Jessie and Auguste and Camille

Jessie Lipscomb

Assisting Auguste

In 1884, Jessie Lipscomb has been a graduate from the National Art Training School in London (now the Royal College of Art) for about three years. Now she wanted to take the next step for a proper art education which was to study in France. But in that day and age, it was quite daring for a young woman to wander unescorted around Europe, no matter how noble her ambitions. But at twenty-three, Jessie was a determined and forthright young lady who knew how to take care of herself. So her mom arranged for her to stay with the Claudels, a Parisian family whose father was a banker and whose son, Paul, was getting ready to begin his long (and successful) climb in the dual careers of poet/playwright and as an officer in the French diplomatic service.

The Claudels' younger daughter, Camille, was also a sculptress and had set up her own sculpture studio which she shared with some other young ladies. Teaming up with Camille was a real boon for Jessie since Camille's teacher had been Alfred Boucher who was a friend Auguste Rodin who was at the time was beginning to emerge as France's most - no pun intended - august sculptor. Soon Camille and Jessie met Rodin, and he invited the two girls to join his studio.

For a long time, women had been considered too dainty for chisel and hammer or for slapping clay about (this was long before mud wrestling). But the times they were a-changin', and an increasing number of women sculptors were appearing in France's offcial Salon. Still, few art schools, particularly in Europe, admitted women. Fortunately, many of the art professors at the all-male schools - some of whom were really great artists - were open to teaching women privately. Even the traditional and conventional (and quite good) Jean Leon Gerome had women students, among them Mary Cassatt who simultaneously painted pictures that had wide appeal and was invited to exhibit her paintings with the Impressionists. As for Auguste, he had a number of women students, and in fact was known to be quite fond of young ladies in general, and of Camille in particular.

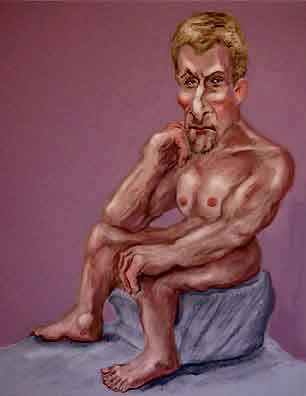

Auguste Rodin

He liked the ladies.

Well, let's put it a bit more forthrightly, folks. Rodin was a randy old cuss who used high-falootin' and high-minded rationalizations to justify banging on his models.

Contrary to what many think, Rodin himself did relatively little of the actual sculpture. As he became more and more successful, he would content himself to crafting small clay "sketches" and turn the idea over to an assistant. Sometimes he would not even bother making the sketch but just give verbal instructions and stood by and watched as the work went along. Auguste, in effect, saw himself as the creative brains of the organization, and he saw no problem with relegating virtually all of the hands-on work to his students, assistants, and the advanced assistants (like Camille and Jessie) who were actually professional artists in their own right and the practiciens.

With their skill and training Jesse and Camille were fully fledged practicienes although when to writing Rodin, Jessie always styled herself as his student. It was Camille, by the way, who did the actual clay modeling of the hands of the famous Burghers of Calais and Jessie helped put clothes on the originally naked burghers. Eventually Camille, like many of Auguste's practiciens, began to wonder why the heck Rodin had his name of the statues and not the people who did the actual work.

Camille also became one of the marble sculptors (Rodin never carved anything in marble himself) while Jesse remained a modeler of clay. In any case, the work was hard, the hours long, and the pay low. Twelve hour days were the norm and one stone sculptor (who had to take legal measures to get paid) once put in a month of 90 hour weeks. Still, it was the norm (and still is) that the assistants were producing their work "for-hire", and that the owner of the studio was the official artist.

As the relationship between Auguste and Camille went from teacher/student to hot and steamy then to a chilly professionalism and finally active suspicion, resentment, and hostility, Jessie found herself playing the part of the go-between friend for both. For his part Auguste appreciated Jessie's overall levelheadedness, and in later years if he was in England he would stop by her home to visit. They remained on good, although formal terms until Auguste died on November 17, 1917.

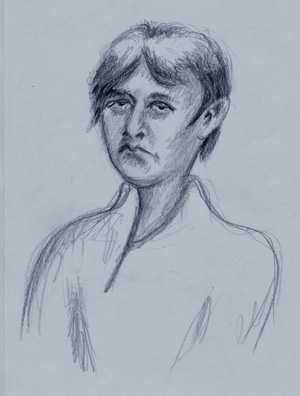

Camille Claudel

La Practiciene

Jessie's life has not been as well documented as Camille's or Auguste's probably because she suffered from a Severe Case of Normalcy. After her return to England, she married William Elborne a chemist (pharmacist) who taught for a while at the medical school at the University London and then pursued further studies at Cambridge where he later became a public analyst in nearby Peterborough. For her part, Jessie was happy to settle down to become a wife and mother and - after making allowances for the inevitable hassles of married life - lived happily ever after. Contrast this with the life of Camille who, although her works are now considered to rival those of Auguste, finally moved into her own studio where she created artwork which she then smashed with a sledgehammer, sent an envelope stuffed with cat poop to a minister of the French government, and would greet visitors (including paid models) holding a cudgel studded with nails. She became convinced that Auguste was out to steal her ideas and that the Dreyfusards were out to get her. In 1913 her family had her committed to the mental hospital at Neuilly-sur-Marne.

Camille remained hospitalized until she died 30 years later. Her death was hastened because the institution was in Vichy France which in 1940 was under Nazi control. Needless to say the Nazi's had no interest in maintaining support of people whom they considered "useless eaters", and although they didn't ship the patients off to concentration camps or execute them outright (which happened at some places), the government support was cut back to a minimum. By 1943, patients were literally starving to death and at a rate of four or five a day. Weakened by poor diet, Camille fell ill in October and died on the 19th.

The doctors had been recommending for years that the family take her back home. But Camille's mom had become quite disgusted with her daughter's bohemian lifestyle, her affair with Rodin, and her oft professed lack of religious belief and just didn't want the little truie around. The religious Paul also rationalized that Camille's confinement was God's punishment because of they way she dealt with a problem that arose after her - ah - "contact" with Rodin. Which is a strange thing to say since it was Paul, not God, who committed Camille.

Although she was put in what was then called sequestration, Camille began to show improvement and when she was permitted visitors she seemed lucid enough. In fairness to the family, though, Camille's mental state was variable. She might be lucid enough for a while, but then suffer relapses where her delusions and behavioral problems returned. Only those who have had first hand experience dealing with the mentally disturbed (even if periodic) know it is not something for which the average family is really equipped.

Naturally a miserable and tragic life like Camille's makes more interesting reading than a happy conventional existence like Jessie's of whom no one has written any substantial biography. Most information we have on Jessie is from Camille's biography by Odile Ayral-Clause with bits and pieces from books about Rodin.

Jesse and William continued to live in Peterborough, a small town which was a bit dull for a lady who had lived in Paris in its artistic heyday before the fin de siècle. But she and William liked to travel and despite William's rather modest income, once even took a trip to Egypt - not an easy journey in the early twentieth century. In 1929, Jesse learned that Camille was confined at Neuilly-sur-Marne, and she and William stopped by on their way to Italy. Afterwards she sent a photograph of Camille to Paul (William was a good photographer). Paul had only visited his sister a couple of times over the years. Jesse's letter was polite but somewhat chiding and had no practical effect on the decision of Paul or Camille's older sister, Louise to leave Camille where she was.

Jessie herself never entirely abandoned art, but being a mom of four children in Victorian and Edwardian England occupied much of her time. She set up a garden studio where she would model portraits of her family and continued to work as time permitted and until old age intervened. She died at age 90 on January 12, 1952, a date of some interest in other respects as well.

References

Rodin: The Shape of Genius, Ruth Butler, Yale University Press (1996). About Auguste but of course it also has quite a bit about Camille and some information on Jessie. Auguste Rodin and Camille Claudel, J. A. Eisenwerth Schmoll, Prestel (1994). This book has a lot of Camille's work and allows you to compare her stye and work with that of Auguste. Overall, a CooperToons Art Opinion is that there are many similarities between the works of the two artists, but quite a few differences as well.