The Kingston Trio

(With a discussion of a song that transformed national and world culture and lifestyles with supplementary information about ante- and post-bellum rural America, 19th century health and medicine, gender inequality before modernization of society, proper attribution of traditional legacies, and local politics in New England)

(Click on the image to zoom in and out.)

Whether the week of September 28, 1958 was a week where absolutely diddly happened or whether it was a week that truly changed the world remains a matter for study, discussion, and debate. Certainly some scholars will argue for the latter case.

So what happened that week? Well, the Carolinas were cleaning up after Hurricane Helene brushed by the coast. Then in a broadcast of a professional sport that had so far garnered little attention, the not-yet Washington Commanders defeated the team that 25 years earlier had borne the proud name of the Steagles. Instead a more widely viewed program was aired the same day where Ed Sullivan hosted a "World Series Preview" featuring Mickey Mantle, Yogi Berra, and Whitey Ford. And across the ocean, Charles De Gaulle was celebrating a personal victory after a national referendum approved the Constitution of the Fifth Republic of France. Now Charles would scrap proportional representation which insured that all political parties would have appropriate representation in the French National Assembly. It would be replaced by the system enjoyed in the United States and Britain where a party could win 51% of the popular vote and take up all the seats while the other parties would have no representation at all.

And during that week and stuck away in a magazine that few Americans ever read was a notice that the song "Tom Dooley" had broken into the Top 100 most popular tunes. As to why scholars consider the appearance of a pop song recorded by a group of crop headed recent college grads could alter forever a world where everything - sports, politics, warfare - had become forms of entertainment is worth a moment's pause.

Alan Freed

Invented R&R?

Davey Guard, Nick Reynolds, and Bob Shane had been singing at parties and then at small clubs in the San Francisco area since the mid-1950's. They had been playing a lot of calypso songs inspired by Harry Belafonte and after trying out several names for the group, they decided on the capital of Jamaica.

But as the Kingston Trio, they also sang what are called "Anglo-American" folk songs. Unlike a lot of other fledgling "folkies" most of whom tended to congregate along the urban coasts, Davey, Nick, and Bob sang with professional polish and pleasant harmonies. Their skill eventually found them playing at the Purple Onion night club in San Francisco. The managers of the Onion deliberately sought to pack the house by focusing on new talent, both stand-up comedians and musicians. This kept the entertainment fresh, new, and (we must admit it), cheap.

It didn't take long for the Kingston Trio to pull in the attention of the executives at Capitol Records. Their first album was commonsensibly called The Kingston Trio and they slipped in "Tom Dooley" almost as a filler. The song, though, proved poplar when the radio stations began playing it.

"Tom Dooley" hit the Billboard Charts on September 29 at #83 and began its meteoric rise. By November 12, it had reached #1 and by December 15 there was a full page story about the new hit song in Life Magazine. For those of too young a vintage to remember when magazines were non-electronic devices with white flappy things in the middle, Life was the most popular photo-illustrated periodical in the United States from the mid-1930's until it folded in 1972. Then in May, 1959, "Tom Dooley" landed the Grammy Award for best Country and Western song.

Ha? (To quote Shakespeare.) Did you say the best Country and Western? I thought we were talking about folk music.

Well, yes, we were. But you see 1958 was a strange year. People were looking to the future as a time of high technology. High school yearbooks had space age or atomic motifs, science fiction movies were the rage (despite incredibly cheesy special effects), and the first satellite - the "Sputnik" - was launched and orbited the Earth for a whopping three months.

But people also looked back to - quote - "simpler times" - unquote - as a - quote - "better way of life" - unquote. You could still find cars with running boards, "westerns" were among the most popular shows on television, and personal correspondence was considered horribly gauche unless it was written in longhand (and sent at the now outrageous cost of 4¢ per stamp).

But most of all, good citizens were clamoring for wholesome and moral and

music.

music.

Rock sounded a lot like ...

Glenn ...

... Benny ...

... and Tommy.

The Truck Driver from Memphis

You see, in the early 1950's there had been a new and disturbing trend in the music being favored by young people. It was called (bleah) "rock and roll", a term that Cleveland disc jockey, Alan Freed, claimed to have invented in 1951. But nothing really happened for a couple of years since the music Alan advocated often sounded a lot like the big bands of Glenn Miller, Benny Goodman, and Tommy Dorsey.

But then a swivel-hipped truck driver from Memphis began appearing at VFW halls and high school auditoriums where the kids in the audience went nuts whenever he gyrated across stage. Older Americans were horrified at these displays which could only lead to the destruction of American democracy and its moral fiber. Soon there was an outcry to restore

music to what it was B.E.1 Some towns banned rock and roll concerts altogether.

music to what it was B.E.1 Some towns banned rock and roll concerts altogether.

The problem, though, was not really with the music, but with its presentation. In fact how you classified music was more or less arbitrary. When Chuck Berry sang "Johnny B. Goode" it was raucous and horrid rock and roll. But when Buck Owens and his Buckeroos played it, it was good, wholesome, and cornfed country and western. When Buck sang "Act Naturally" it was honest, moral, and patriotic country music. But once the Beatles added it to their concerts their rendering was the undisciplined noise of rock and roll and leading the world's youth to perdition and ruin. Then when The Saddlemen were playing "Rock The Joint" it was healthy and country. But once they doffed their cowboy hats and boots for prom coats and bow ties2 and became Bill Haley and His Comets, the song was (yet again) rock and roll.

They also wore trousers, of course.

There was also confusion in the nomenclature. On June 18, 1949, "Lovesick Blues" by Hank Williams reached the #2 spot, and it was listed in Billboard as a "folk" song. But a week later - July 26, 1949 - "Love Sick Blues" had climbed to the top. But although it was still part of the "folk" category, it was labeled parenthetically as a new sub-genre, Country and Western. But in keeping with the nostalgia of the time, the name still commonly used - even by Hank himself - was "hillbilly".

Hank Williams

Country, Folk, or Hillbilly

So when the first Grammy Awards were presented in May 1959, folk, country, and yes, "hillbilly" were one and the same, and giving the first - quote - "Country award" - unquote - for "Tom Dooley" was simply keeping with the times. The next year's "Country" award went to Johnny Horton and "The Battle of New Orleans". This was originally written by a high school principal from Arkansas to help his students remember their history. But it wasn't really country. It wasn't until the 3rd Grammy Awards of 1960 with "El Paso" by Marty Robbins that a clear-cut country song was honored with a Country Grammy.

But whatever you wanted to call it "Tom Dooley" was a hit, and by most (unreferenced) sources, it sold 6,000,000 copies. Even at 2¢ per record that would make a nice bit of change for the singers.

Yes, yes. But having a best selling record scarcely makes a cultural paradigm shift. What made "Tom Dooley" different than "Swanee", "Chatanooga Choo Choo", or "In The Mood"?

Well, the consensus is virtually unanimous that it was the Kingston Trio and "Tom Dooley" that kicked off what has become known as the Folk Revival - or as some call it the "Folk Craze" - of the 1960's.

After "Tom Dooley" folk music was everywhere. Folk festivals found new popularity, and new groups sprang-up that were clean, wholesome, and could sing in-tune: The New Christy Minstrels, (with a pre-First Edition Kenny Rogers), the Greenbriar Boys (with future Smithsonian executive Ralph Rinzler), and the Limelighters (with sailing enthusiast and humanitarian Glenn Yarbrough). Moe Asch's Folkways label got a major shot in the arm, and folk "collectors" began fanning out to the hills and valleys and began discovering folk singers some of whom, like Mississippi John Hurt and Dock Boggs, had recorded for major labels in the 1920's and 30's. Some of the newer "discoveries" like Doc Watson later went on to mainstream iconicity.

Moe Asch and Folkways

A Shot in the Arm

Doc Watson

Mainstream Iconicity

Folk music even went on television. Not only was there a plethora of TV specials but folk music even had it's own weekly series, for Pete's sake! That was Hootenanny which ran on ABC for two seasons, 1962 and 1963, and was hosted by Jack Linkletter who was, yes, Art's son.

Of course, the Kingston Trio hit the big time television shows - Milton Berle, Garry Moore, Patti Page, Dinah Shore, Perry Como, Steve Allen and Jack Benny. Naturally the Trio performed in night clubs, some of which were dedicated solely to folk music.

But where they really found a lucrative venue was on college campuses. Forget the "lectures" where you'd have 30 people show up in an auditorium. Instead the Kingston Trio played to packed field houses. So whenever you see a popular group performing to capacity crowds at your local college, remember this began with the Kingston Trio. And everywhere they sang "Tom Dooley".

"Tom Dooley" even inspired a movie, for crying out loud! In 1959, Michael Landon - then an up and coming actor, who had put in a surprisingly well-received performance in I Was a Teenage Werewolf - starred in The Legend of Tom Dooley. Although departing from the song's story considerably, the film received decent reviews. The next year Michael went on to stardom as Little Joe, Ben Cartwright's youngest son, on the TV show Bonanza and later he assumed the role of the father, Charles Ingalls, in Little House on the Prairie.

At this point, though, other scholars will step in and say, hold on there, pilgrims. Yes, the Kingston Trio was popular. But the Folk Song Revival had been launched nigh on twenty-years before, in 1940. That's when there was a "Grapes of Wrath" concert in New York City. Organized for the benefit of migrant workers, it featured some of the true Titans of Folk: Pete Seeger, Burl Ives, and even Woody Guthrie.

After the concert, for the next decade folk music could be found on the radio, both on nationally broadcast specials - like Back Where I Come From - and regularly scheduled programs like Pipe Smoking Time which (briefly) starred Woody Guthrie. Then Pete Seeger with Ronnie Gilbert, Fred Hellerman, and Lee Hayes formed the Weavers. This was the first really commercially popular folk music group and they even made what are arguably the first music videos. Of course these necessarily had to be shown in movie theaters since at the time most people didn't have television sets. Then the Weavers had a hit with the Leadbelly composition, "Irene Goodnight" which became the #1 most popular tune of 1950. That was eight years before "Tom Dooley" hit the airwaves!

The Weavers

Pete, Ronnie, Lee, and Fred

Yes, this is all true enough. But that first Folk Music Revival had nowhere near the impact of its incarnation of the 1960's. The early audience was fairly limited (big band music was still popular) and in any case the leftist politics of the musicians soon forced the early folk groups off the scene.

The Kingston Trio, though, and their songs were decidedly non-political. So everyone could enjoy them. Certainly neither Nick, Dave, nor Bob had backgrounds that would cause mainstream networks or their commercial sponsors embarrassment (in his youth Pete Seeger had been a card-carrying member of the Communist Party).

But most of all, three young men with button-down shirts and short hair who crooned "Michael Row the Boat Ashore" were deemed more suitable for American youth than Chuck Berry belting out "My Ding-a-Ling". And despite parental approval, a lot of the kids liked the Kingston Trio, too. So Nick, Davey, and Bob formed a bridge between the counterculture - still being called "beatniks" well into the mid-1960's - and mainstream America.

The Fab Four

Soon to appear ...

... on a really big shew.

Elvis

He faded from sight.

Sadly, despite their popularity, the Kingston Trio - and the Folk Craze - soon faded. Much of the decline had to do with what historians now call the English Invasion of 1964. With the Fab Four soon arriving to appear on Ed Sullivan's really big shew, rock came back and with a vengeance. And to the surprise of many it returned without Elvis who now appealed to the adults and who was performing in grown-up venues like Las Vegas.

All right, already! But what about the Kingston Trio. What happened to them?

Like many music groups that dropped from sight, the Kingston Trio continued to perform to the point that people were surprised to find they were still around. And even though Nick, Davey, or Bob are no longer with us, the group still is and so provides us with the modern alternative to Plutarch's Paradox of the Ship.

Less Celebrity?

Paul and Art?

Joan?

Arlo?

Joni?

... or even Bob?

But what didn't fade is the influence of the Kingston Trio. Without the Trio and "Tom Dooley", there would have been far less celebrity for the "folk rock" stars like Peter and Gordon, Chad and Jeremy, Buffalo Springfield (with Stephen Stills), Cat Stevens, Judy Collins, James Taylor, Simon and Garfunkel, Crosby Stills Nash and Young, Gordon Lightfoot, The Lovin' Spoonful (with John Sebastian), Carly Simon, The Mamas and the Papas, Joan Baez, Arlo Guthrie, Don McLean, Peter Paul and Mary, John Denver, Joni Mitchell, and Richie Havens. Even the Smothers Brothers, the popular (and at times controversial) comedy folk duo, explicitly stated that they would never have had their success if there hadn't have been a Kingston Trio leading the way.

And - dare we say it? - we might never have heard of the 2016 Nobel Laureate for Literature, Robert Allen Zimmerman.

Their influence didn't stop with rock and rollers playing acoustic guitars. The Folk Revival also led to acceptance of the broader definition of "folk music". Bluegrass became acceptable for young urban fans to listen to, and full fledged country singers - Johnny Cash, Glenn Campbell, and even Jimmy Dean - entered prime time entertainment. Then rock and roll stars - Conway Twitty, Leon Russell, John Fogarty (of Creedence Clearwater Revival), and Kenny Rogers - moved into country music and became superstars.

Well, all this is fine and dandy, but dang it, what's this about Tom Dooley? Just what distinguishes this "story song" from others like "Me and Bobby McGee", "Big Bad John", or even "A Boy Named Sue"? We'd really like to know this.

I thought you would as Captain Mephisto said to Sidney Brand. It's really very simple.

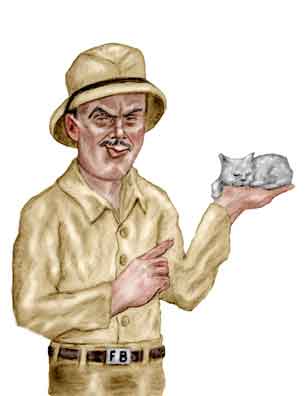

Real People

Wyatt ...

... Casey ...

... and Frank.

Today there are people who don't realize that the likes of Wyatt Earp, Casey Jones, and Frank Buck were in fact real people. Yes, Wyatt Earp really did have a gunfight near the O. K. Corral in Tombstone, Arizona. Casey Jones really did die in a train crash and was a brave engineer. And Frank Buck really did write a book of his real life adventures titled Bring 'Em Back Alive although his critics maintain a better name would have been Kill Half of 'Em Along the Way.

And there are even fewer people who know that there really was a Tom Dooley. And virtually no one knows that the facts, as is often the case, are far more interesting than any legend.

First of all, Tom's name was spelled Dula. But from the vagaries in the spelling of the old time census takers who obtained their information from people who could neither read nor write, it's clear that the pronunciation was in fact Dooley. For some reason certain regional dialects switch the -a sound (pronounced -uh) and the long -i or -y (pronounced -ee). So we have Missoura for Missouri and Opry for Op(e)ra. And as we said Dooley is what the Blue Ridge residents of North Carolina said for Dula.

And there really was a Laura Foster. She was seen riding east near Ferguson, North Carolina, on May 25, 1866. Where she was going was anyone's guess and she was never seen alive again.

Most suspiciously Tom had been acting strange once Laura went missing and he, too, soon vanished from the area. Two deputy sheriffs were dispatched to Tennessee where they found him and took him into custody. The story attracted widespread national interest and accounts appeared in New York newspapers.

In his voice-over introduction to the song, Nick said that throughout history there has been the story of "the eternal triangle". The story involved Tom, a sheriff named Grayson, and a beautiful woman named Laura Foster. Yes, that's the song's story. But the real story was more about a "temporary pentagon" involving Tom, Laura Foster, Laura's cousin Pauline, another cousin named Ann Melton, and Ann's husband, James.

James Melton and Ann Foster were probably married around 1858. James was considerably older than Ann, probably in his thirties, and Ann was still in her teens. James seems to have been a rather placid gentleman while Ann was quite the gadabout.

Ann's mother was Carlotta Foster - called "Lotty" by her friends - and despite bearing five children, she evidently considered getting married an unnecessary inconvenience. Not that she didn't want her children to grow up "right", mind you. In 1859 and after Ann was already married, Lotty went into the Melton's cabin and found Tom and Ann snug beneath the covers. Tom immediately dived under the bed and Lotty upbraided him for his irresponsibility.

But soon there was a war on - The Civil War, that is - and in 1862 Tom signed up. He was about 17 at the time and had been born in Happy Valley, North Carolina, on a farm south of the Stony Fork Road (now the modern Gladys Fork Road). The Dula farm was run by Tom's widowed mother and was situated on Reedy Branch Creek which is an often undesignated tributary of the Yadkin River. For those with access to historical land deeds and titles the location can be pinpointed without much trouble.

However, for those with less of a documentary arsenal, there is a published map of the area drawn right after the Civil War. From this map - termed "crude" by one historian - plus additional information in Tom's biographies allows pinpointing the Dula family farm pretty nearly (to quote Sir Isaac Newton). The farm is now on private land and the closest approach is on an unpaved road and those familiar with the terrain advise caution when using it.

Map of "Dooley Land"

(Click on the Image to Open in a New Expandable Window)

When Tom signed up with the Rebs he was designated as a "musician". Military musicians in the Civil War were mostly drummers or brass players but there's no indication of Tom's speciality. However, there is reliable documentation that Tom was a capable fiddle player and so we can expect him to have been in demand for the square dances that were common in the Appalachians. During the war Tom spent some time in the hospital although whether he was wounded or just ill isn't clear. He was later captured by the Yanks, spent some time as a prisoner, and was released after signing an oath of loyalty to the United States.

Tom, now twenty, returned to his home and immediately took up residence with - you guessed it - James and Ann Melton. There were three beds in the one-room cabin, but it seems that all three couchés were not used equally. James preferred to sleep alone and Ann and Tom often decided to reduce the amount of bed linen that needed mending by leaving one bed unoccupied. Again James seems to have either looked the other way or was an incredibly sound sleeper.

About that time one of Ann's cousins, Pauline Foster, took up residence with the Meltons as a paid housekeeper. Pauline was a pretty girl who liked to tell jokes. Or at least she said she was joking whenever she said had killed someone.

Pauline's visit wasn't just a friendly social call. One of the larger land owners was George Carter who just happened to be the only bonafide medical doctor in the area.

Pauline, it seems, was seeking treatment from Dr. Carter for what the English call the French Disease, the French called the Neapolitan Disease, the Turks call the Christian Disease, and their parishioners call the Vicar's Disease3. But in Reconstruction Era North Carolina, it was just called "the pock".

That's a joke, by the way.

If James, Ann, Tom, and Pauline weren't enough to crowd a one room cabin then another cousin of Ann's would often drop by. That was Laura Foster (pronounced regionally as LAHR-ree), a local girl who lived with her dad, Wilson, about five miles from the Meltons. Like Ann and Pauline, Laura was a pretty girl although her sunny smile displayed horse-sized incisors separated by a noticeable gap (diastema). Wilson, by the way, had once found his daughter showing her affection for Tom. And when we mean she was showing her affection, we mean she was showing her affection.

We see then that after the Civil War, Tom was an energetic young man and he kept himself busy but not with work. In fact, the farming of the region seems to have been conducted largely by the women, whether it was checking on the cows (who were allowed to roam free), milking the cows (they usually wandered home by themselves in the afternoons), or "dropping corn". That is, they'd drop corn seeds in the furrows and later the dirt would be piled loosely on top.

Presumably the menfolk did some work like providing meat for the tables by hunting. But it's also clear that they had a lot of free time on their hands. This they put to use, if not good use.

A word or two more about this wholesome rural life in Good Christian Rural Victorian America. Despite the best efforts of the members of the cloth, the parishioners often strayed from the righteous path. In fact, it seems like they didn't even give a rip. A news reporter came down to North Carolina to provide copy about Tom and his neighbors for the New York Herald. The tone of the article is decidedly negative, saying that a "state of immorality unexampled in the history of any country exists among these people and such a general system of freelovism prevails that it is 'a wise child that knows its father'."

With this set-up - an older and rather indifferent husband married to a 23 year old whoop-it-up party girl, a 21-year old and rather vigorous young man living with them in a one-room cabin, and two comely and attractive cousins either living in or frequenting the cabin - we can expect a right lively time even with the most normal of circumstances.

Of course, with one of the young ladies seeking - ah - "treatment", these were not normal circumstances.

It wasn't long before Tom noticed there was a, well, we'll call it a "blemish" on what the Roman writer Pliny the Younger called "the parts that are held in reverence". He deduced that he, too, was a candidate for Dr. Carter's treatment. Of course, soon the whole bunch - Laurie, Ann, Pauline, and Tom - were "pock-marked" so to speak. The possible exception seems to have been Ann's husband, James, who apparently remained in the bloom of health.

In the 19th Century, treatment for the malady was unpleasant, toxic, dangerous, and completely ineffective. The - quote - "medicine" - unquote - was a combination of "bluestone" (ergo, copper sulfate) and "blue mass" (a mixture of mercuric chloride with other useless ingredients). Now at that time if a young man found that after a night with Venus he was looking forward to a lifetime with Mercury, he put all the blame on the lady. Such a double standard between the genders existed at least up to the mid-20th century, and Tom was no different than other young men of the era.

But here's the kicker. Tom had decided it was Laura who was the transmitter of le grande verole, not Pauline. Then once Ann began experiencing symptoms herself, she believed (correctly) that she had become infected from Tom. So following Tom's lead, she figured (incorrectly) that Laura was to blame.

We have to admit it. In all the accounts and documentation about Tom Dula, he doesn't come off that quick in uptake. Instead he strikes us more as a hot-to-trot Jethro Bodine. Certainly given that the deed was done and could not be undone, Tom did not act in a particularly rational manner. For one thing, he couldn't keep his mouth shut. He even griped to a friend about his condition and that he was "going to put through the one that gave it to me." Tom's friend advised him not to do it.

On Thursday, May 24, 1866, Tom was seen holding a "whispered" conversation with Ann and he then borrowed a mattock - a pick-like digging tool - from Ann's mom, Lotty Foster. He wasn't seen for the rest of the day. Then sometime after her conversation with Tom, Ann left her house and was gone all night. She returned the next morning and slept most of the day.

On Friday, May 25, Laura was seen riding east on her father's mare. She was carrying a bundle of clothes and told a friend she was leaving to get married. The next day the mare returned but with the saddle empty. It also appeared the bridle had been gnawed through - as if the horse had been tied up and left by herself only to break free.

Despite the strange episode of the horse, people weren't really worried. No one had 9 to 5 jobs and so there was flexibility in their schedules. Travel was also slow and often difficult and simply visiting relatives often meant you'd be away for weeks. So when Laura rode off and was gone for several days, no one thought anything about it.

At least not for a while. But as the days passed and no one heard any more of Laura, people began to think that the taciturn Tom wasn't telling all. Most suspiciously when searches were organized, he refused to help.

For his part Tom played the aggrieved victim. Why, with all the slanderous murmurings now being leveled at him, he was going to have to pull up stakes and go off elsewhere. He'd find a new home and then have Ann and her mother come live with him (Tom said nothing about accommodations for James). He then headed off for Tennessee.

Pauline certainly wasn't helping matters. Someone asked if she knew anything of what happened to Laura. She just snorted, "Me and Tom Dula killed Laura Foster." Her odd response has led some to believe Laura had a tendency to take more corn-squeezin's as was good for her. Later Laura said he had just been joking.

But after Ann heard that Pauline had shot off her mouth, she picked up a club and headed out of the house. When the two women encountered each other, Ann yelled at Pauline. "You have said enough to hang you and Tom Dula if it was ever looked into." Pauline returned the vituperation. "You are," she shot back, "as deep in the mud as I am in the mire." The altercation got a bit physical but seems to have been stopped before it went too far.

By now everyone was convinced Tom had killed Laura, and that Pauline was involved as well. Pauline was arrested and two deputy sheriffs from Wilkes County headed to Tennessee. They learned Tom was working on the farm of James Grayson near the small community of Trade which was only about a mile west of the state line. So to escape from a murder rap, Tom had only gone about 25 miles from his home (we said Tom wasn't too quick in uptake).

Despite the assurance of the song, James was not a sheriff. But he was a well-to-do farmer and member of the state legislature. Colonel Grayson told the deputies that Tom had been working as a hired hand but had left shortly before. The group, with Grayson now part of the posse, overtook Tom on the road leading to Johnson City. Seeing that resistance was futile, Tom gave himself up.

Tom was put on a horse and his legs tied together with the rope passing beneath the horse's stomach. Tom tried to escape a couple of times but never made it. Back home he was put in a cell in Wilksboro where Pauline was being held.

By now Pauline realized she was in a tight place and the best thing to do was to spill her guts. She swore she had nothing to do with Laura's disappearance but admitted that Ann had told her that Laura had been killed and buried. Pauline insisted that she had not seen the grave itself but she knew the general area where it was. Now as a cooperating witness, Laura directed a search party to about 500 yards north of Tom Dula's house.

The men formed a line and began moving through the woods. It was slow going as they scanned back and forth along the line of the search. Then at one point a horse reared and shied away. Nervously, the men began probing the ground with sticks, and what they found was grisly indeed.

They immediately summoned Dr. Carter who confirmed they had discovered the body of a young female. Decomposition was so advanced that there was no flesh on the face, but there was a cut though the dress between the third and fourth ribs. At that point a knife blade could easily have penetrated the heart.

The group removed what were literally the remains for a formal inquest at Elkville, a small community where Elk Creek joined the Yadkin. Pauline said she recognized Laura's prominent and distinctive incisors as well as the dress. Laura's dad confirmed the body was his daughter as he also recognized the clothes and her possessions. Pauline was released and Ann was arrested.

The legal proceedings followed a surprisingly modern course. Both Ann and Tom were held without bail in Statesville and there were motions filed for severances, continuances, and change of venues, some granted, some denied, and followed by appeals. The onerous and dilatory path of the proceedings may in part be due to the skills of one of Tom's attorneys, Zebulon Vance, who was one of the best lawyers in the state as well as a former governor. Tom and Ann were tried separately and in alphabetical order.

Tom's trial took two days and on October 16, 1866 he was convicted of first degree murder. An appeal was granted and the case retried. But the second trial in January 1868 also ended up with a guilty verdict. After yet another appeal, the Supreme Court finally affirmed the decision. While all this was going on and taking nearly two years, Ann sat on ice.

Tom went to the gallows on May 1, 1868. During the trial he never mentioned Ann, either accusatory or exculpatory. But the previous night he asked for one of his lawyers and handed him a note with instructions that it was to be kept secret as long as he, Tom, was alive:

Statement of Thomas C. Dula - I declare that I am the only person that had any hand in the murder of Laura Foster

April 30, 1868

Tom remained mostly calm but in the early morning he was heard speaking to himself "incoherently" and pacing back and forth with the leg shackles rattling. Then around twenty minutes before one o'clock he was placed in a cart and his sister was allowed to accompany him. The wheels rumbled toward an open field where two rough hewn pine poles about ten feet apart were joined by a crossbeam. The sheriff told Tom he could make a statement.

Tom stood up in the cart and addressed the crowd in what can be described as a rambling tirade. He spoke about his childhood, his parents, his army years, and the Civil War. He also "made blasphemous allusions to the Deity" mostly about the witnesses (who he said lied), and he trashed US politics in general and the Governor of North Carolina in particular whom Tom branded a "secessionist" and was "not to be trusted". During the near-hour long speech, Tom hardly mentioned the crime itself and only then in his gripe that some witnesses lied. And that was pretty much that.

Tom was buried back in Happy Valley a little more than a mile south of the Dula farm on land owned by a cousin. In 1958 a photographer found the marker was simply a white stone hardly noticeable among the weeds. Later a larger monument was installed and is now only about a quarter chipped away. There has been some question whether this is the correct gravesite. After all, you can get residents pointing out a nearby "white oak tree" where they claim Tom "Dooley" was hung. But a researcher who studied the events has concluded the gravesite is probably correctly marked.

Ann went to trial, not for murder, but for aiding and abetting and encouraging Tom to commit murder. But Tom's exculpatory note was introduced into evidence and the proceedings were brief and ended in an acquittal.

Ann only lived another six years and died at age 31 in 1874. The usual account is that she had been in a carriage accident and never recovered from her injuries. However, some have pointed out that the final stages of "the pock" may have hastened her demise. Certainly some people with the malady suffer from "psychiatric manifestations" and people who attended Ann said that at the end she was screaming that there were black cats crawling over the walls and she could hear the sound of frying meat.

Given that today Tom's guilt is taken as a given, it's worth pointing out that a modern and qualified legal opinion is that he was not guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. Nor was he granted due process.

Due process was lacking, we read, since Tom was arrested in Tennessee and not given an extradition hearing. He was simply captured and returned to North Carolina. As far as his guilt, his conviction was based on circumstantial evidence.

Although often pooh-poohed as vague and contradictory (particularly by counsels defending guilty clients) circumstantial evidence is not only admissible in court but can be even more objective than eyewitness testimony. On the other hand, if it is to lead to a conviction, circumstantial evidence is supposed exclude other reasonable alternative explanations. In this case, the evidence cannot exclude the possibility that Ann was the actual murderer and not Tom

It's worth a moment's pause to consider other trials and tribulations - that is, those that the Kingston Trio encountered with the success of "Tom Dooley". Yes, the trials and tribulations of the Kingston Trio's success.

On their label, "Tom Dooley" is listed as "Traditional - Arr. Dave Guard". What this means is the song is a folk song - that is, it's in what's called "oral circulation" - but the composer is unknown. And Davey was the one who made the specific musical arrangement that you heard in the song.

Alan Lomax

However, a folk scholar could - and as a matter of fact, did - point out that the lyrics and the tune the Kingston Trio plays is almost identical to those published in 1947 in the book Folk Song USA. The book was authored by the father-son duo John and Alan Lomax. As to where they got the song, once we turn the pages to the tune itself, we read "Words and music adapted and arranged by Frank Warner".

But...but...but... We thought Tom Dooley was a folksong and "traditional". So why is Frank getting the credit? More to the point, is the song that the Kingston Trio recorded really the same as John and Alan's and hence the same as Frank's and which had been previously printed in a book which claims copyright?

As you may guess, there is disagreement. Certainly there was considerable brouaha when it became clear the Kingston Trio had a hit on their hands. Frank, John, and Alan expressed choler that "their" song had been appropriated without proper credit given and (we must admit it) without royalties being paid. The sheer effrontery of these three young whippersnappers!

But Nick, Dave, and Bob responded indignantly. For one thing they said they had indeed learned the song from "oral circulation". That is they heard it from another folk singer. They then asked him for the lyrics and began to sing the song.

Besides "Tom Dooley" was a folk song, for crying out loud! And it had been sung for nigh on a hundred years. (Well, ninety, but who's counting?) What they sang was their own arrangement - smooth and serious with an original spoken introduction and a modified melody. Why, Nick even throws in a completely new melody toward the end as a counterpoint to the chorus. Their "Tom Dooley" was a new work of art of which John and Alan and Frank had no claim.

Pshaw, replied Frank, John, and Alan. The - quote - "modified melody" - unquote - was simply to stick a quarter note rest after the word "Tom" ("Hang down your head, Tom [pause] Doo-ley"). And their words, except that Nick, Dave, and Bob didn't speak in dialect as in the printed version ("stobbed" for "stabbed"; "tomorrer" for "tomorrow"), were virtually identical to those in the book. The lyrics of a truly distinct arrangement has to be more than just a vowel or two in a folklorist's transcription. And slipping in a rest doesn't alter the fact the basic melody had been previously published. The Kingston Trio, as far as Frank, John, and Alan were concerned, were playing our song!

Now here there are options. Either side can decide to let the everyone sing what they want and let matters be. Or each side can contend with the other, probably dragging everything out for years.

Or you can work out a deal.

Which is what happened. In essence all agreed that any royalties from the recording that accrued past 1962 would be shared. Of course, by that time "Tom Dooley" was no longer on the charts and was no longer the mega-money maker it first was.

But once you think everything is settled, there's one more string that you can twist around the tuning peg. Where, you ask, did Frank learn the song?

Frank Warner had been working for a branch of the Young Men's Christian Association, or the YMCA, in North Carolina. In his spare time he and his wife Ann would go into the hills and find people who would sing folks songs. Frank and Ann would write down the words and music and sometimes managed to record the singers directly on disk.

Among the folk musicians they met was a farmer and carpenter who made Appalachian dulcimers and fretless banjos as a sideline. That gentlemen was Frank Proffitt and one of the songs that Frank sang was, yes, "Tom Dooley".

We have to be honest and point out if the Kingston Trio didn't acknowledge Frank Warner's contribution, neither did Frank Warner acknowledge Frank Proffitt. On the other hand, John and Alan Lomax did mention Frank Proffitt when they published Folksong USA, citing the Folkways album Frank Proffitt Sings Folk Songs in the bibliography. But that album did not include "Tom Dooley".

John Lomax died in 1948, the year after Folksong USA was published. Alan continued the family scholarship, and in 1960 he published Folk Songs of North America which remains one of the definitive folk song anthologies of English language folk songs. He included the song, spelled as "Tom Dula", and stated it was "From Folk Song: USA, copyright, 1947, by Frank Warner and J. and A. Lomax, copyright 1958, by Ludlow Music, with additional verses from Henry, Folk Songs from the Southern Highlands, p. 325."

Nary a word about Frank Proffitt.

In the Folk Songs of North America, Alan made some significant differences in the song as printed in Folksong USA. This just wasn't adding verses from another book, but he created an alternative melody line, although it was not the same counterpoint that Nick sang on the record. And in Folk Songs of North America, Alan did warn the reader that most of the songs as printed were protected by copyright.

Huddie Ledbetter

Leadbelly

Both Alan and his dad were known claiming copyright of many of the songs they printed in their collections. Of course, this practice was just keeping with the standard of the day and the rules were clearly slanted toward the publishers and managers with seemingly little thought for payment to original performers or sources.

One of the more controversial episodes regarding copyrighting folk songs was when John wrote the book, Negro Folk Songs As Sung by Lead Belly. The title page states that the songs were "Transcribed, Selected and Edited by John A. Lomax and Alan Lomax". That seems fine as they weren't claiming the songs were anyone except Leadbelly's, that is, singer and twelve-string guitarist Huddie Ledbetter.

However, the original contract for the book assigned the rights of the songs to the publisher, the MacMillan Company. Huddie certainly had no input in drafting the contract or even saw it.

So whose songs were they? Well, following the title page was the copyright notice. It stated unambiguously:

Copyright 1936

by The MacMillan Company.

All rights reserved - no part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in magazine or newspaper.

So the songs, we read, belonged to the MacMillan Company. And legally Huddie couldn't perform his own songs much less record them without permission. And this even meant Leadbelly's live performances would be hampered since radio stations and theater owners would be understandably reluctant to get embroiled in performances where the ownership of the material wasn't clear.

Eventually MacMillan gave in a little but not much. They insisted on keeping to the original contract but would separately grant Huddie permission to sing the songs royalty-free. It's also worth noting that after his tours with John and Alan were over, one of Huddie's first jobs was cleaning cars for 10¢ a day.

Long after Huddie was dead, the copyright claims were still an issue. In the 1990's Alan, now in his mid-70's, was interviewed on a popular radio program and the topic of the copyright of folk songs was broached. Alan actually became flustered - something that rarely happened - and he had trouble articulating an answer.

To Frank Warner's credit, when the agreement was reached with the Kingston Trio, he stated that part of his share should go to Frank Proffitt. However, it seems little direct payment was made although Frank Proffitt did write a nice letter saying that the song did open doors for him. As the Folk Boom, well, boomed, he was invited to appear at the various festivals. These included the University of Chicago Folk Festival, the 1963 National Folk Festival, the 1964 World’s Fair, and the 1964 Newport Folk Festival. Frank died the next year, age 52.

"Tom Dooley" was and remains the Kingston Trio's best known song. But the #2 tune in their repertoire has to be "M. T. A." or more commonly and loquaciously known as "Charlie On The MTA". The MTA refers to Boston's Metropolitan Transit Authority and the song is one of the Trio's few "political" songs.

In the 1940's the MTA had a complicated fare system. You would board the train at one station, ride to your destination, and if the trip went beyond a certain distance you had to pay an extra exit charge. By the late 40's the MTA was planning to raise the fares, a move that was opposed by mayoral candidate Walter O'Brien. Among Walter's campaign promises was not just to fight the fare increase, but also to simplify the payment system.

Two young ladies, Jacqueline Steiner and Bess Lomax - yes, the sister of Alan - wrote a song against the rate hike. The song was one of several played from O'Brien's campaign trucks and ended up getting the campaign fined $10 for disturbing the peace. We should point out that sound trucks were common for campaigns of the time but Walter was considered a "radical" and a "Communist" which at the time meant anyone who was in favor of equitable pay and civil voting rights for all people regardless of race or ethnicity. So we may be seeing a bit of selective enforcement.

The song was released commercially by folk singer Will Holt - today best known for writing the English lyrics of "Lemon Tree" ("Lemon tree very pretty ..."). But the backlash against "M. T. A." was strong because the song was "celebrating a radical" and soon the record was pulled from circulation. But when the Kingston Trio got the song, the events were ten years in the past, and just for good measure they changed the name of the candidate from Walter to George.

"M. T. A", tells the story about a man named Charlie who on a cold and fateful day put ten cents in his pocket, kissed his wife and family, and went to ride on the MTA.

Well, when Charlie got to the Jamaica Plain station the conductor told him he needed to pay an extra nickel. But Charlie had already handed in his dime at the Kendall Square Station and now Charlie couldn't get off of the train!

The famous chorus tells of Charlie's predicament.

Well, did he ever return?

No, he never returned and his fate is still unlearned. (What a pity!)

He may ride forever 'neath the streets of Boston.

He's the man who never returned.

The song ends up telling the listeners in Boston to fight the fare increase, vote for "George" O'Brien, and so get Charlie off the MTA.

Students of American politics will be interested to learn that Walter lost the election. He moved from Boston and lived his last years working as a school librarian and running a book store in Harpswell, Maine on the north end of Orr's Island.

But fans of "M. T. A." have always noted the conundrum posed by the fourth verse:

Charlie's wife goes down to the Scollay Square station

Every day at a quarter past two,

And through the open window she hands Charlie a sandwich

As the train comes rumbling through!

Hm. If Charlie's wife can hand him a sandwich, why can't she give him a nickel so he can get off the train?

Is it possible that Mrs. Charlie had her own agenda? Well, if so her modus operandi was far superior to that of Tom Dula and Ann Melton.

References and Further Reading

"Hot 100 Gets 13 New Ones", Billboard Magazine, September 29, 1958, p. 3.

"The Billboard Hot 100: September 29, 1958", Billboard.

"The Billboard Hot 100: November 12, 1958", Billboard.

The Kingston Trio - Tom Dooley", Capitol Records, Vinyl 7", 1958.

"Tom Dooley - The Kingston Trio (1958)", William J. Bush, National Recording Board Preservation, Library of Congress.

Folksong USA, John and Allan Lomax, Grosset and Dunlap, 1947.

The Folk Songs of North America in the English language, Alan Lomax, Doubleday, 1960.

Lift Up Your Head, Tom Dooley: The True Story of the Appalachian Murder That Inspired One of America's Most Popular Ballads, John Foster West, Down Home Press, 1993

Ballad of Tom Dula: The Documented Story Behind the Murder of Laura Foster and the Trials and Execution of Tom Dula, John Foster West, Moore Publishing Company, 1970.

"Hanged Man in Hit Tune", Life Magazine, December 15, 1958, p. 81.

"The Death Penalty: Shocking Revelations of Crime and Depravity in North Carolina - Thomas Dula Hanged for the Murder of Laura Foster", The New York Herald, May 2, 1868, Page 7, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"Tom Dooley: The Ballad That Started The Folk Boom", Peter Curry, 1998", The Kingston Trio Place.

"Historic Artist", Frank Proffitt, Musician and Craftsman, Watauga County, NC", Blue Ridge National Heritage Area.

Negro Folk Songs as Sung by Lead Belly, John A. Lomax and Alan Lomax, MacMillan, 1936.

The Life And Legend Of Leadbelly, Charles Wolfe and Kip Lornell, HarperCollins, 1992, Da Capo Press, 1999,

"Charlie on the MTA", Jonathan Reed, Massachussetts Institute of Technology.

"Jacqueline Steiner, cowriter of 'Charlie on the MTA,'", Bryan Marquard, Boston Globe, January 29, 2019.

The Legend of Tom Dula, Michael Landon, (Actor), Jo Morrow (Actor), Jack Hogan (Actor), Stanley Shpetner (Writer and Producer), Ted Post (Director), Columbia Pictures, 1959, Internet Movie Data Base.

Return to CooperToons Caricatures

Return to CooperToons Homepage

music.

music.