Alberta Hunter

Alberta Hunter

She sang the blues.

Alberta Hunter's dad, Charles, was a railroad porter living in Memphis, Tennessee, when she was born in 1895. At that time, a railroad porter - an employee who helped passengers with their luggage and assisted them in other ways - was one of the better jobs available for African American men. Naturally his job took him away from his family for extended times, and one day when Alberta was five years old, Charles left never to return. Her mother, Laura, had to break the news that her father had died.

The truth, though, was that Charles had skinned out, leaving Laura to raise Alberta and her older sister, La Tosca, by herself. Alberta remembered her mom as a strict parent, but she realized that was because she wanted her daughters to grow up right. Despite their circumstances, Laura didn't go around feeling sorry for herself. If something had to get done, Alberta remembered, then she got it done.

In late 19th and early 20th century America, life for the proper African American families centered around the church. Laura and her own mother took the girls to the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church in Memphis and Alberta remembered sitting in the pews with her grandmother and belting out the hymns.

Early on Alberta showed an onery side. She admitted stealing collection-plate pennies from younger girls, and she and her chums would take the money and buy ice cream. But she soon abandoned her reckless ways and found she could make more money by helping out at the local laundry.

It was a given that you could do better in life if you had an education and Laura was determined her girls would go to school. But Alberta decided to go even before she was old enough to officially enroll. She'd go into a classroom and just sit in an empty desk and listen. The teacher, Minnie Lewis, let her remain knowing that was a better place to be than out on the streets.

The families who attended the CME church were of the solid middle and even wealthy class from the African American community. They were postal workers, teachers, doctors, lawyers, as well as practitioners of other respectable but perhaps not quite typical professions. Alberta remembered that one of the parishoners was the local undertaker, Levy McCoy. Levy exhibited his skill by having one of his - ah - customers propped up in his funeral parlor "deader than a doornail, honey1."

Footnote

This unusual story was confirmed by a writer who discovered the reference in a book published in 1908 by G. P. Hamilton, one of Memphis's early African American educators and civic leaders. In The Bright Side of Memphis Mr. Hamilton wrote:

Many undertakers are not very skillful, but Mr. McCoy is a happy exception to this rule. In his establishment may be seen the remains of a man in a state of perfect preservation, notwithstanding the fact that the man died several years ago. The remains of this man are on exhibition and may be seen at any time by those who wish.

Memphis itself was a center of black culture. William Christopher Handy - "W. C." to his friends and the composer of the Saint Louis Blues - had settled in Memphis where he started a music publishing company in 1906. Naturally Mr. Handy had formed his own band, and Alberta would watch as they marched by and would attend W. C.'s free concerts in Dixie Park.

Unfortunately Alberta's birth also corresponded to the enactment of increasingly repressive Jim Crow laws. In 1905, Memphis passed an ordinance that all black people had to sit in the back of the streetcars behind a sign marking off the white section. Alberta would climb into a streetcar, pull down the sign, and sit where she pleased.

W. C. Handy

He set up in Memphis.

As she got older, Alberta realized her opportunities in Memphis were limited. Then she heard that one of the older girls, Ellen Winston, had gone to Chicago and had written back that singers were making ten dollars a week.

Well, everyone had told Alberta she could sing well, and in 1911 one of her teachers, called by her students Miss Florida, said she was going to Chicago with her husband. When Alberta said she wished she could go along, Miss Florida said she had a free pass that was good for a kid. If Alberta got permission from her mother, she could go along.

Knowing her mother wouldn't go for it, Alberta just borrowed some money from a friend and showed up at the train station. Although Alberta was sixteen - in that time and place practically an adult2 - she was small and looked much younger. The conductor took the pass without question.

Footnote

The concept of the teenager did not really come into being until the 1950's. Before that once you were out of grammar school - grades 1 to 8 - many kids, particularly from poorer families, went right into the workplace.

Alberta managed to find Ellen (who had changed her name to Helen) and got a job working in the kitchen of a boarding house. She would send money to her mother who was soon satisfied that her daughter was able to take care of herself.

But being a kitchen worker was not why Alberta came to Chicago. She wanted to be a singer. So at night she began going out and trying to find the hot spots and tried to get auditions with the club owners.

Well, a young girl who could sing in church to her friends' satisfaction was not necessarily what a Chicago club owner wanted to entertain his patrons. It wasn't that Alberta couldn't sing but she tried to sing as a soprano when she was naturally a contralto. When she did get a chance to sing, the customers - who were largely white - doubled up in laughter. Besides Alberta looked so young, the owners thought if the cops showed up and saw Alberta they'd shut the place down.

At one club Alberta struck up a friendship with Bruce, the piano player who was the only black employee. She asked if she could sing but the manager told Bruce no way. But Alberta kept going back and finally the manager said, OK. He'd offer her ten dollars a week - three bucks more than she was getting for working in the kitchen.

To call the establishment a "club" is being polite. It not only offered drink and music but there were also accommodations where the men could find privacy with their lady companions. Alberta, though, said she was only a singer and no one bothered her. In any case, the place shut down after two years.

Her next job was at Hugh Hoskins, a small club that catered to black clientele. There, too, were ladies who would come in to provide solace for the men. In their time off (no joke intended), the ladies would go downtown and in the jostle the crowd relieve the strollers of their wallets.

Back home in Memphis, Alberta's mom, Laura, and Memphis's other African American citizens were finding fewer and fewer charms in the South. In fact, it was getting rough. The black citizens were heading north, and in 1914 Laura moved to Chicago to stay with Alberta. Fortunately Alberta's ten dollars a week was enough to keep both of them going.

Alberta's business model was to prove her ability at one club and then move up to swankier and swankier places. Her job after the Hugh Hoskins Club was at the Elite Number One Club. The owner, Teenan Jones, was also a pawnbroker and let Alberta select a diamond ring from his shop. He expected her to pay for it but Alberta - laughing about it years later - never did. In 1915, she then moved on to a really high level club, the Panama Café.

The Panama Café only permitted white customers, most of whom were from the uppercrust areas like Hyde Park. This meant better tips for Alberta - which were sometime more than a week's wage. But even after her show - which ran from 8 to 12 - Alberta would go and sing at the after-hours spots. On one of these later excursions, Alberta met a young visitor from New York named Lottie Tyler. Lottie was from New York and told Alberta if she ever came East to stop by.

It was in 1917 that Alberta got a particularly good job at the Dreamland Ballroom which featured King Oliver and his band. She started off at $17.50 a week and in five years was getting $35. This was really moving up. Alberta also kept working at other clubs when not at the Dreamland.

After 1918, the nature of the clubs changed. That year the United States had decreed by constitutional amendment that the manufacture, sale, and transport of alcoholic beverages was to be prohibited. Although it wasn't specifically illegal to drink in a club, to get the booze someone had to manufacture, sell, and transport the stuff.

Among those willing to move, sell, and transport were, of course, the gangsters. These were - ah - "gentlemen" - like Dion "Deanie" O'Banion, "Machine Gun" Jack McGurn, and Alphonse "Scarface" Capone. Among the restaurants that used what Al manufactured, sold, and transported was the Burnham Inn in South Chicago, an establishment where Alberta would perform.

With the gangsters around, the clubs could be hazardous to your health. During one performance, the lights suddenly went out. There was a loud bang and when the lights went back up, there was a dead man at Alberta's feet.

Alberta was soon branching out to other towns, one of which was Covington, Kentucky. Covington was one of the country's biggest gambling towns where Cincinnati's big spenders made the short hop across the Ohio River for a hot time3. But as the casinos were generally in the back of what were nominally nightclubs, the official entertainment was a floor show. Besides you couldn't gamble all the time.

Footnote

By 1911, gambling had been prohibited in all 50 states. It wasn't until 1931 that Nevada relinquished its ban and permitted casino operations. With a few special exceptions, legal gambling was not permitted in other states, whether in private games, in private clubs, or in public, until 1978 when New Jersey opened its first casino.

What is not common knowledge is that some states still prohibit private or "social" games - including some states that have legal casinos. So although you might have a casino within a mile or so of your house, you might not be allowed to have some friends over for penny ante poker.

In Chicago Alberta had met a young man named Willard Saxby Townsend and in 1919, they got married. She admitted the marriage was at least in part to quell, well, rumors that she preferred same-gender relationships. She also admitted that the rumors were true and it's not even certain that the marriage ever had the consummatio necessary for a full validity within the church.

Years later Willard said the main problem was he didn't want Alberta to keep working as an entertainer - a profession not always deemed respectable. But Alberta had no intention of giving up her dreams of making the big time. Although Willard moved out after two months, the marriage didn't officially end until 1923.

Singing in clubs was fine but better money was to be had if you became a star in the theater. In 1920 Alberta landed a part in a musical revue. She didn't have a major role, but she did attract attention - at least of a sort. Her gown, said one critic wrote, brought gasps from the audience.

This was also the era of vaudeville and Alberta managed to get a one-year contract with the Keith Theaters. Keith was one of the major circuits and years earlier had signed up a young conjurer named Erich Weiss. Eric had indeed hit the big time under his stage name Harry Houdini.

Chicago and the Dreamland Café - by then one of the biggest nightclubs in the country - still remained the base of Alberta's operations. With the bigwigs coming in, her singing had also been attracting the attention of other musicians and songwriters. It was in 1920 that no less a personage than W. C. Handy himself gave Alberta a song to premiere. This was "Loveless Love", and in his autobiography, W. C. said that after Alberta sung the song, a lady handed her a $12 tip.

It was also in the 1920's that the recording industry had largely renounced the old style Edison cylinders for the flat two sided discs. Business really took off. With Alberta's clear diction and easily understood lyrics, it was inevitable that she would cut some sides.

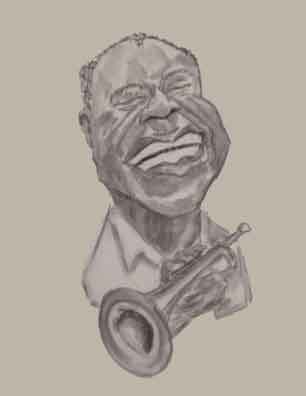

She began recording for both Paramount and Columbia which were big name companies. Among the musicians Alberta recorded with was a young cornet player who had played with King Oliver. That was, of course, Louis Armstrong, known as "Satchelmouth" (or "Satchmo" for short). Then in 1923 Alberta became the first black singer to be accompanied by an all-white band when she recorded "Ain't Nobody's Business If I Do".

Louis Armstrong

Satchmo

The record companies liked to have exclusive contracts. That sounded good but in practice the contracts were crafted as to not always be for the benefit of the singers. The companies got the right to call the shots on how many records were made and how they were marketed. So to beef up her income Alberta - as was common - surreptitiously recorded with other companies and sometimes under assumed names. At least she did until Paramount found out about it and dropped her from their list.

The question was where to go from there. Alberta had been in Chicago for more than a decade. She saw little more the Windy City had to offer. The obvious step up was New York. She headed there in April 1923, and hooked up with her friend Lottie.

Alberta was no longer the girl who sang in church in Memphis. She was an experienced performer in a town where entertainment was the #1 business. She quickly landed a part in a show called How Come? which opened at the famous Apollo Theater.

What isn't well known except to the true cognoscenti of the soon-to-be-called Harlem Renaissance was in the 1920's the most famous clubs that featured black performers - The Apollo, The Cotton Club - catered exclusively to white audiences. The performers had to stay separate from the customers and even had to use the back door. To [heck] with that, thought, Alberta. She went in the front.

There was, of course, venues for the black citizens: Happy Rhone's, the Lennox Club, and the Bamboo Inn. Within a month of arriving in New York. Alberta would appear at these clubs with performers like dancer Bill "Bojangles" Robinson and a former lawyer turned actor and singer named Paul Robeson.

Paul Robeson

Former Lawyer

Alberta had been writing songs since she left home. Now other performers had begun singing them as well (Bessie Smith - the Queen of the Blues - recorded "Down Hearted Blues" for Columbia). Unfortunately, the record companies remained very creative in paying royalties. For years Alberta got no more than a few hundred dollars total.

In 1925 Alberta was again on vaudeville and toured Pennsylvania, upstate New York, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and Ohio. Despite her success, Alberta found the circuit could be rough. Prejudice was still rampant even in the North. Travel was long and grueling and hotel accommodations were rudimentary. Being on tour as part of a group also kept her away from the main centers of entertainment, and so she wasn't getting the publicity of singers like Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey.

But New York remained her base. Manhattan was affordable in those days, and she bought an apartment in Harlem across from the Abyssinian Baptist Church, later to be famous as housing the congregation led by future congressman The Reverend Adam Clayton Powell.

Bessie Smith

In addition to the clubs and music theaters, another venue of entertainment were the informal "rent" parties. You went to a private apartment or other rented room and paid a small fee - a dime or a quarter - at the door. There you could listen to players like Fats Waller and Jelly Roll Morton tickle the ivories. The performers would get a cut of the proceeds.

Ma Rainey

The artists of the Harlem Renaissance also benefited from the time being the era of the patron. Rich artsy people, both black and white, would help support artists. The nature of the support varied with the artistry. Patrons of painters would buy their canvases. Supporters of writers would buy the original manuscripts. Sometimes the wealthy individuals simply paid the artist a stipend or helped them pay their bills when needed.

One of the patrons of the Harlem Renaissance and who benefited Alberta was A'Lelia Walker. A'Lelia was the daughter of the African American cosmetics millionaire Sarah Breedlove who had run the C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company. As a mark of her appreciation Alberta would sometimes take A'Lelia's rich friends to speakeasies where you couldn't get in unless there was someone in the group that the owners knew. Alberta herself, though, neither smoked nor drank.

In the mid-1920's Alberta was recording for Okeh and Victor even though she didn't think they were making enough of an effort to promote her records. On the other hand, the producers said they needed to know when and at what towns Alberta was appearing. With her changeable schedule this wasn't easy.

Then in 1926 a young gentleman named Charles Lindbergh became the 67th man to fly across the Atlantic4. Charles's deed created such a stir that Europe suddenly appeared not that far away. So in 1927 Alberta - telling everyone she was going on vacation - took a boat to Paris with her friend Lottie Williams. They stayed for a brief time at the apartment the African American singer Florence Embry Jones and her husband, Palmer Jones, who were the owners of the Chez Florence nightclub. Alberta and Lottie then moved into a residence hotel which was essentially a short stay apartment building.

Footnote

The first non-stop flight - from Newfoundland to Ireland - was made by Captain John Alcok and Lieutenant A. Whitton Brown in 1919. Later that year the English dirigible, R34, with a crew of 31 made the crossing from Scotland to America. Then in 1924 a German dirigible, ZR3, flew from Friedrichs-hafen, Germany, to Lakehurst New Jersey with thirty-three men on board. That's 66 men before Charles, who was indeed (at least) the 67th man to fly the Atlantic.

But yes, Charles was the first to fly non-stop and alone across the Atlantic. At 7:52 a.m. on May 20, 1927, Charles took off from Roosevelt Field on Long Island and landed at Le Bourget Field in Paris after 33½ hours in the air.

Alberta didn't intend to return very soon from her "vacation". In Europe there was everything that America offered and more. For one thing you could legally buy booze. Wine, of course, was plentiful in France, beer and ales were an English speciality, and the American cocktail had been the vogue in Paris since the late 1800's.

But the big difference is in what there wasn't. There was no racial discrimination. Alberta could go into any club, stay at any hotel, and eat at any restaurant. Best of all, jazz was popular and black performers were welcomed warmly.

But there were limits to what the Europeans would tolerate from the rough-hewn Yankees. Sidney Bechet - known for his cantankerous personality as much as for his virtuosity on the soprano saxophone - got into a dispute at the Chez Florence with guitarist and bano player Gilbert "Litte Mike" McKendrick. When the argument became voluble, Sidney chased Mike to the street. Feeling he hadn't made his point, Sidney pulled a gun and fired (Mike got away). After serving two months of an eleven month sentence, Sidney was put on a boat and sent back to the Land of the Free.

But radio wasn't as common as in America and for entertainment you went usually out. There were plenty of parties and Alberta and Lottie were frequent guests to the Paris elite. Lottie, though, wasn't as enamored of the city as was Alberta and returned to New York after only a few months. Alberta stayed on and when Florence and Palmer left for a visit back home, they put her in charge of the Chez Florenz.

Alberta soon began to receive offers to perform. She played at the the Knickerbocker Nightclub in Paris, the Princess Palace in Nice, and even appeared across the Channel at the London Pavilion at Picadilly Circus.

It was in London that Alberta found new patrons in the likes of Sir Herbert Cook and his wife, Mary. It was at the Cooks' that she met the impressario, Sir Alfred Butt. Sir Alfred was looking for singers to appear in the London performances of Show Boat, the hit musical by Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein based on the novel by Edna Ferber. It was to open on May 1928.

Paul Robeson, whom Alberta had met in New York, had turned down the role of Joe, the Mississippi dock worker, when the show first opened in America. But after some of the more objectionable lyrics were dropped, he agreed to appear in London. Sir Alfred asked Alberta to play the part of Queenie, a young lady who kept giving Joe static.

However, in July Alberta was informed that Queenie was going to be written out. Sir Alfred told her it was by no means due to her performance but only to reduce expenses which he said were getting strained. However just as she was about to return to New York, the decision was reversed and the part of Queenie - which was substantial - was kept in.

The run of Show Boat continued for 350 performances and finally closed in early 1929. Alberta returned to New York on May 22. But she was never one to let grass grow under her feet and over the next fifteen years, Alberta would travel back and forth across the Atlantic many times.

At first it seemed 1929 would be a very good year. Alberta found singing engagements at the clubs and theaters, and even the stock market crash of 1929 had little effect on her fortunes. Things continued to go well, and in 1933 she again returned to Europe. She performed in England, France, Denmark, and during her travels she met a wealthy American, Wallis Simpson and her boyfriend, Edward Windsor, whoever he was.

Alberta remained in Europe for nearly two years and in London she first appeared on the silver screen. This was in Radio Parade of 1935 which was released (despite the title) in 1934. Her part was a minor one and on the credits she isn't listed or simply designated as "Singer".

Her appearance in a motion picture was actually a warning sign. Vaudeville was winding down as movies had become the preferred means of sedentary (and cheap) recreation. Although Alberta continued to find work during the Great Depression, its effects were being felt worldwide. Many of the American expatriates had returned home after their funds dried up. European citizens were also grumbling about foreigners competing for their jobs and on January 12, 1935, the British Ministry of Labor refused to renew Alberta's work permit. She returned to Paris for a short time and then sailed for New York.

During her time in Europe, Alberta had seen things she didn't like. The growing xenophobia of the German government led by the grandson of Maria Schicklgruber worried her.

Once back in New York, though, she found things weren't so rosy either. Racial prejudice had been growing and some white merchants were refusing to hire black workers although they had in the past. Also Harlem was no longer the fashionable area it had been and more and more of the clubs were closing down. After less than six months, Alberta was back in Europe.

The European governments had realized they had messed up in discouraging the American performers. People still wanted to hear authentic jazz and so Alberta was able to secure the needed work authorizations. She also decided to branch out. After performing in Europe for a while, she spent two months at the Continental Cabaret in Cairo (naturally she saw the Pyramids and the Sphinx).

In 1936 Alberta managed to return to London for some performances on BBC Radio. She traveled across the Irish Sea to appear at the Theater Royal in Dublin and the Savoy in Limerick. Even though Italy (and Ethiopia) groaned under the iron hand of a former school teacher named Benito Mussolini, Alberta accepted offers to perform on the Italian Riviera.

It was also in 1936 that Alberta hit a true milestone. She appeared on BBC televison - yes, BBC televison was around that early. She also accepted an offer from NBC to perform on a shortwave broadcast to America. The broadcast was such a success that the NBC executives asked her to return to New York. However she wanted to stay in Europe.

It was a strange time. Job offers kept coming in (Alberta appeared at the Club Harlem in Paris) but the politics were tense. In 1937 when some friends of Alberta were to perform in Berlin, because of their race they were were immediately deported nonstop back to America.

Alberta returned briefly to New York to take up the offer from NBC where she had her own radio program. The show was unexpectedly short lived and in early 1938, she (again) was back in Europe. Alberta performed at The Hauge in the Netherlands, Paris, and - amazingly - even in Berlin and Rome.

Then in March Hitler annexed Austria. He was no longer fooling anyone and in September the American Embassy advised all American citizens to return to the Untied States because of the "complicated situation" in Europe. Soon Alberta was back in New York.

Radio was now well-established as the #1 stay-at-home entertainment. But Alberta found opportunities began drying up. This wasn't just because 1938 was nearly as grim a depression year as 1934. Because the shows were financed by major businesses, fewer companies were willing to sponsor anything featuring black performers.

So if anything prejudice was worse than ever. In 1939 because of objections of the Daughters of the American Revolution the operatic singer Marian Anderson was refused the use of Constitution Hall in Washington. The decision prompted Eleanor Roosevelt, a longtime member of the DAR, to resign from the organization.

With one of the most lucrative performing venues increasingly unavailable, Alberta decided once more to return to Europe. But getting her passport renewed proved impossible even though she wrote directly to Secretary of State Cordell Hull.

Then in December 11, 1941 - yes, December 11 - Germany declared war on the United States. With Europe out of reach, Alberta accepted offers to perform even in the South. She sang in New Orleans, Nashville, and Fort Worth.

Alberta soon began dropping hints that she might want to settle down to a nonperforming career. In early 1943 Alberta was sworn in as a civilian defense volunteer and began working as a laboratory technician where she assisted Jesse Bullova who was professor of internal medicine at New York University. Among other things she ran EEG's on patients and was noted as an "extremely conscientious worker".

But performing was too much of a lure. She appeared for a year at the Garrick Lounge in New York, and in 1944, Alberta joined a USO tour. They traveled to Casablanca in Morocco, Cairo, Karachi (then in India), Calcutta, and Burma. When visiting hospitals Alberta would help wounded soldiers write letters home.

Traveling with the USO show wasn't cushy. The performers flew in cargo planes where the doors were left open so the crew could drop supplies to the troops. Even on the ground life was Spartan. In one performance they sang from the back of a truck where the soldiers used their flashlights to illuminate the "stage". The troupe sometimes came under fire and had to make a beeline to the foxholes. One of the performers leaped into a hole and only later found he was sharing it with a large boa constrictor. The two, it was reported, "departed amicably".

But not all was amicable even when it should have been. The USO entertainers carried the rank of captain and were permitted to eat in the officers mess. But Alberta and the other black performers were told to eat in the kitchen. It wasn't until the Korean War that President Harry Truman ordered desegregation of the armed forces.

The war in Europe ended in May, 1945, but Alberta and the others remained to entertain the troops who were waiting for transportation back home. They first played in France, and one night they were suddenly told to get ready to go to Frankfurt-am-Main in Germany. There with other stars like Mickey Rooney, Jack Benny, and Marlene Dietrich, they performed for General Dwight Eisenhower. But Alberta was particularly miffed to learn they were expected to sing the old saws like "Old Susannah" and "Swing Low Sweet Chariot" instead of the jazz and blues songs she liked. After additional performances around Europe - including a side trip to Berechtesgaden where they saw the remains of Hitler's Eagle's Nest mountain - they returned to New York in November, 1945.

Back home Alberta didn't confine her activities to the East Coast but traveled across the country even as far as Portland, Oregon. Her pay was variable - sometimes as high as $875 per week or as low as $125. Her fees, of course, also had to supply funds for rooms and travel. But that still wasn't bad pay.

Despite her success, Alberta never seemed to be listed with top performers like Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday, Sarah Vaughan, Lena Horne, or Pearl Bailey. Nevertheless she was the first black performer to appear at Boston's opulent and high class Stork Club.

When she toured the South, though, she found things worse than before. If the group ate at a restaurant, Alberta and the others had to go to the kitchen. Sometimes the buses stopped in the middle of nowhere and the black performers had to get off because white customers needed their seats.

The Best Years were brought to an end in 1950 with the invasion of the Korean Peninsula by China. Alberta again joined the USO and entertained the troops there and on Japan and Okinawa.

Since the 1920's Alberta had appeared in shows and at clubs and made records. Although a successful performer by any definition of the word, she had never been a really big star. Some parts had been frustratingly small and as she approached sixty, the roles weren't getting any bigger. In January 1956, she appeared in the the play Debut which starred Inger Stevens (famous to Twilight Zone fans from The Hitchhiker). Alberta's part required her to remain offstage and sing spirituals before each scene.

When the play closed in early 1956, Alberta decided to pack it up. She figured she had gone as far as she could go. This wasn't true, as we'll see, but for now she decided to look for a new career.

In 1955 and after her mother had died Alberta had begun volunteering at the Joint Diseases Hospital. This work didn't interfere with her performaning which was mostly done at night. Still, it was pretty impressive that while approaching senior citizenship Alberta was able to put in nearly 2000 volunteer hours in one year. She had enjoyed the work so why not go to school and become a licensed practical nurse?

There was a wee bit of a problem. At age 61, Alberta was too old to be admitted to the training programs. Fortunately, her obvious sincerity and interest made a good impression on the director of the YWCA school for practical nurses, Phyllis Utz. Phyllis decided to help Alberta out. As there was no real documentation for Alberta' age - no birth certificate or baptismal certificate - Phyllis simply lopped twelve years off her age.

Alberta graduated on August 14, 1956 and completed her internship at Goldwater, Harlem, and Bellevue Hospitals. She received her certificate on April 23, 1957. After passing her boards, she was granted her license on August 4 and was hired at the Goldwater Hospital.

Despite what you read on the Fount of All Knowledge, Alberta never entirely abandoned singing. In 1957, Langston Hughes, now a famous poet and author, wrote her that United Artists was interested in her making a record. She usually turned such offers down although once, in 1961, the jazz critic Chris Albertson remembered her and found her name in the phone book. He persuaded her to make some records for the Prestige label.

Although her voice was deeper than in her earlier years, Alberta could still sing and she when she did she would get good notices. In 1971, Alberta was persuaded to appear on the television show, Faces in Jazz. Her pay was $1000 - about twice what she made in a month at the hospital.

By January 1977, Alberta had been a practicing practical nurse for 21 years. That month the hospital told her that she was scheduled for retirement. Since she had enough accumulated leave to take her to her birthday she didn't need to come in to work any more.

Alberta could have requested an extension - she had really liked being a nurse - but New York was going through one of its many budget crises and no retirement extensions were permitted. At her retirement party the tributes were fairly standard employer fare and actually Alberta was irritated about having to retire. But the hospital had mandatory retirement at age 70. Actually Alberta would be turning 82.

The day of her retirement party she received a note from Bobby Short, a pianist at the Café Carlyle. There was going to be a party for Mabel Mercer, one of Alberta's friends from her performing days. A lot of jazz people would be there and Mable asked Bobby to invite Alberta.

Not many of the people there had met Alberta personally and they wondered who the fancy dressed elderly lady was. Charlie Bourgeoise, a public relations man for numerous jazz events, introduced himself as did the songwriter Alec Wilder. As they talked Alberta said she had written some songs and Charlie asked her to sing some. She obliged with "Down Hearted Blues". After the song she mentioned her name and Charlie realize he realized he had been talking to the well-known blues singer from years past.

The next day Charlie called restaurant owner Barney Josephson. Knowing that Barney's restaurant, The Cookery, featured live performers, Charlie praised Alberta's singing. Barney knew who Alberta was but didn't realize she was still around. He called her up and said he was going to have her appear in three weeks. She said she'd agree if he'd act as her manager. Charlie said fine.

If you listen to Alberta's later recordings you can realize why her appearance was a success. Her opening had attracted a number of jazz celebrities, including Eubie Blake who had turned a sprigtly 94 years old. Barney turned out to be an honest man who treated Alberta well - both personally and professionally. In fact, he never even deducted a manager's 10 percent from her fees. Recognizing it was a rare club owner who would book an 82 year old singer, for the rest of her life Alberta used The Cookery as her base of operations.

From then out Alberta had a second career which was even more successful than her first. In October, 1977 the New Yorker ran a profile on her and she appeared on (yes) television as a guest on To Tell the Truth, The Dick Cavett Show, The Mike Dougas Show, Good Morning America, The Merv Griffin Show, The Prime of Your Life, and even - this was the big time - Sixty Minutes.

Alberta wasn't picking up chicken feed either. She was given $2000 for some taped interviews with Chris Albertson, and when she sang some songs for movie soundtrack she got $20,000. The sponsors of Final Net hairspray paid her $15,000 for singing on a commercial. She hadn't made that much in a year when working as a nurse. This was the time when James Earl Jones was paid $9,000 for the one day needed to voice the part of Darth Vadar in the first Star Wars movie.

What was working to Alberta's advantage was she was dealing with honest business partners. John Hammond, the well-known record producer, had put her in touch with a copyright lawyer who registered all her songs. So she finally began to get the royalties due her.

On March, 1978 the Tennessee House of Representatives voted a resolution praising Alberta for her contributions to the arts and commented on her fine voice. When she performed in Memphis she was given the key to the city, and in June she appeared at Carniegie Hall,

Performing six nights a week wasn't easy for anyone, but all the more impressive for someone in her eighties. She still managed to squeeze in an invitation to the White House where she sang for Jimmy and Rosalind Carter. Once she even got a letter from the Reverend Dr. Norman Vincent Peale, for crying out loud! He had seen her performance at The Cookery and said how much he liked it.

In 1979 Alberta took off on a national tour although some were concerned that at 84 it might be too much of a strain. She did check with her doctor before she appeared at the concerts, and in 1982 she returned to Paris after more than thirty years. She also appeared in Zurich and at the Berlin Jazz Festival. A year later she made a trip to Brazil.

Alberta was, we must remember, over eighty. In 1980 she had a fall and broke her shoulder and hip. She recovered but she clearly had to start slowing down.

In December 1982 Alberta got another invitation to the White House. However, she had been feeling poorly and instead checked into a hospital. It turned out she had gangrene in her intestine and an operation was required. She stayed in the hospital for two months but but found some solace when she read a nice article about her in Time Magazine. She resumed her touring when she got out.

In August she was able to fly for yet another show in Sao Paulo, Brazil. But she had trouble moving about on her own and by the end of the year she had to be practically carried onto the stage. In the summer of 1984 she appeared in Denver, but had to stop before the performance was over.

Back in New York she was admitted to St. Vincent's Hospital. She had to be fed intravenously, and by September she was down to 85 pounds.

Alberta was able to return to her apartment in October. Earlier she had a pacemaker installed, and on October 17, one of the company's employees called to reminder her she hadn't been in for some scheduled tests. There was no answer, and a friend, Harry Watkins, was asked if he could contact her.

When Alberta didn't answer the phone, Harry called her pianist, Gerald Cook, who went to Alberta's apartment. He found her in her pajamas sitting in an armchair. She was 89.

References and Further Reading

Alberta Hunter: A Celebration in Blues, Frank Taylor (with Gerald Cook), McGraw-Hill, 1987.

The Bright Side of Memphis: A Compendium of Information Concerning the Colored People of Memphis, Tennessee, Showing Their Achievements in Business, Industrial and Professional Life and Including Articles of General Interest on the Race, Green Polonius Hamilton, G. P. Hamilton, 1908.

Radio Parade of 1935, Arthur Woods (Director), British International Pictures, 1934, Internet Movie Data Base.

Ripley's Believe It or Not: A Modern Book of Wonders, Miracles, Freaks, Monstrosities, and Almost-Impossibilities Written, Illustrated, and Proved by Robert L. Ripley or [signed] Ripley, Robert Ripley, Ripley Publishing, 1931 (Reprint 2004, Ripley Entertainment, Inc.).