Vance Randolph

Cantankerous Scholar of the Ozarks

A Most Merry and Illustrated Tribute

Vance Randolph was the pioneering folklorist of the Ozarks. By the time he died, Vance had written a series of books that were and remain the standard references for a culture that was largely unchanged from the mid-nineteenth century until the end of the Second World War. What scholar could possibly hope to match Vance's contributions to society and world knowledge with the publication of Down in the Holler, Who Blowed Up the Church House?, We Always Lie to Strangers, and of course, the iconic and masterful, Pissing in the Snow and Other Ozark Folktales?

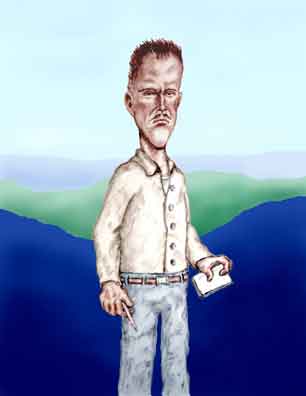

Vance Randolph

A Gentlemanly, Scholarly, and Onery Old Cuss

Vance himself was not from the hill culture. Instead he was born in Pittsburg, Kansas in 1892 to middle class and Middle Western parents. His father was an attorney (who died when Vance was young), and his mom was a schoolteacher. Always somewhat contrary, Vance dropped out of high school (much to his mother's dismay), but after a few years of dead end jobs he enrolled in the Kansas State Teachers College (now Pittsburg State University). He graduated in 1914, spent a year teaching school, and then enrolled at Clark University in Massachussetts.

Today it seems strange that a high school dropout could simply enroll in college and move on to attend what was one of the most innovative graduate schools in the country. But this was the era of transition when colleges were moving away from being affectations for rich kids who spent their secondary school years studying Latin and Greek to where they became (or at least hoped to become) institutions that taught marketable skills and strove to generate new knowledge. Also with the advent of land grant colleges and an increasing competition for students, entrance requirements had become more flexible. Schools were accepting even marginal students on the priviso that deficiencies would be made up after enrollment. In short, as long as you could convince a college to let you in, you could get in.

At Clark, Vance earned his MA in Psychology - the president, G. Stanley Hall, was a friend of Freud - and then contacted famed and pioneering anthropologist, Frank Boas of New York's Columbia University about working for a Ph. D. Vance wanted to study the people of the Ozarks. He had developed a fascination with the region and the people after his first trip to the mountains in 1899. But Frank dismissed such a plan as not studying real anthropology. For that, Frank thought, you had to go to Samoa (like his future student Margaret Mead) or at least up to Alaska or Canada to study the Eskimos.

Now the mainstream route for Vance would be to go ahead and research something Frank liked, get his degree and a university position, and then adopt folklore of the Ozarks as his speciality. But Vance, being Vance, made a very Vance Randolph decision. He just said to hell with it. "I sure as hell wasn't going to study Eskimos," he added. He went back to Kansas and supplemented his teachers' experience with that of an insurance salesman and a reporter. Then in November, 1917, the Army drafted him into World War I.

Vance served his country by spending a few months in the hospital. He came down repeatedly with a number of ailments, including mumps - "port and starboard, above and below", as he put it. By January 1918, the army saw no reason to keep on providing room, board, and pay to a soldier who would never see a foxhole. So Vance got his medical discharge and with it a small disability pension. Through the rest of his life Vance took great delight in milking the government for his veteran's benefits and laughingly telling others about it. As far as Vance was concerned the government had no business trying to make soldiers out of men who were completely unsuited to the military. If they paid him for being sick, well, that was just tough tiddy. "Serves the sons-of-bitches right," he said.

Out of the army, Vance spent the next year or so traveling around the country from California to Florida. It was bumming around, yes, but he was also getting his first real experience at observing the lives and ways of the people of the country. He then returned to Kansas to spend some time back home with his mom. As skewed toward the end of the bell curve as Vance could be, he always got along well with his very mainstream mother, and his very mainstream mother was always willing to support Vance, financially and otherwise. But in 1920 and approaching thirty, Vance decided to do what he had wanted to do at Columbia. He was going to study the people, life, and culture of the Ozarks. Following some additional time spent at the University of Kansas, he bought a farm for $300 at Pineville, Missouri and lived in the Ozarks for the rest of his life.

Of course, even distinguished folklorists have to eat, and except for his one true best seller (three guesses which it is from the titles listed above and the first two don't count), Vance's studies never made him much money. Then as now, articles in academic publications don't pay anything, and even after he established himself as an authority on Ozark culture, his publishers seemed rather mean - certainly when you compare them to today's book moguls who might dish out a five million dollar advance to some disgraced elected official who is also probably receiving a fat government pension and complete healthcare at taxpayers expense (rant, rave, snort). Vance certainly had to get by on less. In one contract the publisher - a major university press - paid no advance at all and no royalties for the first 1000 copies. An earlier publisher even made Vance himself buy up a number of the books himself. Somehow, then, Vance had to make a living.

Vance was a facile and fast writer, and in the pre-electronic (and pre-Internet) days magazines were a popular form of entertainment. This was the day when some magazines came out once a week and subscriptions were the main source of revenue. The result was a clean legible format where the pages were not peppered with ads to the point of illegiblity (hard to believe by today's standards). So the market of burgeoning men's and outdoor magazines, most of whom paid decent fees to freelance writers, provided some relief to Vance's pocketbook. Still magazine writing wasn't enough to keep him and his wife, Marie Wilbur (whom he married in 1930), afloat. The marriage was not a happy one, and although Marie was from a well-to-do family, when she died in 1937, she left Vance a whopping $1. Ultimately, Vance turned to what even he called "hack" writing, and fortunately he had the perfect contact to make it pay.

In his reporting days, Vance had been employed for the socialist paper Appeal to Reason in Girard, Kansas where one of his colleagues was a slightly older man, Emanuel Julius. But Julius had higher (or at least more ambitious) aspirations than reporting for a weekly newspaper. So he soon left the Appeal and set up his own publishing company (also in Girard). He adopted the somewhat more elegant sounding name of E. Julius-Haldeman (his wife was a Haldeman) and began a paperback business.

Operating under a surprisingly idealistic business plan, Julius decided to make the classics available to the average man at cut rate prices and in volumes that you could easily carry in your pocket. His "Little Blue Books" - and the later the "Big Blue Books" - sold in the millions, usually for a dime but some as low as two cents. Julius soon expanded his line to include original works some by the world's most distinguished pubic figures and authors - Bertrand Russell, W. E. B Dubois, Will Durant, to name three. Unlike some other publishers, he treated his authors well. Vance could make $600 or more ghost writing a single book - very good money for the time, but more importantly, Julius also paid promptly. Vance would send in a manuscript on Monday and receive the check by Thursday. The work, though, was what is now called "for hire" which means Vance got a flat fee but no royalties.

Bertrand Russell

Vance's Fellow Author

Julius provided Vance with a steady income even during the depression, and Vance was never the writer starving in a garrett (or in his case, a mountain cabin). Despite his sometime claim of "being broke", people remembered him as distinctly middle class, eating steak for breakfast and well-dressed at all times. Oh, his economic ups and downs were real enough, but Vance also had considerable skill in using his misfortunes to good advantage.

Some of Vance's books for Julius were collections of Ozark folktales or other historical Americana, and for those he would often write under his own name. But other volumes carried various noms de plumes. Julius also found that a title could be more important than content (people, it seems, do judge a book by its cover). So when the Blue Book edition of Guy de Maupassant's The Tallow Ball sold only a few thousand copies, Julius then changed the title to A French Prostitute's Sacrifice. Sales skyrocketed to 50,000 a year, and Julius realized there was still another line of books for his press. Soon Vance was sending in (pseudonymously) such titles as the Confessions of a Goldigger: How to Get a Husband, the Autobiography of a Pimp, the Autobiography of a Madame, and the final chapter for The Modern Sex Book titled "Sex and the Whip". It was, as they say, a living.

That said, it was Vance documenting the Ozarks and its people, their stories, customs, and beliefs that made him one of the most famous folklorists of all time. Vance's work was particularly valuble because he was not the city bred academic who visited a region, asked questions of the inhabitants (who sometimes took delight in "greening" their occasionally credulous interrogators), and went back to the ivory towers to write their findings up. Instead Vance lived in the Ozarks, fishing, drinking, fighting, gambling, dancing, cussing, and all the while writing down what he saw, heard, or was told.

Because he lived in the region for so long (longer than some of his informants), much of his information came from his friends who would speak to him about topics they would never have broached with a casual tourist or a professor on a "collecting" trip. Almost as soon as he moved to Pineville, Vance began writing articles for folklore journals and magazines. In just a few years, he was being cited as the premiere expert on the Ozarks.

Although Vance became a true Ozarker - he lived in the mountains for sixty years - he always saw himself as something of an outsider, an observer. He was also often regarded as such by many of his neighbors who sometimes were slightly censorious of his "furriner's" attitude toward their beliefs. "You ain't serious minded, Vance," one elderly woman said after he had made a light hearted comment about a particular folk practice, "an' it ain't no use to tell you 'bout such things."

From the first Vance was in a quandary about how to best depict the speech of his neighbors. Writing the oldest Ozark dialect accurately - skeered for "scared, sass for "sauce" - came off as condescending, sarcastic, and ironically, as inaccurate. He also found the menfolk, like those most anywhere, peppered their language freely with four letter words. Not only did this render much of the material unprintable (this was long before the liberalization of literature), but it was simply monotonous and looked wrong when read. So usually Vance kept to standard spelling and retained just enough verbal fireworks to represent the flavor of the tale but otherwise preferred not to bowdlerize outright. Still, if the latter practice would keep something out of print and Vance thought the story too good to omit, he would reluctantly resort to his blue pencil.

Vance remained grateful to Julius for keeping the wolf from a folklorist's door, but his serious books were printed by more mainstream publishers. In 1931, Vanguard published The Ozarks: An American Survival of Primitive Society. This book cemented Vance's already established reputation as the foremost scholar on the Ozarks. By 1933 he was well enough known that he was offered a job in Hollywood writing movie scripts about the "hillbillies". Vance couldn't turn down the $200 a week in depression era American dollars, and he and his wife moved to Tinseltown. He worked with a number of other writers, and Vance apparently was the originator of the script motif where two people who are speaking in dialect need a translator into standard English (a scenario later used in movies like Airplane and Austin Powers in Goldmember). But none of Vance's scripts were produced, and when one fat cat Hollywood producer complained the dialog wasn't authentic, Vance packed his bags and headed back to the Ozarks.

Vance's books were well received by the popular critics (even in high falootin' places like the New York Times Book Review), but at first the academic reviewers pretty much ignored him. Despite his own bonafide educational credentials he was never associated with any university, and with some important exceptions, the "perfessers" looked on Vance as a mere (ptui) "collector" (although they acknowledged he was a good one). Then in 1946 Vance submitted the manuscript of Ozark Superstitions to Columbia University Press, and it issued the next year under Columbia's imprimatur. Still available from Dover and retitled as Ozark Magic and Folklore, it was his first book issued by an academic publisher and is one of Vance's best.

Ozark Superstitions put Vance on a firm academic standing, but got him - as did some of his other writings - in a bit of hot water with some of his neighbors. This was, after all, the time of the jokes of the "hillbilly", a stereotype that in modifications remains a socially acceptable venue for comedy even today ("There were two rednecks driving down the road when ..."). Rather than feel honored that their customs and speech were the subject of a prestigious university press, the local residents thought Vance was holding them up to ridicule. Writing up amusing tall tales is one thing, but spending two chapters telling how many of his neighbors believed in ghosts and witchcraft so raised the ire of some inhabitants (although the chapters were quite accurate) that Vance found himself denounced and villified, at times to his face. However, in the book Vance had pointed out that people in big cities of the East (where seances and astrology were a favorite pastime) were superstitious, too. Certainly today with the world going through an unprecedented rise in incredibly absurd and superstitious beliefs (although rarely termed as such), the Ozark hillman from Vance's time who would "conjure" away a bad crop by planting his corn in a particular pattern looks like the epitome of rational thought.

Vance's studies were not limited to folktales and practices. He had been collecting folksongs since his arrival in the hills, and in 1941 Alan Lomax of the Library of Congress asked Vance to record Ozark folk music for the LOC Archive of Folksongs. Vance agreed with the stipulation he had to have some financial support (a very reasonable request). Alan wrangled Vance a grant of $1500, loaned him a recording machine (a bulky contraption that recorded directly onto aluminum disks), and eventually Vance supplied Alan with more 800 songs. Many of these were featured in Vance's four volume Ozark Folksongs, and a selection of original field recordings have been released on CD. You can even hear Vance himself on "Tie Tacking's Too Tiresome". After listening to the 29 second song you want to shout, 'Vance, for God's sake, go home and write a book!

Alan Lomax

Wrangling Support for Vance

When Ozark Superstitions was published Vance was fifty-five and after another decade he had five more titles from Columbia under his belt. His work had made him famous - even iconic - in folklore circles but only one book provided him with a substantial income. That was (did you guess it?) Pissing in the Snow and Other Ozark Folktales. Long circulated among scholars in mimeograph and kept on file at the Library of Congress, it was finally published in 1976 by the University of Illinois Press with Rayna Greene (now of the Smithsonian Institution) acting as his agent. Of course Pissing was a best seller, particularly after it issued in a paperback edition, but by then Vance was arthritic and bedridden and living with his second wife, Mary Celestia Parler, in a Fayetteville nursing home.

Like his financial prosperity, official honors also came surprisingly late, and it wasn't until 1978 (when he was 86) that Vance was elected as a Fellow of the Amercan Folklore Society. The honor was long overdue, but he was appreciative and wrote his friend Herbert Halbert (who was instrumental in getting Vance elected), "If a ribbon goes with [the award], I'll pin it on my pajamas." Vance died in Fayetteville two years later, age 88.

People who knew Vance recalled a gentleman and a scholar who could nevertheless still be a bit peppery and cantankerous. As he did with his laments of poverty, he often used his various physical complaints to good effect and was a man who truly enjoyed ill-health much of his life. Vance often bowed out of social functions due his various maladies - including but not limited to (so Vance said) bouts of colitis, strokes, and the surprisingly convenient but apparently mild heart attack. True Vance had real ailments, but like as not if concerned visitors would show up afraid the aging folkorist might be on his last legs, they would be surprised to find an elderly, but to all appearances healthy and vigorous gentleman who received them with courtesy.

The more onery sides to Vance's nature, we suspect, were often just the surfacing of his sense of humor, somewhat barbed by nature and refined by his living most of his life among the deadpan hillfolk. So when his relationship with Mary Celestia had become a bit more than a professional collaboration, he could write, "Dear Mary Celestia, A woman's place is in the f------ home. Ever yours, Vance." Mary Celestia, a professor of English at the University of Arkansas and a major folk scholar in her own right, knew Vance was joking.

The Ozarks that Vance wrote about were on their way out even while he lived. If you drive through the region now and move off the interstate, you'll find the residents, instead of sitting on their front porches talking about weather signs or goober doctors, will be inside watching reality TV or ESPN, surfing the net, or text messaging their friends. If you do see someone sitting on his porch plucking a banjo, like as not the "native" was born in a big city up north, works for a technology company, and got hooked on bluegrass music while in college. As elsewhere civlization has produced its dubious blessings, and some towns and cities in the heart of the Ozarks have violent crime rates every bit comparable to "big cities" of the east. Fortunately much of the bounty of Vance and his colleagues collected of the older era is safely stored in various University and government archives which as time goes on will (hopefully) become electronically accessible to those who themselves enjoy digging in to what Vance wrought.

By the end of the 1950's, Vance had pretty much completed what he set out to do. When he turned 65, he wrote Herbert Halbert that he now had enough to get by, and he didn't think he would write any more books. There was no money in it, he said, and added (not really accurately) that his books were of no interest to anyone except a small group of folklorist. "Which is OK by me," Vance wrote, "and they can all kiss my ass, as I told the children this mornin'."

References

Vance Randolph: An Ozark Life, Robert Cochran, (University of Illinois Press, (1985). The - quote - "scholars" - unquote - from the East Coast Ivy League or their West Coast libertine counterparts who scoff that anything of merit or culture could come from the Ozarks should be forced fed this book. I mean, is there anything from UPenn or Berkeley that can even begin to compare to the scholarship, literary merit, or moral teachings of Down in the Holler, Who Blowed Up the Church House?, and Pissing in the Snow and Other Ozark Folktales? As Eliza Doolittle said, "Not bloody likely."

"Vance Randolph (1892 - 1980)", Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture http://www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net/encyclopedia/entry-detail.aspx?entryID=2265 A nice online article by Professor Cochran.

Most of Vance's books are out of print now, but one thing the Internet did - amazingly - was to give a shot in the arm to the used book market. Now virtually (no joke intended) any of Vance's volumes are just a mouse click away. Some of Vance's books which CooperToons feels qualifed to review (which means he's read them) are:

Ozark Folksongs, Orignally published by the Missouri State Historical Society, a more accessible and abridged version issued in the 1980's by the University of Illinois Press. Most songs have the notation for the melody and the lyrics. Naturally most of the songs are found among inhabitants of the Appalachians and eastern mountain regions which is of course where the Ozarkers came from.

Ozark Folksongs, Comparct Disk, (Rounder). These are a selection of the songs collected by Vance and sad to say the quality is pretty poor even for field recordings of the era - or at least field recordings that have been released commercially. Also there is relatively little pure instrumental music and a considerable amount of a cappella singing. But the folk enthusiast will find this collection of note and some of the songs well worth listening to. Particularly of interest is "Chicken Reel" played by guitarist Jimmy Denoon. Although the song was recorded sometime between 1941 and 1942, Jimmy's playing presages that rapid single note flat picking often thought of being originated by Doc Watson. Of course, Jimmy wasn't as really good as Doc, but he was still pretty durn good.

Another surprise will no doubt be that although the performers definitely have a twang to their speech to varying degrees, it certainly isn't the extreme caricature babble of the movie hillbilly. In many cases it's actually more pleasant that the abrupt "Hey! Yo!" you oft times hear in the Town That Snowballed Santa Claus. Today, of course, dialectal differences are going the way of the Dodo's cluck. A teenager in Little Rock is likely to sound no different than one in Chicago and both probably picked up their favorite bon mots from the TV sitcoms.

Ozark Superstitions, Columbia University Press (1947), reissued as Ozark Magic and Folklore, Dover (1964 to date). One of Vance's best books, it's particularly instructive to note the similarities between the - quote - "backwoods superstitions" - unquote - and the beliefs that so permeate the modern Hollywood jetset and others of that ilk no matter how much the latter try to put their superstitions into a pseudo-scientific patois. If anything the Ozark hillfolks were more discerning before accepting the outlandish.

Vance was always quick to point out which "superstitions" were actually just customs and regarded more or less as jokes - such as the saying that the man who takes the last biscuit at dinner will soon kiss the cook. Others have a more rational - or at least practical - basis such as eating black-eyed peas at New Year's Day for good luck, particularly in the dish called "Hoppin' John". Hoppin' John with a slice of warm buttered cornbread? Beats the pants off anything from elitist haut cuisine establishments around UPenn or Berkeley any day.

Who Blowed Up the Church House? And Other Ozark Folk Tales , Columbia University Press (1952). More or less traditional tales many with a humorous and at times racy bent, rendered in the hillman's style of understatement. As with most folktalkes, the stories are told as if true but many are clearly derived from stories from the British Isles (one has the same plot as the popular Irish tune, "The Old Woman of Wexford"). The reader himself will be able to confirm the tales have long been in oral circulation. CooperToons heard "Oolah! Oolah!" when he was but a lad, but titled as "Ah-Gussy-Hi!"

On the other hand, who knows? Maybe some stories were true. Others were clearly just jokes and told as such (Doc Watson sometimes told a version of "The Stranger and the Beans" at his concerts), and a few are expurgated, bowdlerized, and sanitized versions from Pissing in the Snow. But even a number of the remaining stories are on the risqué side telling of feisty and freespirited young gals, both married and not. "She Always Answered No" ends with the young feller throwing the gal into the hay, and they "was as good as married right then and there".

A bit of a surprise is the tolerance the hill people had for outsiders and those of other cultures - a greater tolerance arguably than you find today among the so-called educated urban classes today. When a group of Native Americans decided to hold a rain dance in competition to a preacher's prayer meeting for the end of a drought, the preacher naturally dismisses the rain dance as a bunch of foolishness. But, he thought, this was America and people are entitled to believe and practice what they want. Naturally, the rain dance worked and the preacher's prayers didn't, again introducing (at least today) another surprise for the readers. Although it was the practice of "proper" Ozarkers to attend the weekly services, in Vance's day and before, a number of solid Ozark inhabitants were surprsingly skeptical and even disdainful of organized religion in general and preachers in particular.

Down in the Holler: A Gallery of Ozark Folk Speech , University of Oklahoma Press (1953). CooperToons read this as an assignment in a college course - not at an Ivy League or West Coast elitist school like UPenn or Berkeley you can be sure. The book doesn't denigrate or ridicule Ozark speech, it just reports it. Vance also distinguishes between true Ozark dialect and made-up "hillybilly" talk (an Ozark hillman always said creek, never crick). One chapter, "Taboos and Euphemisms", foreshadow Pissing in the Snow and actually stirred up a bit of controversy when the book came out.

Pissing in the Snow and Other Ozark Folktales, University of Illinois Press (1976). If anyone doubts that nihil novum sub sole you can look at the daguerreotypes in Uwe Scheid's 1000 Nudes (Taschen, 1994) - at least that's what CooperToons has heard - or read Vance Randolph's Pissing in the Snow and Other Ozark Folktales - which CooperToons has. This was Vance's magnus opus which was published at the end of his long and distinguished career, and many of these tales will be recognizable to the average reader. True, the hoi polloi may read the stories as mere "dirty jokes", but some of the informants told Vance they heard these "tales" as early as the mid-1800's. So clearly they are part of American folk tradition. Besides, how can anyone not accept as the highest culture such tales as "Pissing in the Snow", "First Time for Trudie," "Why God Made Stickers", "Cats Don't Take No Chances", and "The Double Action Sailor".

Some dialectal differences may be confusing to city slickers. In Pissing in the Snow, the word which commonly denotes a grown male chicken is, as elsewhere, also used in making a rather coarse masculine human anatomical reference. In the Ozarks and certain regions of the South, though, the word is not (or was not at one time) a reference to the masculine utensil which the Romans called one of the "parts that are held in reverence". It was used for the feminine counterpart.

As in Who Blowed Up the Church House?, many tales in Pissing in the Snow are universal throughout the world. While he was living in the Ozarks, the author of CooperToons heard the tale called "Wahoo!" from Pissing in the Snow, but it was called "Suki-Nuki!" The protagonist also played golf, not pool. At the telling, though, a professor who originally hailed from Egypt said he heard the same story when he was a young boy living in Alexandria.

As always part of the effect is when the teller of the tales, jokes, or what-have-you uses the vernacular, but a brief review of "Wind on His Guts" must suffice. A farmer was having digestive problems and after a particular fetid blast which drove his family from their house, his wife told him to go to the doctor. Otherwise she and the kids would have to go stay with her folks. The man grumbled but went to the doctor. After the farmer demonstrated the problem in the office (which drove away all the other patients), the doctor told him to eat plenty of garlic, raw onions, and wild ramps (leeks) for dinner and before he went to bed to always eat a half pound of Limburger cheese. "Do you reckon all that will cure me?" the farmer asked. "No, I don't think it will cure you," the doctor admitted. "But it might help some.