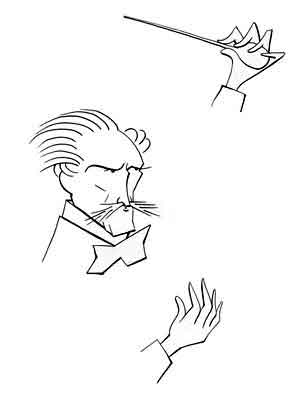

Richard and Cosima Wagner

Die Zwei Grosse Jerken

Richard and Cosima

Die Jerken

For those who may be completely and entirely new to the life, times, and music of Richard Wagner, his name is pronounced VAHG-ner. Articulating his name as the American WAG-ner will send your music teacher into spittle-flinging diatribes. And strictly speaking, his first name should be pronounced as ree-KAHRD, but it's OK at least for English speakers to use the Anglicized RIH-cherd.

Richard produced some of the greatest and yes, iconic music in history. His operas are arguably the most popular ever written, and he, rare among operatic composers, wrote both the music and the words. Other composers - and we include Handel, Mozart, Beethoven, Verdi, Britten, and Bernstein - always had someone else write the lyrics.

Perhaps the true test of Richard's greatness is that his music has reached the highest pinnacle (or if you prefer, descended to the lowest depths) of being used repeatedly for the background music for motion pictures and television shows. Even if the listeners don't know the actual operas or the names of the songs, they will recognize passages from Rienzi, the Flying Dutchman, Tannhäuser, The Valkyrie, Lohengrin, and Siegfried.

Too bad Richard was such a jerk.

What? Richard Wagner? A jerk?

Yes. Richard was a jerk.

Explain yourself, please.

OK, but first, a little about Richard himself. Richard was born May 22, 1813 in the German state of Saxony and in the Jewish section of Leipzig called the Brül. At that time Saxony had been invaded by Napoleon, and Leipzig was occupied by the French.

Richard's mom was the former Johanna Rosine Pätz. That much we're sure of. And his father was Carl Friedrich Wilhelm Wagner, a police official who had a strong interest and many friends in the arts, music, and the theater.

Or rather Richard's nominal father was Carl Friedrich. You see, Carl Friedrich died only six months after Richard was born, and Johanna almost immediately began living with a (wink, wink) family friend named Ludwig Geyer. Ludwig was a portrait artist as well as an actor and playwright.

But the haste of Johanna setting up housekeeping with Ludwig has led many to speculate that - or at least wonder if - Ludwig was actually the young Richard's real father. After all, Johanna was eight years younger than her first husband and Ludwig, a good looking man, was a year her junior.

Is all the scurrilous innuendo true? Well, you can argue no. After all, if you look at the letters Ludwig wrote to Johanna before they were married, they are rather restrained. He even uses the formal pronoun Sie when addressing her, rather than the du which you use when addressing intimate friends, children, and dogs and cats. For his part, Richard himself was never sure about the matter. Years later when a friend asked if Ludwig was his real father, Richard replied he didn't think so.

On the other hand, there are several very interesting (as Artie Johnson might have said) pieces of information that leads us to believe he was.

First, Carl Friedrich himself had been frequently away from home, and one story is he was sporting about with a young actress. If so, Johanna may have felt no qualms about inviting the family's good friend over to - ah - "drop in" so to speak.

Next, the fact that Richard's birth was not officially registered for five months - the other Wagner kids were registered in a few days - is taken by some Wagner scholars as an indication that Carl Friedrich initially refused to acknowledge the young Richard as his son. Certainly such delay is not what we expect of a proud father.

A related issue is that all the other kids born while Carl Friedrich and and Johanna were married always used the surname "Wagner". Richard, though and certainly at his mother's behest, went by the name Geyer. He only switched to "Wagner" when he was fifteen.

We also learn that Ludwig had married Johanna as soon as it was legally possible - nine months after the death of Carl Friedrich. They would have married sooner since Richard's younger sister, Eva, was born six months after the wedding. But the nine month hiatus was the law and was supposed to insure that everyone could be certain of any latent paternity. That we are still debating who Richard's real father was two hundred years later shows us the law wasn't perfect.

Also from the first Ludwig had a particularly warm relationship with young Richard, calling him his "Little Cossack". That is, he had a warm relationship with the boy as long as you overlook the story that Ludwig would sometimes thrash the kid with a bullwhip. We do know, though, that Ludwig would take the youngster along to his rehearsals and even get him bit parts in the plays. Very unusual when there was a mom at home to take care of the kids.

But most tellingly, as soon as Johanna had recovered from the birth and was well enough to travel, she up and left Carl Friedrich at Leipzig and traveled to Teplitz in Bohemia where Ludwig just happened to be performing. Although not specifically documented, it's pretty much accepted that she took the infant Richard with her. This trip was, we want to point out, in the middle of the Napoleonic Wars, and she and Richard traveled alone. Clearly there was something - ah - special with Johanna and Ludwig and Richard.

So in the end you can't have all that smoke without a little fire, and despite many authors opting for caution and saying it is "possible" that Ludwig was Richard's real father, we can be forgiven if we believe that he was. "Geyer" we should point out was a fairly common name among German Jewish families. So although it is not likely that Richard was of Jewish descent - modern scholarship has checked out Richard's and Ludwig's family trees pretty carefully - we can't rule it out.

In any case, soon after the marriage, Johanna, Ludwig, and the kids moved to Dresden. Two of Johanna's children had died when they were young, but the other seven grew to adulthood. Eventually the marriage of Ludwig and Johanna bumped up the number of Kinder in the household to a dozen. Most of the kids showed talent and worked industriously at their studies. But not, it seems, did Richard.

Figuring out exactly where Richard was educated and where he actually was living during his childhood can be confusing, and you have to sift through various biographies to get the whole picture. The Geyer/Wagner household was artistic but not always congenial to Richard, who was headstrong, cantankerous, and overly sensitive. Although he did develop a bond with his older sister Rosalie, he never felt his mother gave him any real affection. But after raising twelve kids - not an unusual brood size up to the twentieth century - perhaps we can forgive Johanna when she found her youngest son was a handful.

Certainly it seems Johanna didn't want the kid around, As soon as Richard reached school age (seven) she shipped him off to the Dresden suburb of Possendorf to a school which was run by a pastor named Christian Wentzel. There Richard took piano lessons, and although he showed talent (he could easily pick out songs by ear), he didn't really study very much and his playing was never more than adequate. But in a year he was summoned back home as Ludwig's health had begun to fail.

Ludwig died of tuberculosis in 1821. He was 42. There is the famous story that one day near the end Ludwig heard Richard playing the piano in the next room and wondered aloud if Richard might have talent for music after all. It's a good story although it sounds suspiciously like one of the after-the-fact-predictions-of-the-future. But who knows? Maybe it is true.

But once Ludwig died, again Johanna packed her son - now eight - off to live with Ludwig's older brother, Karl, who was a goldsmith. Some biographies state that Richard was living with his older brother, Carl Julius at this time. Actually both stories are true since Julius was an apprentice to Karl.

Richard was not interested in goldsmithing, of course. So after a year with Karl and Julius, he lived for a brief time with his Uncle Adolph (Carl Friedrich's brother) in Leipzig. Richard said that at Uncle Adolph's he had to sleep in a room festooned with large portraits of historical figures from Saxony. Trying to sleep under the portrait's eyes (which always seem to follow you around) was too much, and Richard would often wake up bathed in sweat surrounded by what he called the "ghostly apparitions".

By the end of 1822, the Wagner household had thinned down a bit - Richard's older brothers and sister Rosalie were now grown - and Richard returned to live with his mother at Dresden. He then entered the famous Kreuzschule associated with the Church of St. Nicholas. This too was a boarding school and Richard stayed behind when Johanna and the younger kids moved to Prague where Rosalie had an acting job. During the family's time away, Richard lived with a Dr. Richard Böme in a household that Richard found a bit chaotic.

But in 1827 Richard was back in Leipzig where Johanna and the kids, having returned from Prague, finally settled. There he attended the St. Nicholas school, and at this point Richard was actually interested in literature. He seemed to apply himself well enough and - if the story is true - he translated twelve books of the Oddysey into German. We must be forgiven if we question this anecdote but we can accept Richard's claim that he had decided to become a writer and poet. But then events happened that changed his mind once and for all.

In Mein Leben, his sometimes entertaining, often vague, and not always accurate autobiography, Richard said that back in Leipzig, he heard the works of the great composers of the time, particularly Carl Maria von Weber and Ludwig van Beethoven. Carl Maria had even been a visitor to the Wagner/Geyer household. So at age 15, Richard decided what the heck, he'd be a composer.

At this point, the life of Richard Wagner becomes almost unbelievable. With the patchiest of educations, Richard gets a job as a choirmaster, composes the successful opera Rienzi, has a smash hit with the Flying Dutchman, and becomes one of the most in-demand composers and conductors in Europe. He then writes the Ring Cycle and creates his own theater at Bayreuth which has been staging his operas ever since.

What the hey? How did that happen?

Well, let's get it straight. Richard did not just pick up a pen and started to compose. Once he decided to become a composer - this was around 1828 - the family agreed he could take private lessons in composition from a local teacher and composer, Christian Gottlieb Müller. For his own part Christian's compositions - which included operas and symphonies - aren't performed that much today, and when you find out one of his most widely available pieces is the Concertino for Bass Trombone and Orchestra, we're not particularly surprised. Richard would also transcribe orchestral scores for piano so he could play the music himself. So Richard not only got the piano adaptations for free, but he learned (somewhat in reverse) the principles of orchestration. But all in all Richard received pretty limited training.

Then in 1831, when Richard was 18, he decided he wanted to go to the University of Leipzig. After all, then as now there was a certain panache to being a college student. But given how rigorous entry requirements were (and are) for German universities we wonder how Richard, who had been a pretty rotten student, got in. One source tells us that he did not enroll through the normal channels. Instead Richard interviewed the Rector and convinced him that he, Richard, was well up to the U of L's standards. Possibly he also had a good recommendation from Christian. Then while attending the University - eins mehr we hear - Richard studied composition with the composer and teacher Theodor Weinlig.

However, that does not mean that he studied composition at the University. The biographies of Theodor - inevitably quite brief - mention that Theodor was the cantor - that is the church employee in charge of the music - at the St. Thomas Cathedral and its associated music school. We read nothing about him being a professor at the university. Also Richard was paying tuition directly to Theodor. We know this because we have a story that Theodor was so impressed with Richard's compositions that after a while he declined further payment.

So in the end we have to conclude that Richard's status as a - quote - "student" - unquote - at the University of Leipzig was pretty informal. He may not have been doing much more than hanging out with other students, drinking, gambling, and discussing the best way (as do all students) of changing the world for the better. But as far as his compositional studies go, we have to conclude he was actually a private student of Theodor, and he was a university student mostly in his own mind.

In any case, Theodor, professor or no, was surprised at his student's talent. Although Richard didn't have so-called "perfect" pitch (but neither did Franz Schubert or Leonard Bernstein), the young man had a natural gift for composition. Here we learn something about Richard. If he was interested in something, he learned incredibly rapidly and would willingly put in long hours of hard work.

Under Theodor's tutelage, Richard wrote his first compositions, and with Theodor's support they got public exposure. Richard wrote two overtures that were performed in Leipzig, and he composed a very non-Wagnerian sounding Piano Sonata in B-Flat Major. This last work was soon published, thus becoming Richard's Opus No. 1. He also wrote his first (and only) complete symphony, Symphony in C which really isn't bad, especially for a kid who was just barely 19. This is, by the way, the same age as Dmitri Shostakovich (who did have perfect pitch) when he wrote his Symphony Number 1 in F Minor. True you hear a lot of Beethoven in the Symphony in C, but you also get the beginning of that lush Wagnerian sound.

Lenny

Neither He nor Richard

At this point, we now learn that with these early successes, Richard's older brother Albert, who was a singer and theater director, helped Richard land a job as the choirmaster - that is Richard coached and rehearsed the singers - at a theater in Würzburg, a good sized town about 60 miles northwest of Nuremberg. That Albert helped his younger brother land the job is true enough, but we also need to mention Richard's sister, Rosalie. It was Rosalie, more than anyone else, who helped her younger brother make the transition from precocious (and private) composition student to practicing composer.

Now while Richard was growing up and goofing off, Rosalie had become one of the best known and respected actresses in Germany. Because of her fame and drawing power she had clout with theater owners. She commanded large fees, and because she had the best job of the family, she called the shots on how to direct Richard's aspirations.

Mitya

Both He and Richard

To give her younger brother something to do, Rosalie encouraged him to write pieces suitable for theatrical performances. These songs - sometimes called "overtures" even though the actual play wasn't an opera - were used for warming up the audience. No matter how ridiculous or silly they were, all plays of the time began with an overture. So when she appeared in a production, Rosalie would make sure that some of Richard's songs were played. His music became popular, and Richard was soon seen as the up-and-coming young composer.

So in the end Richard became one of the greatest composers in history by having the right teacher, a big sister with lots of clout, and a brother with connections. And of course, Richard had talent.

It was now 1833 and Richard jumped into his job at Würzburg with élan. The managers not only saw that Richard could coach the singers, but he could also conduct the orchestra, rescore the parts, and even write extra music if they needed it. And it was in Würzburg in 1834 that Richard first conducted an opera, Mozart's Don Giovanni. And it was also at Würzburg that Richard completed his own fledgling operas. The first was The Fairies, which wasn't performed during his lifetime, as well as Forbidden Love which unfortunately was.

Richard's enthusiasm for his job made him popular with the singers and musicians (he tells us so himself). However there were a few glitches. Debt collectors began showing up at the theater asking if Richard was around. It seems that Richard had already developed the notion that he should live as he wanted to, not as he could. A composer and artist of his ability deserved and by right a lifestyle (and its accoutrements) not needed by the rank and file. Part of the - quote - "necessities" - unquote - were expensive satin underwear that would help ameliorate the irritation of his unusually sensitive skin. Or that's why Richard said he wore them.

Naturally having creditors pounding at the door of the theater caused Richard and the company some embarrassment. It also delighted Richard's growing number of enemies. So after a year at Würzburg, Richard - or his employers - felt it expedient for the talented young man to look for other opportunities. This he did, and his next job was as the music director of a small theatrical company owned by impressario Heinrich Bethmann. This was in Magdeburg about 225 miles north and a bit east of Würzburg.

It was at Magdeburg that Richard met a young actress and singer, Christine Planer. Called Minna by her friends, the evidence from paintings and photographs is that she was a pretty young woman. But like many actresses she was kind of a free spirit. We read that when Minna met Richard she had been taking care of her - quote - "younger sister" - unquote - Natalie, who was actually Minna's daughter. Minna, of course, had never been married.

Still Minna and Richard themselves got married on November 24, 1836. By then they had moved once again. Although at Marburg, Richard was able to stage and conduct the opening and closing performance (they were the same) of his opera Forbidden Love, the theater itself had closed down. Yet once more landing on his feet, Richard got a job as a musical director, this time in Königsberg. This was not the modern day Königsberg just a short distance north of Würzburg, but the present day Kaliningrad in Russia. This was the Old Königsberg, then the capital city of Prussia, and it lay on the edge of the Baltic Sea.

The Königsberg gig ended in 1838 but by then Richard was the conductor of an opera company in Riga. Riga, now the captial of modern day Lavtia, was at that time an important port in the Russian Empire. There Richard and Minna hoped they would be safe from the German bill collectors who had been hounding them.

Now a lot of people know that Richard had girlfriends even after he got married. Sometimes these were pretty ladies that he met as part of his job. But others were the wives of friends who helped him further his career. This tendency of Richard's to dally with the ladies of his benefactors is one of the reasons why some people think he was a jerk.

But it isn't quite as well known that a few weeks after their marriage, Minna began to dally a bit herself. In some accounts we read she ran off with a dashing young army officer. Others say it was a promising young businessman. Then some stories say the officer or businessman soon dumped Minna, and so she returned teary-eyed to Richard. Others tell us Richard went and fetched Minna back. Regardless of what actually happened, we can be sure this episode soured Richard on Traditional German Family Values. As far as he was concerned, theirs was now an open marriage - or at least it was for him.

At Riga Richard began working on another opera, Rienzi, the Last of the Tribunes, which was based on the novel of the same name by the English author, Edward Bulwer-Lytton. But even in Russia Richard had liked to live well, and once more his creditors began closing in. Knowing that Richard and Minna would likely just pull up stakes and leave town, the creditors managed to have the passports of the wayward duo confiscated. There appeared to be no way out.

Or almost no way out. On July 9, 1839, with the aid of a wealthy art patron named Abraham Möller, Richard and Minna and their Newfoundland dog, Robber, snuck out in the dark of night. They literally made a dash across the fields through the heavily guarded border and made it to Prussia.

With creditors from Germany and Russia now hard on their heels, Minna and Richard decided they had to really get away. Germany after all wasn't that big - it's about midway in area between Montana and New Mexico - and with rail transport facilitating travel there was really no safe place left for Richard and Minna to hide.

So they took a ship, the Thesis, at Pilau and headed for England. On the way they encountered three storms and lost much of their luggage. The voyage usually took one week but this time it took three. Finally they landed, worn out and exhausted, in London. But at least Richard now had the idea for the Flying Dutchman.

Two people on Richard's must-meet list were Sir George Smart, the famous British conductor, and Edward Bulwer-Lytton, who we mentioned had written the novel Rienzi, the Last of the Tribunes that Richard had been adapting as an opera. But Edward's greatest claim to fame is that he began his novel Paul Clifford with the immortal words "It was a dark and stormy night." To his disappointment when Richard came a-knocking, he was informed both men were out of town although they probably were not.

Not being able to establish professional contacts in London and not speaking any English, Richard, Minna, and Robber headed to Paris after only a week. Here they met Giacomo Meyerbeer, who at that time was probably the most popular living operatic composer. Richard showed up at Giacomo's home and read him the libretto for Rienzi. Normally we would expect Giacomo would have listened politely, made condescending comments, and sent Richard on his way. This he did, but later events show us that Richard - and Rienzi - had made a good impression.

It was on this (first) sojourn in Paris in 1840 that Richard met one of the composer and pianist Franz Liszt. Franz was Richard's senior by only two years, but he was immensely more famous and popular.

Franz was, quite literally, the first rock star. His performances made men cheer and ladies swoon. Franz was also the first performer that the young ladies wanted to rip away his clothes. And as it was impractical for them to throw their underwear on stage, they tossed him roses. They would even pick up his discarded cigar butts and stick them down their bodices.

It takes a man of strong will to avoid the temptations of ladies literally hurling themselves at your feet. Franz, though of strong will, wasn't strong enough. His first main squeeze was Marie d'Agoult, and soon she and Franz found out they were going to have what in other circumstances would be described as a happy event. But since Marie was still married to the Count d'Agoult, she and Franz decided it was best to hightail it away. They did and their whoopee continued. Eventually Franz and Marie had three bundles of joy, Blandine, Cosima, and Daniela, and soon all three girls were shipped off to live with Grandmother Liszt. The kids didn't see their parents very often although they did keep in touch by correspondence.

Richard and Minna stayed in Paris for two years. The job market for wastrel conductors and profligate composers was fully subscribed, thank you, and Richard had to make do with freelance arranging of orchestral works for piano. This was not a lucrative occupation, and he and Minna borrowed money left and right (which they never repaid), pawned most of what they had, and once couldn't even afford to pay 7 francs postage due for the score of the Rule Britannia Overture that Richard left for the perusal of Sir George Smart. Without the required postage, the score went back to England and in the 20th century showed up in a storage trunk. Richard even spent some time in debtor's prison where he finished orchestrating Rienzi. He got out of jail when Minna borrowed money for his bail.

Robber, by the way, ran away and found a better home. A year later Richard caught sight of him on the street. But the pooch took one look at his former master and immediately turned tail and got away despite Richard's frantic efforts to catch him. At least, that's the way Richard told the story.

Well, what to do now? Richard was out of jail, but prospects still didn't look great. He could, of course, have decided to live within his means. But that would be too easy - and certainly not appropriate for a genius of his stature.

Instead Richard wrote to King Friedrich August II, the King of his old home of Saxony. Richard said that he thought Rienzi, his new opera, should be premiered in that country and particularly in Dresden, the capital city. That a king would pay attention to a letter from a debt ridden and largely unknown composer, conductor, and copyist seems amazing. But on the opera's merits (not to mention a recommendation from Giacomo Meyerbeer), Friedrich August sent Richard a reply that the Royal Saxon Opera would indeed stage the premier of Rienzi in October 1842.

But then came more good news. In Paris, Richard had also completed the Flying Dutchman and sent that score - unsolicited - to the prestigious Berlin Opera. It was also accepted. Again we have to give a nod that the music Richard wrote really was good.

So in 1842, Richard and Minna left Paris and headed off to Dresden. Rienzi was a success. Richard was now a famous composer with two hits to his name. So he decided to stick around Dresden.

At first as in Paris, Richard only had freelance work to do. But within a year his new-found fame had landed him the post of assistant Royal Kapellmeister, that is the #2 conductor for the king's own orchestra. Richard was now only one step away from being the real Kapellmeister, which was about as high as a composer and conductor could go in 19th century Europe. Best of all the jobs of Kapellmeister were intended to be permanent. Richard was now set for life as long as he didn't screw up.

Alas, he did. It was in Dresden that Richard made perhaps the biggest faux-pas of his life. And when he had to pull up stakes and clear out of Germany this time, it had nothing to do with debt. It was literally a matter of life or death.

First a little background is in order. In 1848, King Louis-Phillipe I of France, who had been throwing people in jail without trial and presiding over a country with a failing economy and increasing poverty, made it illegal to attend banquets. Banquets, he thought, served no useful purpose and were simply fanning the flames of the seditious rumblings of his ungrateful subjects.

Well, that was too much. I mean, arbitrary jailing of political enemies is one thing, but forbidding banquets? The citizens took to the streets and forced the abdication of Louis-Phillipe who fled to England. France then set up the second (out of a current five) Republics.

Inspired by the events in Paris, people throughout Europe were soon demanding written constitutions, limits on police power, trial by jury, freedom of speech and press, right to assemble, and representational government. After all, this sort of bleeding heart liberal stuff was working fine in England and America where everyone got along with either figurehead monarchs or none at all.

Richard, who always saw himself as a far left political liberal, joined in the revolutionary fervor. He started writing articles advocating democracy. Some were anonymous, others were signed. He also gave speeches at rallies, one delivered to a group called the Vaterlandverien or the Fatherland Association. He advocated one-man-one vote, establishment of elected assemblies, and abolition of aristocratic privileges. He even criticized the bad effects that having too much money had on people (yes, this was Richard talking).

Now most people think of artistic types as a bit flakey and will make allowances for their oddball behavior. So the Dresden authorities more or less ignored Richard's rants. However some of his friends privately advised him that if he kept up his revolutionary diatribes, he might, at the very least, lose his job. But always the contrarian, Richard continued writing articles and giving speeches.

At first Friedrich August, the King of Saxony, had actually played along with his subjects. He let the citizens write a constitution and set up an assembly. But by April 1849 he was fed up with the never ending brouhaha of starry eyed reformers like Richard Wagner. So Friedrich August tore up the constitution and abolished parliament.

On May 3, the city rose up in rebellion, and armed citizens barricaded the streets. Three days later the army moved in and massacred everyone. They shot down students and even threw rebels out of upper story windows. In two days everything was over.

Minna had already left town and was staying in Chemnitz, 50 miles to the west. Happily (for him) Richard managed to get away and join her. Naturally Minna was not pleased with her husband who had literally thrown away a well paid and cushy job just so he could play at being a revolutionary.

At this point Richard (leaving Minna in Chemnitz) managed to get to Wiemar where Franz Liszt was Kapellmeister and had recently staged the premiere of Richard's opera Lohengrin. There Richard learned the king of Saxony had charged him with treason. Normally Richard would have been safe in Wiemar as it was another country. But the trouble was Wiemar and Dresden had extradition treaties.

Franz gave Richard money enough for his escape knowing darn well he would never get repaid. He also had a friend, a Professor Widmann who taught at the University of Jena, who gave Richard one of his old and expired passports. So traveling as Herr Professor Widmann, Richard managed to reach Lindau on the shores of Lake Constance just across from Switzerland. At Lindau his passport was taken away for an overnight inspection to make sure it was in order. It wasn't since, as you remember, it was out of date. But amazingly the next day the officials smilingly returned the passport and wished "Professor Widmann" godspeed to Switzerland.

Franz

A Friend

We need to mention that Richard had never actually advocated overthrowing the kings. Instead, he felt the monarchs should be incorporated into the new governments with the rank of First Citizen. So some of Richard's friends thought the king had been a bit harsh and began working on Richard's behalf. But each time they asked the king for a pardon, he responded by re-issuing the arrest warrant. Like it or not, Richard was not going back to Germany anytime soon.

Minna, although now thoroughly fed up with her feckless husband, joined him in Zürich with their new dog and parrot. She immediately began chewing Richard out, and Richard later wrote he had more joy at seeing the dog and bird than Minna.

Richard and Minna lived in Zürich from 1849 to 1858. Richard continued to work and compose, sponge off his wealthy friends, and get into debt. He probably would have stayed longer except Minna found (and read) a letter to one of his girlfriends, Mathilde Wesendonck. Mathilde was a well-known poet whose poems Richard had been putting to music.

Whether there was any whoopee between Mathilde and Richard we don't know. But we should also mention that Otto, Mathilde's husband, had been letting the Wagners stay at the Wesendonck home rent and board free. For her part, Minna was not pleased when she read her husband's love letter to their hostess. She raised such a scene that Richard not only left the house but Zürich as well.

Well, there was only one option left and that was Paris. Not only did Richard now have friends and opportunities there, but being the generous man he was, he would give the Parisians another chance to recognize his genius and give him enough money to live lavishly and to pay back the 20,000 thalers he owed the various creditors (Richard's salary in Dresden had been about 1500 thalers a year). So in 1849, to Paris he went.

Richard took a lavish apartment and hired a staff of servants including a personal valet. Minna soon joined him, and far from being impressed with her husband's confidence in his future earning power, she went into spittle flinging diatribes that he was driving them to ruin. They had daily shouting matches and Minna once more returned to Dresden where Richard couldn't follow.

Perhaps even to Richard's surprise, the Parisians did indeed welcome him as a genius. He conducted concerts which were enthusiastically received and made friends with the highest levels of Parisian society. The King of France, Louis Napoleon Bonaparte (the nephew of the famous Napoleon), even commanded a production of Tanhäuser.

So things were looking up, non?

Well, non. The production was a disaster. It seems that in Paris you had to have a ballet in the second act of any opera. This was because the members of the Jockey Club - a fancy and influential gentlemen's organization - had a lot of girlfriends in the ballet company, and naturally the men liked to see their girls on stage. Also the Jockey Club ate their dinners late and would only show up for the second act. Richard agreed to include a ballet, but said he'd put it in Act I. The members of the Jockey Club could show up on time for a change.

Tanhäuser opened on May 13. In attendance was the King and his wife, Princess Eugéne (who, although a pretty woman, had - as Karl Marx once mentioned - the "indelicate" complaint of being passionately addicted to farting). Also attending were the members of the Jockey Club who did indeed show up on time. But rather than watch their girlfriends pirouette en pointe, they catcalled and jeered throughout the show. They also showed up for the second performance, this time fortified with dog whistles. There was more of the same for the third performance and the production closed.

Well, that was that. Richard left Paris in 1851 and never returned. But the good news was that all German states - except Saxony - had decided Richard could return without fear of arrest.

Richard continued to make money by conducting what were called benefit concerts. Today this term means a concert put on for some charitable event. But before the twentieth century, the beneficiary at a benefit concert was usually the performer.

Richard's concerts were popular with the public although the critics usually trashed his technique and selections. One characteristic of Richard's baton work was he conducted with much rubato - that is varying the beat. This was not, we should say, because he couldn't keep time, but it was simply a popular style of the era.

Despite his popularity and the money he made, Richard continued to fall further and further in debt. It wasn't that he didn't make good money. He just lived - as one friend said - like a lord. He also behaved like a kid. As as soon as he had money he would blow it. Despite his fame, by the 1860's he was still having to pull up stakes and move from one town to another to avoid his creditors.

Finally Richard ended up in Stuttgart, and this time he was stuck. He now had virtually no money, and any conducting opportunities had dried up. No impresario was willing to take him on since any money earned would be claimed by Richard's creditors. Debtors' prison was once more a real possibility. About the only thing that could save Richard was the fantasy scenario where some rich monarch would invite him to come live in his kingdom at government expense, would pay off all his debts, and then build a special theater solely for the staging of Wagnerian operas.

Which is exactly what happened.

When he was a kid growing up in Bavaria, Ludwig II had become infatuated with Richard's operas. He became king in 1864 at age 18 and quickly dispatched his personal secretary, Franz von Pfistermeister (that's his real name, not a misprint), to track down the now elusive composer. The men met at Stuttgart and Richard was flabbergasted to learn that King Ludwig would indeed settle his debts, give him a spacious home, and let him have all the resources he needed to fulfill his artistic ambitions. Among these plans was the creation of a new theater dedicated to his own operas. Naturally Richard didn't have to be asked twice.

This is now a good point to introduce another of the important people in Richard's life and legacy. When Richard first met Franz Liszt in 1840, he didn't meet any of Franz's family. But in 1853 Richard met the Liszt kids, including the 15 year old Cosima. Tall, skinny, and gangly and (we must admit it) not a classic beauty, she made little impression on the 40 year old composer.

Cosima did not grow up in a happy home - or rather homes. Eventually Marie and Franz parted ways and Franz's new girlfriend, Caroline Wittgenstein, sent the girls to her old governess, a no-nonsense martinet named Madame Patersi. But when Cosima was 17 she and her sisters were packed off to Berlin and lived with a friend of Franz's, Franziska Elisabeth von Bülow. Franziska was a bit more congenial that Madame Patersi, but the girls still weren't happy.

Franziska, though, had a son, Hans, who was 25 when the girls moved in. He had studied piano with Franz and had also made a name for himself as a conductor. On August 18, 1857, Hans and the now 19 year old Cosima married.

Hans, we should point out, was a true virtuoso, both as a pianist and a conductor. As did (and do) many people, he loved Richard's music. He had been at the premier of Lohengrin which Franz had conducted, and as a boy growing up in Dresden, he had attended performances where Richard himself had taken the podium.

Hans had even met Richard, traveling to Zürich just for that purpose. As he often did, Richard warmly received the younger man and was impressed with his playing. Richard then - and we have to admit that Richard could be very kind to young musicians - helped Hans get a conducting job at Zürich. Sadly Hans had a terrible personality, didn't get along with the musicians, and he lasted at Zürich only a few months.

Eventually Hans landed the post of Kapellmeister at Munich. Although he didn't particularly like the place (he once wrote that the people in Munich were schweinehunde), he had become a true champion of Richard's music, and he had conducted the premiers of Tristan and Isolde and Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. Munich, by the way, just happens to be the capital of Bavaria, whose king, we should remember was Ludwig II.

The marriage of Cosima and Hans was - like her childhood - not particularly happy. Then in 1857, accompanied by Hans, Cosima met Richard for the second time. Richard and Minna were still together then, and Cosima thought Richard was a jerk. He was egocentric and didn't treat Minna the way Cosima thought a wife deserved.

In 1863, she and Richard met again in Berlin. Cosima now found Richard quite congenial and not a jerk at all. Then during a carriage ride she and Richard reached, well, an "understanding". But for now they couldn't do much. Richard was strapped for cash, and he was still married to Minna and she to Hans.

Within a year, though, Richard was living in Bavaria and being supported by King Ludwig. He then wrote to Cosima and Hans asking his friends to come visit. Alas, Hans couldn't make it just then, but Cosima traveled to Richard's now spacious home. Nine months later she had a daughter named Isolde of whom no one - not even Cosima - really knew who the father was.

Richard and Cosima made an odd pair, not the least from their contrasting physiques. People who knew him commented on Richard's short stature. Now his height is usually given as 5' 5". But you'll also read 5' 5" was the average height for a nineteenth century European male. But if the average male was 5' 5", and Richard was 5' 5" why did people say he was so short?

Well, not everyone says Richard was 5' 5". One Wagner authority mentions that Richard was probably between 5' 1" and 5' 3". That makes a lot more sense. However, if you don't want Richard to be such a shrimp you can dispute the modern claims that people were 4 inches or more shorter back then than we are today. Some studies on skeletons as long ago as the 18th century have shown that the differences between them and us may have been more like two inches rather than four. So maybe Richard was 5' 3 1/2" in a land of 5' 7" giants.

The issue of their comparative statures is made more confusing by descriptions of Cosima. People commented on how tall she was. But that could also be in reference to her height compared to other ladies of the time. Matters aren't resolved by the fact that most of the time Cosima and Richard are photographed with one of them standing and the other sitting, or both of them sitting and Cosima slouching. There is one photo of the family standing on the front steps of their house and Cosima is no taller (and a heck of a lot thinner) than Richard. But she is bending her head forward slightly and Richard's wearing a hat. We can also see that Richard is standing on one of the steps but Cosima's legs are blocked by her daughter, Daniela. We can hear the photographer telling Cosima to take a step down.

Ludwig II

Richard didn't have to be asked twice

Despite his now firm liaison with Cosima, Richard still felt duty bound to support Minna. Even when he and Cosima definitely began producing children without assistance from Hans, he felt he could not abandon Minna.

Then in 1866, Minna died. She was 56, which was not a particularly young age for a lady of that time. Richard could now marry Cosima - except for one thing.

Yep. Except for Hans. But Richard and Cosima took care of that problem in a most expeditious manner. By 1866 Cosima was expecting another kid - who would be named Eva - and this time there was no doubt who the father was. Accepting the inevitable, Hans agreed to a divorce. So Richard and Cosima finally married in 1870 - a year after their son Siegfried was born.

We now have to step back for a moment. Originally Ludwig wanted the Wagner Festivals to be held in Munich, the Bavarian capital. But after exploring other alternatives, the conductor Hans Richter suggested the provincial town of Bayreuth (pronounced buy-ROIT) instead. It had a theater that should meet the demands of the typical Wagner opera. Bayreuth was fine with Richard, although he found the theater inadequate and still wanted to build a new one.

There were still some problems and yes, these were about the money. When Ludwig first agreed to pay off Richard's debts, he had no idea what he was getting into. After a while Richard had siphoned off so much cash that the king ran short of paper money. This didn't phase Cosima. She just showed up at the treasury in her carriage and hauled off bags of coins.

Soon Ludwig's subjects began murmuring that it would be better to have a king who kept the traditional ballerina rather than a self-centered and high-living composer. And although it's great to be king, if you want to build a theater it still costs money and the royal coffers became even thinner once Ludwig began other building projects.

But things probably wouldn't have gotten that bad except that Richard began to butt his nose into politics, suggesting to Ludwig who should be in charge of this-or-that office. Eventually feelings were so strong against Richard that the prime minister privately told Ludwig that Richard's presence was actually destabilizing the government. Although Ludwig was young, he was no fool. But it was still with real sadness when he told Richard it would be best for him to leave Bavaria. In December of 1865, Richard did.

Richard's absence, of course, did not preclude accepting handouts from the king. Neither did Richard abandon his plans for the theater at Bayreuth, and he was sure eventually he could return to Bavaria.

So it was in 1872 that with much pomp and fanfare Richard laid the cornerstone for the theater at Bayreuth. But a single stone does not a theater make, and trying to arrange private financing for actually putting the structure up didn't pan out. Finally in 1874, Ludwig stepped in and was able to arrange a loan, yes a loan of 216,152.42 marks. This was a huge sum at the time, and it wasn't paid back in full until 1906.

The theater, the Bayreuth Festspielhaus, was completed in 1876, and although the Wagner Festivals got off to a financially rocky start - the second Festival wasn't until 1882 - they eventually achieved not only artistic success, but finally ended up in the black. So living at Bayreuth in the Haus Wahnfried, Richard and Cosima lived, more or less, happily ever after.

OK. We now have read "a little" about Richard. So why was he such a jerk?

What puts Richard in the category of high jerkdom was that one day in the late 1840's, he sat down and wrote a draft of what has to be one of most asinine articles ever penned. This - quote - "article" - unquote - was finally published in 1850 and has insured that Richard's music - which few deny is among the most important and popular in history - will always - that's always - be connected with the politics and philosophy of the man who is universally regarded as the worst tyrant and murderer in history.

The article is of course the notorious essay Das Judenthum in der Musik or as it's often translated into English, Jewry in Music. Appearing in September, 1850 in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, it is an entirely banal and ridiculous diatribe in the guise of a reasoned philosophical treatise. It is singularly unpleasant to read, not only because of its message, but because of its puerile prose.

Of course, today no one of education or intelligence would accept Richard's ideas on race and religion whatever the race or religion. But Richard's critics see the essay as what led to an increase in anti-Semitism in Europe in the late 1800's. Worse, some even see his beliefs as a direct harbinger of those of the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, the NSDAP, that is, the Nazis.

But others maintain it's absurd to look at Richard only through the eyes of those who grossly perverted his views half a century after his death. They point out that the Wagners had many Jewish friends and Richard's favorite conductor during his final years, Hermann Levi, was not only Jewish but Hermann's father was a rabbi. Richard also supported young Jewish musicians, teaching them, and even bringing them into his home. Once he joked to Cosima that their home was becoming a synagogue. Some people claim Richard wasn't really anti-Semitic at all.

This last position is really hard to defend. In Das Judenthum in der Musik Richard writes specifically about vindicating the Germans' "involuntary repellence" of the "nature and personality of the Jews" and that Jewish citizens have something "disagreeably foreign" no matter what country they live in. He denies the God of the Christian is the same as the God of the Jew "who as everyone knows, has a God all to himself". He also goes on to vilify German-Jewish composers, not only Giacomo Meyerbeer - who you'll remember recommended Rienzi to the King of Saxony - but even the ever popular Felix Mendelssohn. Richard is also clearly advocating that Jewish people are a separate race, not just practitioners of a different religion since Meyerbeer, although born to an important Jewish family, was actually a practicing Lutheran. Mendelssohn's immediate family, too, had been baptized as Protestants, and Felix had not even been circumcised. As for Richard himself, he wrote to Franz Liszt shortly after the essay appeared that "I have cherished a long repressed resentment about this Jew money-world, and this hatred is as necessary to my nature as gall is to blood".

Now among those who admit Richard was anti-Semitic - which is most people - are those who say that his views were simply typical for the time. Some say that if you weren't Jewish in the 19th century then you would have likely been anti-Semitic.

Neither view is correct. As soon as it was published, Das Judenthum in der Musik was recognized as extreme. When the essay appeared, the entire faculty of the Leipzig Conservatory demanded the resignation of the editor of the magazine, Franz Brendel, who was himself also on the faculty. Among those who were nonplussed by the essay was none other than Richard's wife, Minna. How could Richard write such things about a group of people who had contributed so much to Germany and had provided them personally with much professional and financial support?

But others say what about people like Frederic Chopin? Or Franz Liszt? Don't historians point out that both of these men were anti-Semitic? And yet no one debates whether we should play their music.

Actually no one denies there was (and is) rampart anti-Semitism. And yes, in his letters, Frederic would gripe about his publishers (who were indeed Jewish) with stereotyped remarks. But such comments are few and far between and weren't something that permeated his personality.

As far as Franz's opinions on race and religion, we have his own words. He said flat out he was not anti-Semitic and that he had respect for all decent people. Supposedly what were his anti-Semitic comments came from letters that didn't show up until 1945 and are now roundly considered to be forgeries. But most of all to show that anti-Semitism wasn't universal we can turn to a letter that Ludwig II wrote to Richard.

We mentioned in Richard's later years, he had high regard for the Jewish conductor Hermann Levi. But Richard had nevertheless expressed reservations about Hermann conducting Parsifal which he felt was the most "Christian" of his operas. He even suggested - although it may have been in jest - that Herman should first undergo baptism. Finally Richard decided Hermann would indeed conduct the premiere, no strings attached.

On October 11, 1881 and after Ludwig learned of Richard's decision, he wrote the composer saying "That my beloved friend draws no distinction between Christians and Jews in performing his great and hallowed work is all to the good. Nothing is more repellent and unedifying than such arguments. People are basically all brothers, in spite of their denominational differences." So not only did Ludwig see Judaism as a religion, not a race, the idea that if you were not Jewish in Wagner's time, you were also anti-Semitic is clearly not true.

But as far as Das Judenthum in der Musik goes, we'll get right to the point. The whole essay is bad enough but the one sentence that really causes Richard so much grief is:

Aber bedenkt, daß nur Eines eure Erlösung von dem auf euch lastenden Fluche sein kann: die Erlösung Ahasvers - der Untergang!

Or in English fortified by two years of college German

But think, that your one (and) only redemption can be the redemption of Ahasuerus - Untergang.

Now the reference to Ahasuerus is a bit difficult. Ahasuerus is the biblical name for the Persian king Xerses whom the Greeks thumped at Thermopylae. The reference, though, is certainly about the legend of the Wandering Jew who was supposed to wander the Earth until the second coming.

But the big problem is trying to determine what Richard actually meant by the German word Untergang. Literally - as almost anyone can tell - this means Going Under.

Now here we have left Untergang in the German. But what did Richard actually mean? Well Untergang can mean - according to German-English dictionaries - sinking, setting, decline, end, and downfall. So it is possible that by also citing the passages where Richard talks about the Germans and its Jewish citizens being united as one, you can interpret Untergang as Richard advocating that the Jewish Germans should adopt German culture and give up their own. That is, they should accept assimilation.

But there is a bit more chilling interpretation. You can also translate Untergang as destruction, death, and yes, even as extinction.

Is this really what Richard meant?

Well, he never said so and the consensus is that his friendship with many Jews belies such extreme interpretation. And he later wrote essays that he claimed proved he had nothing against the Jews.

Ignoring the fact that some people think his later essays are worse than Das Judenthum in der Musik, we also know that in private conversation, Richard could let his guard down. Since Cosima kept voluminous diaries which have been published, we can find things that Richard said in the privacy of his own home.

Particularly worrisome are comments he made in 1881 when there were Jewish pogroms in Russia, and many Jews were killed. Cosima recorded that Richard remarked, "That is the only way it can be done - by throwing these people out and thrashing them." Then once Cosima mentioned Richard snorted as a "drastic joke" that the Jews should be burned at a performance of Nathan the Wise, a play about religious tolerance.

Of course, Richard's supporters can point out that we only have what Cosima said Richard said, not actually what he said. And since we read that Cosima was always making snide anti-Jewish comments, maybe what we're reading is Cosima's opinions more than Richard's. Or perhaps what Richard said were drastic jokes. That is, examples of "sick" humor that most people at one time or another indulge in.

But we have to wonder. Just how is it possible for two people to read what Richard wrote and reach completely opposite conclusions of what he meant and what he believed? That, though, isn't really hard to figure out.

First, when you try to "explain" Richard's views you are by definition trying to find a coherent and consistent line of thought in his essays and attempting to reconcile apparent contradictions in what he wrote. The point is there is no consistent line of thought in his essays and you cannot reconcile apparent contradictions in what he wrote. Richard may have been a great composer, but he was a rotten philosopher.

Also what few (if any) commentators mention is that Richard's essays are just quintessential examples of bad writing. His articles are full of - to use George Orwell's wording - pretentious diction and meaningless words, and there are whole passages that are almost entirely devoid of meaning. You'll get stuff like "Pride is the soul of the truthful", "Honor itself is the sum of all personal worth", and "Our object merely bids us linger with the purest and noblest to realize its overwhelming difference from the less". He did not write "Awe is but the product of an uncomprehending mind". After all that makes sense.

Because Richard's writing is so bad, you can easily pick and choose - and assign your own meaning - to whatever you want. Some defenders of Richard tell us - as stated on one popular website - that he makes no claim that there is a special "Germanic" race and instead says we must "look past the notion of race to focus on human qualities".

But you'll also notice that Richard seems to have had trouble distinguishing reality and fiction (he cites myths about Hercules and Siegfried to bolster his views), muses that evolution could only apply to non-white races, speaks about "Aryan" virtues, and blatantly talks about degeneration of "white" blood by - and this is a quote - "former cannibals now trained to be the business-agents of Society". Soddy, folks, Richard's views were anti-Semitic, racist, and even in his own time, extreme.

We have to ask. Did Richard believe all that scheiße? Was he going nuts?

Well, by the early 1880's Richard was not a well man. He was in his late 60's - quite elderly for the time - overweight and suffering from digestive "spells". He and his physicians thought his problems were due to excessive flatulence and gas buildup, but probably were from unstable angina.

After the 1882 Festival, Richard and his family took a vacation to Venice. Taking rooms in the Palazzo Vendramin Calergi on the Grand Canal, on February 13, 1883 he was sitting at his desk when he suffered a heart attack. He called for help, and Cosima managed to get him to a couch where his watch fell to the floor. His last words were "Oh, my watch!"

Cosima stayed by Richard's side for 24 hours and was so distraught - refusing to eat for days - that her friends and family feared or her life. Even Hans, her ex-husband, wrote her a kind supportive note.

Richard's coffin was loaded onto a train and taken to Bayreuth. He was buried in a private - although well-attended - funeral. Two of his pallbearers were Jewish.

Throughout Richard's final years he had the unflinching support of Cosima. If Richard thought he could do no wrong and what he wrote was Gospel, then Cosima agreed ten fold. After Richard died she took over the running of the Bayreuth Festivals and made sure the operas were performed to Richard's specifications. We do have recordings from Bayreuth made during her lifetime and so have some idea of how Richard wanted his works to sound.

The complex and massive stage settings that Richard demanded were not without their problems. For the first Bayreuth performance of Siegfried the dragon puppet had been made in London. Because it was so large they had to ship its parts in separate boxes. But the box with the neck had accidentally been sent - not to Bayreuth, Bavaria - but to Beirut the city in modern day Lebanon. On stage the improvised contraption looked pretty silly and when Siegfried slew the dragon the audience giggled. This they often do today and in fact, some of the other scenes in the operas have to be played for laughs.

As Cosima aged she, who was rather crotchety to begin with, got increasingly so. Once she sneezed and her granddaughter Maria said "Bless you, Grandmama!" to which Cosima replied, "How tasteless!" When another granddaughter asked one morning how she had slept, Cosima simply huffed, "I wouldn't ask such foolish questions." Definitely a grumpy grandma.

Cosima had never gotten along particularly well with her father - understandable since he had pretty much dumped her off with various governesses - and she didn't really want him around. But she did invite him to the 1886 Bayreuth Festival where he was promptly bedridden with pneumonia. How Cosima reacted depends on which biography you read. Some say she was simply not able to cope with her seriously ill father and so gave the appearance of indifference. Others write how she ignored the dying man, thinking the festival came first. Franz is buried in the Alter Friedhof Cemetery in a manner a bit fancier than Richard.

The year 1914 found Cosima waxing enthusiastic about the newly declared war as well as the pro-war essays written by her son-in-law, Houston Stewart Chamberlain. That Houston was an unabashed admirer of Richard Wagner and had written a highly laudatory biography of the composer had established his standing with Cosima. He was also a true believer in a master race and a virulent anti-Semite, although he did not, to be fair, advocate violence.

Two of Houston's greatest disappointments in life were he had been born in England and not in Germany and that he was not related to Richard Wagner. To correct the last of these faults and ameliorate the former, in 1905 he divorced his wife of 27 years, moved to Bayreuth, and in 1907 married Cosima's and Richard's daughter, Eva.

Houston was a prolific author and his most famous work was the Foundations of the Nineteenth Century. Written in a convoluted meandering style in bad need of an editor, the book was published in England under the prestigious imprimatur of the Bodley Head and became a best seller. Because Houston was able to put such a high-sounding educated veneer on racism, he more than anyone else made bigotry in general and anti-Semitism in particular acceptable among people who really should know better. If he still has a number of admirers today, then so does ... well, we don't want to get ahead of the story.

It wasn't until Germany and England went to war that Houston, now on the verge of 60, applied for and received German citizenship. For his - quote - "contributions" - unquote - to Germany Kaiser Wilhelm II awarded Houston the Iron Cross. Houston was also anti-Catholic, believed Jews were not really the same species as Germans, and argued that internal evidence of the Bible indicated Jesus wasn't Jewish. If the general consensus is that Cosima, like Richard, was a jerk, she was clearly surrounded by jerks.

Richard and Cosima's son Siegfried - by nature an easy going young man and completely the opposite of his bombastic namesake character of the Ring - became an assistant conductor at Bayreuth in 1893. He went on to write operas, works for orchestra, and vocal compositions - actually more stuff than his dad. Although many of Siegfried's works have been recorded and performed (and still are), none are in what we call the standard repertory.

By the turn of the century, Cosima's health began to decline, and in 1906 Siegfried took over running the Festivals. But Cosima was still healthy enough to worry about keeping the management of the Festivals within the family. She kept hoping that Siegfried would marry a nice fecund young lady and beget a lot of little Wagners who would carry on Richard's torch. Unfortunately even after he reached his mid-40's Siegfried was still single and clearly preferred masculine company.

Finally Cosima persuaded her recalcitrant son to marry Winifred Williams, a young Englishwoman who had been adopted by a German family. The couple did marry in 1915 and soon had four kids, one of whom, Verena, is still alive at this writing.

In 1923 an up-and-coming politician whose grandmother was the former Maria Anna Schicklgruber showed up at the Bayreuth Festival. Siegfried and Winifred received him in their parlor. It isn't known whether the politician's life-long gastronomical complaint known as meteorism (that once prompted a hostess to call to her servants "Open the windows quickly! It smells in here!") was evident. But when the politician departed, Winifred turned to her husband and said she thought he was the most magnetic man she had ever met. One author wrote that Siegfried laughed and said that as far as he was concerned the man was a charlatan. If so, it was a short lived opinion, and soon Siegfried was echoing his wife's sentiments that Adolf Hitler was the true soul of the German people.

A year later to help raise money for the Bayreuth Festival - which had become expensive after the post-war hyper-inflation hit Germany - Siegfried undertook a concert tour of America which he kept secret from his mother who by now wasn't a great fan of the United States. However, Siegfried's behavior (perhaps fueled by a bit too much to drink) was a shock to many. At public appearances, he would go into rants against Germany's democratic Wiemar Republic and take anti-Semitic swipes at musicians like Bruno Walter. Given that many of the prospective benefactors - and Wagner fans - were Jewish, it's no surprise that the hoped-for contributions dried up and Siegfried returned to Bayreuth with far flatter pockets than he had hoped for. If Cosima and Richard were jerks, so it seems like father, like mother, like son.

We don't know, of course, how Richard would have responded to Hitler's support. But we do know only one of Siegfried and Winifred's children became a staunch anti-Nazi. That was Friedelind, the #2 daughter. Friedelind, who didn't get along with her mother very well, left Germany in 1939. She soon moved to the United States where she denounced Hitler publicly and said her grandfather would never have supported him.

Did Hitler meet Cosima? Some stories say yes but Winifred (who lived until 1980) never mentioned anything about it. So probably not.

Arturo "Toscanono

(To the Musicians)

Cosima, although grudgingly tolerating at least some Jewish musicians and performers at the Festivals, definitely wanted Germans on stage and in the orchestra pit. It wasn't until after she died on April Fools' Day, 1930 that Siegfried brought in the Italian maestro Arturo Toscanini - whose tantrums and rantings in Italian soon had the performers dubbing him "Toscanono". Toscanini, we should remember, was a vehement anti-Fascist and refused later invitations to conduct at Bayreuth.

Four months after Cosima died, so did Siegfried. Some think this was because Siegfried was such a mama's boy that the loss of his mother was too much to bear. But actually it was a heart attack likely brought on by the stress and strain of preparing for the upcoming production of Tannhäuser.

After his stint in Landsberg Prison, Hitler avoided public appearances with the Wagners, afraid (so he said) that his presence might injure their reputation. He did pay visits in secret, though, sneaking in at night, often with Winifred - an enthusiastic motorwoman - personally picking him up in her car. But in 1933 Hitler became Reichschancellor and began taking time off to visit the Festivals in an official capacity.

Winifred continued to enthusiastically welcome her now long-time friend. They were on a first name basis, she calling him by his nickname "Wolf" and he addressing her as "Winnie". Their relationship was so cordial that some people mused they might get married. They didn't, of course, and besides, Siegfried's will stipulated that should Winifred remarry, she would lose management control of Bayreuth. The Festivals continued through the 1930's - although now so thoroughly politicized that most foreign visitors stayed away. They kept going during the war through 1944, often packed with soldiers recuperating from their wounds.

In her later years, Winifred sometimes expressed shock! shock! at the horrible events that happened - as she put it - during the "last part" of the war. She maintained she had always opposed the physical attacks of the Nazi's against the Jews, and we do have contemporary correspondence which confirm this claim. She also said she even interceded to get people freed from concentration camps - or at least people whose requests "seemed credible and also worthy of assistance".

Above all she stated she was never a member of the Nazi party and that her family's relation with Hitler had been purely a personal one based on the love of the music of Richard Wagner. Besides she doubted that Hitler himself really had anything to do with the really bad crimes of the Nazi's anyway. Not her dear Wolferl. It must have been those thugs like Göring and Himmler and Goebbels.

Siegfried and Winnie

She was shocked

Still the fact that she was recorded in 1943 saying she never stopped believing in Hitler and his National Socialist ideas and that she had stuck with him through thick and thin - not to mention that there are films of her giving the Nazi salute at Bayreuth - didn't help her standing with the post-War German government. Nor has it helped that later historians found that there had been a branch of the Flossenbürg concentration camp at Bayreuth and that Winifred had indeed been a long-time member of the Nazi Party. She joined on January 26, 1926 and given the party ID number 29349.

After the war Winifred was found guilty of furthering the Nazi cause, and although the prosecutor wanted her to spend six years in prison at hard labor, she was simply prohibited from involvement in post-war business or government responsibilities for two years. The leniency was due in part because Winifred had indeed saved some people from the concentration camps.

Winifred now realized she was a liability, and she turned the management of the Festivals over to her son, Wieland. The Festivals started up again in 1951 with the Wagner family in charge but without Winifred at the helm.

The Festivals are still going strong and the waiting list for tickets - unless you happen to be a celebrity or a politician - can be years. All-in-all the audiences still seem to prefer traditional staging and have responded negatively when directors have tried to modernize the performances. Also descriptions of the audience sitting for hours in a sweltering and packed auditorium with the men doffing their tuxedo jackets as their cell phones clatter to the floor make you wonder - if it wasn't for the honor of the thing - that a better way to enjoy Richard's music is to simply turn on your iPod or sit at your computer.

Recently a music critic bewailed the "music illiterates" who won't listen to Wagner. Well, music illiterates may not listen to Wagner but there are professional musicians who won't listen to him, either. One musician who does not is Anita Lasker-Wallfisch, who in the 1930's was a young cellist living in Poland. Since she was Jewish, she was arrested and sent to Auschwitz concentration camp. She survived because she was assigned to be a cello player in the women's camp orchestra. After she was freed in 1945, she launched her long and distinguished musical career. But she has never listened to Wagner again.

There's lot's of other reasons people don't listen to Richard. Some of it is simply the well-known "Let's-trash-the-great-man-so-we-can-think-we're-greater" phenomenon. After all, if Richard and his acolytes think his music is great and you know he was a musical hack who wrote in motifs because he couldn't craft a real sustained melody, then that means you're a better judge of music - and hence smarter - than the aforesaid acolytes and even Richard himself. Or it may be you just don't like his music, just like a lot of Wagner fans don't like the music of Muddy Waters, Son House, or the Reverend Gary Davis. (Of course we can all agree that people who don't like Muddy Waters, Son House, or the Reverend Gary Davis really are music illiterates.)

But if you do like Richard's music, by all means listen to it. There's no questioning he really was a musical innovator. The modern staging of operas - with the lights out during the performances and the orchestra out of sight - all began with Richard. He also introduced new atonal chords, didn't bother resolving discordant harmonies, and linked an opera's characters with particular melodic themes. In these (and other) ways Richard's music anticipated today's film and television scores and advanced orchestral compositions to the modern schools.

Hm. Maybe advanced isn't the right word.

In any case you can listen to Richard's music anywhere. True, attempts to schedule live concerts of his music in Israel have not come off, but his music has been played on prime time Israeli radio. There's even an Israeli Wagner Society, and in 2011, the Israeli Chamber Orchestra performed Richard's music at Bayreuth to enthusiastic applause.

So what can we say about a composer whose music is among the most popular in history and yet will always be linked with the name of a mass murderer who hadn't even been born when the last Wagnerian note was written?

Well, Richard, that's what you get for being such a jerk.

References

Books and Articles

Richard Wagner: A Life in Music, Martin Geck, University Of Chicago Press, 2013

Richard Wagner: The Last of the Titans, Joachim Köhler, Yale University Press (2004)

Wagner: A Biography, Curt von Westernhagen, Cambridge University Press, 1981

Richard Wagner: The Man, His Mind, and His Music, Robert Gutman, Harcourt-Brace, 1968. An early single volume biography. A good deal of information of Richard's life, but as always, when interpreting the "meaning" of the operas as a way to determine what Richard actually thought, you have to be wary. Also here is where we read that a letter from Hans von Bülow referred to the people of Munich as schweinehunde. This attestation will belie claims by some Americans that the word was actually made-up by English speakers.

Richard Wagner And the Jews, Milton Brener, McFarland, 2005. A more recent book that specifically addresses Richard's attitude and dealings with the Jews collectively as a people and the individuals of his personal acquaintance.

Wagner: Race and Revolution, Paul Rose, Yale University Press, 1996.

Wagner Beyond Good and Evil, John Deathridge, University of California Press, 2008

Richard Wagner: New Light on a Musical Life, John Digaetani, McFarland, 2013

The Cambridge Wagner Encyclopedia, Nicholas Vazsonyi, Cambridge University Press, 2014. Handy reference; ridiculous price.

Winifred Wagner: A Life at the Heart of Hitler's Bayreuth, Brigitte Hamann, Harcourt, 2007 (Original Title: Winifred Wagner oder Hiters Bayeruth)

Antisemitism. A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution, Richard S. Levy, ABC Clio, 2005.

"Winifred Wagner Sentenced to 450 Days for Aid to Nazis", Milwaukee Journal, July 2, 1946 (Available at https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1499&dat=19470702&id=Wh0aAAAAIBAJ&sjid=IiUEAAAAIBAJ&pg=2571,448520&hl=en)

The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century, Houston Stewart, Chamberlain, The Bodley Head, 1911. For heaven's sake, don't wast you money if you want to read this. The text is available for free (see https://archive.org/details/TheFoundationsOfThe19thCentury_362).

"Politics and the English Language", George Orwell, Horizon, April, 1946, pp. 252 - 265; Reprinted in In Front of Your Nose, 1945 - 1950, Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters, Vol. 4, pp. 127 - 140.

Visual Media

1874 - Wagner and the Ring Cycle, Howard Goodall's Great Dates, Presenter: Howard Goodall, BBC

The Music of Richard Wagner, Instructor: Robert Greenberg, The Teaching Company. Not only about Richard's music but also has biographical information. One lecture includes the entire opening "Dark and Stormy Night" paragraph of Paul Cliford.

Hitler und der Wagner-Clan: Götterdämmerung in Bayreuth, Spiegel TV, 2002.

Wagner and Me, Presenter: Stephen Fry, BBC, 2010.

Internet Sites

Wagner Operas, http://www.wagneroperas.com

"Richard Wagner's Legacy in Dresden", http://www.dw.de/richard-wagners-legacy-in-dresden/a-16909028

Bayreuther Festspiele, http://www.bayreuther-festspiele.de/

"The Controversy Over Richard Wagner", Jewish Virtual Library, http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/anti-semitism/Wagner.html

Richard Wagner: The Devil Who Had Good Tunes, The New Jersey Jewish Standard, August 7, 2009, http://jstandard.com/content/item/richard_wagner

Wagner and Hitler, Larry Solomon, http://solomonsmusic.net/WagHit.htm

The Wagner Library, http://users.belgacom.net/wagnerlibrary/

Siegfried Wagner: The Last Romantic, http://www.siegfriedwagner.com/en/siegfried-wagner.html. A website for the documentary of the same name.

"Wagner's Dark Shadow: Can We Separate the Man from His Works?", Dirk Kurbjuweit, Spiegel Online International, http://www.spiegel.de/international/zeitgeist/richard-wagner-a-composer-forever-associated-with-hitler-a-892600-2.html

"Chopin The Anti-Semite", Damian Thompson, Daily Telegraph, http://blogs.telegraph.co.uk/culture/damianthompson/100006942/chopin-the-anti-semite-not-a-fanatic-but-he-didnt-like-jews/

Karl Marx to Friedrich Engels, March 22 - 23, 1853, Collected Works, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Vol. 39, Peter and Betty Ross (translators), International Publishers, 1983. For those who are interested what Karl wrote was "That angel [the Princess Eugéne] suffers from an indelicate complaint. She is passionately addicted to farting and is incapable, even in company, of suppressing it. At one time she resorted to horseback riding as a remedy. But this having now been forbidden to her by [King Louis Napoleon] Bonaparte she 'vents' herself." At this point Karl switched from German to French and added, "It is only a noise, a faint murmur, a nothing, but then you know the French are sensitive to the slightest puff of wind."

Notes on Absolute Pitch, Edward Gold, http://www.egoldmidincd.com/absolute_pitch.html A first hand account that tells us Lenny always denied he had perfect pitch. For what it's worth, Lenny also said he once stood in front of a mirror to practice conducting and it made him laugh so much he never tried it again.

Wagner Tuba, http://www.wagner-tuba.com/. Has a nice concise biography of Richard.

They Never Said It: A Book of Fake Quotes, Misquotes, and Misleading Attributions, Paul F. Boller Jr., John George, Oxford University Press, 1990.

Websites X, Y, and Z. To avoid apparent criticism of individuals, oblique references are sometimes best.

Return to Richard and Cosima Wagner Caricatures