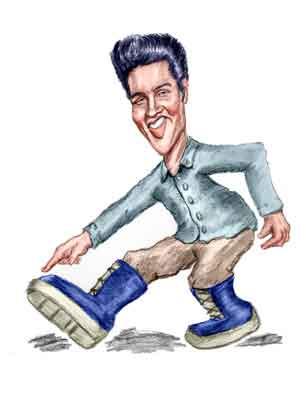

The great composer, guitarist, and singer

Carl Perkins

would never have thought ...

...that he and his BLUE SUEDE SHOES could also help demonstrate the advantages of scaleable vector graphics. But if you twiddle with the numbers above, you'll see the changes that can be effected with a single SVG image.

The point is that the various views formed by changing the numbers are from only a single image - NOT from multiple images of varying resolution and size. There is a caution in that altering the numbers can make drastic changes in the picture and if you end up seeing nothing, you've probably pushed the image out of the range of the window. Click "Restore Defauts" and the picture should reappear.

There's plenty of information out there detailing how the ViewPort and ViewBox work, but here we'll give a quick overview.

But first a bit about Carl.

Carl Lee Perkins was born April 9, 1932 in Tiptonville, Tennessee. This is way up in the northwest corner of the state near where Tennessee, Arkansas, Kentucky, and Missouri bunch close together. So Tiptonville is a little south from where the Mississippi River makes it's famous ox-bow bend where a bit of Kentucky is isolated from the rest of the state and you have Missouri to the north, east, and west, and Tennessee to the South. The summer climate is hot and steamy.

Carl's parents, Fonnie "Buck" Perkins and Mary Louise Brantley, were sharecroppers living on a 400 acre plantation. Buck and Louise were poor even by the standards of the time and place. Naturally Carl went to the fields at an early age picking cotton alongside of his parents and brothers. Despite their privations - eventually Buck's health deteriorated to where he couldn't work - Carl spoke fondly of his parents and family.

But life was not all work and no play. The kids could go to the movies on Saturday and at night the family would listen to the Grand Old Opry on an old battery powered radio (their house didn't have electricity). Their dad was a big fan of country music and Carl swore he would one day appear on the Opry.

Carl's first guitar was purchased for three dollars and a chicken from a black neighbor named John Westbrook. Carl's best friend, Charlie, was also black, and Charlie's family lived and worked on the same plantation as the Perkins. While most everyone else told Carl he should learn to drive a truck and a tractor, Charlie said that he thought Carl would make it as musician.

By his early teens Carl's singing and guitar playing had gotten quite good and he won an amateur talent contest singing his own composition, "Movie Magg". He also began playing on a local radio station, WDXT, which sometimes featured local talent. The stations rarely paid the performers, but the shows gave musicians publicity, and they could legitimately claim they were "heard on WDXT".

To go further in his ambitions, Carl realized he needed a band. At first his brother, Jay, wasn't too interested in music, but Carl persuaded him to learn rhythm guitar. His younger brother Clayton took the stand-up "slap" bass, and the boys began playing for local functions. They branched out to playing in the bars - called "honky tonks" - where they actually got paid.

After World War II, the family relocated to Bemis, a small town just south of the "big city" of Jackson. The brothers split their time working in the cotton mills during the day and playing the "tonks" at night. In 1953, Carl married Valda Crider. Of course, Valda not only knew of Carl's musical ambitions, she actively encouraged them. So it's not too much of a surprise that the marriage lasted.

Of course technology was changing and with it the music. If you were playing in honky-tonks, non-amplified instruments just couldn't be heard. Some musicians stuck with acoustical instruments that had been "miked", but Carl went electric. He changed guitars frequently, and these were no minor expense. In the 1950's a Gibson Les Paul could run $800.

The next step for a serious musician was to cut some records. The old 10-inch 78's were on their way out and the 7-inch 45's were what the kids were buying. Carl knew that there was a company called Sun Records down in Memphis. The owner of Sun, Sam Phillips, was a man open to new talent. That is, if they were good, and he thought they would be successful. So Carl and his brothers made the 80 mile trek to Memphis.

Sam was not particularly impressed with the Perkins brothers. There just wasn't anything distinctive about the group or the sound. The previous year he had recorded a young truck driver (!) singing "That's All Right", a composition by black bluesman Arthur "Big Boy" Crudup. On the flip side was "Blue Moon of Kentucky", originally a staid slow pace waltz written by Bill Monroe.

But Elvis had jazzed the tune up considerably, producing what Carl himself said was the first true example of "rockabilly". The song took off, and Elvis quickly become Sam's #1 artist. In fact, he was so good that RCA - with a wee bit of help from Elvis's astute manager "Colonel" Tom Parker - quickly stepped in and bought out the contract.

Elvis

Before

After

So despite Sam's reservations about Carl's music, he was now looking for new artists. He was also a believer in giving people a chance, and he cut two sides for Carl.

Unfortunately, the songs didn't make much of a splash. But while at the studio, Carl met another of Sam's rising stars, a young man named John Cash who Sam had dubbed "Johnny" for the record labels. The two men hit it off immediately. John was also starting a tour and needed a warm-up band. So the Carl Perkins Trio - even though once they added drummer W. S. "Fluke" Holland it was a quartet - was signed up.

John had actually been lucky to wrangle an audition from Sam since he had trouble getting past Sam's secretary, Marion Keisker. She - Marion is the correct spelling - always tried to keep her boss shielded from the crowd of would-be musicians that were continually pounding on his door.

But eventually John made such a nuisance of himself that Sam agreed to hear him. He liked the newcomer's voice - which was a distinctive basso profundo - and asked John to come back with his group.

John returned with his bass player Marshall Grant and guitarist Luther Perkins (no relation to Carl). At that time neither Marshall nor Luther were polished performers (which is putting it politely). But despite (or because of) these limitations, together with John's rhythm guitar (which even John admitted was rudimentary), they were able to produce a distinctive boom-chicka-boom sound that Sam recognized had commercial potential. And we know both Marshall and Luther achieved considerable proficiency.

Johnny Cash

He and Carl hit it off.

Carl and John's first show together was at a theater in Parkin, Arkansas, about thirty miles west and a bit north across the Mississippi from Memphis. It was a pretty rudimentary venue, and the men's room was however you could manage going out the back door and into the alley.

In 1955 Sam arranged a tour which in hindsight was a historical event. There were three bands on the ticket: Carl, John, and ... Elvis. Yep, although they were often playing at high school auditoriums, Carl Perkins, Johnny Cash, and Elvis Presley performed on the same shows.

In Carl's performances he would often play his own songs. Over the years, his compositions included "All Mama's Children", "Because You're Mine", "Boppin' the Blues", "Dixie Fried", "Matchbox", and "Let the Jukebox Keep on Playin'". Later Carl wrote "Daddy Sang Bass" which became a classic after Johnny Cash and June Carter began featuring it in their concerts.

Toward the end of the year and with the tours over, Carl came to the Sun Studios with a new composition. The opening lines were:

One for the money.

Two for the show.

Three to get ready.

Now go, cat, go!

Huh? "Cat?" That was what the hipsters called each other. The bearded bohemians, the beatniks.

This was Country music?

The Cats

"Blue Suede Shoes" was certainly a departure from earlier songs. Elvis's recordings of "That's All Right" and "Blue Moon of Kentucky" had at least some connection with the hill culture and fit in the mold of rockabilly. But although "Blue Suede Shoes" was first labeled "Country" it had clearly crossed the line to a new genre of music that was even then being dubbed rock and roll.

The song was released on New Year's Day, 1956. From the reception at the local stations, Sam anticipated a good nationwide sale. The song quickly caught the attention of the Billboard editors who, although classifying it as Country, noted its rhythm and blues style backing. Reviewers rated it 76 out of 100.

Within three months "Blue Suede Shoes" had moved to the Billboard Top 100 and in a week it was on the Rhythm and Blues charts. The song kept moving up and crossing over and it ultimately peaked at #2 as a pop tune.

Carl found himself being mentioned in the national newspapers, and the group began hitting the radio and television programs. In March he appeared on the Ozark Jubilee which at the time was bigger than the Grand Old Opry.

But then something really unexpected happened. Carl and the group got an invitation to appear - not on the Louisiana Hayride, not on WLS Barn Dance, and not even on the Grand Old Opry. They were invited to appear on Perry Como's Kraft Music Hall.

Hank Williams

It seems odd that the host of America's #1 squeaky-clean variety show and which was broadcast from New York City would ask for someone from the sticks to play raucous rock and roll. But Perry was open to all types of music and had once even invited Hank Williams on the show. Hank sang his song "Hey, Good Lookin'" which was quickly adopted by Perry who sang it as his opening number the next week. The line between Country and Popular Music was fast blurring, and Carl and the group appeared on Perry's show on May 26 and sang "Blue Suede Shoes".

But it was a delayed appearance. The band was supposed to have performed on March 24. But on the 21st they had been playing in Norfolk, Virginia, and immediately afterwards Carl, Jay, Clayton, and Fluke, along with Memphis disc jockey Dick "Little Richard" Stuart, loaded up their car and began driving non-stop through the night and on toward New York.

Exactly what happened isn't clear, but in the early morning they had nearly reached Dover, Delaware, along Highway 13. Fluke had started out driving but he began to get sleepy and pulled into a gas station. Dick volunteered to drive so Fluke could take a nap. Fluke said fine. They got back in the car and Fluke lay back to get some shuteye.

The next thing he knew, he was sitting in the middle of the highway. He looked up and saw the car had been demolished. The usual account is they had rear-ended a farmer's truck and landed in a ditch with about a foot of water.

Fluke quickly located Jay, Clayton, and Dick. All were alive. But Fluke couldn't find Carl.

Then he looked in the wreck and saw the back seat had jarred loose. He pulled it back and found Carl was laying face down in the water. He hauled him out of the car, and Carl began to breathe.

The truck driver later died and except for Fluke all the others were seriously injured. Jay was severely lacerated along his legs, and Clayton, although he didn't realize it and seemed relatively unhurt, had broken his neck. He did survive, although his injuries are believed to have contributed to his death a few years later.

Carl had broken his collarbone, had been cut almost everywhere, and had a concussion. But in the hospital he soon recovered consciousness and was even able to watch Elvis on TV. When Elvis and his group heard of the accident, they sent their wishes for a speedy recovery.

Carl was released on the understanding he was to be readmitted to a hospital in Jackson. To [heck] with that he thought. He had a bed at home and he could manage there just as well.

The car accident and the enforced time off are sometimes cited as what prevented Carl from being as big a star as Elvis. However, Carl was actually back on the road pretty soon (too soon probably). He rescheduled his appearance on the Perry Como Show and appeared in May, a delay of only two months. By that time Blue Suede Shoes had already sold over 500,000 copies and so had "gone Gold". It eventually became Sun Records' first million seller.

Well, if it wasn't the accident that kept Carl from becoming as big a star as Elvis, what did?

One word.

Elvis.

Elvis had become a phenomenon. His mellow and (yes) pleasant voice was immediately recognizable. If you heard him on the radio, you didn't have to ask.

And in live performances Elvis was sui generis. "Vigorous" doesn't do justice to his early performances. He would gyrate across the platform, backwards, forward, sideways, all the time with his, well, "distinctive" hip swiveling, even though in some cases he seemed to be indulging in a bit of self-parody.

And there was simply the fact that he had the looks of the teen idol. Carl acknowledged Elvis's appeal to the young ladies and said that he and the other rockabilly singers looked more like Mr. Ed.1

Footnote

Mr. Ed was a television program about an architect named Wilbur Post (played by Alan Young) who lived on a farm and who owned a talking horse named Mr. Ed. For some reason the show proved popular and aired from 1958 to 1966.

Although you may read how rock-and-roll was considered anti-American and after the payola scandal it was hounded off the airways, Elvis quickly reached the mainstream. In 1956, only two years after his first Sun Record was released, he appeared in his hometown of Tupelo, Mississippi. After giving a typical frenzied Elvisian performance, the Mississippi governor - yes, the governor - appeared on stage to award Elvis a special citation.

It was toward the end of the year that RCA released Elvis's recording of "Blue Suede Shoes". Normally releasing a cover record while the original was still selling strong made no business sense. But remember, this was Elvis. Besides he wanted to record the song as much as a tribute to Carl as anything. The release was certainly to Carl's benefit since although Elvis's record was issued by RCA, Carl would still get royalties as the composer.

On the other hand, Elvis's "Blue Suede Shoes" pushed Carl's own version from the charts and to a great deal out of the American collective consciousness. A lot of kids who were playing Elvis's version had never heard of Carl Perkins.

The 45's had two sides, of course, and on the flip side of "Blue Suede Shoes" Carl had recorded another of his songs. That was "Honey Don't" and it was a little more straight forward in content. A fellow is bemoaning the fickleness of his girlfriend who sometimes says she will when she won't and tells him she does when she don't.

"Honey Don't" is arguably Carl's most popular song. Certainly it's proven popular with other singers. Over the years it's been covered by Wanda Jackson, Shakin' Stevens and The Sunsets, Harry Fontana and The Tennessee Tone Boys, Billy Field, Caballero Reynaldo, Skitzo, Tony Vincent, Kendy Toms and The Red Boots, The Country Gentlemen, Maines Brothers Band, Johnny Rivers, Lee Sims and The Platte River Band, Top Cats, Andy Lee Lang, Ian B. MacLeod, The Stroller, Blinkit and The Mighty Blue Cloud Horn Section, Lee Rocker, T. Rex, The Black Barons, 18 Wheelers, The Coverbeats, Orion, The Rockabillys, Shaking Stevens and Fumble, Rockin' Lord Lee and The Outlaws, Joe Walsh, Steve Earle, Ronnie Hawkins and The Hawks, Warren Phillips and The Rockets, Mac Curtis, Eugene Chadbourne, Ben Folds, Brandy Roberts, Vince Taylor, The Bobby Clark's Noise, Glen Glenn, Stan Perkins, Ian B. MacLeod, Rock Hotel, Memphis Rockabilly, Carlinhos Borba Gato, Tyrone Schmidling, Homer and The Dont's, Srta Luck and Los Delux, Evan Johns, The Rocky Road Ramblers, and The Boppers.

The Fab Four

But the version that introduced Carl to the 60's rock fans was by - who else? - the Fab Four. True, it wasn't a chart buster - in 1964 it reached #68 on Billboard as the single "4 by the Beatles" (with four songs, two on a side2). But the song was popular in concerts as it was one of the few songs where Ringo3, a big country and western fan, took the lead vocals. Years later when Carl was appearing in London, Ringo sat in on the drums and gave one of the song's better renditions.

Footnote

These "double singles" did not prove commercially successful. Teenagers of the 50's and 60's preferred being able to select one song at a time. And they didn't have to get up and change the record after each tune. The record players of the time let you stack the records on a spindle in the middle of the turntable. After each record was played, the next would drop down and the arm would automatically reposition itself and the next platter would play. Then once all the records were over, you could take the stack, turn it over, and play the reverse sides. These features were available on all record players of the 1950's whether they were the small players designed for '45 discs or the 33⅓ long play albums.

But now a bit more about the scaleable vector graphics.

At this point the reader is surely wondering about the image of Carl and how only one picture can be displayed in so many ways on a single web page. In fact, the same image can be displayed at multiple places at multiple sizes and in multiple ways on multiple web pages. How is this possible?

Well, it's very simple really.

As explained in some detail in the earlier essay on scaleable vector graphics - SVG for short - the picture of Carl used here employs in-line vector image code. But it's been adapted using Javascript programming so the code that produces the image is kept in only one separate file. That way it can be accessed by any webpage and so it can be displayed as often as desired. On the other hand by using in-line code with Javascript, there are no external URL references needed as for the more common .svg files.

And the big advantage of a Javascript SVG image is that once created, the image can be resized without loss of resolution and cropped as you like - all without without explicitly rewriting the SVG code. So why not always use SVG and not JPEG's, GIF's, or PNG's?

Well, one disadvantage is that many SVG files tend grow rapidly in size as the complexity of the image increases. The picture of Carl takes up about 220 kilobytes of memory while a JPEG of the first view might only take 20 kilobytes. Certainly 220 kilobytes is larger than many web images, but it's considerably smaller than higher resolution pictures that could be used for printing images of poster size.

But if you take the SVG image and add additional features - like highlights - are added, the size of the file grows considerably. Even small highlights can bump the memory to the megabyte range. In that case using traditional images is more memory economical.

Another problem using the Javascript approach is in the "Reading View" modes on some small devices. A reading view is a format to make the text more legible. But in-line SVG images - even if imported from a separate file - might disappear.4

Footnote

To avoid losing the image, it can be stored as the more typical .svg image. Usually these can be formatted and displayed like other image files.

Still whether you use the file from a direct inline code, a Javascript function, or an external .svg file, the real advantage of scaleable vector graphics is that the image can be displayed enlarged, cropped, and zoomed versions without loss of resolution. However, exactly how to crop and zoom the image often confuses those beginning to toy with SVG images.

As should be clear from the picture of Carl at the top of the page is that the main parameters for editing an SVG image for display are the area of the computer window where the image is to be displayed - called the ViewPort - and the part of the image to be displayed - called the ViewBox. Changing these parameters permits the image to be cropped, zoomed in and out, and moved back and forth and up and down. In principle, any values for the parameters are permitted but negative numbers for widths and heights will produce an error - most likely a blank picture.

If you select a ViewPort set to Width="100" and "Height="100", this means there will be a 100 pixel X 100 pixel square reserved for the picture. Now for web pages if there are no units you can assume they are pixels.

But you can - as we do above - use other units including relative units. The ViewPort of our picture of Carl is in percents. So entering 50% in the first space means the image will be 50% of the width of the computer window. Remember this is the currently open window and is not necessarily the whole computer screen. (Note: Due to the manner in which the SVG image of Carl was created, the height is predetermined by the width and so is disabled and greyed out. But in some SVG images, the width and height can be set independently.)

So we see the ViewPort is easy to understand. It's just a part of the window reserved for the picture. But what causes many beginners - and some old hands - to tear their hair and bewail their fate is understanding and handling the ViewBox.

Remember the ViewBox determines which part of the picture is viewed, how much it's zoomed in and out, and how much it's shifted left and right and up and down. To do this, the ViewBox treats the image like it is drawn on graph. That is the picture is plotted out on coordinates like you did in middle school geometry class. But for some reason, developers of vector graphics decided to do things a bit differently.

Like normal Cartesian coordinates, the X coordinate's of the ViewBox - which are on the horizontal axis - increase from left to right. However, the Y coordinates - on the vertical axis - increase as you move down. Who knows why this is, but that's the way they made it.

Another part of the problem is not just that the coordinate system is upside down, but that the parameters seem to be arbitrary units. But although the units are sometimes referred to as "user-supplied", they are actually good old straight-forward pixels. When an SVG image is created, the default units are pixels and there's really no reason to change them. Just think "pixels" and you'll be all right.

But perhaps the greatest point of confusion with the ViewBox arises because the numbers in the ViewBox are not the same things. The first two numbers are the X and Y coordinates for the origin of the image. A full SVG image is usually defined with the (X, Y) origin at (0,0) in the upper left hand corner of the ViewPort.

But the next two numbers in the ViewBox are NOT the X and Y coordinates at the end points of the image. In fact, they're not coordinates at all. Instead they are the width and height of the part of the image to be displayed.

The default ViewBox of the image of Carl is "0 0 1250 1450". So the whole image takes up a rectangle that's 1250 pixels wide and 1450 pixels high. The origin is (0, 0) in pixels and is set at the upper left hand corner of the area of the window reserved by the ViewPort.

But instead of using the default ViewBox of "0 0 1250 1450" which displays the whole image, let's first set the origin at (X,Y) = (125, -50). Yes, the origin's numbers can be negative. They can be also be larger than the maximum value of the default values.

Now set the width and height of the ViewBox to be 750 and 450 respectively. So the right edge of the ViewBox is now 125 + 750 = 875 pixels from the original origin of (0,0). The lower edge is -50 + 450 = 400 pixels from the original origin. Therefore with a ViewBox="125 -50 750 450" we "carve" out the rectangle shown below in pink.

Carl and the ViewBox

ViewBox="125 -50 750 450"

So if you plug these numbers for the image of Carl at the top of the page (which has a 50% ViewPort), you'll get:

ViewPort Width: 50%

ViewBox="125 -50 750 450"

Now you can enlarge the image by simply setting the width to a higher value, say to 90%. Hey, presto!, you get a zoomed in Carl:

ViewPort Width: 90%

ViewBox="125 -50 750 450"

Now although there are separate Translate parameters for SVG images for shifting the picture left and right and up and down, but these aren't usually needed. Instead you can just decrease the X coordinate of the ViewBox and Carl moves to the right:

ViewPort Width: 90%

ViewBox="-150 -50 750 450"

Increase it and Carl moves to the left:

ViewPort Width: 90%

ViewBox="250 -50 750 450"

Ramp up the Y coordinate and Carl moves up:

ViewPort Width: 90%

ViewBox="-50 100 750 450"

Knock it down and Carl drops:

ViewPort Width: 90%

ViewBox="-50 -200 750 450"

And you can move him even further down:

ViewPort Width: 90%

ViewBox="-50 -320 750 450"

And if you want to see Carl from afar, just change the numbers again:

ViewPort Width: 50%

ViewBox="-2000 -1000 5000 3000"

So in principle any part of the image can be displayed as large as you like. And with the settings:

| ViewPort: | 90% | ||||

| ViewBox: | 255 | 1200 | 475 | 250 |

...you can zoom in on what started it all.

ViewPort Width: 90%

ViewBox="255 1200 475 250"

It may seem odd given Elvis's increasing deification, but from 1960 to 1965, Carl was mentioned in newspapers and magazines more than Elvis. This, though, was the time when Elvis had seen a slump in his career and people were wondering if he was going to fade from the American scene. Carl, on the other hand, was being cited by the new wave of singers, particularly those of the English Invasion, as a major influence.

But as the Swinging Sixties moved on, Elvis began to change from the teen-idol rock and roller to the Vegas headliner that Mom and Dad went to see. By the early 1970's Elvis had become newsworthy and this reached a high point on August 16, 1977. After that his fame rose exponentially and the rise has never abated.

Carl had also seen an increase in his fame even though he was no longer leading his own band. Instead he was touring as the lead guitarist for Johnny Cash who had become a megastar. Marshal Grant was still playing bass and it was none other than Fluke Holland on drums (and who was also John's road manager). This was also the band that appeared with John at his famous performance at Folsom Prison as well as at San Quentin where John first sang "A Boy Named Sue".

After performing with John for over ten years, Carl again took out on his own. His own kids were now grown and they took after their dad and joined him on the tours. His position as one of the founders of rock was now firmly recognized and he was sought, not just for performances - including one at London's Royal Albert Hall - but for interviews. Once he appeared on a famous talk show and Carl's easy going and humble nature was evident. The interview could have been even more informative except that the host tended to talk so much his guests could hardly get a word in edgewise.

In addition to playing guitar with John over the years Carl appeared in shows and festivals alongside other megastars like Roy Orbison, Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr, George Harrison, Jose Feliciano, Muddy Waters, Jerry Lee Lewis, Buddy Holly, and yes, remember Carl had even toured with Elvis. Carl kept performing almost to the end which came sadly on January 19, 1998 when he was only 65.

References and Further Reading

Go Cat, Go! The Life and Times of Carl Perkins, The King of Rockabilly, Carl Perkins and David McGee, Hyperion, 1996.

"Carl Lee Perkins", Stacy Harris, Tennessee Encyclopedia.

The Encyclopedia of Popular Music, 10 Volumes, Colin Larkin, Oxford University Press, 2006.

"Carl Perkins", History of Rock.

"Carl Perkins Interview", Tom Snyder (Host), The Late Late Show, 1997.

"The Lowdown" Minneapolis Spokesman, May 11, 1956, Page 6.

"Programs and Highlights for Saturday, March 24", [Washington, D. C.] Evening Star, March 18, 1956, Page E-9.

"Rockabilly", Encyclopedia Britannica.

"Carl Perkins' Guitars and Amps", Vince Gordon, The Rockabilly Guitar Page

"Carl Perkin, Elvis Presley", Ngram Viewer, Google Books.

"Honey Don't", Second Hand Songs.

"All US Top 40 Singles for 1965", Top 40 Weekly.

"Carl Perkins Car Crash", Wanda Feathers, Rockabilly Take Note Archives.

The Perry Como Show, May 26, 1956, NBC, Internet Movie Data Base.

"Carl Perkins, Rock 'n' Roll Pioneer", BBC, January 19, 1998.

"Blue Suede Shoes: Chronology of a Hit", The Blue Suede Shoes Story, Rock-a-Billy Hall of Fame.

"Blue Suede Shoes: From Perkins to Presley", Luke Saunders, Happy, September 15, 2021.

"Carl Perkins's Concert History", Concert Archives.

"Carl Perkins", Find-a-Grave, December 31, 2000.

"Fonnie 'Buck' Perkins", Find-a-Grave, July 30, 2014.

"Mary Louise Brantley Perkins", Find-a-Grave, January 26, 2008.

"W. S. 'Fluke' Holland", Find-a-Grave, David Mayo, September 23, 2020.