Auguste Rodin

Auguste Rodin

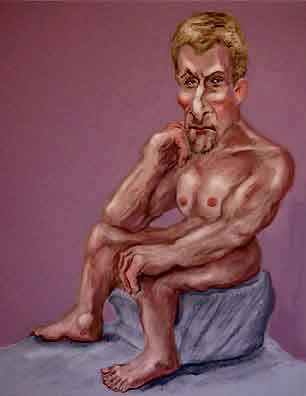

What was he thinking?

Despite what he implied in his old age, Auguste Rodin was not a poor waif from the lower echelons of Parisian life. His father was a member of the Paris police force and not just a simple patrolman. Papa Jean-Baptiste Rodin worked mostly in the administrations and although not a wealthy man, was of the respectable, albeit admittedly lower, middle class. He was able to send young Auguste to a boarding school (run by his brother) and was concerned that young Auguste wasn't interested in much anything other than drawing. Although the expense at Uncle Rodin's school was usually cited as the reason Auguste returned home as a young teenager, it is more likely that problems with his reading and mathematics prompted the young man to want to embark on an artistic career. Today dyslexia is usually diagnosed in children who have difficulty in reading and arithmetic, but in Auguste it was - as he himself said - his severe short sightedness (as myopia was called then) that caused the problems. Oddly enough, that wasn't such a problem for an artist. Small detailed work could be done by just moving the object closer to your eyes and in larger sculpture detail wasn't really necessary.

Auguste started studies in École Impériale Spéciale de Dessin et de Mathématiques. This was usually called the "Petite Ecole" and was a school for the artistic craftsmen as compared to the "Grand Ecole" of the Beaux-Artes which was fine art school of France. Auguste later tried to enter the Grand Ecole but did not pass the entrance exams.

Failure to enter the Grand Ecole did not mean he couldn't become a haute-artiste, as you could also learn art as an apprentices to an established artist. Auguste admitted he himself passed up the opportunity to work with some of the most prominent sculptors of the day. But with his skill he had no problem finding work making decorative art, and he joined a local art society where his work sculptures received considerable compliments from more established artists.

By the time he was a young man, Auguste was working as an ornamental artist by day - an ornemaniste - for five francs a day and working on his sculptures in evening and Sundays. The pay wasn't much, but it was certainly something a single artist could live on. Auguste knew how to live frugally and keep expenses down, particularly since he, unlike most of his contemporaries, didn't smoke.

Auguste had a lot of trouble with his sculptures. After he had made the prototype models in clay, they would oft times sit in his studio, gathering dust (and sculpture studios can indeed be dusty and messy places). It wasn't because the sculptures weren't good. In fact, one of his early submissions to the famed (and prestigious) Paris Salon was so realistic that he was accused of actually making the molds from a live model. Instead, it was simply that he didn't have enough money to pay someone to make the final sculpture.

Hanh????!!!! You mean Auguste Rodin - one of the greatest bronze sculptors in history - just made the prototype models? Then he hired other artists to actually make the statues that we see in the most famous museums throughout the world? What the hey?

That is indeed the case. Auguste was largely a clay sculptor and virtually everything he made with his own hands were clay models. Few if any of his own hands-on work survive. Not only that, but some of the - quote - "original" - unquote - Rodins you see in museums were actually cast only after Auguste passed onto the great foundry in the sky. When some people learn that Auguste didn't even make the actual statues gracing the various museums, they are shocked! shocked! and you have to ask what does it really mean for a Rodin to be "original"?

But before anyone goes into spittle flinging diatribes about how Auguste was "cheating", remember that bronze statues aren't made by pounding bits of bronze together or taking a big block of bronze and cutting away the parts until it looks like what you're trying to make. No, bronze statues are in fact casts made by pouring molten bronze into a mold.

There are various ways to make the molds and some have been around for thousands of years. One of the lowest tech is sand casting where the statue (or parts thereof) are put into frames which are packed with sand. With the right amount of moisture and extreme care, the frames can be separated and the model removed, leaving its impression in the sand. After adding channels and flues to the sand bed, the frame can be reassembled and molten bronze poured into the cavity leaving the actual bronze cast.

However in sand casting, though the least expensive method of casting, requires finesse and the sand molds can easily fall apart before or during casting. You also have to pour the bronze as soon as you make the mold. So the preferred method for casting is to make the mold from a refractory ceramic material. This type of mold - usually called a "shell" - is made by coating a wax model of the sculpture with a colloidal suspension of silica followed by a layer of sand. You let those layers dry and repeat the two steps. After about ten layers of alternating silica with sand of increasing coarseness, let the mold dry in air for a few days. Then you burn out the wax and end up with a very hard mold that can withstand the 2200 degrees Fahrenheit of molten bronze. Of course, the wax model also has to be designed so that the bronze will flow freely into the mold and air won't get trapped. At times the final wax model is so complex that you can hardly see the sculpture for the vents and sprues. For a quick run through of the bronze casting process (in a new window) click here.

Well, then how do you make the wax model? Well, of course you can make the sculpture directly from the wax. Or - as is often the case, you can make a wax cast from another mold. In Rodin's day the molds for the wax models were usually plaster "piece" molds - that is, molds made in pieces that would fit together snugly so you could pour wax into the mold, but could then be taken apart without damaging either the statue or the mold. That way they could be used again to make further "editions" of the sculpture. For complex works with lots of "undercuts" a single mold might have 60 to 100 separate pieces. Such a mold often left ridges on the bronze which are usually ground off or "chased". However, Auguste sometimes would leave the ridges there, and they became something of a trademark.

The piece molds were often made, not as you might think from the original clay model, but from another cast - which in Auguste's time would have been made of plaster. And no, Auguste did not make the plaster models himself from the original clay that had been fashioned with his own hand. And yes, you needed another mold to make the plaster model. That mold was typically what they call a "waste" mold and was also made of plaster. That is you made a plaster mold around the clay and after separating the mold from the clay, you then poured in the liquid plaster. After the plaster set, the outer mold was removed by chipping it away from the cast. Naturally this destroyed the mold - hence the name "waste" mold. But to be able to chip a plaster mold away from a plaster cast, you had to grease up the inside of the mold although today you usually spray in a silicone mold release. But it was this plaster model that were usually preserved by the artist for future reference and use. Today many of Auguste's original plaster models are still around, many officially owned by the French government.

Why make the plaster model at all? Couldn't you just make the piece mold from the clay? Well, yes and no. In unfired clay the particles are simply held together by adhesion and the figure is quite fragile. Worse, even when dry there is usually enough water in the clay that if the temperature drops below freezing the statue will break apart. That happened to one of Rodin's first serious pieces, the Man with the Broken Nose.

So unless you fire a clay statue to produce terra cotta, it would not be very durable and will soften when you coat it with the wet plaster and comes apart when you separate the pieces of the mold. In fact that's the advantage of the waste mold. Since you can tear the clay model apart you don't need as many pieces for a waste mold as you do for a piece mold. A waste mold might be constructed in only two parts while the piece mold on even a simple statue could have ten pieces. The plaster was intended to be a permanent model for future reference. Yes, plaster can be broken and chipped, but also easily repaired. In the 19th century it was was about the best material they had.

Today plaster piece molds are not the norm. Instead you usually do make a mold for the wax directly from the clay. But modern molds are made in two stages: first you make a flexible "inner" mold and then to hold the inner mold in place and to keep its shape you fashion a rigid "mother mold" outside. But even here there are multiple steps.

First after the clay model dries, you coat it with a layer of shellac. Then you coat it with a mold release. In days of yore this was vegetable oil or vaseline, but now is almost always a sprayed-on silicone compound. You then make the inner mold from a liquid rubber (latex, silicone, or urethane). There are various techniques for adding the rubber, but often it is simply brushed on in multiple coats and allowed to dry.

The next step is to make the "mother" mold. The mother mold is just an outer shell that the holds the rubber mold in place. But since rubber is flexible you don't need to make the mold into as many pieces as a reusable plaster mold but you do need to make the inner mold so the undercuts are filled sufficiently so the mother mold can be removed. Many rubber molds can be made into two pieces, but a complex sculpture will have more. From this mold you can make models in many materials. Some permanent models are still made of plaster, but more and more often sculptors use plastic resins which are much less fragile. Needless to say many details are omitted here and so 'ere anyone tries this at home, it is imperative to seek professional instruction.

So from this rather convoluted and long winded description, you can see that for Auguste to get a final bronze statue, the routine was:

Clay Model → Plaster "Waste" Mold → Plaster Cast → Plaster "Piece" Mold → Wax Cast → Ceramic "Shell" Mold → Bronze Cast → Assembling the Pieces → Grinding and Polishing → Patina

Yes. Auguste would do Step 1 and turn the rest over to his assistants and hired specialists.

Lest the readers loose all faith in mankind, Auguste was simply following the usual modus operandi then and to a large degree now - particularly for a well-to-do artist with good connections and plenty of commissions. After all, bronze casting requires specialized - and quite costly - equipment. Certainly some sculptors take an active part in the casting - they are on hand when the bronze is cast - but it is just as likely they will simply have the model taken to the foundry and leave the job to the specialists. Even the final finishing and "chasing" of the metal surface, polishing, and the adding of the final chemical patina may be done with the artist not present. Still it is quite legitimate to call the final bronze an original by the artist.

Where the big surprise comes to today's art fans, though, is that Auguste didn't just hire the foundry to cast his bronze statues. Certainly after reading the trials and tribulations of casting bronze, Auguste's delegating the metal work to others is understandable. But the big shocker is that if you see a stone sculpture by Auguste, it is a sure bet he didn't carve that by his own hand, either. Instead as with his bronze statues, Auguste hired specialists skilled in stone carving to make the final pieces. True, in his earlier years Auguste would make a very detailed model in clay and the assistant might point the sculpture using a pointing machine to help replicate the model exactly. But later Auguste might just rough out a clay "sketch" and then supervise and instruct the assistants - often literally looking over their shoulders - in what to carve.

Michelangelo did a lot of the work himself.

The degree of which artists rely on hired help varies. Even Michelangelo - often believed to be a solitary work-by-himself artist - always had a number of assistants, and he would hire even more help on a job-by-job basis. For his work on the Medici chapel he hired over a hundred workers and these included stone carvers. Despite the trumpeting that Michaelangelo painted the frescoes on the Sistine Chapel without having any experience in painting, much less in the difficult fresco technique (he was a sculptor, not a painter we hear), that is, alas, not true. Michaelangelo would indeed provide paintings for private clients - most famously for the marriage of Agnolo Doni and this was before he painted the Sistine ceiling (to see the painting - the "Doni Tondo" - in a separate window click here). Also as a teenager, Michelangelo studied with Domenico Ghirlandaio, the greatest fresco painter of the time, and so knew the basics of the technique. But even then when it came to doing the Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo realized his lack of experience was a drawback. So he hired a number of fresco specialists to help him - the usual number is five. Michelangelo - being Michelangelo - quickly got up to speed and toward the end of the job he was doing most of the painting himself.

Still in a lot of ways Michelangelo and Auguste are a lot alike. Even Michaelangelo would sometimes "rough" out a sculpture and then let an assistant finish it. Sometimes, though, the assistant would do such a rotten job - such as when Michelangelo carved The Risen Christ - that Michaelangelo would have to refinish the finishing. But still Michaelangelo did do quite a bit of the carving with his own hand. Eye witnesses said his ability was incredible, knocking away huge chunks of marble with a speed and precision that defied belief. On the other hand if you go to a Rodin exhibit, remember that Auguste did not actually make the object you are seeing - whether stone or bronze - a lot of credit should go to the ability and talent of the assistants.

Auguste himself recognized his hands off approach made the definition of a - quote - "original Rodin" - unquote - a matter of, well, a matter of definition. When the famous art dealer, Ambroise Vollard, asked Auguste how you can tell if a Rodin was really a Rodin or not, Auguste said "It's quite simple! A true Rodin is one that has been cast with my consent. The false is done without my knowledge."

However, Auguste, then threw a monkey wrench into the blast furance when he left all his casts and models to the French government. He made no restrictions on the number of reproductions, and so you can argue that anything made from one of these original casts is indeed with Auguste's consent. But when you see a Rodin that was cast in 1925, it's hard to say that was actually with his knowledge. Fortunately, the French government has since then made a rule defining what is an original bronze. You can have eight copies made from a single mold - two proofs and six casts - and you can call these original. After that, anything else is a reproduction even if cast from the original models or molds.

Like assisants, everywhere Rodin's helpers ranged in skill and so were assigned tasks appropriately. The less experienced carvers would take a the clay model and rough out the general shape in stone. Then the statue would be turned over the practiciens, a term used for the most skilled of the assistants. The assistants worked hard too, and a typical workday in Rodin's atelier was 12 hours at about a franc an hour. So if you worked full time for Rodin you could end up with 3000 francs a year.

Like all employers, Rodin no doubt felt he was paying his workers adequately, even generously. And indeed, 3000 francs a year was certainly sufficient to cover living expenses in nineteenth century metropolitan France. You could afford and apartment and have enough left over for trips to the cabaret, museums, and the occasional night out. On the other hand, during the same era, the hardrock miners working the Comstock Lode had an eight hour day and were paid four dollars a day - about twenty francs - and so were earning about twice what working for Auguste would have brought them.

So it's not surprising the practiciens developed mixed feelings about working with Auguste. They certainly appreciated their bosses creative talents and the opportunity for working for someone who even then was a living legend. But it was still irritating if you did all the hard work and saw the final signature was Rodin. At the same time working with Auguste - whom none doubted was a sculptural genius - was worth the aggravation. At least for a while.

You do begin to wonder, though, who should get credit when you realize that some of Auguste's assistants actually made the clay models or at least parts of them. Among Auguste's assistants were two young women, Jessie Lipscomb from England, and Camille Claudel. Both were excellent artists. Camille was particularly skilled in sculpting the human form, and Jessie specialized in modeling drapery and clothes. Auguste asked Camille to model the hands of his famous Burgher's of Calais, and Jessie worked on the robes. Originally Auguste was going to have the Burgher's wandering around naked but he changed his mind.

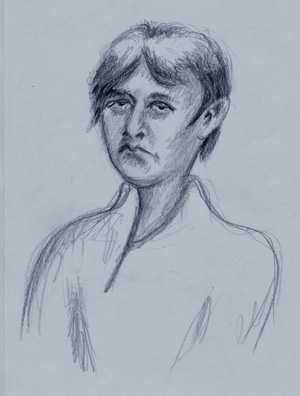

Camille Claudel

Le Practiciene.

Jessie was by no means homely and eventually married, but she did have a rather schoolmarmish look. Camille on the other hand was - shall we say it? - a hot babe although she had a tendency to appear worried and melancholy. Auguste soon became quite taken with Camille. Even though he set up housekeeping with his long time girlfriend, Rose Beuret, he began to keep company with the younger lady. And when we say he was keeping company we mean he was keeping company.

At first Camille didn't seem to have problems with the arrangement de trois. But Rose was certainly not pleased. She began to berate Auguste and go into such spittle flinging diatribes about Auguste's new found floozie that Auguste worried Rose would have a heart attack. But Rose had been his companion during his days as a starving artist, and he had no intention of leaving her and their son.

But after a while Camille also began to think that Auguste should make a choice one way or another. She didn't enjoy being a bright and shiny but second hand fiddle for Auguste. So things chez and atelier Rodin began to get unpleasant. After a while it got to the point where at home Ruth would lambast Auguste for his dalliances, and Auguste would leave for the studio where Camille would pepper him with sarcastic comments about his divving up his attentions. Although we can sympathize with Auguste, the problems were really no one's fault but his own.

Eventually things sorted themselves out because Camille wanted to work on her own art, and it became more and more galling for her to be thought of as Rodin's assistant. She also began to resent the fact that many of Rodin's sculpture incorporated so much of her work but there was always the ubiquitous ![]() somewhere on the damn statue. So eventually she moved out and set up her own studio.

somewhere on the damn statue. So eventually she moved out and set up her own studio.

Art critics were impressed with Camille's work which was certainly distinctive from Auguste. Camille's sculptures tend to have flowing lines with the figures moving at angles away from the perpendicular while Auguste's work was more blocky and monumental. Camille's themes also were more about relationships, and Auguste would sculpt naked guys sitting around and thinking. Ater she left Auguste's studio Camille began to have money problems - it is hard to pay expenses from the praise of critics - and Auguste was and continued to be supportive of Camille's ambitions. He did what he could to put her into touch with art connoisseurs, potential patrons, and other influential people. Camille eventually began to receive commissions for work which included requests from the French government.

It should be mentioned - given subsequent events - that Camille had difficulties with her family, particularly her mother. Camille was what in the 1960's and 1970's became to be known as a liberated woman. Although her attitudes were mainstream by today's standards, they were shocking for a lady to have in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Camille and her friends not only wanted to make careers in a man's world, they hung around with the guys and took breaks to have a smoke. Camille also had unorthodox views on morals and religions (she thought the Bible was crap), a view which upset her religiously minded brother, Paul. It was also not possible to keep secret her - ah - "relationship" - with Auguste. Still Paul and her father didn't think that the differences in lifestyle or philosophy should keep Camille from their home. But Mama Claudel - who was something of a shrew on her good days - was scandalized by her daughter's behavior and said she didn't even want Camille around. As we know, if Mama ain't happy, ain't nobody happy, and Camille quit visiting home.

Rodin continued to praise Camille's work and to try to introduce her to important people. But she was afraid that having Rodin as her mentor - even him trying to help her out - meant that people would always think of her as Auguste's assistant. Once when Auguste asked Camille if she wanted to meet the President of France, she said no. Finally she wrote to a friend and told him to pass on the message that Auguste was to stay away from her studio and not contact her.

Camille's behavior began to become erratic and strange. When small problems cropped up that were due to ordinary bureaucracy and simple mistakes, she began to see them as machinations directed against her. Once when a plaster model was not promptly returned after the bronze was cast, she wrote a number of vitriolic letters to the government official in charge. Two of the - quote - "letters" - unquote - consisted of nothing more than cat poop stuffed in the envelopes. Not surprisingly, Camille saw a steep drop in commissions.

What was even more disconcerting to her friends and family is that Camille began to see all her problems deliberately being concocted by none other than Auguste Rodin. He had "stolen" her ideas, she said, and was joining forces with her family to keep her from success. Actually nothing was further from the truth. He had no little contact with her family, and he continued to praise her art and recommend her for commissions.

Camille's state of mind continued to go downhill. It got to the point that Camille locked herself away in her studio and wouldn't let anyone in. Once one of her models showed up for his sitting, and she kept him waiting outside, talking only through the closed door. When she finally let him in, she was carrying a baseball bat studded with nails. She needed the protection, she told him, because people in the pay of Rodin were out to kill her.

Of course, word of Camille's behavior got back to her family. Papa Claudel and brother Paul wanted to take her home, but Mama Claudel was as adamant as ever. She wanted nothing to do with her crazy, immoral daughter. Soon Papa died and Camille's behavior deteriorated to the point where she would work on sculptures and then take a hammer to them, smashing them into pieces, then calling in the dustman to haul the chunks away. Those who were admitted to her studio reported a scene of chaos and "filth", a word used to describe improper sanitary conditions in a day where indoor plumbing was a luxury and chamber pots were sometimes the only convenience All the while Camille kept talking about how Rodin was out to get her.

Paul was worried about his sister, but with four children of his own and a job requiring a lot of travel and social functions (he was consul to Germany), he could not take her in to live with him. So he sadly had the family doctor issue a medical certificate to have her committed to a mental hospital. At this time the family of a mental patient had the say when the person would be released, and it was still thought that the best way for some seriously ill patients was "sequestering" them - i. e., putting them in solitary confinement. But it was also a time when progress was being made in the treatment of mental illnesses. French law was also progressive regarding protecting personal assets of mental patients, and Camille's personal income and property - including her statues and casts - were legally kept in her possession. In the hospital, Camille quickly began to show improvement, and eventually the doctors told the family that it would be helpful for Camille if she could make some visits home. But Camille's mother still said no. She did not want her daughter in her house. So for the next thirty years, until her death in 1943, Camille remained confined to mental hospitals.

Auguste, though, gained fame and glory as one of the greatest artists of all time. He finally married Rose on January 29, 1917. She died fifteen days later, ironically, on Valentine's day. Auguste himself didn't finish out the year, either, and died on November 17.

References

Rodin: A Biography, Frederic Grunfeld, Henry Holt, 1987. The first modern full scale modern (ergo, post-mid-20th century) biography. Quite massive but also extremely readable.

Rodin: The Shape of Genius, Ruth Butler, Yale University Press (1996). This seems to be the most recent biography.

Rodin Rediscovered, Albert Elsen (Editor), National Gallery of Art (1981). Among other things, this volume gives us an idea of what Auguste paid his assistants.

Camille Claudel: A Life, Odile Ayral-Clause, Abrams (2002). The definitive biography, this book is objective and non-accusatory about Camille's life. It certainly does not paint Rodin as the bad guy although it does amplify the point that when you get down to it, Rodin's assistants certainly deserve much more credit for his work than was then (or now) the customary.

There was a movie made about Camille in 1989 starring Isabelle Adjani as Camille and Gérard Depardieu as Auguste - both of whom looked a lot like their real life counterparts. CooperToons has not seen the movie so cannot venture and opinion.