Bob Dylan

Nobel Laureate for Literature

2016

He's so unhip, when you say "Dylan", he thinks you're talking about Dylan Thomas. Whoever he was. The man ain't got no culture.

- Paul Simon

A Simple Desultory Philippic

(Or How I Was Robert McNamara'd Into Submission)

Bob Dylan

The critics would be a-turnin'.

At one time Paul Simon's satirical lyrics were no doubt terribly funny. But now people are likely to scratch their heads at hearing the barrage of now obscure celebrities. As for any message the song is supposed to convey, well, that's been lost to history. About all we can say is the singing was intended to satirize the winner of the Nobel for Literature.

Of course, not the Nobel Prize winner then. In 1966 the Literature Prize had gone to the Israeli authors Shmuel Yosef Agnon and Nelly Sachs. The song was about neither of these distinguished writers.

Instead, the cognoscenti immediately recognized the song as a parody of Bob Dylan. Bob, then only 25, already had seven albums to his credit and was recognized as an important performer and songwriter of the 1960's popular culture. And despite his parody of Bob, Paul and his singing partner Art Garfunkel, had included what was perhaps Bob's most famous song on their (at the time) unsuccessful debut album Wednesday Morning, 3 A.M.

But we do have to admit it. Bob's style of singing is truly sui generis. Even his friends would sometimes imitate his unique vocal characteristics. The folk singer (and later Grammy winner) Ramblin' Jack Elliott met Bob in 1961 and would tell the story that Bob was in the audience when he sang Bob's song, "Don't Think Twice". Jack said after his performance Bob had called out, "I relinquish it to you, Jack!" Of course, in the telling Jack imitated Bob, and you couldn't understand a word he said.

Woody Guthrie

An Influence.

Actually, Ramblin' Jack Elliott imitating Bob Dylan doesn't sound that different from Ramblin' Jack Elliott imitating Ramblin' Jack Elliott. That's because both men's style of singing (and speaking) was heavily influenced by the singing (and speaking) of Woodrow Wilson Guthrie.

"Influenced" is really too mild a word, and it's not unfair to say that Bob and Jack were the most fervent of the verbatim Woody Guthrie imitators. Ramblin' Jack met Woody in the early 1950's. The two men hung out together and traveled around for some time. Jack - whose real name was Elliot Adnopoz - soon learned to imitate Woody perfectly, not just in singing but in conversation. Sometimes people would hear Jack talking in another room and think it was Woody.

Of course Jack didn't just imitate Woody, he adapted Woody's songs into his own arrangements. And we have to admit that Jack was by far the superior musician. Even Woody's friends admitted his playing and singing were often rudimentary. Pete Seeger, who knew Woody as well as anyone, once said, "Oh, he wasn't the world's greatest guitar picker. He could pick a perfectly decent accompaniment. Play a few fancy licks."

Pete Seeger

Woody could play of fancy licks.

Still, it's easy to underrate Woody. His studio recordings are a bit stiff compared to his live performances where he exhibited, if not high virtuosity, then certainly professional showmanship. A 1940 radio program called "Back Where I Come From" which was hosted by the New Yorker critic, Clifton Fadiman, is arguably Woody at his best. It is, though, a bit strange to hear Woody backed by a full orchestra and a four-part classical chorus.

On the other hand, Bob didn't meet Woody until 1961. Bob had been part of the folk scene in the Dinkytown environs of Minneapolis. He had heard Woody's recordings and borrowed Bound for Glory, Woody's rather loose autobiography, from a college professor. Bob became so fascinated with Woody's life and songs that felt he had to meet the man.

But by then the symptoms of Huntington's disease which Woody had inherited from his mother had become so severe that he was a full-time patient at New Jersey's Greystone Hospital. Although Bob tried to call Woody, he was always told that Mr. Guthrie couldn't come to the phone. But Bob learned Woody could have visitors and so hitchhiked from Minneapolis to New Jersey to meet him.

The actual manner in which Bob met Woody is a bit uncertain. Some accounts imply he first visited the hospital and met Woody there. However, another version says that Bob met Woody at the home of Bob and Sidsel Gleason in East Orange, New Jersey.

In 1959 Bob and Sidsel (known as Sid) had heard a radio program of Woody's songs and at the end of the show the announcer mentioned that Woody was a patient at Greystone. He would, though, love to received letters from the listeners. Bob and Sid decided to do more and began driving the 20-odd miles from their home to Greystone to pick Woody up for the weekend. The weekend visits soon become major get-togethers for Woody's friends and family. Marjorie, Woody's second wife, and the kids, Arlo, Nora, and Joady, would be sure to be there, driving from their home on Coney Island.

Bob arrived in New York in January, 1961. He wasn't sure how the hospital would take to a kid just showing up and asking for Woody (Bob was 19 but looked about 16). So he first headed to Greenwich village where one of the clubs had an "open-mike" night. There Bob sang some songs and told the people he had been following the steps of Woody Guthrie. Soon someone gave him Marjorie's address.

Marjorie and Woody's marriage had lasted seven years, and she had since remarried. Her new husband, Al Addeo, was a carpenter and Mary operated a dance studio (she had been a dancer and teacher for Martha Graham). During the day a babysitter looked after the kids, and so they were concerned when a young stranger knocked at the door asking for Woody. After some uncertainty, Bob was invited in and stayed for a short time. A couple of days later he visited the Gleasons and met Woody.

Of course many of the visitors to the Gleason's home were themselves singers, and they would play and sing for Woody and receive his comments. Woody particularly liked Bob's singing. "That boy's got a voice," he said. "Maybe he won't make it with his writing, but he can sing it. He can really sing it."

It seems obvious now that Bob's early singing style and stage persona were directly borrowed from Woody. However, Jack Elliot said that his friends said that Bob was actually imitating him, that is, Jack. After all, by the time Bob met Woody, Woody could no longer hold a guitar or sing.

So Bob had to learn Woody's style from Jack who had known Woody when Woody could still perform. "Other people could see he was imitating me," Jack said, "but I couldn't see it at first. I was imitating Woody, and I was helping Bob to learn how to do it."

Bob quickly changed from being a Woody Guthrie imitator to - quoting the now extinct 1960's jargon - "doing his own thing". By 1965 Bob had already moved from the "pure" acoustic folk tradition into the electric rock and roll sound. That was the year of the (in)famous Newport Folk Festival where Bob came on stage with - gasp! - an electric guitar!!!!! According to some accounts there was pandemonium, part of the audience cheering; others booing. And one story is that Pete Seeger was claiming he was going to cut the wires. That was also the year Bob released Highway 61 Revisited which featured the electric sound and little of the pure folk-acoustic music.

By then, though, Woody was no longer able to leave the hospital and had largely fallen from the American collective consciousness. Parents wondered what had become of Woody and their kids - despite repeatedly singing "This Land Is Your Land" in school assemblies - never knew he existed.

It wasn't until Woody's oldest son, Arlo, had a surprising hit with "Alice's Restaurant" that people read the liner notes and learned that Arlo was the son of the composer of "This Land". Soon Woody's albums began to fill the record bins in a way they never had before.

But then came October 13, 2016.

Most of the "Did Bob Dylan Deserve the Nobel Prize?" articles have been think pieces and ruminate on the question whether Bob merited the prize. Although certainly many people think he did, some of the biggest publications - or at least articles in the publications - dissented. One critic - although not going into spittle flinging diatribes - said Bob was not a poet. He was a songwriter. Not the same thing.

Look at it this way. Samuel Beckett wrote plays, and so he wrote literature. But a screen writer - like Alan Smithee - writes movie scripts. And except for scriptwriters, few people would say movie scripts are literature.

And Bob wrote songs, not poetry. So what Bob wrote must needs have the music as well as the words. Real poets don't need musical instruments. Their words themselves are the music.

With all due respect, them's is funny sentiments (as Woody might have said). Consider this verse:

Hear this, all you people.

Listen, all who live in this world,

Both low and high, rich and poor alike.

My mouth will speak words of wisdom;

The meditation of my heart will give you understanding.

I will turn my ear to a proverb;

With the harp I will expound my riddle.

Only would the most curmudgeonly of curmudgeons say this was not poetry. It is, in fact, taken from a quite famous book of poems (can't remember it's name right now).

But notice the last sentence. It mentions that "with the harp" the poet will expound his riddle.

In fact, early poetry was sung. Of course, today that singing might be dismissed as mere (ptui) recitation. But for the Romans, Greeks, and into the Middle Ages, reciting poetry without music was the exception not the rule.

And let's also remember that in recent times it's been common to put the words of famous poets to music. Galt MacDermot - the composer of the music for the Broadway hit Hair - used part of a speech from Hamlet for the song "What a Piece of Work is Man". It's one of the best songs in the show, but does that mean Will's plays are no longer literature?

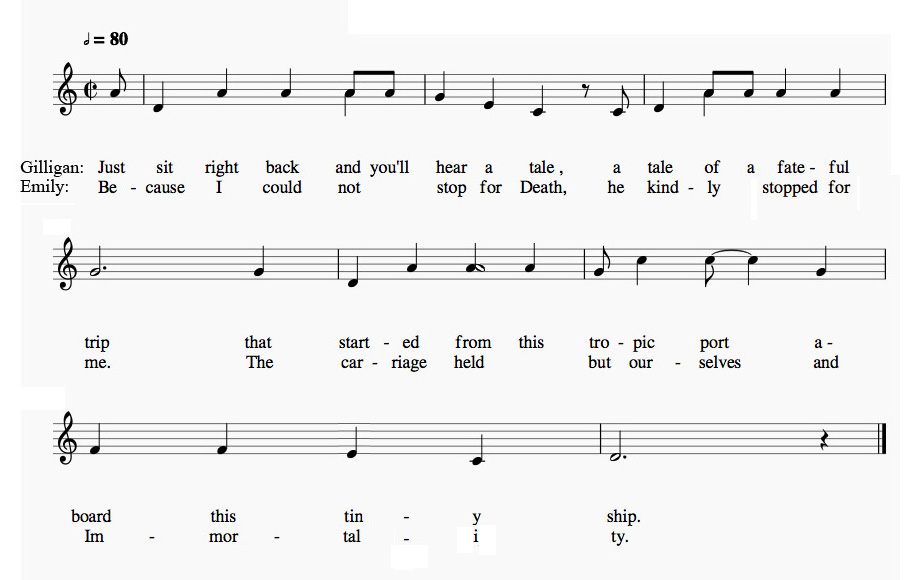

And consider the verses of Emily Dickinson. Many of them have been set to music, and as you can see if you click on the image at right, most of them can be sung to the tune of "The Ballad of Gilligan's Island". And yet no one seems to think that all of a sudden Emily's poetry is no longer poetry.

On the other hand, no one is claiming that the poetry from the lyrics of songs are always good poetry. For instance, here's some lyrics from a surprisingly popular tune.

Ba, da, ba, da, da, da, da

Ba, da, da, da, da, da.

Certainly we don't see that song getting anyone a Nobel.

But now let's look at the lyrics of some of Bob's songs.

And take me disappearing through the smoke rings of my mind

Down the foggy ruins of time, far past the frozen leaves

The haunted, frightened trees, out to the windy beach

Far from the twisted reach of crazy sorrow.

And this:

How many roads must a man walk down

Before you call him a man?

Yes, and how many seas must a white dove sail

Before she sleeps in the sand?

And even:

Well, they'll stone you and say that it's the end.

Then they'll stone you and then they'll come back again.

They'll stone you when you're riding in your car.

They'll stone you when you're playing your guitar.

Well, maybe this last example isn't the best.

Nevertheless, from these lyrics we can glean at least part of the reason for the wide appeal of Bob's songs. And that is that anyone, regardless of political persuasion and in whatever era they live, can belt out these words with gusto. We see then that Bob's songs, while appealing to the generic rebel that everyone imagines is within, nevertheless do not really deliver any specific political message or advocate any particular idealism.

Well, we have to qualify the statements as did the Captain of the Pinafore. Some of Bob's songs do target definite philosophies. These songs, though, are often the most dated. Take Bob's "Talking John Birch Society Blues":

Well, I quit my job so I could work alone

Then I changed my name to Sherlock Holmes

Followed some clues from my detective bag

And discovered they was red stripes on the American flag.

Although the organization is still around, few people remember the John Birch Society. Its main philosophy was (and is) to staunchly oppose leftists politics in general, and communism in particular. Of course in a world where even communists don't like communism, and liberals deny they're liberals, most people will miss the point of the jokes. C'est, as Americans say, la vie.

As to what is Bob's personal philosophy, he's always been a pretty private person. Some commentators have even referred to him as a recluse. His private nature and his avoidance of overt politicization makes Bob an easy target as one who eschews taking a stand on important issues. Actually he has lent his talents and support to a number of worthy causes, and once he said that although he supported a particular cause, he wasn't going just hold up a sign to turn it into personal photo-op.

But in any case, Bob did not win a Nobel Prize in Singing of which, thankfully, there is none. Bob won the Nobel Prize in Literature - and we may quote - "for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition."

Now it's really no surprise that Bob didn't attend the ceremony - which isn't required of the winners. But what is required is that within six months, the laureate must deliver a Nobel lecture. They don't have to give a talk themselves, but the Nobel Committee has to have it delivered. So with a few days to spare, Bob handed over his lecture which had been recorded on tape.

It's actually a good speech. Bob's voice is well-modulated, soft-spoken, and articulate, nothing at all like that of the Bob Dylan satirists. He talks about the influences on his music, and the lecture comes off as a performance of poetry. And yes, there's a nice piano accompaniment in the background which was played by Alan Pasqua, Professor of Music at USC's Thorton School of Music. Alan, in his younger days, had toured with Bob.

And if Bob hadn't delivered the lecture? Well, he would have in effect turned down the prize - and the $900,000 that went with it.

Some people have found fault with what seemed Bob's lackadaisical approach to accepting the highest literary distinction in the world. He didn't even say yea or nay to the Nobel Committee for two weeks. But at least Bob didn't take a high-hatted flip-flop like the French author, playwright, and philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre.

In 1964, Jean-Paul had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for "his work which, rich in ideas and filled with the spirit of freedom and the quest for truth, has exerted a far-reaching influence on our age". But because he refused to be part of the establishment, Jean-Paul turned the prize down. Besides, he said, he never accepted awards.

Now Jean-Paul didn't reap as munificent rewards from literature as Bob did. Oh, Jean-Paul did OK and wrote a number of plays that remain popular enough ("No Exit" is still widely performed). But at times he was strapped for cash. I mean, there are only so many people willing to listen to lectures on existentialism. So ten years after Jean-Paul turned down the prize, someone discretely approached the Nobel Committee asking if Jean-Paul might possibly be given the money for the prize. Jean-Paul didn't want the prize, thank you. Just the money.

Jean-Paul Sartre

Not the Prize, Just the Money

That Jean Paul would secretly ask for the money of a prize he had publicly rejected sounds like a snit so typical of des déchets you'll read on the Fount of All Knowledge. But the source of the story is a good one. It comes from none other than, Lars Gyllensten, who was the Nobel Committee member in charge of the Literature Prize. So that some representative acting on Jean-Paul's behalf asked for the dough can't be denied.

But in the end it didn't matter. The money had been returned to the Nobel fund for future prizes.

Dommage, Jean-Paul, aucune acceptation, aucun argent.

References

"Bob Dylan: An Intimate Biography", Anthony Scaduto, Grosset and Dunlap, New York, New York, 1971.

"Woody Guthrie", Pete Seeger (host), Rainbow Quest, 1966.

Woody Guthrie: A Life, Joe Klein, Knopf, 1980.

Down the Highway: The Life of Bob Dylan, Howard Sounes, Grove Press, 2001.

Rainbow Quest, Pete Seeger (host), Internet Movie Data Base, 1965 - 1966. Rainbow Quest was a television show hosted by Pete and is probably one of the best folk music programs put to tape. Although Pete did have some songs about folks singers where he sang the songs (like the ones about Woody and Leadbelly), most of the shows featured the actual performers. Among Pete's guests on the various episodes were Ramblin' Jack Elliott, Tom Paxton, the Clancy Brothers with Tommy Makem, Martha Schlamme, Jean Ritchie, Hedy West, Mississippi John Hurt, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Len Chandler, Donovan, Theodore Bikel, Judy, Collins, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, and some guy named Johnny Cash who was with a young lady named June Carter.

Ramblin' Man: The Life and Times of Woody Guthrie, Ed Cray. Norton, 2004

"Back Where I Came From", Clifton Fadiman (host), Columbia Broadcasting System, August 19, 1940.

"Bob Dylan Visits Woody Guthrie", Caspar Llewellyn Smith, The Guardian, June 15, 2011.

"Bob Dylan Delivers His Nobel Prize Lecture Just in Time", Ben Sisario, The New York Times, June 6, 2017.

"Ramblin' Jack Elliott On The Debts Between Him and Bob Dylan", Brad Wheeler, The Globe and Mail, October 25, 2016, (Updated: March 24, 2017.

"Timeline of Woody Guthrie", Woody Guthrie and the Archive of American Folk Song: Correspondence, 1940 to 1950, Library of Congress.

"Is Bob Dylan a Phony?", Sean Wilentz, Daily Beast, April 30, 2010.

"Woody, Bob and Me," John May, The Telegraph, February 19, 2005.

"Bob Dylan’s Nobel Prize for Literature is Deserved and Overdue", David Lister, The Independent, October 13, 2016.

"Bob Dylan Doesn't Deserve the Nobel Prize In Literature and He Shouldn't Want It", The Stranger, October 13, 2016.

Legends of Folks: Live From the World Theater, Ramblin' Jack Elliott (performer), Spider John Koerner (performer), U. Utah Phillips (performer), Red House Records, 1990.

Minnen, bara minnen, Lars Gyllensten, Bonnier 2000.

Nobel Lecture, Bob Dylan, Nobel Prize, June 5, 2017.

"Announcement: The 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature", Nobel Prize, October 13, 2016.

"Announcement: The 1964 Nobel Prize in Literature", Nobel Prize, October 22, 1964.

"The Nobel Prize in Literature 1966", Nobel Prize.

"Alan Pasqua Featured in Bob Dylan's Nobel Prize Lecture", Thorton School of Music, University of Southern California.

"Flashback: Joan Baez Pleads With Bob Dylan Via Song", Andy Greene, Rolling Stone, March 10, 2016.