occupied Paris by Alan Riding, February 24, 2011.

The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell: In Front of Your Nose, 1945-1950, George Orwell, Harcourt Brace, 1968.

"Review of Jean-Paul Sartre's 'Portrait of an Antisemite'

"Letter to Frederick Warbrug, October 22, 1948"

Simone de Beauvoir: A Biography, Deirdre Bair, Jonathan Cape, 1990.

Philosophers Behaving Badly, Mel Thompson, Nigel Rodgers, Peter Owen Publishers, 2004.

"Stand By Your Man: The Strange Liaison of Sartre and Beauvoir", Louis Menand, the New Yorker, September 26, 2005.

Sartre: The Road to Freedom, Louise Wardle (Producer Director), 1999.

Letters to Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir Radius, 1991.

A Disgraceful Affair: Simone de Beauvoir, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Bianca Lamblin, Bianca Lamblin, Northeastern, 1996.

"Jean-Paul Sartre, In His Own Words (Brace Yourself)",Michel Onfray, World Crunch, July 10, 2011, http://www.worldcrunch.com/culture-society/jean-paul-sartre-in-his-own-words-brace-yourself-/c3s3262/. Original Title: "The Century of Sartre".

"The Philosopher and the Terrorist", Felix Bohr and Klaus Wiegrefe, Der Spiegel, February 2, 2013

"Turned down the Nobel Prize - wanted the money in secret", Today's News, October 12, 2012. (On-line Story: "Tackade nej till Nobelpriset - ville ha pengarna i smyg", Dagens Nyheter, http://www.dn.se/ekonomi/tackade-nej-till-nobelpriset-ville-ha-pengarna-i-smyg/.

The relevant part of the article is:

The French writer and philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre was awarded but declined the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1964. He claimed this was to safeguard his freedom and made it a rule not to receive official honors. But in his memoirs, Memories, Only Memories, [Minnen, bara minnen] [Nobel Prize] Academy member Lars Gyllensten claims Sartre approached him several years later and asked for the prize money. But by then it was too late.

The memoirs referred to is:

Minnen, bara minnen, Lars Gyllensten, Bonnier 2000.

The relevant excerpt of the book is:

Bland övriga kuriositeler rörande Nobelpris kan vad som inträffade med Jean-Paul Sartre nämnas. Sartre tilldelades Nobelpriset i litteratur är 1964. Ryktet hade dä kommit ut i förvag om detta - och Sartre vägrade att ta emot priset Varför? Kanske därför att han ville speciminera inför den skock av klichéradikala ungdomar som omgav honom? Kanske för att hans antagonist och litteräre rival Albert Camus hade fätt priset före honom, är 1957?

Hur som helst hörde Sartre eller honom närstäende av sig drygt tio är senare, i september 1975, genom ombud - med förfrägan om han kunde lyfta pengarna. Detta var emellertid omöjligt - beloppet hade fonderats inom Nobelstiftelsen och var inte langre tillgängligt.

And as far as a Fumbling CooperToons Translation goes, this says:

Among other oddities regarding the Nobel Prize is what happened with Jean-Paul Sartre. Sartre was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1964. But the word had gotten out beforehand - and Sartre refused to accept the award. Why? Because he wanted to aspire to the gaggle of stereotypical radical kids who surrounded him? Perhaps because his antagonist and literary rival Albert Camus had won it before him, in 1957?

In any case, ten years later, in September 1975, Sartre or his relatives asked via a representative if he could have the money. However, this was impossible - the amount had been returned to the Nobel Foundation and was no longer available.

So it's not really definitive if Jean-Paul was the mover and shaker of trying to get the cash. But probably he was.