Winston Churchill

The Greatest

Briton

American

Other

of All Time

(Select One)

Winston's Roots

Although present on the occasion, I have no clear recollection of the events leading up to it.

- Attributed to Winston Churchill About His Premature Birth

Of course all the attributions in the world will not change a bogus quote to a real one. And indeed like Yogi Berra, Winston didn't say all the things he said.

He certainly didn't make the above quote despite it's attestation on a popular informational website and its inclusion in a major scholarly biography. There is no record that Winston made any such statement.

But at least this quote gives us a handle on Winston's Brooklyn roots.

Ha? (To quote Shakespeare). Brooklyn?

Yes, Brooklyn.

Brooklyn, USA???????.

Yes, Brooklyn, USA.

The truth is Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill was ...

50%

50%

That's because Winston's mom was Jennie Jerome, a lady who was born and raised in yes, Brooklyn, USA.

And just how the heck did a gal from Brooklyn end up begetting the greatest Briton (or is it  ?) of all time?

?) of all time?

Well, that's easy to answer.

Jenny's family was rich.

Of course, back then - the mid-to-late 1800's - being rich was pretty average in Brooklyn. This was the time of the Guilded Age, and Brooklyn was the place of high society (it's a nice town now, of course, and has a great museum).

But having lots of rich people in your neighborhood created a problem. Just how could you lord your wealth over your snooty neighbors?

Well, one sure fired way to out-snob everyone was to get your daughter married off to a young swain of the British nobility. That's what Jennie's folks did, and in 1874 they got their daughter married off to Lord Randolph Henry Spencer Churchill.

Now you should not think of this union just as something machinated by powerful families. The idea was Jennie's and Randolph's. Jennie's mom had taken her to Europe (after some rather unpleasant stories surfaced about Jennie's dad) where at one fancy soiree she met Randolph. Each began eyeballing the other, and within a year they got hitched.

For her part, Jennie shouldn't be thought of just as a gold-digging society debutante. For one thing Randolph wasn't that rich, and Jennie was an intelligent and accomplished woman. She became a writer and editor and was involved in charitable and philanthropic work.

Randolph's personal life, on the other hand, reads a bit feckless. He also comes off a bit scatterbrained, and to American eyes, he looks a bit of a dweeb. And once he got married to Jennie, the family was dysfunctional from the get-go.

You see, there was much discussion about both Randolph's and Jennie's - ah - "extracurricular activities". Although it was taken for granted that a good Victorian husband might take a side order every now and then, Jennie's outside activities have also been the subject of considerable speculation. After all she was married (gasp!) three times, and the last was to a man three years younger than Winston. According to some, she had as many as 60 special male friends over her lifetime. And when we say they were friends, we mean they were friends.

Of course, other scholars say this is utter nonsense. Such claims, they say, are more a comment on our own tabloid society rather than being objective judgements about Jennie and her world. Besides in the Victorian era - despite rudimentary methods of population control - if Jennie had 60 boyfriends she'd certainly have had a larger brood than Winston and his younger brother, John. And despite scurrilous claims that John didn't resemble their dad, the similarity about the eyes says otherwise.

That said, like many a rich 19th century British lordling, Randolph became a member of Parliament. In 1874 - the year he married Jennie - he was elected to the House of Commons for Woodstock, a small town about 8 miles northwest of Oxford. Again officially Randolph was successful and his position important. But without going into details, he seemed unable to do anything without ticking people off.

Well, perhaps a little detail is in order. Among the people Randolph ticked off was Edward, the Prince of Wales and the future King of England, Edward VII. In 1875, Bertie - as he was familiarly known (his real name was Albert) - had been visiting India where among other things he was spending his time riding elephants while shooting tigers. In his entourage was a long time friend, the 7th Earl of Aylesford.

The Earl's name was Heneage Finch. His father was Heneage Finch, the 6th Earl of Aylesford, who in turn was the son of Heneage Finch, the 5th Earl of Aylesford. The lineage went back centuries with Heneage Finch being the 4th Earl of Aylesford, Heneage Finch, the 3rd Earl of Alyesford, Heneage Finch, the 2nd Earl of Aylesford, and winding up with Heneage Finch, the 1st Earl of Aylesford. Henage in turn was born to the Earl of Nottingham, Heneage Finch. Heneage's father was Heneage Finch, who held the important judicial post of Recorder of London. Mercifully, Henge's father was named Moyle.

While he was in India, Heneage - actually that was his middle name and his friends called him Sporting Joe - received a letter from his wife, Edith, née Peers-Williams. She informed him that she was - as the Victorians said - "with child". But should the child be male there was no need to reduplicate the boring nomenclature of the family tradition. After all, the child's father was not Sporting Joe.

Instead it was a family friend the Marquess of Blandford, and Edith said she was planning to run off with him. And the Marquess of Blandford was none other than George John Godolphin Spencer Churchill, who was, of course, Randolph's brother.

Sporting Joe nearly dropped a load. He telegraphed his mom to go pick up the kids and keep them until he got back to England. His explanation was only that a "terrible misfortune" had occurred. Sporting Joe high-tailed it back home, foaming all the way about dealing with George, "the greatest blackguard alive".

Naturally Sporting Joe wasn't that happy with Edith, either, and he began taking steps to dissolve his marriage. Although marital split ups were more common in the Victorian days than often believed, it wasn't routine. But staying married to a spouse living with someone else was far worse.

Randolph, though, didn't want his brother to be involved in a public scandal. So to - quote - "fix things up" - unquote - Randolph first convinced his brother and Edith not to set up housekeeping. Of course he still had Sporting Joe to deal with, and here we get to see Randolph in action.

It seems that Edith had other admirers as well. In fact, Bertie had written her some letters which must have been pretty steamy. At least they were - as Randolph said in typical British understatement - of a "most compromising character". How Randolph learned of the letters is a mystery, but evidently someone was a blabbermouth.

Randolph went directly to Bertie's wife, Alexandra, the Princess of Wales. Demonstrating his typical Randolphian lack of tact, he told Alexandra that Bertie must use his influence to keep Sporting Joe and Edith together. If not, there would be other - ah - "unpleasantness".

Which was? Alexandra wondered.

Well, if the matter got to court, Randolph said, he'd make the letters public. They would then become part of any proceedings, and Bertie would have to testify. The scandal would then fall on Bertie's head, and he would never become king.

Bad move, Randolph. When Bertie heard of the ultimatum he wrote Randolph asking when and where he wanted to have the duel. Randolph wrote back and, which was an even greater insult to the future king, he refused to take the challenge seriously. Randolph's response implied that Bertie was a coward, since he was challenging a gentlemen knowing that the duel would never take place.

Benjamin Disraeli

He was involved.

How much Bertie's mom - none other than Queen Victoria - knew about the goings-on isn't clear. But we do know that someone called in the Prime Minister, Benjamin Disraeli. He went to Randolph and got the letters back (which were then burned). George was packed off to Dublin as the Irish Viceroy, and Randolph, after issuing a rather muted and insincere apology to Bertie, went along as his brother's private secretary.

For his part, Bertie said he would have nothing more to do with Randolph. He would not even appear at any function to which Randolph was invited. And Bertie also made it clear that anyone inviting the Churchills to the many teas, dinners, week-ends at country homes, or fancy balls that made up Victorian social life would also be on the Prince of Wales' [black]list. So Randolph and Jennie found themselves ostracized from high society.

And Sporting Joe? He didn't fair so well, and he vanished from England. When he finally reappeared, it was 1883 and in - get this - Big Spring, Texas. This is about 60 miles east-northeast of Odessa. Sporting Joe bought a ranch and entered into various local businesses while devoting his spare time to hunting, gambling, and drinking. All in all despite his English accent and fancy duds, he was popular and respected by the local ranchers and townspeople.

Sporting Joe's time in Big Spring, though, wasn't long. The story is that one day in January, 1885, he was playing cards with some friends in the Cosmopolitan Hotel. At one point he excused himself and went upstairs. He then got into bed and died.

Randolph's exile to Ireland was likewise brief, and he returned to Parliament. Somehow by 1886 he had risen to be the Chancellor of the Exchequer - the minister in charge of the country's finances - in the cabinet of the Prime Minister, Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, the 3rd Marquess of Salisbury.

By 1885, England was the largest empire in the world. But other countries - like Germany and the United States - were beginning to compete. Also England was finding it harder to produce all their needs domestically, and many agricultural products and industrial materials were being imported (much of England's raw cotton was from America).

So the cost of keeping England running kept increasing. And as always you have three not necessarily exclusive remedies: 1) bring in more money from taxes, 2) cut expenditures, and 3) go further into debt.

Randolph suggested austerity and proposed making cuts in defense - not a popular stand for a country that had armed forces practically covering the globe. The War Office - Britain's Department of Defense - objected, saying they needed even more money. Randolph in return said that they were providing bogusly inflated cost estimates.

Randolph's call for frugality had little support. So he decided he'd scare everybody by threatening to resign. That way Lord Salisbury and his boys would accept his policies, salaamingly beg him to stay, and he would magnanimously agree.

However, when Randolph sent in his letter, Salisbury told him not to let the door hit him in the ers (to quote Chaucer). Although Randolph remained an MP, he never held a ministerial post again.

How to explain Randolph's rather impulsive behavior? Well, a common story is that Randolph - again like many rich and relatively young men of his era - had contracted what the English called the French Disease, the French called the Neapolitan Disease, the Turks the Christian Disease, and their parishioners, the Vicar's Disease*. Most historians accept this diagnosis, but more charitable scholars have pointed out the symptoms could have been from a less censurable condition like a brain tumor. But whatever the cause of Randolph's infirmity, there was no cure. He died on January 24, 1895 at age 45.

When Randolph died, he left his family with considerable debt. This wasn't that unusual. A lot of people who had sported titles like Earl, Duke, and Count (sounds like a baseball team, doesn't it) maintained a lavish lifestyle and fancy country homes with little hard cash on hand. Fortunately, the Victorian era was the era of credit, but less fortunately, the debts kept getting passed down the generations.

Winston's World

When his dad died, Winston was 20 years old. He had been born nearly two months prematurely (wink, wink). As the son of a now debt-laden aristocratic family, it was decided that young Winston would join the military, which, if not a guarantee for great wealth, was at least an honorable calling. Of course, in Winston's time the honorable calling might involve firing howitzers at indigenous people armed only with spears. But then as now what is an honorable calling is defined by those doing the calling.

As a kid, Winston wasn't a great student - in fact, he was pretty darn rotten. He showed up late, was inattentive, and was quite a [goof] off. On the other hand, a teacher had told his dad that he didn't think that Winston really showed "willful" disobedience. The kid was smart, he said, and Winston's ability should put him at the top of his heap. But his actual work buried him at the bottom.

Naturally as many a young and lazy lagabout, Winston was convinced of his own greatness. He was going to do magnificent deeds, and as a soldier he could at least envision himself fighting for Queen and Empire.

So after a triple of tries, Winston managed to get into Sandhurst, the Royal Military Academy. Surprisingly he did well and graduated eighth out of a class of 150.

Now we have to digress. Officers in the British Army served their stints in chunks. They would have maybe seven months on their active military assignment which would be followed by three months back home for additional training. The other two months were rest and recreation where they could do as they pleased. Naturally most young officers wanted to live high on the hog for those two months.

As a young leftenant, Winston's pay was £150 ($730) a year. But he calculated that with his wish list - which included two polo ponies - he needed £500 per annum ($2400 at that time and about $70,000 today). The only source for the extra cash was his mom, and Jennie wasn't too thrilled to have to support her son's profligate lifestyle when she had her own profligate lifestyle to support as well.

But Winston was also Lord Randolph's son. And although Randolph was no longer around, he left Winston with plenty of connections. His mom was also willing to use her (considerable) influence with the family friends to help Winston out. So Winston got an idea how to serve Her Majesty and also pick up some extra cash.

First of all, Winston and Jennie got some of their influential family friends to get him transferred to places where there was plenty of action. Naturally, these were also the places that were in the news. Winston then contacted the editor of the Daily Telegraph, Thomas Heath Joyce, and got a contract to write articles about the goings-on. After first serving in Cuba (where he picked up a good selection of Havana cigars), Winston ended up going to Africa, India, and points East.

Winston's articles paid him pretty hefty fees, and he also wrote two books The Story of the Malakand Field Force about fighting in Pakistan and Afghanistan and The River War about the Sudan (where Winston took part in the last real cavalry charge in history). The money from the books and articles permitted Winston to afford the lifestyle he preferred, or at least it temporarily defrayed some of the costs.

Winston's Métiers

Possibly because being both a soldier and a well-paid correspondent caused resentment amongst his fellow officers, Winston left the army in 1899. It was at this time that Winston noted there was another Winston Churchill - in America. The American Winston Churchill - no relation - was a popular novelist and author who wrote books that virtually no one reads today.

Realizing there could be confusion, young Winston wrote to his American namesake:

London, June 7, 1899.

Mr. Winston Churchill presents his compliments to Mr. Winston Churchill, and begs to draw his attention to a matter which concerns them both. He has learnt from the Press notices that Mr. Winston Churchill proposes to bring out another novel, entitled Richard Carvel, which is certain to have a considerable sale both in England and America. Mr. Winston Churchill is also the author of a novel now being published in serial form in Macmillan's Magazine, and for which he anticipates some sale both in England and America. He also proposes to publish on the 1st of October another military chronicle on the Soudan War.

He has no doubt that Mr. Winston Churchill will recognise from this letter - if indeed by no other means - that there is grave danger of his works being mistaken for those of Mr. Winston Churchill. He feels sure that Mr. Winston Churchill desires this as little as he does himself.

In future to avoid mistakes as far as possible, Mr. Winston Churchill has decided to sign all published articles, stories, or other works, 'Winston Spencer Churchill,' and not 'Winston Churchill' as formerly. He trusts that this arrangement will commend itself to Mr. Winston Churchill, and he ventures to suggest, with a view to preventing further confusion which may arise out of this extraordinary coincidence, that both Mr. Winston Churchill and Mr. Winston Churchill should insert a short note in their respective publications explaining to the public which are the works of Mr. Winston Churchill and which are those of Mr. Winston Churchill.

The text of this note might form a subject for future discussion if Mr. Winston Churchill agrees with Mr. Winston Churchill's proposition. He takes this occasion of complimenting Mr. Winston Churchill upon the style and success of his works, which are always brought to his notice whether in magazine or book form, and he trusts that Mr. Winston Churchill has derived equal pleasure from any work of his that may have attracted his attention.

From his home across the sea, Winston Churchill replied:

Mr. Winston Churchill is extremely grateful to Mr. Winston Churchill for bringing forward a subject which has given Mr. Winston Churchill much anxiety.

Mr. Winston Churchill appreciates the courtesy of Mr. Winston Churchill in adopting the name of 'Winston Spencer Churchill' in his books, articles, etc.

Mr. Winston Churchill makes haste to add that, had he possessed any other names, he would certainly have adopted one of them.

But there was a new war to cover, the Boer War in South Africa. Actually this was the Second Boer War which was a continuation of the First Boer War.

The Boer Wars had nothing to do with battling windbags or contending with porcine combatants. Instead these were fights between the English of South Africa and the Dutch settlers in the regions called the Transvaal and the Orange Free Sate. The Dutch settlers said those regions were their own independent Republics, but the English claimed the lands were part of a "suzerainty" of British South Africa.

But in the meantime Winston left England and headed to South Africa to cover the story. He had joined up with some soldiers on a reconnaissance mission when their train was attacked by the Boers. Winston and the others were captured and sent to a POW camp in Pretoria.

Winston was not the type to let such minor reverses get him down. While the guards were being inattentive, Winston went over the fence. Eventually with the help of a mine manager (who was English) he got to Portuguese East Africa and then on to England. Soon he returned to Pretoria and was there when the other prisoners were freed.

Winston wrote up his adventures and became an instant hero. So what better to do now than run for Parliament? Well, that hadn't worked in 1899 (Winston lost as a candidate for the Manchester suburb of Oldham). But the next year he published a new book (his fourth). This was about his South African adventures, London to Ladysmith via Pretoria. Whether this book tipped the scales or not, Winston grabbed Oldham's seat in the 1900 election.

By 1902 Britain had won the war and took both the Transvaal and the Orange Free State as their own. During the course of the fighting, there were the inevitable stories that British burned towns and farms and left civilians to starve. The most notorious stories were about how the British rounded up 100,000 civilians and put them in concentration camps. Naturally casualty figures are difficult to estimate but most report state that at least 20% of the internees died and this included 50% of the children.

Because of such stories the British were considerably trashed in world opinion. During the war the now famous Arthur Conan Doyle had volunteered his services as a physician for a brief time. He also wrote a book (actually a pamphlet) that defended the motives of the British. Arthur did, though, urge reforms in the military, and it's commonly accepted that it was this book that got Arthur his knighthood. The Afrikaners didn't really buy Arthur's explanation, and bad feelings continued to exist in the Dutch South African communities well into the 20th century.

Winston Moves On

Winston, though, was making politics his career. Although often thought of as a Tory, Winston bounced back and forth between the Conservatives and Liberals with considerable élan.

Winston was certainly no doctrinaire politician. In his first election at Oldham he ran as a Conservative. But once at Westminster he voted Liberal on a number of issues. Unfortunately, then as now the leaders of political parties don't like their members voting except along the party lines. So in 1906, the Conservatives in Oldham "de-selected" Winston. That means they booted him out of the party and wouldn't let him run on their ticket.

Deselecting a candidate is a facet of British politics you don't have in the United States. In America when you register to vote, you pick your party, and that's that. Other party members have no say in who joins - which is why you have so many nutballs in otherwise mainstream parties.

This "pick-your-own-party" rule applies not only to voters but to the candidates themselves. In America, once you sign up, you're in. If the party bigwigs don't like your political views, and you end up getting elected, well, that's just tough tiddy.

But in England anyone can be kicked out of a party. And that's what happened to Winston. Of course, you can then join the other party if they'll have you.

They would indeed. The officials of the Liberal party, quite happy with Winston's support, invited him to sign up with them and run for Parliament. So in 1906, Winston ran for and was elected as, yes, a Liberal for North Manchester. As far as a candidate from one constituency suddenly representing another, more on that shortly.

The year 1906 was also when Winston published a biography of his dad. The biography actually brought Winston a good deal of cash - which was good since at that time MP's didn't get paid. On the other hand the US President Teddy Roosevelt, who had known Randolph personally, thought the book was a bunch of bunk. But Teddy's opinion didn't bother Winston who was now back working as an MP.

Things were even better than last time. As part of the new majority government, Winston was appointed the Under Secretary for the Colonies - a good start for a political career.

The Trials and Tribulations of Winston Churchill

Unfortunately, Winston soon had problems with his new constituents. You see, in the 19th century there had been an increasing angst about immigration. It was the same old horse-hockey you hear now. Immigrants were taking jobs, immigrants were changing the culture, immigrants were sponging off the government, immigrants were undermining the country's traditional values, immigrants were doing this, immigrants were doing that.

By 1905, when Winston was still representing Oldham as a Conservative, the government had pushed through the Aliens Act. The Aliens Act set limits on the number of people entering the country, and although not specifically targeting any specific group, many believed it was directed at Jewish immigrants.

Winston had always opposed immigration restrictions, and in particular said that specifically targeting Jews did nothing more than stoke the fires of prejudice. He was, of course, representing a constituency where 30% of the voters were Jewish.

Winston's objections were not simply political opportunism. His dad Randolph had a number of Jewish friends whom he regularly invited to his home (not something that was common). These guests were men of intelligence and attainment, and at school Winston also had a number of Jewish friends.

Still, the new Liberal Government of 1906 found that public sentiment strongly favored the act. For some reason Winston was assigned the job of implementing the policy. His Jewish constituents were quite irritated.

If that wasn't bad enough, then Winston got into hot water - and with his Roman Catholic constituents, for crying out loud! And that was because of the tetchy topic of Home Rule for Ireland.

Most Irishmen did not want to be Englishmen. Still many saw advantages of being strongly allied with England. One suggestion was for Ireland to have "Home Rule". That way Ireland would have its own Parliament, police force, and administration for domestic matters, and yet would remain within the British Empire.

But to the more patriotic Englishmen, Home Rule was the first step on the slippery slope to full Irish independence. So supporting Home Rule would look like you were soft on the "Fenians", that pesky group of Irishmen who were demanding - and sometimes committing acts of violence for - a completely independent Irish republic. And in his first days as a fledgling politician, Winston said he would never support Irish Home Rule.

But only a few years later Winston was such a strong advocate of Home Rule that he was mobbed by an angry crowd in Belfast who was demanding continued union. So just what made Winston do such an abrupt flip-flop on this contentious issue?

Remember. Winston was a politician. He was also representing a diverse constituency. There was not only the large Jewish plurality, but even larger numbers of Protestants and Catholics who were also split on political issues. Winston had to represent them all.

Then up came another quirk about English politics. At least at that time, whenever any MP was offered a cabinet level post, he would stand in a special between-term election called "by-elections". And in 1908 Winston was appointed President of the Board of Trade.

So now Winston had to run for MP yet again - and at a time when many of the voters saw him as a waffling and wishy-washy politician. Winston got the boot.

Now here's what's really strange about British politics. After the Manchester election there was yet another election scheduled for Dundee in two weeks. So Winston was able to run for Parliament again. And this time he won. Dundee, for those who don't know it, is in Scotland.

Ha? (Again quoting Shakespeare). You mean Winston was MP for North Manchester and then he simply up and ran for Parliament in Scotland.

Yea, marry (yep, Shakespeare). That's what he did.

Unlike in  where senators and congressmen have to be residents in the states they represent, in the UK you can run for MP of any constituency. Lose an election? Shoot, just go to the next constituency and try there. This seems strange to the inhabitants of Britain's former colonies, but that's the way it is.

where senators and congressmen have to be residents in the states they represent, in the UK you can run for MP of any constituency. Lose an election? Shoot, just go to the next constituency and try there. This seems strange to the inhabitants of Britain's former colonies, but that's the way it is.

There is, of course, an American variant of constituent hopping. Since residency requirements are typically only thirty days, a politician can move to another state and rent an apartment. After they live there a month, they can then register to vote and so run for office in that state. This does happen but it's not all that common.

Winnie and Clemmie

The year 1908 was also when Winston married Clementine Ogilvy Hozier. You can make a big deal out of that Clementine looked a lot like his mom, but it mostly seems the two just simply hit it off.

Even though Clementine came from an aristocratic family, it was even more dysfunctional than Winston's. Most historians even doubt that her nominal father, Sir Henry Montague Hozier, was her real dad. Clementine's mom, whose name was - no fooling - Blanche, had quite the reputation.

There can be no doubt that Clementine was important to Winston and his ultimate success. We've seen that the women in Winston's circle were not stereotypical Victorian ladies interested only in tea and tatting. Winston and Clementine discussed the issues that bedeviled the government, and she gave her opinion and evidently Winston listened. Certainly Clementine seems to have helped Winston settle down. At least he represented Dundee for the next 14 years.

Not that the marriage was without its stresses. Winston and Clementine had to spend considerable time apart, and when they were together they could argue most vehemently. For her part, Clementine was popular with the British and even more so, if this is possible, with the Americans.

Winston on Sidney Street

One thing the bigwigs in Parliament noticed was the way Winston really busted his rear end. So during all the time he was representing Dundee, Winston had nearly continuous cabinet positions. In 1910 he was appointed Home Secretary, which is a most important post and is responsible for domestic policy. It wasn't an easy job as Winston learned when he became involved in what has become known as the Siege of Sidney Street.

In England there was still a lot of worry about the immigrants, and one newly arrived group was from Latvia. The Latvians had left their country after Russian's October Revolution of 1905, and many settled in London.

Even at this early date people were talking about "Russian Revolutionaries" and supposedly there was a Latvian "gang of anarchists" in London causing all sorts of problems. The leader was someone named "Peter the Painter". Peter the Painter is particularly notable because, as was rumored for Emmett Grogan, many suspect he didn't exist.

On December 16, 1910, the police got a call from the locals living on Houndsditch Road. There were loud banging noises coming from the back alley of a jewelry store, and the residents feared something was up.

Indeed there was. The police found a group of men trying to break into the shop. The altercation was not trivial. Then as now, London bobbies were not armed, and in the resulting melee, three policemen were killed. The killers got away.

It was assumed that the criminals were a gang of the Latvian immigrants. There was a great hue and cry that something needed to be done about the foreigners. After a few weeks, the police got some tips that the gang was holed up in Sidney Street in Stepney, a district of London a wee bit north and east of the center of the city. So on December 16, 1910, a force of 300 policemen were dispatched and surrounded the house. They had no idea who was inside.

The use of firearms even by police was strictly controlled, and one man who could authorize firepower was the Home Secretary. So the officers got Winston on the phone (yes, they had telephones back then). Caught in his bath and dripping water, Winston stood in the buff and told the constables to use what force they needed.

Winston quickly dressed and hurried to Stepney (he was even caught on film). When he got there, a gun battle was underway.

Unfortunately when you're the man in charge and show up, then everyone expects you to be in charge. Winston realized that his military training notwithstanding, he now had to direct a force of civilian officers - which had its own complexities.

The officers directed a barrage toward the house, and soon the building was on fire. A fire brigade showed up and said they should be permitted to put out the blaze. But Winston said no.

Finally the fire burned itself out along with much of the house. When the police went in, instead finding the massive gang of anarchist immigrants, they found the bodies of two men.

There really wasn't much more anyone could do. Attempts to prosecute other "gang" members - who hadn't even been there - fell flat. Winston was criticized by his political opponents who said his presence was just a publicity stunt.

But criticism by the other MP's wasn't what kept a politician out of office. Apparently the voters didn't see any problems with the man in charge being at hand to be in charge. Winston was re-elected.

Then in the next year, 1911, came Winston's really big break. He was appointed First Lord of the Admiralty. This was the time when Britannia Still Ruled the Waves, and in some ways being the First Lord of the Admiralty was even more high-falootin' than being the Prime Minister. Winston had indeed hit the big time, and this is where he stayed for the next few years.

Winston at War

Of course by August 1914, the World (minus the United States) was at war. As the Lord of the Admiralty, Winston was one of the most important of the higher ups in what was soon being called the War to End All Wars.

Despite having many admirable qualities, Winston tended to look down his nose on non-European countries and questioned their ability to contend with Europe. So when Turkey, which as the Ottoman Empire controlled the Middle East, allied itself with Germany, Winston figured out a quick way to win the war.

Just attack Turkey, he said. Up against Tommy Atkins, the Turks will fold in a minute. Then Britain would then move up and squeeze Germany from both ends. Hey, presto!, the war would be over.

So in January 1915 and at Winston's insistence, the British attacked the Turks at the north end of the Aegean Sea that leads to the Sea of Marmara and onto the Bosporus Strait and the Black Sea. Called the Hellespont by the Ancient Greeks, in Winston's time the strait was named the Dardanelles.

But instead of folding and running, Johnny Turk, as the famous song says, was ready and had primed himself well. They stopped the British attack on the beachhead of Suvla Bay, and the English and their allied forces had to dig in.

The siege lasted a full nine months with both sides suffering horrendous casualties. Eventually the British forces up and pulled out.

Winston really had no choice. He resigned from the Cabinet. The 41-year-old former Lord of the Admiralty then joined the Royal Scots Fusiliers. He served in France until 1917 and then returned to politics.

Of course, when politicians [foul] up, their opponents try to take the advantage. Anticipating modern "What about [Fill-In-The-Blank]?" campaign tactics, people at Winston's rallies kept heckling his speeches with cries of "What about the Dardanelles?"

We have to admit it. Winston didn't like to admit mistakes. And he knew that the best defense was always a stronger offense.

The Battle of Gallipoli, Winston said, just appeared to be a massive [foul]-up. Instead, it was really the best thing that could have happened in the long run.

"The Dardanelles," Winston boomed, "might have saved millions of lives." "Don't imagine," he added, "I am running away from the Dardanelles. I glory in it."

Whether the Dardanelles saved millions of lives or not and showered Winston with glory (most historians doubt it), in July 1917 he was appointed Minister of Munitions. This was, as it sounds, the official in charge of making sure the armies got the weapons they needed. And one of the best weapons Winston could think of was the United States.

But getting the US involved would take some doing since the US president, Woodrow Wilson, had campaigned on a promise to keep his country out of the war. There was, though a new facet of this war that had never arisen before. That was the use of the submarine, and this new weapon gave Winston an idea.

Woodrow Wilson

A Campaign Promise

Winston knew that the Germans, well aware of American industry and prosperity, wanted to keep America neutral. But with the ramping up of underwater warfare, there was an increasing danger that American ships would indeed get sunk.

There's no doubt what Winston's intentions were. He wanted the Germans to attack merchant and even passenger ships from America. This isn't just liberal falderol revisionist speculation. There are actual memos where Winston stated that he wanted American ships to cross the Atlantic to Britain - and this is a quote - "in the hope especially of embroiling the United States with Germany." And to do so, Winston decided to stretch the rules of war.

Despite what many Americans think the Lusitania was not an American ship nor did its sinking bring America into the war. And we know today that the cargo of the Lusitania did include munitions.

But the arms it carried - several hundred cases of bullets and shrapnel shells and casings - were not necessarily sufficient to justify a ship being sunk without warning. But when the submarine encountered the Lusitania, the German commander had not followed proper protocol between a belligerent encountering a civilian vessel of the enemy.

The proper procedure would be for the attacking ship or submarine to intercept the ship and order it to heave to. A boarding party would then inspect the cargo. If war matériel was found, the passengers and crew would be evacuated to lifeboats, and the ship could then be seized or sunk.

People tend to roll their eyeballs and say no one would follow such a crazy protocol. However the procedure was observed routinely. During the first part of the war 70 % of the ships sunk were done without loss of life. The German Captain Count Felix Von Luckner kept to the rules rigidly. During the war he sunk a number of American and British ships - but without the loss of a single life or injury on either side.

Felix, though, found he did have unexpected difficulties. Once the owner of an American ship was taken on board and with him was a comely young lady. The lady, as you no doubt guess, was not the man's wife, who had remained home. The man expressed his concern to Felix.

"Could you leave my - uh - lady friend out of your official report?" he asked.

"By Joe," Felix replied (his strongest oath), "my superiors would not be too pleased either to know I had taken a woman on board - after all, this is a ship of the Imperial Navy. So if you will keep your mouth shut, I'll certainly do the same."

If the Germans continued to follow such a gentlemanly procedure, Winston realized, Woodrow would never declare war. So Winston insisted that British ships - civilian or otherwise - should ignore orders by submarines or ships to halt for inspection. If they did, the captains would be court-martialed (it was war and so merchant captains were subject to military law).

Winston also ordered that even British merchant ships were to be equipped with weapons. They were to resist any German attack, and if the ship was of sufficient size, it was to ram the sub.

If that wasn't bad enough - for the Germans - the British ships would sometimes fly flags of neutral nations - including the United States. So if a submarine commander saw a ship with the Stars and Stripes, it might be an armed British ship with orders to fight back.

The British, the Germans said, were flagrantly violating the rules of war. So it was they who had to accept responsibility for any loss of American ships or civilian lives. The British on the other hand snorted that the Germans were full of it. Nothing the British were doing went beyond a legitimate ruse of war.

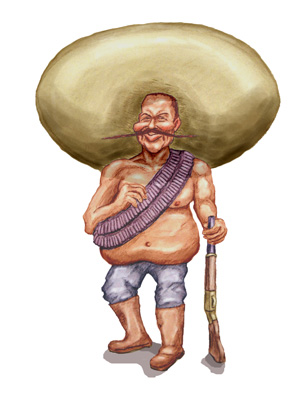

Pancho Villa

A Big Help for Winston

For the moment stymied, the Germans halted the unrestricted targeting of ships. They were particularly careful to avoid ships with the American flag. So it looked like Winston's strategy was falling flat.

But then Winston had some help. And from south of the border. The American border, that is.

On the night of March 9, 1916, a Mexican revolutionary, José Doroteo Arango Arámbula had entered the United States with 600 men. Calling himself General Francisco "Pancho" Villa, he moved three miles north and attacked the small town of Columbus, New Mexico. Pancho's target was the munitions kept at Camp Furlong at what is now - get this - Pancho Villa State Park.

The importance of the attack from a military point of view was negligible. Pancho not only failed to capture any weapons, but during the attack he burned the town and killed 18 Americans. Ten of the fatalities were civilians.

Of course, no American President could sit back and ignore the first attack on American soil since the War of 1812. So officially with the (nominal) consent of Mexican President Venustiano Carranza, Woodrow sent General John "Black Jack" Pershing after Pancho. Black Jack, who earlier had a photo-op with the smiling affable General Villa, entered Mexico with an army.

Called the Mexican Punitive Expedition, the troops entered Mexico on April 15, 1916. With the army fortified with state-of-the-art equipment including machine guns, automobiles, trucks, and the newfangled airplane, Black Jack spent the next ten months futilely looking for Pancho. Finally on January 28, 1917, Black Jack called it quits and returned home with nothing to show for his efforts.

Because Woodrow had been so inept trying to catch a two bit bandito, the Germans decided the Americans were a bunch of military stumblebums after all. The day after Black Jack pulled out of Mexico, Germany announced it would resume unrestricted submarine warfare. This though did not yet tip Woodrow's hand.

What was the drop that burst the dam was the so-called Zimmermann Telegram. This was a note from German Foreign Minister, Arthur Zimmermann, to the German Minister in Mexico, Heinrich von Eckardt. Arthur told Heinrich if Mexico joined Germany's side, Germany would make sure that Mexico got back all the land in the American Southwest the gringos had taken in the previous century. The British intercepted the message and handed it over to the US government, who immediately released the details to the press.

American sentiment now turned totally against Germany. On April 2, 1917, Woodrow asked for a declaration of war, and on April 6, he got it. The troops went "over there", and on the 11th hour of the 11th month and the 11th year after 1907, the warring countries signed an armistice.

Good Guy Winston

World War I saw the beginning of modern warfare. This means it was not only the first war to produce tens of millions of deaths, but ironically it was also fought under an increasing collection of official conventions and treaties designed to wage war more humanely.

The problem is that agreements about the way to fight a proper war tend to be specific regarding known technology. Methods that haven't been invented yet are naturally not included. And if not specifically forbidden, then must be all right. And that applied to chemical weapons.

The first significant use of poison gas in a major military assault was undoubtedly the German attack at Ypres in April 1915. The forces of Kaiser Bill fired artillery shells containing pressurized chlorine which upon bursting released the chlorine as a gas. Chlorine gas is of course extremely irritating, painful, and deadly. Later the even more toxic phosgene was employed.

The British first denounced the chemical weapons as a "cowardly form of warfare". They then readily adopted it themselves. After a while everyone was firing shells filled with chlorine. This included the Americans whose first use was allegedly from an artillery battery commanded by a nearsighted captain from Missouri named Harry Truman.

And Winston?

Recently it's become fashionable to trash Winston because he waxed most enthusiastically about using - in his own words - "poison gas". To read some of the criticism you'd think Winston took great pleasure in thinking about Britain's enemies dying with seared lungs and burned out eyes.

Of course, Winston's fans are having none of it. If you just read Winston's full words, they say, and not just snippets craftily qualified by a bunch of bleeding heart (ptui) revisionists, you'll realize he was talking about using an incapacitating gas. This was, Winston said, far more humane that having shells explode among the soldiers with shrapnel flying everywhere. Or as Winston actually put it:

I do not understand this squeamishness about the use of gas. We have definitely adopted the position at the Peace Conference of arguing in favour [as Winston spelled it] of the retention of gas as a permanent method of warfare.

... and ...

Why is it not fair for a British artilleryman to fire a shell which makes the said native sneeze? It is really too silly.

Winston knew very well that these weapons did much more than make the enemy sneeze. Nevertheless Winston's friends point out what he advocated was diphenylaminechlorarsine which indeed has been used as a non-lethal tear gas to disperse rioters. Among the "riots" where it was deployed was in the 1930's when American veterans of World War I had marched on Washington.

That Winston specifically called for the use of "debilitating", not deadly gases has further support from his writings:

It is not necessary to use only the most deadly gasses [Winston's spelling]: gasses can be used which cause great inconvenience and would spread a lively terror and yet would leave no serious permanent effects on most of those affected.

In World War I the most common so-called "incapacitating gas" was mustard gas. And Winston's friends will point out that fatalities with this gas were minimal, in the low single digit percentiles.

Now if you only count short-term deaths by this - quote - "weapon" - unquote - the number of fatalities can indeed be toted up as single digit percentages (although 90,000 deaths out of 1,000,000 gas casualties scarcely seems low).

But today when attributing a fatality to an exposure there are no limits on the time from the incident to the date of death. And among the survivors of mustard gas were people who suffered horrendous wounds to the skin, eyes, and lungs, resulting in life long debility and premature death. By using the longer term criteria, some estimates are that during the war hundreds of thousands of people - double digit percentiles - died from chemical weapons and most the injuries were from "sulfur mustard".

Winston certainly had no opposition to mustard gas. Even during World War II - twenty years later and after chemical weapons had been banned - he called on the military to consider use of mustard gas against the Germans.

I want a cold-blooded calculation made as to how it would pay us to use poison gas, by which I mean principally mustard.

And Winston doesn't want any morality arguments by squeamish goody-two shoes:

It is absurd to consider morality on this topic when everybody used it in the last war without a word of complaint from the moralists or the Church. On the other hand, in the last war bombing of open cities was regarded as forbidden. Now everybody does it as a matter of course. It is simply a question of fashion changing as she does between long and short skirts for women.

Winston was even willing to turn chemical weapons onto civilian populations. As he put it:

I may certainly have to ask you to support me in using poison gas. We could drench the cities of the Ruhr, and many other cities in Germany in such a way that most of the population would be requiring constant medical attention.

Naturally, Winston's friends will point out he is simply asking for a feasibility study. He definitely stated he did not want to use chemical weapons unless it was a matter of life or death or that it would shorten the war by at least a year. Winston was not in favor of hasty action.

It may be several weeks or even months before I ask you to drench Germany with poison gas, and if we do it, let us do it one hundred per cent.

But ...

If you're at the stage where you need to do something as a "last resort" that means you've lost the fight. And Winston's continued interest - some say his bulldog bullheadedness - with chemical weapons seems strange given the sound and practical reasons that they were quickly banned. Still, say what you like. For all his advocacy and interest, in World War II Winston never authorized use of chemical weapons at any time.

Winston Inter-Bella

After the war, David Lloyd George appointed Winston as the Secretary of State for Air and War. In this capacity Winston was present in Paris during the peace talks. One of his jobs was to negotiate the shape of the New World Coming.

Everyone knows that the various peace treaties (yes, there wasn't just the Treaty of Versailles) did not produce the desired goal of preventing Germany from rearming. But remember that Germany wasn't the only country that fought against the Allies. And one of Winston's most important tasks - particularly when he was appointed Colonial Secretary in 1921 - was determining how to divvy up the now defunct Ottoman Empire.

You see, when England had to pull out of Gallipoli, the British decided they would have to beat the Ottomans by moving up from Egypt. And they also realized there was an untapped source of men who might fight on their side.

So they sent feelers to the leader of the Arabian region called the Hijaz. This is the strip of land along the west coast of the peninsula and includes the religious cities of Mecca and Medina.

The leader of the Hijaz was called the Sharif and at the time this was Hussein bin Ali. His family - the Hashemites - had ruled the Hijaz for many generations. Knowing that Sharif Ali had a lot of clout with Arabs in general, the English envoys asked him if the Arabs - linguistically and ethnically separate from the Turks - would revolt against the Ottoman Empire.

Sharif Ali said yes - on the understanding that a victory of the Allies would lead to independent Arab countries. They were not interested in just becoming new subjects of another foreign power. To what extent the British explicitly agreed to these terms has been a subject of historical debate. But whatever agreement was made, the Arab leaders believed that a committment to Arab independence had been made. In any case, the British began sending arms and supplies (not to mention money) to help support Arab armies.

One of the armies was led by Ali's son, Feisal (also spelled Faisal). Among the British officers sent to work with Feisal was a young intelligence officer who had been stationed in Cairo. This was, of course, Captain Thomas Edward Lawrence, called "Ned" by his friends.

T. E. Lawrence

Ned to His Friends

Although Ned has been trashed by some historians as a show-off and fabricator, what he did required considerable courage. He was actively involved the destruction of the Ottoman railways, gathering intelligence, and was present at major Arab military actions (during one where he accidentally shot his camel and was thrown to the ground). He was often out of uniform and was so subject to being captured and executed as a spy and saboteur, which, of course, he was.

Based on correspondence with Sir Henry McMahon, Sharif Ali believed the Arabs would indeed be able to set up their own countries. What he didn't know was that Britain and France had already signed what became known as the Sykes-Picot Agreement.

Briefly the Sykes-Picot agreement stated that the two countries would allocate the Middle East between them. England was to keep Egypt and the historical region of Palestine. France, in turn, would get Syria - then occupying a more extensive area than today. As what to do with regions further west in historical Mesopotamia, well, they'd decide later.

Officially Ned was a liaison to the Arabs, but he did more than just transmit messages back and forth. The value of his work was recognized when he was made a Companion of the Order of the Bath and awarded the Distinguished Service Order medal. The French even awarded him the French Légion d'Honneur - a distinguished award indeed and which has been granted to other notables like Miles Davis, Quincy Jones, and Jerry Lewis. Ned was even offered a knighthood which he declined (his tailor would double his bills, he said). On the other hand, he was unknown to the public and no one saw his exploits going beyond what other capable soldiers and officers had done.

No one that is except for an American reporter and sometime college instructor named Lowell Thomas. Lowell and his cameraman Harry Chase had been covering the war with US State Department approval but with private financing.

Lowell had first gone to Europe but found little that would make good copy. So he switched to the Middle Eastern theater where British Field Marshall Sir Edmund Allenby had just occupied Jerusalem. Lowell asked for an interview with Sir Edmund and was surprised at the congenial reception he received.

Lowell also managed an interview with the military governor of Jerusalem, Colonel Ronald Storrs. During the meeting Lowell mentioned he had been hearing rumors of a "desert fighter" who was not an Arab but was working with them.

Ronald walked to a side door and opened it. There was Ned, dressed in Arab garb, waiting in an anteroom. Ronald said, "I want you to meet the Uncrowned King of Arabia." Ronald, who had know Ned at college, was cracking a joke.

Lowell got permission to travel to Lawrence's camp at the port town of Aqaba in modern Jordan. He and Harry Chase spent ten days in Arabia and were able to be with Ned for two. After a side trip to Petra, both men returned to Europe.

Then suddenly the war was over. After sneaking into Germany - then in the throes of a number of ill-defined and short-lived revolutions - Lowell returned to America. He and Harry now had plenty of film and photographs. The question now was what to do with them.

Lowell Thomas

Two Days with Ned

In the 19th century a popular way to spend a night out was to attend lectures presented by famous journalists, novelists, or other celebrities. Later these lectures were often "illustrated" by projecting still photographs onto a screen - the well-known "magic lantern" show.

Then in the late 1890's, there came the invention of two brothers from France. Instead of showing single images on a screen, they rapidly projected sequential pictures so rapidly that there was the appearance of actual motion. These Cinèmatographs Lumière could be viewed by an large audience sitting in a theater, not just by a single viewer hunched over a kinetoscope.

So by 1918 there was the technology to put on what we would call a "multimedia event". Lowell's show, The Last Crusade: With Allenby in Palestine and Lawrence in Arabia, was one of the turning points in modern entertainment. A true extravaganza, the show was narrated with Lowell's unique vocal skills and illustrated - often simultaneously - with both still photographs and motion pictures, all handled backstage by Harry. There was also a live Oriental orchestra and a veiled dancing girl (who in one performance was Lowell's wife, Fran). With Allenby in Palestine and Lawrence in Arabia was a smash hit and played to packed theaters in America.

That Americans knew of an English war hero who was totally unknown to the British public was an irony not lost on the English impresario, Percy Burton. Percy saw the show in New York and immediately signed Lowell up for a run in London's Albert Hall. The show was as big a hit in Britain as it had been in America. Everyone had to see it, and that included the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George. He attended a performance with all his cabinet in tow. That, of course, included Winston.

To say Winston was impressed with Ned - now dubbed "Lawrence of Arabia" by the media - is a bit of an understatement, and later one of his friends said Winston's attitude was near hero worship. It was no surprise, then, that in 1921 Winston asked Ned to be an advisor on Arab affairs.

There were some officials in the government who agreed that promises for Arab independence should be honored. But others were d'accord with the Balfour Declaration which supported establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine.

Ned, though, saw no conflict. Before the war, he had traveled through the Middle East and had been impressed with the Jewish settlements of Palestine that were developing the land for farming and industry. You could help Arabs achieve independence, Ned believed, and also implement the Balfour Declaration.

He was not alone in his thinking. Even Faisal, Sharif Ali's son, stated he understood Zionist aspirations. He later met with the chemist and Jewish leader Chaim Weizmann and the two men agreed that they should work together.

Notice that everyone was talking and agreeing, but no one really had defined any terms. What constitutes a "homeland"? What is "independence"? Did both terms mean establishing fully separate countries? Was it sufficient to establish a dominion within, well, a larger entity like the British Empire?

Don't worry about it, said the Arab leaders who met in Damascus. We've taken care of everything. They declared Feisal the king of "Greater Syria". This was a new and independent country that included present-day Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and Israel.

A Jewish homeland? Well, we'll see.

The independent Arab kingdom of Greater Syria lasted about a millisecond. It vanished as soon as France and England called in the Sykes-Picot Agreement.

Hm. So what to do now? Britain and France now had millions of new subjects who 1) didn't want to be subjects of European powers, and 2) felt they had been deceived by their new rulers. This is not a good prescription for a stable happy Empire.

So Britain and France had to give in somewhere. And they hadn't yet divvied up Mesopotamia. So why not set Feisal up as king there? After all, that region contained the fabled city of Baghdad. Now the Allies could say they had given Arabs independence and could still hang onto Egypt and the lands of the eastern Mediterranean. Although not exactly happy with the arrangement but knowing he had no choice, Feisal agreed.

Briefly, then, the idea was that Britain would continue to occupy Egypt. They would also have a "mandate" of Palestine with the idea of forming a Jewish state. France would keep Syria. The idea of having a separate country for the Kurds was discussed but soon scrapped.

Next, the Arabian peninsula would remain a collection of independent Arab countries - England and France both knew that even nominal attempts at control of those regions would be a total disaster. Feisal would be King of Mesopotamia - which was reshaped and renamed as Iraq (or Irak as it was first spelled). Feisal's younger brother, Abdullah, would become king of a country west of the Jordan River. As it was across (Latin: trans) the Jordan, the country was first called Trans-Jordan. With this all done, Lawrence left the Colonial Office to return to private life.

Of course, things didn't quite work out as planned. After more than twenty years of finding it impossible to implement the Balfour Declaration, the British just up and pulled out of Palestine. That left everyone to sort things out for themselves.

In any case, Winston maintained his high regard for Ned. The two men became good friends, and once Ned just showed up at Winston's home and helped him lay bricks for a garden wall. Their friendship only ended in 1935 when Lawrence died following a motorcycle accident. Winston attended the funeral.

Winston Go Braugh!

But while England and the Winners of the War were cutting up the Middle East, there was a problem much closer to home.

Although originally agin' it, Winston had later backed Home Rule for Ireland - including the six counties up north in Ulster. World War I, though, had put a hold on the plans. But after the war, England promised, we'd get things moving.

But for some Irishmen that wasn't good enough. So in the midst of the war and on Easter Monday, 1916, a group of Irish militiamen - nominally organized for protection of the communities and under the command of Patrick Pearse - seized the General Post Office Building in Dublin. Additional Irish militia seized other locations, including a cookie factory. The leaders then declared Poblacht na hÉireann, an independent Irish Republic.

After a siege of a less than a week, the British forced the Irish to surrender. Military courts sentenced ninety of the "rebels" to death. However, by the time the first fifteen men had been shot, the public sentiment, which originally had turned against the rebellion, underwent a strong reversal. The rest of the prisoners were just jailed.

In 1917 and bowing to increased international and domestic pressure, Britain granted an amnesty to the remaining prisoners. They immediately took up arms again. Calling themselves the Irish Republican Army - the IRA - they began fighting the British with the purpose of achieving full independence for a thirty-six county Ireland.

Eamon De Valera

The President of the Republic

From 1919 to 1921, there was a full blown war in Ireland. By then Winston been appointed Secretary of State for War and Air (the equivalent of America's Secretary of Defense). Rather than send in regular army soldiers to Ireland, Winston conceived of having a special force. Officially called the Royal Irish Constabulary Special Reserve and informally dubbed the "Black and Tans" (after the style of their uniforms), they were a paramilitary organization that even today raises much controversy.

By 1921 the head of the Black and Tans, General Frank Crozier, had resigned because of the behavior of the men. The Tans, he said, "used to murder, rob, loot, and burn up the innocent because they could not catch the few guilty on the run". Remember this was a British general talking. When a member of the Tans was killed in Cork, his comrades burned down 300 buildings in the center city.

But it wasn't just Black and Tans Out of Control that caused increased anti-British sentiment. The government - remember that Winston was the Secretary of Air and War - authorized reprisals which included burning property of IRA suspects and their supporters. Captured IRA men were sentenced to death and executed. In turn the IRA began retaliatory executions of captured British soldiers, whether they were Black and Tans or regulars.

Clearly something had to be done. One of the militia leaders of the 1916 Rebellion was the American born, Eamon de Valera who had emerged as the Irish leader. After the 1917 amnesty he had been re-imprisoned, allegedly for plotting against the Crown. But he managed a well-publicized escape and headed off to the United States. There he raised considerable funds to fight the British and was being touted as the head of the Irish Republic.

After eighteen months in America, Eamon returned to Ireland to be promptly re-arrested and then almost immediately released. He was then handed a letter from David Lloyd George asking to come over and talk about "Irish aspirations".

But when Eamon got to England he found the British were offering nothing more than Dominion Status. Ireland would have its own parliament but nonetheless would remain subordinate to England. Foreign affairs would be handled by England, and all Irish citizens would take an oath to the Crown.

But worse (to Eamon), the six counties of Northern Ireland were not to be included. So after all the bloodshed, what the British offered was nothing more than Home Rule Without Ulster.

Eamon saw the English weren't going to budge. He also knew that the Irish people were weary of war and would be quite happy with the English offer.

Trapped between the rough surface of the Blarney Stone and the wet banks of the Boyne, Eamon sent Michael Collins, who had been the head of the guerilla operations of the IRA, and Arthur Griffith, the founder of the Sinn Féin political party, to do the negotiating. He, Eamon, remained in Dublin and sat on his emerald green thóin. That way when the final treaty granted Ireland - yes, Home Rule Without Ulster - Eamon could be shocked! shocked! that Michael and Arthur would cave in to the British demands.

Well, that's what happened, and Eamon led the IRA in a renewed war, not against the British, but against the new Irish Free State Army. Neither Arthur nor Michael survived this brutal and bitter Irish Civil War, Arthur dying of a massive stroke on August 12, 1922, and Michael shot in ambush by the IRA ten days later at Beal na mBlath in County Cork.

Winston was now Secretary to the Colonies. So it made sense that he would have been at the negotiating table to hammer out the Anglo-Irish Treaty. Later Michael claimed that the treaty would have been impossible without Winston.

At first, though, Winston hadn't been that happy to be sitting down at a table with the notorious Michael Collins since it had been Michael who had engineered various assassinations, including the 1920 "Bloody Sunday" massacre of 10 British officers in Dublin. Likewise Michael wasn't too happy working with Winston who was part of the government that ended up executing a number of his friends.

But eventually the two men found common ground. At one point the negotiators had taken a break and were sampling the good whiskey that both Michael and Winston favored. Fueled by the liquor, Michael and Winston became increasingly belligerent until Michael finally yelled that Winston had placed a £5000 price on his head. Winston then led Michael over to a framed paper on the wall. It was a wanted poster for Winston from the Boer War where he was wanted dead or alive - for £25. At least he, Winston, had made an offer commensurate with Michael's notoriety. Michael broke out laughing.

Michael Collins

A Commensurate Offer

The Anglo-Irish Treaty became effective March 31, 1922. Six months later the Prime Ministership of David Lloyd George came a-tumbling down. Historians give a number of reasons for David's loss, but it certainly didn't help when word got out he had been bestowing favors - including wrangling titles of nobility - in exchange for cash. This might not have been a problem except that David's government - although officially Liberal - had actually been a coalition with the Conservatives. So the Conservatives withdrew, and no longer with a majority, David's government fell apart.

The next government was under the Conservative MP Bonar Law (that was his name, not a misprint). Bonar didn't last long (no wisecracks, please) and was replaced six months later by another Conservative government under another famous Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin.

And Winston?

As we said, Winston was no doctrinaire party follower. He had sentiments of both the Liberals and Conservatives and would vote the way he thought was best. So he was not only willing but welcome to join Stanley's government. First, of course, Winston also had to get elected.

This wasn't easy. Winston lost the 1922 election in Dundee and also the 1923 election in Leicester (pronounced "Lester") which was actually in England. He tried again for Westminster Abbey and once more lost.

It seems that in 1920's England being a Liberal was no more popular than in the 21st Century United States. So in 1924 Winston ran as an independent candidate for Epping, a town which is close to the mouth of the Thames. He won, but Winston wasn't fooling anyone. He had been sliding toward the Conservatives more and more, and so once elected he rejoined the party.

Stanley appointed Winston as Chancellor of the Exchequer. As a Conservative and in charge of the country's finances, Winston then decided he needed to return to Basic British Family Economic Values.

There was to be no more of this modern economics claptrap where the pound was based on the productivity of labor. None of that mixed-metal nonsense either. Instead, the Empire would only regain it's war-sapped economy by the return to the Gold Standard. Yes, good old fashioned English gold.

Boy, did Winston blow that one. Setting the total capital of a country based on how much of a single metal you have in your vaults sounds good, but doing so actually limits the ability to increase productivity. Unless you can get more gold (not easy) the economy is always robbing Harold to pay William, and this works only temporarily. And if the limited money supply gets concentrated into only a few sectors - like the pockets of the rich fat cats - there is less and less money available for those piddly-ant expenses like paying wages and establishing new businesses.

Unemployment soared, the pound tanked, and the miners all went out on an unsuccessful strike. In less than a year Stanley's government was gone.

For the next decade England kept flopping between Stanley and Ramsay MacDonald. The reason why the country kept playing Musical Prime Ministers is actually pretty easy to understand. There was not only a Great Depression in the United States, but pretty much worldwide. That included England. And when it was evident that one group wouldn't fix the economy, then the voters would try again with the other.

Three Sticky Wickets and Winston was OUT!

And Winston? You'll read that for much of the late 1920's and the 1930's Winston was "out of office." But in Britain that doesn't mean the same thing as in  . Saying Winston was out of office just means he didn't have a fancy cabinet post. That doesn't mean he wasn't in Parliament. And for more than 20 years - from 1924 to 1945 - he represented Epping. But for now, 1929, Winston was out as Chancellor of the Exchequer.

. Saying Winston was out of office just means he didn't have a fancy cabinet post. That doesn't mean he wasn't in Parliament. And for more than 20 years - from 1924 to 1945 - he represented Epping. But for now, 1929, Winston was out as Chancellor of the Exchequer.

In fact, from 1930 to 1939 Winston held no cabinet posts at all. Also being an MP back then was not as onerous and time consuming a task as it is today. MP's would go for some time and not even bother to show up in Westminster. So during the 30's Winston spent a lot of his time writing books and articles.

Why Winston repeatedly got a cold ministerial shoulder is like a doctor's prescription, a combination of ingredients. There was Gallipoli. There was Gold Standard. And the third of the active ingredients, the third sticky wicket that sidelined Winston, was the idea that India should remain a colony firmly in control of the British Raj.

Taking Gandhi from the Crazies

Mahatma Gandhi

Winston had no doubts.

You'd think the deal with Ireland would have sent Winston a message. That is, when the people of a country want to run things themselves, ultimately you have to accommodate them. Keeping an unwilling populace under your thumb just isn't worth the trouble.

But mention Home Rule for India and Winston would have a cow. That's not a surprise, Winston's detractors snort. They take particular delight in reminding the world that Winston's rants against Indian Home Rule included not just horrible comments about the Indian people but also included repeated vituperations against an English educated lawyer named Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi.

Now if you really want food for an argument, look up some of the more, well, "interesting" facts about the Mahatma (a title meaning "Great Soul"). Today he is one of the most revered figures throughout the world, true. But his strange quirks - and we mean strange - have become food for discussions, particularly his amorous life or lack thereof. At nearly 40, he decided on a life of spirituality which meant he would test his resolve by having comely young ladies sleep next him at night. We wonder how often his spiritual strength failed him.

Oddly enough, the Mahatma was not originally anti-British and would have been happy for the country to remain in the Empire. But what he wanted was the English to recognize the Indians as true citizens with full civil liberties. Instead the English had set up a system where the native population was treated largely as serfs who had to buy necessities at inflated prices from state run monopolies. Even salt, a basic foodstuff, had to be bought. Possession of home-made salt - or any salt not purchased from the state - was a crime.

Before the First World War, the Mahatma had made a reputation for fighting for the rights of Indians - but in South Africa where he had lived since 1893. Returning home in 1914 at age 45, he urged the Indians to join Britain in fighting against the Germans. That would prove their loyalty to the Crown and lead the way to more equality.

Well, it didn't turn out that way. Almost as soon as the war was won, on April 13, 1919, a large group of unarmed Indians - both Hindus and Muslims - had gathered in the town of Amristar in the Punjab in the north of the country. They were protesting the arrest of two leaders of the Indian National Congress, a group originally organized by a Scotsman to represent Indian interests. However, by the 20th century the organization had shifted gears and with increasingly strident demands had made the British very nervous. When he got back from South Africa, the Mahatma became one of the National Congress's leaders.

At Amristar the Indians were unarmed but there were a lot of them. This made the local army commander, Colonel Reginald Dyer, nervous. Reginald, to put it midly, was a real jerk. He called in troops and ordered them to start firing into the crowd and kept firing at the exits as people tried to escape. The troops kept shooting until their ammunition was exhausted. Officially there were 379 people killed although other estimates are that it was closer to 1000.

At this point the Mahatma saw that the only solution was Indian independence. Here we see the Mahatma as we know him, the elderly advocate of non-violent resistance, walking with the crowds, sitting at the spinning wheel, and walking 300 miles to the beach of Dandi to make salt.

No one quite knew what to make of the Mahatama. Newspapers covered his doings, he appeared in newsreels, and in 1930 he even made Time Magazine's Man of the Year (now more correctly dubbed Person of the Year).

Winston, though, had no doubts about the Mahatma. He was just a big phony. As Winston put it:

It is alarming and also nauseating to see Mr. Gandhi, a seditious Middle Temple lawyer, now posing as a fakir of a type well known in the east, striding half-naked up the steps of the Viceregal Palace, while he is still organizing and conducting a defiant campaign of civil disobedience, to parley on equal terms with the representative of the king-emperor.

And when the Mahatma was arrested for causing "sedition", he would go on hunger strikes. Winston was not impressed and advised:

Gandhi should not be released on the account of a mere threat of fasting. We should be rid of a bad man and an enemy of the Empire if he died.

The Mahatma's purpose, Winston saw, was to pluck out the Jewel of the Empire leaving the English with only the brass.

Gandhi stands for the expulsion of Britain from India. Gandhi stands for the permanent exclusion of British trade from India. Gandhi stands for the substitution of Brahmin domination for British rule in India. You will never be able to come to terms with Gandhi.

Winston finally summarized his views succinctly:

Gandhi-ism and all it stands for will, sooner or later, have to be grappled with and finally crushed.

Here Winston was really off-base, not just with reality, but with the sentiment of his country. Throughout the 1930's a large number of working class Britain loved the Mahatma. Although the English authorities kept tossing him in jail, in 1931 and bowing to the inevitable, the government let him attend discussions on the future of India (called the Round Table Conferences). No solution was forthcoming, but photos were taken of the Mahatma surrounded by adulating crowds and him the rubbing elbows with popular celebrities like Charlie Chaplin.

One problem with Winston's diatribes against the Mahatma was that they were so extreme. After a while he began to sound like a broken record (for anyone who doesn't understand this allusion, ask your grandparents). Winston's rants began to go stale and so no one was listening when he turned his rhetorical guns against a new politician from the Continent who had just hit the big time.

The Other Politician

Almost as soon as the grandson of Maria Schicklgruber was appointed chancellor of Germany in 1933, a fire in the Reichstag transformed the government from a freely elected democratic republic to a terroristic state dictatorship. Germany was soon on a wartime economy, which explains why Germany was one country that weathered the 1930's fairly well.

Winston did not like what he saw in Germany: the Nuremberg Laws, the concentration camps (first established in 1933), and German rearmament. And yet Winston also had a life long antithesis of the Bolsheviks, who were outspoken enemies of Fascism. It's no surprise, then, that the 1930's gives both Winston's fans and his detractors plenty of out-of-context quotes to fling back and forth.

Today most people can't believe the world didn't see Hitler as the genocidal maniac he was and wonder how the world let the madman go as far as he did. But remember the world of 1935 - before the Anschluss, before Kristallnacht, before the Endlösung - often saw Hitler as a clownish buffoon, someone to laugh at and who would throw tantrums and chew the carpet.

There are also contrarians who are quick to point out that even the Mahatma seemed to go soft on Adolph. After all, look at his now famous letter - here heavily edited - written as late as 1940.

Dear Friend,

That I address you as a friend is no formality. I own no foes.

We have no doubt about your bravery or devotion to your fatherland, nor do we believe that you are the monster described by your opponents.

I am,

Your sincere friend,

M. K. Gandhi.

This is more or less what you might read in the "What You Didn't Know About Gandi" articles. Huh! Great Soul? Not bloody likely!