A Most Merry and Illustrated History

of the

Sad Life and Tragic Death of Edgar Allan Poe

October 3, 1849 - Rather the worse for wear

Rather the Worse for Wear

On October 3, 1849, at 9 o'clock in the morning, Mr. John Walker was strolling along Light Street Wharf in Baltimore when he happened on a group of men clustered around a building which housed Ryan's Tavern. Lying across the bench was a slightly built and dark haired man, clad in torn and ill-fitting clothes. Walker himself was a printer and typesetter who had previously worked for the Baltimore editor and physician, Dr. John Snodgrass, who in turn was a good friend of the poet and author Edgar Allan Poe.

So Walker was flabbergasted to find it was the famous writer himself who was sprawled out on the bench. He tried to question Poe, but the author was barely conscious. About all Edgar could remember was his name and that he knew Dr. Snodgrass. So Walker dashed off a quick note telling the physician he had found Poe in the street "rather the worse for wear" and that the gentleman needed immediate assistance. Then, possibly with the help of the other men, he managed to bundle Poe into the tavern.

Dr. Snodgrass arrived in the afternoon, and found Poe with Henry Herring, one of Edgar's Baltimore uncles. Poe was indeed the worse for wear and the men concluded Edgar had finished up one of the periodic binges which had been a continual thorn in the side of his friends and relatives. Of course, they weren't all that good for Edgar either as the present circumstances certainly seemed to show.

After the men moved Edgar upstairs to one of the rooms, Henry suggested that a hospital would be better than a tavern. Dr. Snodgrass replied that the house of a relative - Henry's - might be better than a hospital. That was probably true. Serious illness in the early nineteenth century could usually be treated at a private home as effectively as in a hospital. Given the state of medicine at the time, you either recovered by yourself or died, and a home was as good a place for either. Hospitals were largely places to go for people who had no home and no place to go.

But as Snodgrass told it, Henry balked. When Edgar was in his cups, Henry said, he could be abusive, belligerent, and "ungrateful" to the members of his household, including the women. Snodgrass was at first a bit irritated with Henry, but then saw that a hospital would probably be the best thing. The men ordered a carriage and carried their now virtually comatose friend outside. Soon Edgar found himself under the care of Dr. James J. Moran at Washington College Hospital.

Dr. Moran's accounts - as did Snodgrass's - seemed to improve with the telling. In both an "official memorandum" written eighteen years later and in a short booklet written another eighteen years after that, Moran reports Poe speaking in stately measured and poetic sentences, bemoaning his fate and folly. If the later accounts are to be believed, Dr. Moran also did not follow recommended bedside manner when dealing with a confused and distraught patient. Instead he began giving Poe apocalyptic warnings about his impending demise. At that point, Dr. Moran told how Poe recited an impromptu multiverse poem and practically gave a stump speech that eclipsed even the most flamboyant oratory of the Lincoln-Douglas debates which lay a decade in the future.

Edgar bemoaned his folly

It was also in his later accounts that Dr. Moran hastened to add that despite what others had said there had been no evidence Poe was suffering from intoxication. There was no smell of liquor about him nor any signs of violence. So the idea that Poe was a victim of alcoholic misadventure, he assured posterity, was not true.

Unfortunately (especially for Dr. Moran's historical credibility) one of his friends later said that Dr. Moran's later writings ran exactly 180 degrees contrary to what he had said at the time. But we don't have to worry about the credibility of Dr. Moran's buddies. Within a month of Edgar's death he wrote a highly detailed account to Maria Clemm, Poe's aunt. In the letter he stated bluntly that he presumed Mrs. Clemm already knew about the "malady" from which Poe died.

With Poe's medical history and reputation, the only "malady" Dr. Moran could be referring to was Edgar's problem with alcohol. For virtually all of his adult life, Poe had been struggling with the bottle. Although he could go through periods (he claimed) without drinking, it's also true he kept writing letters to family and friends how he was going to swear off. His friends frequently wrote each other about Edgar's "illnesses" at least some of which were clearly super-hangovers.

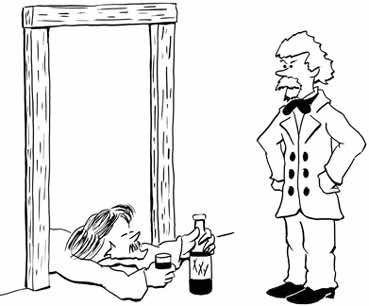

However, some admirers of Poe have claimed - then and now - that Edgar was not alcoholic per se. Instead, they say, his problem was an unusual sensitivity to alcohol. A single glass, they said, could have a devastating effect.

One glass could have a devastating effect

Now it is true there are medical conditions where individuals cannot properly metabolize alcohol and where drinking can lead to a buildup of toxic intermediates in the blood. For these people a single drink can indeed have serious and sometimes fatal consequences. So to paraphrase John Steinbeck, if such an excuse isn't true, it is at least plausible.

But an even more plausible explanation is that Poe, like many alcoholics, was simply able to hide the number and volume of his snorts. After arriving home from a bar and falling flat on his face, we can easily imagine him telling Mrs. Clemm and his wife Virginia that he had only had a drink or two. Or if his friends found him reeling about the streets of Richmond, Baltimore, or Philadelphia, it's more likely he'd claim he only had a glass of wine with his lunch rather than two or three bottles.

Historians tend to accept Moran's earlier letter as the more reliable account of Poe's last days. Not only because that's the number one rule for historians - the earlier the story, the better. But also that it just sounds better. Far from reporting that Poe spent his last couple of days declaiming Ciceronian oratory and Homeric verse, Dr. Moran simply told Mrs. Clemm that her nephew's answers to his questions were incoherent. He said Poe couldn't even remember how he got to Baltimore and he also claimed he had a wife who lived in Richmond. The last bit wasn't true; at the time Edgar had been a widower for over two years.

But what really seemed to upset Edgar was that he had encountered the worst fate that can befall any traveler. He had lost his luggage.

Poe's condition continued to worsen. He began hallucinating, or as Dr. Moran told it, Edgar held "vacant converse with spectral and imaginary objects" on the wall. At three o'clock in the morning, tremors developed in his arms and legs and he fell into (again in Dr. Moran's picturesque wording) a "busy delirium" - as if talking to the walls wasn't busy enough.

By morning, a number of Edgar's Baltimore family had learned about their famous relative's unplanned visit to their city. Neilsen Poe, a cousin (and Neilsen was his real name, not a misprint), showed up with some fresh clothes and sheets. But the doctors said Edgar was still too excitable for visitors. Later, though, they said they were able to "induce tranquility" and Neilsen heard that Edgar was much better.

Whatever the doctors told Neilsen, Edgar really wasn't improving. Sometimes he would give babbling answers to simple questions about family, relatives, and even where he lived. And whenever he might seem more lucid, his spirits would take a nosedive. At one point Dr. Moran said (and once more totally contradicting his later story) that he tried to cheer Edgar up and that he hoped Poe would soon recover. Poe then "broke out with much energy" and said that the best thing a friend would do would be to "blow his brains out with a pistol". He added that when he saw his "degradation" he was ready to "sink into the earth".

At this point, Dr. Moran left the room. When he returned, he found Poe again in a violent delirium "resisting the efforts of two nurses" to keep him in bed. This continued until Saturday evening when Poe, still delirious, kept crying out a name that sounded to Dr. Moran like "Reynolds".

Poe's condition remained unchanged until 3:00 a. m. Sunday morning (Reynolds, whoever he was, didn't show up). Then Edgar suddenly became quiet. He seemed to rest but far from indicating the beginning of recovery, his new condition was - as Dr. Moran pointed out - simply that Poe was now "enfeebled from exertion" and he just no longer had the energy to be violent. In fact, he didn't have the energy to do anything anymore. Around 5:00 a. m. Edgar said, "Lord, help my poor soul" and died.

He was buried two days later in Westminster Cemetery which was attached to Baltimore's Presbyterian Church. The actual number in attendance isn't known. Most authors say it wasn't many - half a dozen, perhaps; maybe eight. Still Dr. Snodgrass said he had requests from at least fifty ladies for a lock of Poe's "raven black hair"; requests, by the way, that would have been difficult to honor since Poe's hair was brown.

Poe's Raven Brown Hair

Mrs. Clemm read about Edgar's death from the newspapers. To say she was shocked, shocked is the understatement of the year. The last she heard Edgar was on a lecture tour getting money to launch a new magazine. The tour had been very successful; on one night alone Edgar might have garnered as much as $200 - big money at the time. Edgar had written her a letter on September 18 saying he was heading to Philadelphia and he said she should send her letters there. It's hard to believe, but at the time you could address a letter simply "Mr. E. Poe, Philadelphia" and it would get there. In any case Edgar was intending to stay a day or two in Philly and then head on up to New York.

Mrs. Clemm was shocked.

Like everyone else, Mrs. Clemm wondered how Edgar wound up in Baltimore a week after he left for New York. She immediately wrote to Neilsen asking what the heck had happened. He got the letter the next day (try getting a letter from New York to Baltimore that fast today) and wrote back at once. Neilsen was tactfully vague, but did give her the basics. At the same time Mrs. Clemm had written to Dr. Moran whose name she probably got from the papers. Dr. Moran didn't get the letter until November 14, and then he wrote the detailed letter that we have now.

So within a month of Edgar's demise, everyone - Snodgrass, Neilson, Moran, Herring, Mrs. Clemm and from the sounds of it, Edgar himself - believed Edgar Allan Poe had died from the results of a drunken debauch. Not only had Dr. Moran made the cryptic reference to Edgar's "malady", but he added that he preferred to "cancel [Poe's] errors than even hint a fault of his." So as far as everyone was concerned there was really no doubt about it. Edgar's weakness for the bottle had finally done him in.

The Real Story: Maybe, Sort of, or Maybe Not

The nineteenth century medical diagnosis for Edgar's death was mania a potu, or "madness from drinking". A more up-to-date diagnosis is he died of the delirium tremens or the DT's, the name given to a variety of symptoms that occur during alcohol withdrawal. Although it's most common in chronic alcoholics who abruptly stop drinking, the DT's can also occur after a serious short term spree.

The most overt symptoms of the DT's are delirium, tremors, seizures, and hallucinations. Patients sometimes become so violent that they may have to be restrained (as Edgar was). Less outward signs are fever, elevated blood pressure, and cardiac arrhythmias. The last bit is bad news. Depending on who you consult, you will read that untreated DT's have a fatality rate between 15 and 35 %.

All right. If we know how Edgar died, then why have historians, doctors, lawyers, popular writers, cartoonists, butchers, bakers, candlestick makers, and just about everyone else been debating how Edgar Allan Poe "really" died? For over 150 years, different theories have flown back and forth, new ones have been created, and old ones continuously recycled.

Today if we read about Edgar we're likely to learn that he died of injuries sustained during a robbery (a fairly early alternative), hypoglycemia (although it's rarely fatal), diabetes (which was very fatal in Edgar's time), hepatic porphyria (a condition where alcohol can trigger violent and again sometimes fatal reactions), or alcohol dehydrogenase deficiency (where alcohol's metabolic pathway stops at acetaldehyde rather than going all the way to carbon dioxide and water). Other theories include heart failure (which in one way or another seems kind of obvious), rabies, being waylaid by a new girlfriend's brothers, or being forced to vote. Another suggestion was Edgar died of carbon monoxide poisoning although most people don't even believe he had a car.

The Alternate Theories: Robbery, Rabies, and Voting ... Among Others

So why all the theories, especially if the answer is so clear-cut? Well, of course there's always the traditional academic dilemma that professional journals don't publish papers if all they do is agree with what's already been written. No, you have to have new revelations and the best way for that is to say everyone before you was full of baloney. Writing papers or books with a new spin can lead to nice little perks like academic tenure which lands you a job for life provided you can put up with teaching American History 101 every other semester.

Book publishers, too, want the blockbuster. Don't publish a book about a guy who's been boozing so much that he finally croaks. No, find someone who will write that the guy was robbed or kidnapped, has a rare medical condition, or maybe that he was even the victim of a diabolical murder plot. Book publishers, it should be remembered, have considerable leeway in the content of a book. This is particularly true if it's about someone who's dead and particularly if it's about a famous historical figure. The way things are now you'll find tenured professors with endowed chairs publishing books that probably would have been rejected had it gone before a thesis committee. But a profit minded publisher can decide for themselves what they want to print.

And finally there's always that pesky minority of people who simply note there are inconsistencies and unanswered questions in the accounts of Moran, Snodgrass, and others. Could it be, they wonder, that there is more than meets the eye about Edgar's death? And so they begin to dig a little deeper.

Edgar's Beginnings

Edgar Allan Poe was born on January 19, 1809 in Boston. Both his parents, David and Elizabeth Poe, were actors. Strange as it seems with today's worship of media celebrities, at the time acting was quite a disreputable calling, and his father apparently abandoned the family not too long after Edgar was born. Elizabeth died in 1811 and according to Edgar, David died within a few weeks of Elizabeth. Through the arrangement of his grandfather (also named David and who had been a friend of George Washington and Lafayette), a tobacco merchant living in Richmond, John Allan and his wife Frances, agreed to raise the two-year old Edgar. Then to pursue his business interests, the Allans relocated to England and naturally they took Edgar with them. As was typical for middle and upper class British kids, Edgar was enrolled in a boarding school away from the Allans.

Early on Edgar showed a talent for writing. What really struck his teachers was that when assigned to write poems what came from Edgar's youthful pen was actually poetry not schoolboy doggerel. Likely it was his teachers' praise that got him thinking about a literary career.

Edgar wrote poetry.

Unfortunately Mr. Allan's business had not done as well as Edgar's schooling. He had never become rich and tobacco was not growing (no pun intended) in England. The tobacco business which he had run with his partner Charles Ellis was dissolved. He admitted to Charles that "we have erred through pride and ambition" adding that he hoped "we shall yet have an opportunity to conduct our business like sensible and reflecting men." Maybe, he added, he might become a farmer or planter.

But not in England. In June, 1820, Mr. Allan, Frances, and young Edgar sailed from Liverpool. After 36 days and a rough sea, the landed in New York and from there made it back to Richmond.

Well, with a failed business and little cash flow, the Allans ended up living in various houses in Richmond. Edgar continued his studies at the school run by Joseph Clarke, a hard-nosed but able classical scholar who also taught mathematics and the sciences of the time. Again as in England Edgar excelled at his schoolwork but didn't live at home.

Edgar continued to show his ability in writing poetry and had compiled a small book of poetry which one of his schoolmates remembered was mostly about the various Richmond lasses. Mr. Allan asked Joseph if he should have it published. But Joseph cautioned against it. Edgar, he said, was a bit too full of himself already and having a book published when he was only fifteen would give him a swelled head that could never be shrunk back to human proportions.

John kept trying to get back into business but that was hard to do without much capital. Then on March 25, 1825, William Galt, John's uncle and one of the richest men in Virginia, made his will and left John pretty much everything. This included three estates, all the attached property, and several hundred thousand dollars, equivalent in today's cash to tens of millions of dollars. And if that wasn't good enough news, the next day, William died.

Mr. Allan could now assume the life of a rich man. And he did. He bought a mansion in Richmond, and keeping with the English custom of giving their house a name, he dubbed his new residence "Modavia". And like many wealthy men who inherited their fortune, he also thought of himself as a self-made man who had pulled himself up by his own bootstraps. And fortified with his new assets he got back into business.

And Edgar? Well, he was now the son of a rich man. Best of all, he had a clear cut path to being a poet. After all, if Lord Byron could become a poet by living off his inherited wealth, then why not young Edgar Allan? But of course it would beef up his literary credentials to have a college degree (Lord Byron went to Cambridge). So in 1826, at the age of seventeen, Edgar went off to the University of Virginia.

Edgar the Cavalier

Although it had been founded by Thomas Jefferson in 1819, by the time 1826 rolled around, the University of Virginia at Charlottesville really had only been in practical operation for about a year. Tom decided that the U of V would be a different type of university where students could learn largely on their own. They had two - count 'em, two - hours of classes each day and the formal sessions ended around 9 o'clock in the morning (yes, that's in the morning). The rest of the time, Tom felt, they could spend in private study, philosophical discourse, and scholarly debate.

But somewhere, somehow, Tom had forgotten these were college kids. After about a year all his ideas of student autonomy, self-study, and internally regulated discipline had been pretty much been shot. Fights, duels, and even riots had broken out. Edgar's letters to Mr. Allan detailed times of almost sheer pandemonium.

The violence was largely fueled by the Three Big D's: Drinking, Damsels, and Dough. Trips to the taverns and the sporting establishments raised both spirits and hormones. Gambling was a favorite pastime. Card games, although they were forbidden by the college rules, were actually organized and booked by the staff who managed the dormitory dining rooms.

Trouble at the U of V: Drinking, Damsels, and Dough

Edgar joined in college life with much élan. Although he didn't (we don't think) participate in fisticuffs, knifings, or duels, it was here he began his life-long bout with the bottle. But it was money that really did Edgar in.

The exact nature of Edgar's financial woes are not really clear cut. Gambling is the logical (and traditional) explanation. Some writers say Edgar ended up owing over $2000 - big money in the early nineteenth century. Edgar admitted he did gamble, and in a recurring theme, said his companions had led him astray. But he also said he never would have wandered afar if only Mr. Allan had sent him more money.

After a year at school Edgar owed more money than he could pay off, and his university career came to a screeching halt. He worked briefly as a clerk for Mr. Allan's business but it seems he spent more time scribbling poetry on the blank ledger sheets than adding up sales. Soon and realizing that living with Mr. Allan had lost its charm, Edgar moved out.

Edgar Perry, PFC

Although Edgar had done well at the university, his chief skills were foreign languages (mainly French) and writing poetry. Not quite knowing how to put these abilities to use, he wandered up to Boston. Tradition has him trying his hand at acting, but even if this is true, he didn't get very far trodding the boards.

With no other prospects for education and no job, the seventeen year old Edgar Allan Poe signed up in the US Army as the twenty-two year old Edgar A. Perry. He stayed in Boston for a while, and in October, 1827 shipped out to South Carolina for a year.

Private Edgar A. Perry

Oddly enough, Edgar did pretty well in the army, probably because he really didn't have much to do. Certainly he had enough time to publish his first book of poems. This was "Tamerlane and Other Poems", and shortly afterwards he put together a second book, "Al-Araaf, Tamerlane, and Minor Poems". According to the second deal (and possibly the first) Edgar would have to make up the difference if the books didn't cover the costs. Figuring after almost two years, Mr. Allan would have cooled down, he wrote and asked his foster father to stand as surety.

The letter no doubt came as a surprise since Mr. Allan had no idea where Edgar was. As befitting a future fiction writer, Edgar could be pretty liberal with the truth. In fact, some of his friends had been receiving his letters marked "St. Petersburg, Russia", and Mr. Allan himself had been telling people he figured Edgar had gone to sea. But after receiving the letter, Mr. Allan agreed to cover the costs. He did so rather grudgingly, though, telling Edgar that "Men of genius do not need my aid." Edgar wrote back thanking Mr. Allan, but he didn't appreciate the snooty remark.

Edgar at West Point

At some point in his military career, Edgar decided he wanted to be an officer. No doubt he saw the officers as people who walked around, told the soldiers what to do, and sat on their rear ends. So if Edgar could publish two volumes of poetry as enlisted man, then as an officer he ought to be able write several anthologies. Also officers had better food, lived in better quarters, and even got a whiskey ration. All in all they had a better deal.

There were two ways to become an officer. You could rise through the ranks - which would take about twenty years - or get into the United States Military Academy at West Point, which would cut the time to four. The main trouble was Edgar had signed up in the army for a five year hitch and he'd only served two. So to get in he had to first to get out, so to speak.

Fortunately at the time the army provided a nice little loophole. Enlisted men could get out anytime they wanted - provided they found a substitute. Naturally the substitute expected something extra, and the substituteé had to pay the substitor a bit of up front money.

The Substitute System: A nice little loophole

Once more Edgar wrote to Mr. Allan, who probably wasn't too pleased to get another letter from Edgar asking for more of his capital assets. But, Edgar had hastened to add, the substitute would only cost $12. Unfortunately it was really $75, but Mr. Allan didn't learn about that until later.

Mr. Allan, to his credit, did write John Eaton, the US Secretary of War, asking that Edgar be appointed to West Point. Although Mr. Allan's letter was a bit strange (mentioning Edgar's gambling at Virginia), Edgar also had good referrals from his superior officers. On June 30, 1830 Edgar took the entrance exam and Cadet Edgar Alan Poe began his studies at West Point.

And almost immediately Edgar wanted out. Far from having the two hours a day regimen he had found at Charlottesville, Edgar was now having to rise at sunrise and go to classes from 6:30 in the morning until 9:30 at night (yes, at night). Taps was at 10:00, leaving Edgar little time for writing poetry.

In principle, getting out was pretty easy. He could just resign. The only kicker was he needed parental approval.

Normally Mr. Allan would have fumed and ranted about his feckless foster son with the short attention span, but still would probably have gone ahead and given the required permission. But at the same time Mr. Allan had received a letter from Sgt. Samuel "Bully" Graves, who was Edgar's substitute. Where, Bully asked Mr. Allan, was his $75?

Bully had already written Edgar about the money. Edgar in turn had written back but sent no payment. So he could bolster his position when he wrote to Mr. Allan, Bully decided to enclose Edgar's letter with his own. In the letter Edgar told Bully that he had already asked Mr. Allan a dozen times to forward Bully the money. But as Edgar put it, Mr. Allan kept shuffling him off.

Edgar clearly felt Bully deserved some further explanation for Mr. Allan's neglectfulness. The problem, he had written, was "Mr. A. is not very often sober."

Sober or not, often or not, Mr. A. almost had a cow. We don't have his letter to Edgar but it must have been a doozy. But we can be certain that he told Edgar that this was the end, he never wanted to hear from Edgar, and that he, Mr. Allan, would never write to Edgar again. That, at least implicitly, meant there would be no permission for Edgar to resign from West Point.

We do have Edgar's letter back to Mr. Allan and we know it's a doozy. In a spittle flinging epistolary tirade, he trashed Mr. Allan generally, berated Mr. Allan's stinginess, and added in what must have been a futile attempt to make Mr. Allan feel guilty, that he, Edgar, probably wouldn't live much longer. As far as him saying Mr. Allan was not often sober, Edgar added, well, Mr. Allan knew the answer to that.

Besides, he said, he didn't need Mr. Allan's permission to resign. He could leave West Point anytime he wanted. So there.

Which is what he did. Edgar quit attending classes, going to drill, and refused to follow orders. He even stopped going to church. Within a month he was called before a court martial for neglect of duty and disobedience to orders. He was found guilty, and on March 6, 1831, Edgar Allan Poe was dismissed from the service.

In Baltimore

The problem was where to go. Mr. Allan wasn't going to have anything to do with him, so Richmond was out of the question.

There was Baltimore, though. His grandmother Elizabeth (David Poe's wife) was living there on her husband's Revolutionary War pension. With her was her daughter, the widowed Maria Clemm (Edgar's aunt), and Mrs. Clemm's daughter, Virginia (his cousin) who was called Sissy.

Edgar's older brother, William Henry, had also been living with Mrs. Poe and Mrs. Clemm for a number of years. Only in his mid-twenties Henry was quite a prolific poet and was regularly published in the local magazines and newspapers. Whether he got paid for his poems isn't known, but if he was it probably wasn't much. What is pretty certain is Henry used more of the household income than he took in since Henry had developed a major problem with the bottle. Within a year of Edgar's arrival, Henry died.

The Baltimore Household: Mrs. Poe, Mrs. Clemm, Virginia, and Henry

Edgar's own contributions to the household also must have been meager. At first, probably everyone lived off Mrs. Poe's pension. It was only $240 a year which wasn't much, but in an era where $500 was a respectable income, it was enough to get by.

Edgar, though, did make some money by the one sure method he knew outside of gambling - borrowing. He ended up being $80 in debt which was a lot of money in 1831. What was worse, at that time unpaid bills could land the insolvent in the hoosegow and there was a distinct possibility Edgar would go to jail. So he did the only thing he knew to do when his finances got desperate. He wrote to Mr. Allan and asked for the money.

Mr. Allan is often looked on as a stingy, ungrateful tightwad who looked on his foster son as nothing more than a pecuniary irritant. Whether this is a fair picture of the man's character or not, for now Mr. Allan arranged for a friend to pay off Edgar's debt and bail him out if he was in jail (he wasn't). He even sent Edgar a little extra for himself.

Three years later, in 1834, Mr. Allan died. The story that Edgar went to Richmond for a last visit and Mr. Allan drove him from the room with his cane is not credited by all historians. But it's also true by that time Mr. Allan had (literally) written Edgar off. In his will Mr. Allan provided for three children from his second marriage and any kids he produced by fooling around. But Edgar was cut out entirely.

In later years Edgar was surprisingly generous to the memory of his foster father and wrote that the difficulties between the two men were at least in part his own fault. And given that Edgar's last letter to Mr. Allan was still one more plea for money, it's not hard to sympathize with Mr. Allan a bit. Just a little bit.

Edgar Makes Some Money

All along Edgar had really wanted to be a poet and in fact had made not too bad a start at it. With two volumes of poetry under his belt, after coming to Baltimore he published a third volume of poems. This last book, titled simply "Poems", was published in 1831 and was paid for at least in part by subscriptions from some of his West Point classmates. So at twenty-two he had more to show than many other nineteenth century American authors - Hawthorne, Longfellow, and Irving - had achieved at the same age.

On the other hand, he certainly hadn't made any money as a poet. Instead short stories and novels (often serialized) had more potential to bring in at least some income, and it was in Baltimore that Edgar began writing prose. Unlike today, most magazines and newspapers existed by subscription sales and newsstand purchases rather than by plastering advertisements throughout the issue in such prolificacy as to make the magazine unreadable. So editors and publishers continually tried to find ways that would attract new subscribers. Even daily newspapers printed short stories.

In Baltimore Edgar began writing short stories.

In an effort to keep fresh stories coming, publications would hold writing contests. Edgar seems to have submitted entries regularly. Even if a story didn't win, the papers would sometimes publish it if the judges thought it had merit. Edgar's first published short stories were non-winning entries in these types of contests.

Edgar's big break came in 1833 when the Baltimore Saturday Visiter (that's the way they spelled it) held a contest for the best poem and best short story. Edgar submitted six stories and one poem, and the winners were announced October 12. Although Edgar's poem didn't win, his short story "MS Found in a Bottle" took the first prize, $50.

Edgar the Editor

After "MS Found in a Bottle" appeared, Baltimore's intelligentsia began looking on Edgar as a serious writer. Baltimore publisher Joseph P. Kennedy in particular was impressed with Edgar and became one of his lifelong friends and mentors. Edgar's writing also brought him to the attention of editors from other cities. In 1835 Thomas Willis White, the editor of the Southern Literary Messenger in Richmond, agreed to published Edgar's story "Bernice". At the same time, White had started looking for an assistant editor, and probably at the suggestion of Kennedy, he chose Edgar.

Edgar's job on the Messenger marked three milestones. For one thing, it was his first editorial job on a magazine staff. Secondly, it entailed a move back to Richmond. And finally, it gives us the first positive evidence that Edgar had a real problem with booze.

Edgar had taken up his post in Richmond by August 1835. The plan was for Mrs. Clemm and Virginia to join him later. But after working at the Messenger maybe a month, he was off the staff and back in Baltimore.

Attending to business

Shortly afterwards - on September 29, 1835 to be exact - Mr. White sent Edgar a kind and fatherly but nevertheless stern warning about the dangers of a man "who drinks before breakfast" adding "no man can do so, and attend to business properly." He did leave the door open for Edgar's return, but added the deal was off the moment Edgar hit the sauce.

Today some fans of Edgar maintain his drinking was a not steady chronic problem but was composed of short periodic binges. They point out that Edgar could often go long periods without touching a drop. True, many of the stories of Edgar's' intemperance are from Edgar's enemies, but we hear the same thing from his friends. Assertions of Edgar's abstinence - that he hadn't touched a drop in months - often came from Edgar himself and again are as often contradicted by people who showed up at his house or office and found him plastered.

Edgar and Virginia

Fortunately Edgar did go back to work for Mr. White. Then almost immediately Mrs. Clemm wrote Edgar that Neilson, his Baltimore cousin, was wanting to provide for Virginia's education. We don't know exactly what Mrs. Clemm wrote but it looks like the plan would be that she and Virginia would stay in Baltimore, and they would move in with Neilsen. Edgar was devastated since he and Virginia had already planned to get married.

In her letter, Mrs. Clemm was, strictly speaking, asking Edgar's advice, not saying that's what they intended to do. So when Edgar responded in a letter that was a true cri de coeur everything got back on track. On June 30, 1836 Edgar and Virginia were married in Richmond.

Edgar's marriage continues to raise eyebrows even today - or perhaps we should say particularly today. Marriages between cousins are odd in our time (and in most states first cousin nuptials are illegal), but they were pretty common back then. But the real brow twitcher is their age difference. When they got married, Edgar was twenty-seven. Now you might find some who write that Edgar married Virginia when she was only twelve. That, of course, would be absurd. Edgar would never do anything like that. He married Virginia when she was only thirteen.

Even making allowances for this being ante-bellum America, thirteen was still pretty young for a girl to get hitched. And as legal and consensual as the marriage was, Edgar and Mrs. Clemm were well aware of the possibility of social censure from the union. So Edgar convinced the minister that Virginia was a "full twenty-one years" of age, something that must have been hard to do if the man had normal eyesight.

Edgar convinced the minister Virginia was a "full twenty-one years of age".

A Couple of Years in Richmond

In his tenure at the Messenger Edgar really proved his mettle. He wrote articles, short stories, and reviews and the Messenger was soon a hot literary item. By one account (mostly Edgar's) the readership leapt from about 500 to over 3500 in a year - pretty good in an era where a good chunk of the population couldn't even read. Historians agree it was Edgar who did it but not all agree the readership up went by a factor of seven.

His pay, though, was rotten - $104 a year. Even in those days that was starvation wages. Probably Mr. White kept the wages down by pointing out that Edgar could always make more money writing stories and stuff for other publications. There's some truth to this since he paid Edgar $3 a page to serialize his first (and only) novel The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket Comprising the Details of a Mutiny and Atrocious Butchery on Board the American Brig, Grampus, on Her Way to the South Seas in the Month of June, 1827, with an Account of the Recapture of the Vessel by the Survivers [sic]; Their Shipwreck and Subsequent Horrible Sufferings From Famine; Their Deliverance by Means of the British Schooner Jane Guy; the Brief Cruise of This Latter Vessel in the Antarctic Ocean; Her Capture, and the Massacre of Her Crew Among a Group of Islands in the Eighty-fourth Parallel of Southern Latitude Together With the Incredible Adventures and Discoveries Still Farther South to Which That Distressing Calamity Gave Rise. After reading the title most people probably decided they didn't need to read the book.

Edgar's pay was rotten.

Even when Edgar cut out his drinking, all was not well between the two men. Yes, Mr. White paid Edgar $3 a page for the novel, but he figured that it cost $20 a page to print. So by January, 1837, Thomas was pretty much fed up with his cantankerous employee and he wrote to his friend Nathaniel Tucker (whose friends called him Beverley) to express his disgruntlement.

Poe pesters me no little. He is trying every maneuver to foist himself on someone at the North, at least I believe so. He is continually after me for money. I am as sick of his writings as I am of him and am rather more than half inclined to send him up another dozen dollars in the morning and along with it all his unpublished manuscripts.

And that's pretty much what happened. Nevertheless, the job at the Messenger, as short as it was, was the beginning of the real literary career of Edgar Allan Poe. But moving on was equally as important, and in February 1837, he, Virginia, and Maria left Richmond and moved to New York expecting it would be relatively easy for Edgar to find work. However, no permanent editorial job materialized and he had to support himself by freelancing. That wasn't the life he wanted, and in the summer of 1838, he, Virginia, and Mrs. Clemm moved to Philadelphia.

Edgar In The Town That Snowballed Santa Claus

In colonial days, Philadelphia was THE city in America. Unfortunately almost as soon as Independence was declared, the City of Brotherly Love began its long and torturous slide out of prominence. The flow of immigrants (which ultimately made America into the world's sole superpower) was siphoned off into New York, and at the same time the political life of America moved south to what was originally called the "Federal City". So in less than two hundred years Philadelphia went from being the center of American culture, learning, art, and government to end up as the Town That Snowballed Santa Claus.

Edgar comes to Philadelphia

For Edgar, in any case, Philadelphia was the right place at the right time. When he arrived, a noted comedian and actor, William E. Burton, decided to shift his efforts from acting to publishing. His magazine, Burton's Gentleman's Magazine, had been coming off the presses for about a year. Edgar wrote William and offered his services as editor.

Although acting was moving up a bit in the standing of polite society, men like Burton certainly didn't help the fancy's reputation. In 1834 he had skinned out of England because he married a sixteen year old orphan. Although that doesn't seem too bad - after all, Edgar married Virginia when she was thirteen - William already had another wife and kid. This tendency to marry women without legally ditching the previous lot was a pretty steady characteristic of William, and eventually he may have had as many as three wives at one time.

It wasn't until May 1839 that William got back to Edgar. Compared to the Messenger, the proposed pay seemed reasonable. William would pay Edgar $10 a week, and he said that two hours a day would be all that was needed. Very good pay in 1839.

Once more Edgar jumped into being a magazine editor with gusto, and as in Richmond, he did quite well. He solicited established authors and poets (including Longfellow who said he was too busy) and occasionally provided an original story. It was at this time that he wrote the famous "Fall of the House of Usher" which is (somewhat lamentably) many kids' first introduction to Poe.

Despite his fairly liberal salary and the free time, Edgar still couldn't make ends meet. Then as now, if you wanted to live beyond your means you just went into debt. But since there were no credit cards with overinflated spending limits, you had to borrow from your friends. One of Edgar's borrowing friends was Burton.

After a year, William wrote Edgar and asked him to repay his accrued debt of $100. It was a testy letter and not only did William ask for his money, but he began ragging on Edgar that he was being slack on the job. Even though the magazine was now in financial difficulties, he said, he was still paying Edgar his $10 a week for a measly 2 to 3 pages of writing per issue. Clearly William didn't think he was getting his money's worth.

Edgar's reply was equally testy. First, he was giving William more than 11 pages per magazine, not 2 or 3 (Edgar was right on this point). On top of that he devoted a lot of hours to proofreading, corresponding with contributors, and doing the other day-to-day chores an editor needs to do while editing. But whatever William thought of his editorship, he only owed Burton $60, not $100. If William expected the higher amount, he could stuff it.

Burton soon started spreading rumors that his editor was tippling. As always Edgar denied the allegations, saying he had been strictly temperate except for a single lapse where he occasionally drank cider. The reference to the single lapse makes some authors believe Edgar was being honest - if he was dishonest he would have said he hadn't drunk anything. Others think he did protesteth a bit too much, and he had really had been hitting the bottle.

Burton said Poe was tippling

There is some independent corroboration that Edgar was dipping into the sauce. About a year after Poe died the publisher of the Gentleman's Magazine, Charles Alexander (essentially Burton's boss, but he also liked Edgar) wrote that Edgar's "problem" had been a common topic of conversation in Philly. Of course, at that late date it's possible that Alexander was including other episodes from the late 1840's, but its all the more likely that when Edgar was on the Gentleman's Magazine, people really were talking about his drinking. And the most logical explanation for why people would talk about Edgar's drinking is because Edgar really was drinking.

With friction building between him and Burton, it's no surprise that in June 1840, Edgar left the Gentleman's Magazine. But his plans were to stay in Philly and to start a magazine of his own. After all, if a non-literary ham like Burton could be a publisher, surely a tried and true poet and author like Edgar could do even better.

Try as he might, though, Edgar couldn't raise the capital. So once more he had to settle working for a magazine owned by someone else. Strangely enough, it happened to be Burton's old Gentleman's Magazine, now repackaged and renamed.

What had happened was Burton had tired of the magazine business. Either that or he found out that running the magazine without Edgar was a pain in the rear end. So about the time he split with Edgar, he sold out to George Graham, a twenty-seven year old Philadelphia lawyer. Since George was already publishing another magazine, and he simply merged the two. Calling a spade a spade, Graham named his new magazine Graham's Magazine and hired Edgar, first as a freelance contributor and then starting in April 1841 as an editor.

Edgar's pay was $800 a year. That could be considered a fair middle class wage. Supporting himself, Virginia, and Mrs. Clemm certainly should not have been too difficult in an era where a loaf of bread was perhaps a nickel and there was no income tax. But Edgar, like a lot of people, tended to live a bit beyond his means. Also at the time, if you were middle class or well-to-do, soiling your hands with money was a bit beneath your dignity, and financial transactions, great or small, were handled on credit. So before you knew it you could be owing more than you took in, and that was a never ending problem for Edgar.

It was also in Philadelphia that Virginia's health seriously began to fail. She had contracted what was almost certainly tuberculosis and in January 1842 as she was singing and playing the piano she began to cough up blood. Only twenty years old, she was bedridden for months. Although her condition did improve, she was never really very well after that.

Blowing It in Washington

Edgar's real dream was still to own his own magazine. He figured he'd never do that if he was stuck with a job as a lousy staff editor. That may be the reason in August 1842 he left Graham's Magazine. Certainly his relationship with George was much better than it was with Burton, and in the final issue Edgar edited, George wrote a short note wishing Edgar all good luck.

Edgar's replacement on Graham's was Rufus Griswold. Although officially the men had a cordial relationship, in reality they didn't like each other all that much. Rufus was something of a grump to begin with, and Edgar didn't help things when Rufus asked Edgar to write a review. Edgar knew that Rufus wanted him to puff up the book and (perhaps perversely) wrote a decidedly negative review. Then (almost certainly perversely) Edgar hand delivered the article, knowing Rufus wouldn't have time to read it before handing over the fee. Edgar no doubt thought he had put one over on his successor but his fun with Rufus would come back to haunt him or at least to haunt his reputation.

After he left Graham's, Edgar once more began to seriously look for ways to launch his own magazine. At first he proposed to call it Penn but thought that was too regional and settled on the The Stylus. One of his potential partners was Thomas Clarke, who at the time published another magazine and seemed willing to put up half the funds for another if Edgar could dredge up the rest. So Edgar decided to go to Washington and canvas out the rich and powerful. As long as he was there he figured he could also check up on the possibility of a government job.

That Edgar, a writer, was looking for non-literary employment in general and a government job in particular wasn't unusual. At this time no American author, that's no American author, made their real living by writing fiction or poetry. Longfellow was a professor at Harvard (making over $2000 a year) and Washington Irving, who had written the "Legend of Sleepy Hollow" and "Rip Van Winkle", was a diplomat to various European countries. Nathaniel Hawthorne himself had landed a job at the Boston Customs House, and Edgar figured he ought to be able to get a job like that in Philly.

Mr. Poe goes to Washington

Now to get a government post, you first have to get appointed. The best way for that was to go to Washington and in the presence of an "influential friend", call on one of the bigwigs. The bigwig would then go to a biggerwig and on up the line until they found the biggestwig who had the power to give you employment. This was, after all, the time before civil service exams and if you were among Washington's elite, landing your friends and neighbors a government job was almost considered a constitutional right. For those who don't know it, even today personnel on the staff of federally elected officials are not, repeat not, subject to civil service requirements.

Armed with a letter of introduction, Edgar decided to call on Richard Tyler, who was the son of President John Tyler, who obviously had been padding his own payroll. Exactly what happened between the time Edgar left for Washington and returned back home to Philly isn't clear to modern readers and it probably wasn't all that clear to Edgar either. Evidently he called at the home of one of his friends and started drinking and didn't stop. All in all he made a complete fool of himself for the rest of his stay. At one point an acquaintance said he once saw Edgar during the day and he was "pretty steady", implying that even at that time, he wasn't totally steady. Even before Edgar left Washington word got back to Clarke that his potential partner was reeling around town being loud-mouthed and obnoxious to his various Capitol City hosts and hostesses. Eventually Edgar found his way back home. Not surprisingly, no government job or any new backers for the magazine had materialized.

Among Edgar's faults was a tendency to blame others for his own lapses, which means he was pretty much like everyone else. His excuse here was his hosts cajoled him into drinking port wine and mint juleps which were washed-down with rum-laced coffee. Admittedly at that time Washington's culture was largely Southern, and with it came the hale-fellow-well-met conviviality so easily lubricated by liquor. But it's also true a lot of people weathered Southern hospitality without slobbering all over their hosts' carpets. To his credit, Edgar eventually realized what had happened really was his fault, and he wrote letters to everyone and tried to patch things up and not to tell people he had worn his coat inside out. But he still didn't land a job and had pretty much blown his chance of getting backers for his magazine.

Edgar in the Big Apple

After Edgar quit Graham's, he continued doing free lance work and writing stories. Even after his debacle in Washington, he still thought he had a chance for the job at the Philadelphia Customs House. At one point he even thought he had the job sewn up, but he didn't.

After two years of 1) failing to get a government job, 2) failing to start his own magazine, and 3) failing to make steady work freelancing, Edgar thought it best to once more pull up stakes. So he and Virginia hopped a train to the Jersey shore and from there took a steamboat to New York. Edgar asked Mrs. Clemm to stay behind for a bit and sell the items they wouldn't have room for in their new home. Mrs. Clemm did what she asked and more. In fact she sold at least one rare book that wasn't even Edgar's, and the owner ended up having to track it down and buy it back.

On April 7 1844, Edgar and Virginia arrived in New York. Except for when Edgar tore his pants, the trip was pretty uneventful. They found rooms in a boarding house (whose food Edgar praised most effusively) and he began looking for work. No doubt at first he did more freelance writing and he may have been briefly on the staff of the Sunday Times. In October we know he was working on the New York Evening Mirror whose owners found him both punctual and reliable.

The trip to was uneventful.

Whatever Edgar's function was on either the Times or the Mirror, it did not give him the freedom or authority he wanted. But in February 1845 Charles Briggs, editor-in-chief of the Broadway Journal offered him a job. Edgar's name appeared on the masthead as editor along with Briggs, and the job was pretty much as before - get new authors, perform routine editorial duties, and write some stories of his own. The main problem was the Journal was on shaky financial footing which eventually (but briefly) worked in Edgar's favor.

Writing "The Raven" and Screwing up Again

While at the Journal Edgar wrote a number of his better known stories. These included "Descent into the Maelstrom", "Liegia", "The Masque of the Red Death", and "The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar". But by far most of his writings were reviews, and it was on the Journal that he garnered a serious reputation as a literary critic. In fact during his lifetime that's the way most other writers looked on him.

It was when writing criticism that Edgar's more ornery side kept showing up. Edgar's reviews continued to be savage and at times Edgar could become almost monomaniacal about a topic. Perhaps this tendency is best illustrated when he accused the by-now famous poet, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, of plagiarism.

Poe accused Longfellow of plagiarism.

The dictionary definition of plagiarism is "to commit literary theft, present as new and original an idea or product derived from an existing source" (this is from Merriam-Webster's dictionary and the quotes are to show it isn't being plagiarized). The problem with this definition is it's pretty vague, particularly as to what "idea" and "derived" actually mean.

Authors and artists are always influenced by the works of others. In that sense virtually all artistic creations are "derived" from another. Shakespeare freely borrowed plots from other sources, but most scholars don't consider Shakespeare to be a plagiarist. Even today you might find specific plot points in one book that are clearly borrowed from another. However taking the same words and phrases from a work is a no-no.

A sticky point is neither plagiarism nor its legal twin copyright infringement has to be intentional. Things are even stickier for composers who have to be careful that a theme that pops into their head wasn't something they heard years ago. Even if the similarity is purely coincidental, the composer would still be liable as former Beatle George Harrison found out when the copyright owners of "He's So Fine" claimed he was using their melody for his hit song, "My Sweet Lord". Even though the judge said he didn't think George had intentionally snitched the tune, George had to pay up.

As it was, Edgar said Longfellow's poem, "Midnight Mass for the Dying Year" was plagiarized from Tennyson's "The Death of the Old Year". Although the themes of the two poems are similar, "waning year" poetry was being written at least back to the Middle Ages. So Edgar really seemed to be stretching it. In later articles, Edgar kept hammering at Longfellow so much that Edgar's former boss, George Graham wrote Longfellow saying he didn't know what was the matter with Edgar. For his own part Longfellow seemed indifferent to the brouhaha and pretty much ignored Edgar.

Edgar had in fact set himself up. About the time he was trashing Longfellow he himself had published a poem that is now one of, if not the most famous poem in American literature. This was "The Raven". Probably written during his tenure at the Mirror, it was first printed there in January 1845.

Almost from the start the poem was a hit. People read the poem, recited it, and even parodied it. The latter continues to this day and the poem had the singular honor of appearing - verbatim and illustrated in comic book format - in MAD Magazine. Perhaps the greatest honor for the poem - or indignity depending on how you think of it - was in 1999 when the name was slapped on the Cleveland Browns when they moved to Baltimore.

With Edgar having produced a hit, Longfellow's champions didn't waste any time. Almost before the ink was dry, they were pointing out that in "The Raven" there was a reference to a "purple curtain" just like there was in "Lady Geraldine's Courtship" by Elizabeth Barrett (soon to be Elizabeth Barrett Browning). Elizabeth had also used the word "Evermore" (and even "Ever, evermore") in a manner that seemed awfully close how Edgar used "Nevermore". Clearly, the critics implied, such phrasing of the verses were similar enough so that if you thought Longfellow plagiarized Tennyson then you really had to say Edgar plagiarized Elizabeth.

Edgar really had no answer for all this, particularly since he knew Elizabeth's poetry well and had even reviewed it. For now about all he could do was write spluttering and spittle flinging tirades that began to make even his friends wonder if Edgar was going off the deep end. Even his boss, Charles Briggs, didn't quite know what to do.

Was alcohol involved in this literary lambasting? It's impossible to say but about the time Edgar was trashing Longfellow, his drinking once more began to get out of hand to the point it ended up costing him a real ally.

In 1841, James Russell Lowell, a young poet and lawyer had founded the literary magazine The Pioneer. Ten years Edgar's junior, James soon became both an admirer of and a mentor to Edgar. James not only published a number of Poe's stories, but he also wrote the first (and short) biography of Edgar.

Despite a relatively long corresponding friendship, the two men met only once at Edgar's home in New York. It was probably around May 1845 although Lowell placed the visit two years earlier. But whenever it did happen, Edgar appeared "soggy with drink" according to James's (polite) recollection. But it seems Edgar may have even made himself a bit obnoxious. Certainly Lowell's later comments weren't all that favorable and in his most famous quote about Poe, Lowell wrote Edgar was "three fifths genius and two fifths fudge". And that was one of the nicer things Lowell said.

Even a decade later Mrs. Clemm (who was present) still felt bad about the visit. Six months after Edgar died Mrs. Clemm, who was now in bad financial straits, asked Lowell if he could find a buyer for some copies of Edgar's works that had recently been published and that Longfellow (!) had given her some money for some volumes. In her letter she asked that he forget the unhappy episode at her house since Edgar was in a state that "he didn't know what he was saying." Although the language is elliptical (as it usually is when Edgar's friends and family talked about his drinking) it's clear Edgar was potted when Lowell showed up and James left with less than charitable feelings. For what it's worth, James did help Mrs. Clemm out.

Owner of the Journal and Blowing It in Boston

Edgar never gave up on wanting to have his own magazine and toward the end of 1845 he - technically and temporarily - achieved his goal. Even when Edgar first joined the staff, the Journal was on pretty shaky grounds. Soon the other editors started jumping ship and by the summer Edgar was the only editor left on the masthead. It came about by attrition, but by October Edgar Allan Poe was "sole editor and proprietor" of the Broadway Journal. Edgar had his own magazine at last.

But it meant nothing. To try to keep the magazine afloat he had to scratch for borrowed cash. His correspondence at this time is replete with letters to his friends begging for fifty dollars here and fifty dollars there. All in all it sounded like a repeat of his correspondence with letters to Mr. Allan. And it certainly didn't help the magazine that by that time he had completely alienated the whole city of Boston.

Not long before Edgar became proprietor of the Journal - the previous May, in fact - James Russell Lowell (never a vindictive man) had arranged for Edgar to give a lecture up in Boston. The idea was Edgar would talk about literature and read a new poem. But Edgar later claimed he couldn't write poetry to order. Instead decided to sneak in a renamed "Al-Araaf" which even back then didn't make sense to anybody. Since it's hard to read even the first verse without falling asleep and the poem's too long in any case, it's not surprising that people in the audience began drifting out before Edgar was finished.

After the lecture (and perhaps before) Edgar began drinking and at the reception afterwards began to trash the Bostonians. Word got out about Edgar's voiced opinions and Bostonian editorials came out trashing Edgar. Naturally Edgar responded in kind and published an article where he said he had deliberately pawned off "Al-Araaf" on the town of the Brahmins to show how dumb they really were. Why else, he said, would they praise a childish poem he had written in his early teens?

Of course, the Bostonians hadn't praise "Al-Araaf" (many had walked out) and he had written one of the most ridiculous American poems when he was about twenty. The Bostonians were miffed and Edgar now was pretty much persona non grata in his place of birth.

With most of Boston not going to renew any subscriptions, Edgar hooked up to Thomas Lane, another New York publisher. They decided to go halves. But it was too late. By January 3, 1846 the Journal went belly up. His performance at Boston wasn't the only reason he couldn't draw enough readers and backers to shore up the foundering magazine. But it sure didn't help.

Although Thomas had been only a partner for a few weeks, now Edgar had someone to blame. He later dismissed Lane as the man who presided over the death of the Broadway Journal. That may have been true, but Edgar was the man who helped steer it over the cliff. Or at least he couldn't stop its plunge.

The crush of the city had also gotten a bit much and probably thinking of Virginia, Edgar, had earlier moved everyone next to St. John's College (now Fordham University) in the Bronx. Edgar kept writing stories, reviews, and criticism, and he found the Jesuits at Fordham to be a surprisingly convivial bunch of fellows. The priests were, in fact, scholars and intellectuals who preferred to discuss history, science, and art rather than boring topics like religion. So every Sunday Edgar would take time off and spend a few hours with the priests, discussing literature, playing cards, and if we believe what others say, drinking.

The Final Years

Virginia's health had been steadily declining. Although at times she might seem sound enough, her "bronchitis" (as Mrs. Clemm called it) got worse and she was more and more confined to her bed. Finally, on January 30, 1847 she died. Say what you like about Edgar, he absolutely adored Virginia, and notwithstanding his drinking and money problems, any household where the mother-in-law practically worshipped her daughter's husband had to have been one of the happiest in America.

What surprised people was how well Edgar rebounded. Visitors reported Edgar was in good spirits and in excellent physical condition. He was deliberately getting exercise and he may have stopped drinking altogether. Soon it seemed he was seriously looking for a new Mrs. Poe.

It's hard to tell much about Edgar's relationship was with the fairer sex. He seems to have been popular enough with the ladies, many of whom commented on his good looks and gentlemanly manner. After Virginia's death (and even before) there had been whisperings that Edgar was something of a ne'er-do-well and that he was fooling around with other men's wives. That's possible, as it is for any human male with the normal set of organs which operate independently of the brain, but there is no real evidence for it.

It is indisputable, though, that Edgar developed at least what are called "literary courtships". Edgar appreciated the ability of many of the women poets he met and once "The Raven" became a hit, his reputation as a poet had eclipsed that as the cantankerous critic. Since at the time poetry was particularly popular with the ladies, it was natural that many of Edgar's admirers were women.

Frances Osgood, known as Fanny, had begun publishing poems at the age of fourteen. Her husband, Samuel, was a well known portrait painter and in reality he was the ne'er-do-well. She met Poe in 1845 shortly after "The Raven" was published. Fanny began writing Edgar and he wrote back, praising her own poems. By that time she and Samuel were separated, and rumors began to circulate that Fanny and Edgar were hitting it off. To quell such rumors they let things cool off, but they remained friends if a bit more distantly than before.

It was Fanny that arranged a lecture trip for Edgar in 1848 at Lowell, Massachusetts. While there Edgar met Nancy Richmond, known by the nickname "Annie". Edgar visited Lowell at least three times and Annie also went to Fordham at least once. Edgar wrote his poem "To Annie" and years later she legally changed her name to match the poem. Edgar's letters also prove conclusively that he and Annie had an interest in each other that went beyond well-rhymed couplets. The trouble was Annie was already married. Leaving a well-to-do husband and an officially stable marriage for an intermittently employed poet really wasn't a nineteenth century option. So nothing ever came of the relationship. Or at least nothing we know of.

Since it wasn't likely a relationship with Annie was going forwards, Edgar began paying attention to Sarah Helen Whitman, who at the time had been a widow for 15 years. Like Fanny, Helen as she was called, had been writing articles and poetry since she was a young woman and had garnered a respectable reputation. Helen had written to Edgar in 1848 with a poem and he responded with his own verse, "To Helen", which is not to be confused with an earlier poem of the same name, also by Edgar.

Helen and Edgar actually became engaged and almost immediately became unengaged. Here alcohol was indisputably the cause.

That Edgar was a real boozer is sometimes debated, but that Edgar had a reputation as a boozer isn't. So Helen said they couldn't get married unless Edgar stopped drinking completely. Edgar agreed.

Then a day or so before the marriage Edgar broke his pledge and someone ratted on him. Supposedly there was a stormy scene at Helen's house where she taxed her irresponsible fiancée with his perfidy. The story got out that after committing some ill-defined "outrage", Edgar was booted from the Whitman home.

In later years Helen denied there was ever a "scene" at her home where Edgar committed any "outrage". That there was a scene, however, is verified by the last letter Edgar wrote to her. The letter is a bit stiff with him addressing Helen as "Madam", and signing it "E. A. Poe". Normally his salutation was "Dearest Helen", and he closed with a simple "Eddy".

It was a typical irate Edgar letter. He did no wrong, he said, and Helen could check with two clergymen who would vouch for his honesty. How two ministers could verify Edgar didn't sneak a snort is a bit hard to understand, but then Edgar turned right around and said he did "lament" his own weakness. For that he accepted full responsibility. But he would not, he said, blame her for her own weakness. Helen, it turns out, was a snuffer.

The truth is there had been one heck of a scene. What happened was Helen told Edgar that someone had slipped her a note that told her Edgar had been seen surreptitiously fortifying himself the previous day. She didn't name names, but she did say her correspondent was someone whose honesty could not be doubted. That initiated a shouting match between Edgar, Helen, and Helen's mom (who didn't like Edgar). Somewhere along the line Helen doused her handkerchief with ether (used at the time for "heart problems") and took a hefty snuff which she claimed knocked her out onto the parlor sofa.

It's a bit hard to credit Helen's account. Dosing a handkerchief with ether (a slow acting anesthetic) and just sticking your nose in for a second would not normally be enough to anesthetize someone to the point of stupor. Also she claimed she was virtually unconscious on the sofa and yet she remembered enough to repeat the verbatim conversations in the room a quarter of a century later. More likely than not Helen was putting on a bravura performance of the weak and delicate nineteenth century damsel and hoped that by falling back on a conveniently located sofa she would bring the whole mess to an end.

William Parbodie, a friend of Edgar's and Helen's, was also present. From what he wrote, it does look like Edgar had tipped back the bottle at least twice the day before. It may even have been William that blew the whistle on Edgar as some people think he really had his own interest in Helen. Maybe. But William liked both Edgar and Helen and if he was the one who ratted on Edgar, it's equally likely he felt honor bound to tell it like it was.

The whole episode with Helen kind of puts a damper on the claim that Edgar drank mostly when he was unhappy. On the contrary he seems to have tipped his head back even if things were going well, as his last trip to Richmond shows.

The Final Months

Edgar was persistent. He was going to have his own magazine come hell or high water. But as always he needed financial backing and also someone to help with the actual nitty gritty of printing and distribution.

In April 1849 Edgar got a letter from a young publisher named Edward Horton Norton Patterson (yes, his two middle names were Horton Norton). Running a newspaper in Oquawka, Illinois (about two hundred miles up the Mississippi from St. Louis), Edward suggested he and Edgar go into business. Edward would do the grunt work and Edgar would be the editor. Despite the prospect of having a business partner named Edward Horton Norton from Oquawka, Edgar agreed.

But before the plans could move ahead, the men needed money and subscribers. Edward said once they had 1000 people signed up, he could go ahead and run off the first issue. With Edgar's fame, the best way was a lecture tour. He could not only use the money from the fees to provide ready money for the venture but if he made a good impression then he'd get people in the audience to subscribe.

Edgar left New York in on June 29. The itinerary is a bit confused. According to the traditional account, he immediately got into trouble in Philadelphia where his behavior was so suspicious he was hauled down to the police station. Someone recognized him and the Philly cops let him go. Soon he found his way to his friend John Sartain, one of the country's premiere engravers and who later became a teacher at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine the Arts.

When Edgar showed up he was hallucinating. He told John how men sitting behind him on the train were talking about him and plotting his murder. If it hadn't been for his "acute sense of hearing", he wouldn't have found out. Not believing Edgar's story, John was alarmed enough to stay with him when Edgar wandered down to the Schuylkill River.

Edgar said the men were talking about him

While looking over the water, Edgar began to tell John of the time he spent in the jail for counterfeiting (which was doubly false) and how people were plotting his murder. He also related how when in jail he saw a luminous woman who spoke so softly that only again by his acute hearing did he understand what she said. John realized Edgar was clearly on the verge of a crack up and took him back to his home. Edgar slept on a sofa and John slept on some chairs, not wanting to leave Edgar by himself.

The next morning Edgar was better and acknowledged to John that he had been suffering from delusions. Edgar then left and went to visit George Lippard, a young journalist and writer. The problem was Edgar was short of cash and asked if George could lend him a few bucks. George was broke (he had just paid his rent) but sent word out to some of Edgar's friends (including Sartain) that Edgar needed money. With George's help Edgar raised enough cash to go on to Richmond.

There are some, though, who question the timing of John and George's story. Instead they think with the passing of years there had been two closely spaced visits. The first was when Edgar was heading south to Richmond and he had the run in with cops but nothing more. The second visit was on Edgar's return and that's when he was freaking out. Although it's risky to start shifting episodes in time, the clothes John described Edgar wearing did more or less gibe with what he was found wearing in Baltimore on October 3. In Richmond people remembered him in good shape and well dressed.

On the other hand, Edgar's letters to Mrs. Clemm in early to mid-July right after he left New York show he was unusually agitated and nearly off his rocker. He started worrying that Mrs. Clemm was dead and frantically wrote her to see if she was all right. So the behavior John and George report times well with what is documented before Edgar arrived in Richmond.

The most reasonable explanation is that Edgar was suffering from acute alcohol withdrawal complete with hallucinations and delusions. That was in fact Edgar's own diagnosis and in a letter written in Richmond on July 19, he told Mrs. Clemm he had come down for the first time with mania a potu, the nineteenth century name for the delirium tremens. As usual Edgar steadfastly claimed he had not touched a drop during the time he was "totally deranged". That may have been true since the DT's normally set in after you stop drinking.

Once he recovered Edgar probably would have been all right if he had kept away from the liquor. But from his own actions on the trip and the statements of others, he must have started up once he was on the lecture circuit.

The Final Weeks

Edgar's lectures in Richmond were well-received critically and for the most part were financially successful. Even in small towns like Norfolk the audiences were enthusiastic. He lectured in and around Richmond for two months and it looked like Edgar very would be able to get his 1000 subscribers needed to launch his magazine.

Naturally when Edgar got to Richmond he looked up some old friends, one of whom was Mrs. Sarah Elmira Royster Shelton. She had been Edgar's first serious girlfriend and in their teens they had wanted to get married. But Mr. and Mrs. Royster did not think that Edgar was an appropriate suitor for their daughter. So when Edgar went off to the University of Virginia, Elmira's parents engineered her marriage with a more well-to-do young swain. When Mr. Shelton died at the age of thirty-six, he left Mrs. Shelton a wealthy widow.

Edgar showed up at Elmira's house unannounced. Possibly being a bit flustered at seeing her old flame, now a famous author, she told him she was just on her way to church which she never missed and he should call later. He did and almost at once he said they should get married. She thought he was joking and laughed it off, but later said she'd think it over when she saw he was serious. Whether Elmira actually agreed to get married is a bit uncertain since in her later years she waffled around the subject. But before Edgar left Richmond he wrote to Mrs. Clemm that he would be getting married.

But Edgar's problems weren't over. At least twice during his stay he had "attacks" which resulted in the doctors telling Edgar that recurrences could be fatal. In typical Edgar fashion, he blamed others and said that if they wouldn't tempt him, he wouldn't fall. Edgar took these warnings seriously and while still in Richmond, he went so far as to join the Sons of Temperance. We also can't rule out that Elmira, like Helen before her, made it a dictum that if they were going to get married, Edgar had to lay off the booze - permanently.

The trouble, though, is when an alcoholic has reached the state where he can go into the DT's, if the drinking isn't good for him then the stopping can be even worse. He can get caught in a start-stop cycle, either phase of which can be dangerous and life threatening. When Edgar left Mrs. Shelton for the James River Wharf to catch the steamboat to Baltimore, she noted he had a fever. Although this might have been due to a viral or bacterial infection, this is also a symptom of onset of the DT's. On the way to the boat he stopped by the house of a physician, John Carpenter, and inadvertently walked off with the doctor's cane. That was September 27.

On October 3, John Walker found Edgar outside Ryan's Tavern in Baltimore. What he had been doing for the last week was - and is - anybody's guess.

Defending Edgar

When Edgar died no one seemed to question his death was from alcoholic misadventure. So why did people change their minds and spend more than 150 years defending Edgar from the charges he drank too much?

Much of the blame has to go to Edgar's successor at Graham's. That was Rufus Griswold. It was Rufus who wrote Edgar's first comprehensive obituary. Written pseudonymously with the name "Ludwig" started out saying, well, Edgar is dead and he was a great author, but since he didn't have any friends, who the heck really cares? Rufus later wrote Edgar's first book length biography which, complete with fabricated quotes, made Edgar look like a deserter from the Army who banged around with his foster fathers' wife and who couldn't have survived without Griswold's help. All in all, much of the negative stories of Poe's character came from Griswold. But oddly enough, Griswold, didn't particularly make Edgar's boozing an issue, probably because the stories were circulating already.

Almost as soon as the ink on Rufus's article was dry Edgar's friends and acquaintances began to write their various "defenses". Contrary to popular opinion, Edgar does not appear to have been a doper although virtually everyone took opium as a medicine at one time or another. But the story that he couldn't leave the booze alone persisted. As the years went on the defenses got more and more defensive until the people who admitted Edgar drank too much began to rationalize that, yes, he did drink too much, but he didn't really drink that much, and if he really did drink that much, it wasn't his fault, anyway, because when you got down to it he didn't really drink that much.

Susan Talley was twenty-seven when she met Edgar at her home on his last visit to Richmond. Although she spoke about his courtly and gentlemanly manner, his dynamic reading of his poetry, and his sense of humor, she also spoke of the times he had clearly had imbibed too much booze. So when Edgar died it's not likely she questioned the official diagnosis.

Later, though, Susan changed her mind and started talking about deep dark plots against Edgar. It was no secret that few in Elmira's family were happy with her plan to marry Edgar. Her kids - not atypically - resented the idea their mom was going to marry a stranger and when Edgar showed up they made fun of him behind his back. But Mrs. Shelton's brothers supposedly were even more opposed to it, thinking Edgar was just a gold digger. It seems to have been Susan that first proposed that Mrs. Shelton's brothers had followed Edgar from Richmond, and perhaps after making him an offer he probably refused, beat him up. Recently this version of events has been amplified into a full blown murder theory and has been published in a book by a major university.

Not everyone was happy with Elmira's marriage plans.