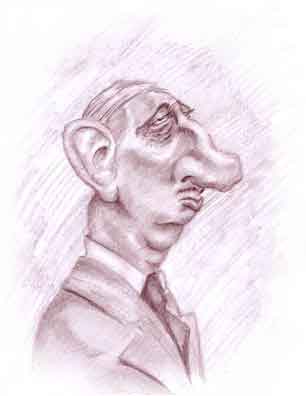

Charles De Gaulle

Le Grand Charlot

Charles De Gaulle

Et nous entendons GRAND!

(Et pas seulement le nez!)

In May of 1940 the War had just begun - no, no, we're not misdating Johnny Horton's hit song, "Sink the Bismark". But it was the following month that France capitulated to - ah, we mean they negotiated a cease fire with - Germany. Suddenly all those horrible jokes that Americans like to tell about France suddenly looked like they were coming true.

It all started the previous September when British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain told the grandson of the former Maria Shicklegruber that if he invaded Poland, then the English would declare war. Well, he did and they did, and France, being allied with England, also declared war on Germany.

The trouble was Germany had been gearing up for war for the past six years. Now they blitzed not only into Poland but also into Denmark, Norway, Belgium, Luxembourg, Holland, and, yes, France. On June 20, France surrendered.

One of the French soldiers was particularly irritated. That was Brigadier General Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle, who also held the fancy pants title of Undersecretary of State for National Defense and War. Charles had been born in 1890 in Lille and breaking away from his family tradition - his dad was a college professor - had decided on a military career. He attended the Military Academy of Saint-Cyr and saw action and had been taken prisoner of war in World War I.

After the War Charles continued his military education at the École Supérieure de Guerre. This was the French equivalent of America's War College and was where promising officers went to learn the finer points of strategy and tactics.

Charles did well and afterwards became an instructor at the École. There he wrote some books and gained a reputation as a military theoretician and came to the attention of the Maréchal Phillipe Pétain, the head of France's military and the big hero of the war. Charles was appointed to the Supreme War Council, which was an international group of military leaders created during the War and which was thrashing out the issues left over after the Amistice.

Charles, like others in Europe, watched the rise of Hitler with increasing concern and when the Germans annexed Austria and took over Czechoslovakia, the concern rose to alarm. And so things were when Germany invaded Poland.

Charles had been telling his superiors for years that mobility had become the key to military success. When the Second World War began, Charles was a colonel but was promoted to brigadier general of the 4th Armored Division. But the other French military leaders kept with the old idea of static fortifications along the old Maginot Line and mobile forces were considered unimportant. Alas, the Germans soon proved Charles was right, and so France surrendered.

Some of the French soldiers were taken as prisoners of war and released within a year. But others were kept in Germany officially as "workers". Of course they were really hostages to make sure the French government gave Germany the treaty they wanted. Nominally paid a wage, they were actually slaves and many never returned to France.

To give the treaty some credibility with the people, the President of France, Albert Lebrun, turned the negotiations over to Philippe, whom the people held in high regard. Albert also informed the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill (who had replaced Neville), they were going to throw in the towel. Winston tried to argue Albert out of it but as far as Albert was concerned Enland had started the whole bloody mess in the first place. Winston then grudgingly admitted France had the right to decide for themselves what to do.

The Germans demanded - we'll still call it "negotiated" - terms with the French. The north half of France (which included Gay Paree) was occupied by Germany as was the 50 miles or so of land lining the west coast. Paris, of course, was a great place for soldierly R and R as well the beginning of a convenient corridor to the English Channel if you ever want to invade Britain.

The southern half, though, would be a - quote - "free country" - unquote - with the government set up in the town of Vichy. Now called Vichy France by historians, the Prime Minister designate was none other than Philippe who was also granted absolute powers and would operate independently of Germany.

Ouais c'est ça!

The trouble was Charles was still causing trouble. Rather than accepting what the government agreed to - as all good government bureaucrats should - why, he had skinned out of France and crossed the Channel to England! Now he had set himself up as the head of what he was calling "Free France" was urging all Frenchmen to fight against the Germans!

Treason! Charles was tried in absentia and condemned to death.

Anyone with a general knowledge of the era knows Charles had a bit of a strained relationship with Winston and with US President Franklin Roosevelt. What isn't appreciated is that the fractiousness got to the point that a little shove was close to derailing the whole shebang.

You see, Franklin and Winston would have been perfectly willing for the Pétain government of Vichy to be the official French government. As we mentioned, when France capitulated this was done with the acquiescence of Britain. In fact, Winston had even told Phillipe that he would not fault France for having to surrender.

Winston and Franklin figured if Philippe realized the Germans would lose, he would be happy to secretly pave the way for an Allied invasion. That way once the Germans had left an area, you had a functioning government already in place. Since Philippe had been granted dictatorial powers, then what he said would go as long as he did what the British and Americans wanted.

But Charles put them in a tough spot. He had been high up in the government but not really high enough to claim he was in charge. But that's what he was saying and he was now calling for all Frenchmen to fight the Germans, even if it meant to become guerilla fighters. So Philippe got locked into a position where he had to fight the French underground fighters, called the Le Résis (Resistance in English) who were damaging government property, keeping tabs on German military movements, printing discourteous newspapers, and sometimes even staging ambushes and sabotage against the German soldiers and war materiél.

What happened, then, was Philippe was now fighting an underground movement that was opposing Britain's enemies who in turn were following the exhortations of Charles. So Winston and Franklin really had to accept - although a bit grudgingly - Charles taking the top spot of the "Free French" government, and he made the famous broadcast calling on all Frenchmen to fight the Germans.

On the other hand, Winston and Franklin did realize that having a government in exile had some advantages. French still was one of the empires with extensive overseas holdings. Some of the French colonies, like Algiers, had standing troops that might support Charles and fight the Germans.

Philippe himself could not pretend he had any real independence over the German government - although that's what he did pretend. Worse, he had the bad luck to have selected a prime minister named Pierre Laval. Pierre was quite happy to be on the German's side as was his sidekick Joseph Darnand. Joseph was a particular albatross around Philippe's neck as he was head of Vichy's militia, or rather the Milice.

The Milice was Vichy's official internal security organization and was created to combat internal insurgency. Although officially separate from Germany's security organizations, for all practical purposes the Milice was a wing of the Gestapo. So by the time D-Day rolled around, Philippe and his government were clearly just doing the bidding of the Germans which included not only capturing, torturing, and summarily executing Resistance members but also shipping Jews off to the concentration camps. Dealing with Philippe and his buddies as anything other than full-fledged members of the Axis was no longer an option.

Now what was really odd was that Joseph seemed to understand the way the wind was blowing and tried to switch sides and join the Resistance. The absurdity of someone trying to join an organization whose members he had been torturing and murdering need no comment. "Non, merci," Les Résistants replied, and so Joseph ended up joining the German army as an officer in the Waffen SS. Bad move, Joseph, but not that it mattered.

There's no doubt that there were a good number of active Resistance fighters who risked their lives to fight the Germans and many were captured, tortured, and executed. The Germans also responded with disproportionate collective punishment, taking and killing multiple hostages in retaliation. The scenario inspired a generation of movies and television shows, not just those about the war per se that appeared from the 1940's and into the 1970's, but also spin-offs like "Errand of Mercy" where Kirk and Spock become resistance fighters for the Organians whose planet the Klingons have occupied.

Although most French citizens were sympathetic to the Resistance, it was also true that some "heroes" of the Resistance were scarcely that and assumed the roles only after the war. Although journalist and philosopher Albert Camus published the Resistance newspaper Combat, the role of Jean-Paul Sartre appears to be less active than originally touted. Some of his plays that supposedly had hidden anti-Fascist messages hid the messages so well that the German censors saw nothing amiss and allowed Jean-Paul's plays to be performed. German officers were also given front row seats and invited to the opening night parties. But to be fair there is also the story that Jean-Paul wrote anti-German articles for the underground newspapers.

Jean-Paul Sartre (à gauche)

Not as active as thought.

French General Philippe Leclerc led the first troops to enter Paris and obtained the surrender of General Dietrich von Choltitz (played by Goldfinger villain, Gert Frobe in the movie Is Paris Burning?). Charles followed shortly to a hero's welcome. By the end of 1944, all of France was under Allied control and in 1945, Charles became head of the provisional government.

Philippe, Pierre, and Joseph had fled to Germany where they were finally captured. All three were put on trial and condemned to death although Charles commuted Philippe's sentence to life imprisonment. At the age of 88 he would have been a good candidate for release on medical grounds but the feeling against him was so high that he remained in prison. He grew increasingly senile until he had no idea where he was, and died, still in prison, in 1951 at age 95.

Like Ike and Winston, Charles became the hero of the hour. The government tried to pick up where the Vichy government had begun using the Constitution of the Third Republic. But now Charles had to deal with other politicians, some who had decidedly different ideas of what France should become. So in 1946 Charles resigned as provisional leader and a new constitution - the Fourth Republic - was drawn up and ratified.

Charles didn't like the new constitution - he thought it needed a stronger executive branch - and one thing that irritated him was that the left wingers - and we mean real left wingers - i. e., bonafide Communists - were becoming more influential. Things got so fractious that by the early 1950's Charles said to heck with it. He retired to Colombey-les-deux-Églises and spent his time writing books.

By 1958 France was in a mess. The parties were having a horrible time forming governments since like all parliamentarian systems, they often had to form coalitions where different parties agreed to work together. But since they didn't, the governments kept falling apart and new elections kept being held. Although there was some reduplication, from 1946 to 1958 there were twenty - count 'em - twenty - prime ministers in France.

Turmoil in the French colonies wasn't getting any better. The people of Indochina - today Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia - had risen up against the French occupation and - to the surprise of the world, what many thought was a rag-tag army (called the Viet Minh) soundly trounced the French forces at Dien Bien Phu. France began pulling out of Southeast Asia.

But the immediate problem was Algiers, which was what they called an "overseas department". That is, it was part of France but just overseas.

But by the early 1950's, another group was clamoring for independence. These were the Algerians who traced their ancestry back to the African population (like the Berbers) and who were primarily Muslim. The trouble here is that there were also large numbers of native born citizens of French descent. These were the Pied-Noir (i. .e, the "Black Feet") who wanted to stay part of France. The Pied-Noir included most of Algiers' Jewish population who felt they would be better off as French citizens. One particularly sticky point was that the Pied-Noirs were allowed to be French citizens while the Muslim Algerians were not. Such an arrangement was complicated because there were about 1 million Pied-Noir (voting citizens) and 9 million disenfranchised Muslims.

In 1954, violence broke out in Algiers with a group of armed insurgents using terroristic tactics. And as they learned, terrorism is much less hazardous for the terrorists if you target unarmed civilians. People in rural areas were particularly vulnerable, and the attacks resulted in retaliations by the Pied-Noir. Tens of thousands of people were killed, and in fairness, there were a number of the Muslim Algerians who opposed the violence and even demonstrated in solidarity with the French citizens.

At this point the army generals stationed in Algiers (who of course were Pied-Noir) said the French government was just sitting on their rosy red culs in Paris and needed to do more to restore stability. But it was equally clear that the political system of the Fourth Republic - which kept changing prime ministers about every six months or so - was too unstable for any kind of proper action. So the generals had an idea.

Why not have the troops in Algiers simply invade France and take over? A dry run in Corsica worked fine - no one was hurt - and so the next step would be to send in paratroopers to Paris. But, they said, they wouldn't take such extreme measures if the government made a simple, wee, nay, trivial little concession.

Just bring back Charles, they said. Then they wouldn't send in the troops. True, Charles had been out of any real public office for 12 years, but the Generals figured he would know how to handle the situation if anyone did.

Charles agreed but only if it was done with proper parliamentary consent, and France would draw up a new constitution. This constitution would have to create a president with strong powers and a seven year term. And on top of that they had to give him, Charles, emergency powers for six months.

This sounded ominous. After all, one way to establish a dictator was to have the military pick the leader who then is granted emergency powers. At a press conference with Charles, a reporter brought this topic up and wondered if Charles might establish autocratic rule and reduce civil rights.

Charles, though, responded with a spittle flinging diatribe and said his record spoke to the opposite. He said at his age - he was 67 - the last thing in his mind was to go down in history as the first dictator of France. So the Fifth Republic was born with Charles as the President. This is the government still in force, and we know Charles did not make himself dictator.

It was around this time that the jokes started to appear about Charles and his new found power. One story supposedly told in France was that he and Mrs. Degaulle (Yvonne) were sitting at home and she noticed how cold it was in the room.

"Mon Dieu!" she exclaimed. "It is certainly cold in here!"

Smiling, Charles replied, "When we are alone, my dear, you may call me 'Charles'."

A similar joke was told by British comedian (and later serious journalist) David Frost on the American version of That Was the Week That Was. David was talking about new books that had just been published.

"And," he said, "there is How I Found God by Mrs. Charles De Gaulle."

Jokes or no, there was a problem in Algiers. And Charles had been called in to fix it - and the Pied-Noir hoped - to their satisfaction.

Sadly - for the Pied-Noir - Charles - if nothing else - was a world leader who learned from past history. Indochina had proven that if you have a large indigenous population that wants independence then no army, no matter how modern or well-equipped, will change anything. If you kept the status quo you will have perpetual civil war. So for Charles, the answer was clear.

Charles said he would put the question to a vote. And everyone in Algiers would vote - the Pied-Noir and the Algerian Muslims. At 1:9 Pied:Muslim ratio, there wasn't much doubt as to how the vote would go.

Merde alors!, that was not to the liking of the Pied-Noir Generals. They had called in Charles to stop the independence movement not give it what it wanted. There was now only one way out.

Yes, they would have to stage a coup and overthrow Charles. So four generals got together, and they planned to have troops parachute into France. They and the army - whom they were sure would follow their orders - would land at the airfields and then head into Paris. They would then arrest Charles and take over as a military junta. Problem solved, non?

Well, non.

It was technology that came to Charles's rescue. There was now a popular little device in the world called the transistor radio. The precursor of today's mobile devices, transistor radios were inexpensive hand held radios powered by batteries and were largely favored by the newly defined population group called the teenager. And teenagers included a good chunk of the enlisted men in the French army. Best of all, you could sit anywhere - on your porch, in a park, and even in an army barracks - and listen to broadcasts, any broadcast. Even a broadcast with Charles countermanding the orders of the junta.

The troops in Algiers listened to Charles telling them to ignore the orders of the misguided and fanatical "quartet" of generals. The soldiers obeyed Charles, and the four generals were arrested, tried, imprisoned, and eventually pardoned. Algiers went independent in 1962.

From 1958 to 1969 Charles was President of France. The government of France was unique, a parliamentarian system with a prime minister but also with a strong president wiyh more power than the PM. Charles would accept nothing less and such a system allowed him to promote his political philosophy and is now commonsensically called Gaullism.

Experts have trouble telling us just what Gaullism is. But we can safely say Gaullism was pretty much whatever Charles wanted. And basically he wanted to carve a separate and strong French identity that was pretty much independent of the British and Americans. If something was in France's best interest, c'est bon and if the Anglos didn't like it, well, that's tough bananas.

One thing Charles was adamant about. He wanted to keep England out of the affairs of Continental Europe since if the English crossed the Channel, they would want to call too many of the shots. So Charles also kept vetoing England's request to join the Common Market (officially called the European Economic Community or EEC). Eventually the EEC became the European Union. It wasn't until Charles was no longer around that Britain was finally able to join the EEC. That was in 1973 and then in 2016, England finally gave back what Charles always wanted.

But in his own time, where Charles caused a real hullabaloo was in 1966 when he gave NATO troops three months to "git out of town". That is, to evacuate France. NATO, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization for those who don't remember its purpose, was intended to stop the Communists in general and the Soviet Union in particular from invading Europe. Once France was free of NATO troops, Charles made a trip to Russia where he met with the (fairly) new leaders, Leonid Brezhnev and Alexei Kosygin.

This was strange. One of the reason the military had pushed for Charles in the Algerian Crisis was they didn't like the Communists and they figured he didn't either. But now the main defense against the Commies was gone and there was Charles rubbing elbows with them! But this was vintage Charles. If he thought something was in France's best interest, then who cares what anyone thinks?

For what it's worth, in 2009 - over 40 years later - French President Nicholas Sarkozy announced France would rejoin NATO. Notwithstanding that the Soviet Union had fallen apart nearly 20 years earlier, this event brought a resurgence of jokes - jokes which the CooperToons website with its goal of international amity will not repeat. Still the big gap that Charles wrought had been patched.

By the late 1960's, though, things weren't going all that smooth in France, Fifth Republic or not. Unemployment was up and this was also the time of the Great Youth Rebellion where kids were pooh-poohing Traditional Family Values by listening to rock music, wearing their hair long (the guys), and their skirts short (the gals). In France they were even borrowing English words! Using a hybrid patois called franglais, kids went on vacations during le weekend and might find a restaurant where they could eat un hamburger. And you think kids caused trouble at Berkeley or Columbia? Huh! Look what they did in Paris!

To say they trashed the town is an understatement. The kids took over the Sorbonne and spilled out into the streets. Things got so bad that at one point Charles was even thinking about asking for troops to be sent in from - get this - Germany.

Sacre bleu!

Actually Charles survived the student unrest. But he resigned as president in 1969. Although this is attributed to him losing a vote on another matter, it's likely his health played a as big a factor in the decision. Pushing 80, he was not a young man, and he died the following year.

Unlike JFK or Abraham Lincoln, Charles wasn't known for his sense of humor. His statements tended to be serious and even a little aloof. Of course, if he really said them.

One of his most famous statements was "Countries have no friends, only interests." We know he did say something sort of like that, but we can't think of it as a particularly witty statement. About the only joke attributed to him is when he vented his frustration about the Fourth Republic.

"How," Charles grumped, "can you govern a country which has two hundred and forty-six varieties of cheese?"

Despite les grands dangers of being called an overly skeptical scholar, there are some who for think this is not a real citation de Charles. Yes, it was reported in a number of books, particularly Le Mots du Général by Ernest Mignon. Other books give the quote in greater detail:

The French will only be united under the threat of danger. How can you govern a country which as two hundred and forty-six varieties of cheese?

The problem is that for a real quote there is a lot of variant wordings in the reporting. Not only do the words change but so does the number of cheeses. Sometimes we hear Charles mentioned a number as high as 265, and sometimes it's as low as 217. Such variations are almost a sure sign of a bogus quote.

Besides, although the first sentence, "The French will unite, etc., etc." is something Charles might say, the quip about cheese is quite out of character. So sadly we must say that unless fuller documentation is given, we must conclude this mot is pas du général.

References

The Last Great Frenchman: A Life of General De Gaulle, Little, Brown, 1993

"De Gaulle the Prophet", Noel F. Busch, Life Magazine, November 13, 1944, pp. 100 - 115.

"De Gaulle Sets Forth to Change the Face of Europe", Charles Murphy, Life Magazine, July 8, 1966, pp. 18 - 25.

1968: The Incredible Year, Life Magazine, January 10, 1969.

Oxford Guide to Effective Argument and Critical Thinking, Colin Swatridge, Oxford University Press, 2014.