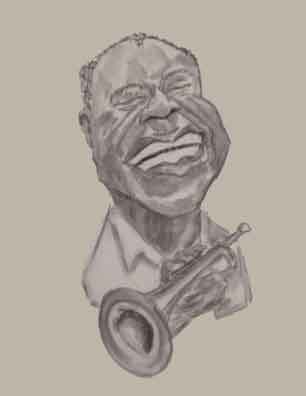

John Birks Gillespie

"Dizzy"

(Click to Zoom In and Out.)

Dizzy Gillespie

To Be or Bop Was Never The Question

The Diz

John Birks Gillespie was born on October 21, 1917, in Cheraw, South Carolina, the ninth of nine children of James and Lottie Gillespie. James was bricklayer, but music was a family tradition. Like his own father (also a bricklayer), James collected musical instruments (including a bass fiddle) and loved the big bands.

At first Dizzy showed little interest in music and his childhood was not a tranquil Ozzie and Harriet existence1. His dad was mean (Dizzy's word) particularly if he heard his kids were misbehaving. In fact, two of Diz's brothers ran away to escape James's heavy hand. "Every Sunday he'd whip us," Diz added.

Dizzy also said his older brothers ganged up on him. But when he complained to his mom, Lottie - trying to raise a large family - more or less shrugged her shoulders. So Diz learned early on how to defend himself. So despite his outwardly happy-go-lucky demeanor, people learned not to mess with Mrs. Gillespie's youngest son. Dizzy readily admitted he was mean like his dad.

When Dizzy was ten, James died of an asthma attack. Loss of a parent did not turn Dizzy to a life of reflection. If anything Dizzy was even meaner. It looked like the youngest of the Gillespies would end up in the pen or worse.

Then his music teacher, a lady named Alice Wilson, handed him a trombone. Learn to play it, she said, and he could appear in the school music show. Mrs. Wilson was surprised how Dizzy - who normally had a negligible attention span for school studies - would practice for hours.

During one of his practice sessions, Dizzy heard his next door neighbor playing a trumpet. Dizzy found this smaller instrument was more to his taste - not a surprise since his arms were too short to reach the trombone's longer positions.

But Dizzy was also living in a household with no father. Lottie working at low paying jobs couldn't support the family, so Dizzy got a job at a movie theater (part of the pay was getting to see the shows for free). He also worked retrieving coins from the bottom of a segregated swimming pool, working on road construction, and picking cotton.

In his not too ample spare time, Dizzy and some other musically inclined kids would get together to play their instruments. By now Dizzy had given up the trombone and kept to the trumpet. His progress was so good that one of the teachers from a whites-only school asked him to give his students some pointers.

Dizzy's childhood was also the era of the touring bands and orchestras. Given that many homes had neither electricity nor the money to afford a gramophone or radio, much of the music had to be live. Some of the traveling professionals heard Dizzy and let him sit in with them. We don't know if they gave him a bit of the cut.

While Diz was in the ninth grade Mrs. Wilson told him that the Laurinburg Technical Institute (still going strong) needed a trumpet player. The fact that Laurinburg was 200 miles north (actually it was about 30 miles across the North Carolina border) didn't bother him. But what did bother him is Laurinsburg was a private school and that took money. But, the administrators said, if Dizzy cleaned up his cantankerous ways and worked hard, he could attend without paying. Room, meals, and books were provided.

In 1935, when Dizzy was in his third year at Laurinburg, his family moved to Philadelphia. The City of Brotherly Love (aka the Town that Snowballed Santa Claus) suited Dizzy. After three days in Philly and still only seventeen, he got a job playing professionally. But Philly, although generally more relaxed than New York, was not a major entertainment center. So before the year was over, Dizzy, was up in New York.

New York City in the 1930's was the place to be for able musicians. This was the era of Swing, music that the people loved but not a genre that let the musicians show what they could do. Swing music was dance music and improvisation would send the dancers bumping into each other. But playing in a swing band was better than road construction in South Carolina.

One of Dizzy's first jobs was playing for the Teddy Hill Orchestra specifically for a tour of Europe (the usual trumpet player didn't want to go). What impressed his fellow musicians (and the listeners) was Dizzy's range and how he could rip off fast passages.

But what Diz really wanted was to play with a big name band. Like that of Cab Calloway2.

Footnote

Cab Calloway was one of the biggest acts to come out of the Harlem Renaissance and he had widespread popularity that cut across ethnic lines. In 1932 he even provided the music for the Betty Boop cartoon based on what was effectively his theme song, "Minnie the Moocher".

Cab's performances had to be seen to be fully appreciated. As the one who may very well be credited with the invention of the music video, it should be of no surprise he had a long and successful career. One of his best performances of "Minnie the Moocher" was when he had appeared in the hit film The Blues Brothers in 1980. What strikes an audience Past the Millennium is that what makes the scene appear dated isn't Cab's performance or his music. Instead it's the then-contemporary clothes and coiffures of the band and audience since in the 1980's there was still much of the "hippie" inspired styles around.

Cab Calloway

Popular

(Click to Zoom In and Out)

The story is that one of Cab's band members, Mario Bauza, had become friendly with Dizzy and helped him arrange an unusual audition. Mario lent Diz his costume - Cab's orchestra dressed in zoot suits3 - and on one number Cab noticed that the trumpet solo was being played by someone he had never seen. But he liked the playing and Dizzy became one of Cab's top performers even though Dizzy's clowning didn't always sit well with the normally cheerful Cab.

Footnote

zoot' suit' (zoot). n. a man's suit with baggy, tight-cuffed, sometimes high-waisted trousers and an oversized jacket with exaggerated broad padded shoulders and wide lapels. [1940-45. Amer.; rhyming compound based on SUIT] - Random House Webster's College Dictionary, 1991.

A similar but a bit more reasonable account is that there was an empty trumpet spot in Cab's band and Maurio, who didn't play full time for Cab, let Diz take his place for a night. Dizzy himself said he didn't actually introduce himself to Cab but just showed up in the suit and sat down in the band.

Dizzy began playing for Cab in 1940 and attracted attention from the first. One newspaper story about Cab's orchestra mentioned the "youngster" who was playing a hot trumpet in what was the first public mention of Diz's nickname.

It was also in 1940 that Dizzy - like many young men of his age - was summoned for the first peacetime draft in American history. Dizzy wasn't too sure about living in a rigid and regimented - and segregated - system regardless of the good intentions of the war effort. What happened after Diz showed up - like so much in Dizzy's stories - isn't quite clear.

One story is that because of his - ah - "demeanor" - he so concerned the army psychiatrists that they kept Dizzy under observation for several days before declaring him "unfit for service". But another tale is that he was first classified 1-A ("fit for duty") and it wasn't until 1943 - 2 years later - that he was classified 4-F - "unfit for duty". The primary records can't be examined since they were somehow destroyed in 1980.

It was shortly after Dizzy's return to Cab's band that he married a young dancer named Lorraine Willis. The two remained together until Dizzy's death although Diz was on the road for much of the time.

A job with Cab Calloway was one of the best. The pay and the prestige were good. But the tunes were often a bit sedate and sweet and (at least for Diz) easy enough.

Actually they were a little too easy. As was typical after the shows Diz and others would repair to the back rooms. There they would improvise complex melodies using - to the listeners of swing - increasingly discordant harmonies. No one knew what to call the music other than jazz "after the squares went home".

Diz and Charlie

Charlie Parker

He could cut it.

Although in later years Diz spoke well of his time with Cab, he abruptly left the band in 1941 and with acrimony. Cab was getting tired of Dizzy's horseplay: making faces, acting like he recognized a friend in the audience, and even throwing spitballs during romantic ballads. Cab would chew Diz out and he had been trying to lure another trumpet player named Jonah Jones to become his #1 horn man.

Cab believed Jonah's more straightforward jazz style - based more on Dixieland than what Dizzy was creating - would be more popular with the public. He hired Jonah but Dizzy did his best to discourage his new rival saying that all the plans had been worked out for the next year's shows and so Jonah wouldn't be doing any solo work for a year. Cab had other ideas and wrote a song especially for Jonah's debut.

The band was playing in Hartford Connecticut in September 1941. While singer Milt Hinton was on the stage a spitball came flying by and gobbed onto a spotlight. It was thrown by - no, not Diz - but by Jonah of all people! But Cab immediately taxed Diz who didn't suffer in silence.

Dizzy indignantly denied the charge and hard words followed. Diz then pulled a knife and stabbed at Cab but Milt got between the two men and knocked the knife off target.

But when Cab got into the his dressing room he found that although the knife had been knocked somewhat off target it nevertheless was on target enough to be most inconvenient. Fortunately Cab stood up most of the time during his performances.

Before he headed to the hospital, Cab informed Dizzy he was no longer employed. It took ten stitches to close the wound, and Downbeat Magazine's, October 15 edition blared "Cab Calloway 'Carved' By Own Trumpet Man!!" But within two years, the men had renewed their friendship. Diz might have had a temper but he was not petty.

Diz joined the band of pianist Earl Hines in 1942. The pay was a good $20 a night and the music was more jazzy. Earl's band wasn't just a guys' thing either. The piano player - yes, Earl had a piano player - was the young and oft times vocalist Sarah Vaughn.

Another member of Earl's band was a tenor sax man in his early twenties from Kansas City named Charles Christopher Parker, Jr. Yes, Charlie was playing a tenor sax at that time although we later know he excelled on the alto. But when a band must needs have a particular instrument sometimes you can't be too picky.

Evidently Diz and Charlie had met before. Some say it was in Kansas City in 1940 during one of Cab's tours. Other accounts put it in St. Louis. But it is clear they met someplace and both were playing with Earl Hines in the early 1940's.

Although Charlie was young - a few years Dizzy's junior - he had been around. When he was playing with Jay McShann in Kansas City, the band was driving to a job and the car with Charlie hit a chicken. Charlie told the driver to stop, and he got out and picked up the bird. As was common then, the band members were staying at private residences, and Charlie asked their hostess if she'd cook the "yardbird" for him. She said sure, and after that virtually everyone called Charlie "Bird". Dizzy - ever the contrarian - called him "Yard".

There are nightclubs for the public and there's nightclubs for the musicians. One of the latter was Minton's Playhouse at 118th Street in Harlem. There Dizzy, Charlie, and the others would take the stage and play what they wanted to.

The trouble is the stage got crowded. So if some young upstart wanted to join in, the veteran musicians said he had to audition by playing some horribly difficult tune and in an almost impossible key (such as F-sharp). Of course Charlie and Diz had long learned to play in any key and at any speed. Their tough demands drove most of the fledgling jazz players off the stage, but some had the wherewithal and stuck it out.

Like a lot of "sidemen" Dizzy didn't stick with any band too long. He left Earl in 1943 and joined Billy Eckstine - as did a number of Earl's band members (including Sarah and Charlie). By then Diz had written one of his early Afro-Cuban compositions "Night in Tunisia" and in Billy's band Diz also assumed the helm of composer and arranger. Soon he was doing the same for other groups and musicians including Jimmy Dorsey.

Although Billy could play the good-old-fashioned popular swing music and sang sentimental ballads (he had a smooth sonorous baritone voice), he would sometimes slip in fast paced songs with lyrics that seemed nonsense (as did Cab Calloway). Such singing was called "scat" but Dizzy said at least some of Billy's scat music was what they later called be-bop.

Bebop by name didn't appear until the mid-to-late 1940's. The term may have been from scat lyrics. After all, if a performer sang "boop-be-bop-bop-boop-be-dop", it was just a short jump to naming the music. Dizzy himself said someone would come up and say "Hey, play that tune. You know, the one that goes 'de-de-bop, do-bop-de-bop'." And so the music got labeled bebop.

One mistake is to think of bebop as a spontaneous and improvised art where the players - to cite one non-musical critic - "just pick up an axe and blow". True, a lot of bebop may not have been written down - and so in that sense was improvised. But a common characteristic of the songs was rapid and complex melodies played in unison. For such performances the players would have to work out exactly what their parts would be in the minutest detail. There are tapes of Diz and Charlie rehearsing where they play repeat takes in unison and literally note-by-note.

The time with Billy served Dizzy well. In 1944 he was voted the "New Star Award" by Esquire magazine (then and for decades thence one of the more "sophisticated" publications). After only seven months with Billy, the owners of the fancy Onyx Club in Manhattan asked Dizzy to lead an orchestra. However, his pre-selected partner, Oscar Pettiford, was not very reliable and would sometimes show up in no condition to perform. Or he might not show up at all.

Dizzy decided to form another band but entirely of his own choosing. Featuring Charlie Parker on sax, Max Roach (drums), Bud Powell (piano), and Ray Brown (bass) they played what anyone today would call real bebop.

Dizzy also garnered a good record contract. These records sold surprisingly well and soon the younger musicians would buy the records and play them at lower speeds to get the exact notes. As one young aspiring saxophonist once said, he didn't want to play like himself. He wanted to play like Charlie Parker. Trumpet players wanted to play like Dizzy Gillespie.

In 1945, disc jockey Sidney Tarnopol - known as Symphony Sid together with two well-known music publicists, Monte Kay and Mal Braverman - arranged for Charlie and Dizzy to play at New York's Town Hall. This was a prestigious theater. You not only had some of the most famous classical musicians perform there (such as Andrés Segovia, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Jan Paderewski, and Marian Anderson) but a lot of famous speakers appeared as well (such as early birth control advocate, Margaret Sanger). Dizzy and Charlie's concert was well received and suddenly the critics started taking bebop seriously.

Although the expense of a big band was high and logistically hard to manage, these orchestras were still popular. So Diz put together a big band called - what else? - the Dizzy Gillespie Orchestra. They toured the country including the then still-heavily segregated South.

Unfortunately the average music fan didn't care for bebop and the audiences in the South were lukewarm at best. Sometimes they just up and left. Diz returned to New York and it was clear that bebop was for smaller combos. So he and Charlie got another group together for a tour.

By now, though, Charlie was a big time heroin user and this affected both his playing and - to Diz's mind something equally important - his reliability. With some misgivings, Diz took the band to the West Coast to perform for three weeks at Billy Berg's Los Angeles nightclub.

All was well - at first. The public showed up including some big name movie stars. However after a while the audiences dropped off. Most people still weren't quite sure how to take the music.

It certainly didn't help that when Charlie ran out of drugs he would spend all his time trying to get the horse. Not having the connections he did in New York, he'd be gone for days. Diz finally hired a West Coast sax player named Lucky Thompson. Then whenever Charlie did show up he'd go into fits that there was a sax player in his place.

With the audiences getting smaller, the band was about to go back to New York. But where was Charlie? They looked around but he was nowhere to be found. Finally they gave up and left. It turns out that Charlie had been committed to the Camarillo State Hospital. He remained there for six months.

In 1948, Dizzy was featured in Life Magazine. His trademark beret was in evidence and had become a hallmark. Young ladies showed up for his concerts in berets, horned rimmed glasses, and yes, goatees (painted on, of course). Even actress Ava Garnder was seen in a nightclub sporting a Dizzy beret and glasses. She did, though, eschew the goatee.

In 1953, Dizzy acquired his signature bent trumpet. You may hear that a hefty member of the audience sat or stepped on it. But a more creditable story - given the actual shape of the bend - is the instrument was on a trumpet stand - supported by a plug of wood in the bell so it can be picked up ready to play - and someone fell against it. The resulting bent horn still sounded OK and in fact Dizzy liked the sound, either because the new shape produced subtle changes in the overtones or because the bend projected the sound above the audience. Afterwards Dizzy had his trumpets specially made with the bend.

Musical eggheads sometimes call a trumpet like Diz's a Ferguson Trumpet. That's because the trumpet virtuoso Maynard Ferguson designed a trumpet with a bend near the bell akin to Dizzy's. However, in Maynard's trumpets - sometimes called the "Firebird" model - the bend is less extreme than that of Diz's and a Ferguson Trumpet also has a trombone-like slide in the front that can be slid in and out with the pinky. The valves are also pressed with left hand, leaving the right hand to operate the slide.

Trumpet players of the well-dressed Southern Methodist University Mustang Marching Band play bent trumpets which some have referred to as Ferguson Trumpets. However SMU's horns are clearly much more Gillespie-like as they have no trombone slide in front. The bend is also at a much more Gillespie-styled angle.

For quite a while the SMU band was an all-male ensemble with a single majorette. Dubbed "90 Guys and a Doll" this tradition went by the wayside in 1977 and today there's plenty of gals playing alongside the guys. Yes, today ladies play the Gillespie trumpets.

Another characteristic of Dizzy's playing was that - contrary to all pedagogy for wind instruments - he puffed his cheeks. Some suggest that Dizzy had a medical condition that produced extra air passages in the throat or that the puffing of Diz's cheeks produced more powerful playing (the former explanation is possible; the latter untrue). Diz's own explanation was that when he began playing he taught himself and didn't know you weren't supposed to puff the cheeks.

Charlie Parker died of the effects of drugs and alcohol in 1955, age 34, and except for bebop fans, in obscurity. Although today it's seems heresy to say so, Bird remained largely unknown to the general public until 1989 when Celebrating Bird: The Triumph of Charlie Parker was shown on television.

Louis Armstrong

Satchmo

Dizzy, though, remained in the public eye and in perusing the newspapers about Dizzy's activities, the reader is struck how positive the stories are, particularly for someone playing music that was supposed to be so despised. Of course, there were plenty of people who considered bebop more noise than music. Sometimes they couldn't even get the name right! As one critic wrote when praising Louis "Satchmo" Armstrong and Dixieland:

"Satchmo” never seems to get any older. When he starts to blow that horn, he starts where other trumpet experts leave off. Dizzy Gillespie, Yard-bird Parker and Stan Kenton can have that  rebop [ sic]. Take it back to Fifty-Second Street.

rebop [ sic]. Take it back to Fifty-Second Street.

Louie himself wasn't so keen on the music. In a famous quote he said:

You got to like pretty things if you're ever going to be any good blowing your horn. These young cats now, they want to make money first and the hell with the music. And they want to carve everyone else because they are full of malice, and all they want to do is show you up any old way will do as long as it's different from the way you played it before. So you get all them weird chords which don't mean nothing, and first people get curious about it because it's really no good and you got no melody to remember and no beat to dance to.

Nevertheless, Dizzy was seen far more positively than otherwise. In 1956, his photo was featured in the article about jazz in - get this - the World Book Encyclopedia. That was also the year that President Dwight Eisenhower asked Dizzy to go on a tour for the State Department. "The Ambassador of Jazz" be-bopped his way through Africa, Asia, and the Middle East.

In the 1960's, jazz, even bebop, had become not only respectable but commonplace, old hat, and - dare we say it? - (augh! augh!) corny! That means the kids weren't listening to jazz, anymore. It was the parents!

Instead, the young and rebellious were now listening to (bleah) rock 'n' roll. And they weren't cool cats and chicks neither. They were teeny-boppers. Worse! They weren't listening to Dizzy's Gillespie's Salt Peanuts4. It was J. Frank Wilson's (retch, hurl) Last Kiss!

Footnote

Dizzy once performed "Salt Peanuts" at the White House. But instead of Dizzy singing the lyrics it was the then-President James Earl Carter.

None of this bothered the Diz and he kept going until January 6, 1993. Up to the end, Dizzy would pepper his shows with jokes and hijinks. At some point during a performance, he'd always tell the audience, "I'd like to introduce the band." Then he'd introduce the band members to each other who would go along with the gag and shake hands.

References and Further Reading

Dizzy: The Life and Times of John Birks Gillespie, Donald Maggin, It Books, 2005.

Dizzy Gillespie, Tom Gentry, Chelsea House, 1991.

To Be or Not to Bop: Memoirs ... Dizzy Gillespie, Dizzy Gillespie with Al Fraser, Doubleday, 1979.

"Dizzy Gillespie", Encyclopedia.com.

"Extended Biography", Joseph Stromberg, The Dizzy Gillespie Collection, University of Chicago.

"Dizzie Gillespie", The Telegraph, January 8, 1993.

"Timeline: 1940-1949", Jazz in America.

"Dizzy Gillespie and His Bent Trumpet", Joseph Stromberg, Smithsonian, October 21, 2011.

"BeBop: A New Jazz School Is Led by Trumpeter Who Is Hot, Cool, and Gone", Joseph Stromberg, Life, October 11, 1948, pp. 138 - 142.

"Cab Breaks Record in New York Theater Week", The Phoenix Index, November 23, 1940. p. 7, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"After Dark", Harry MacArthur", [Washington, D. C.], [Washington, D. C.] Evening Star, June 22, 1948. p. 7, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"Celebrating Bird", Gary Giddens (Director), American Masters, Public Broadcasting System, 1989.

"50 Great Moments in Jazz: The Emergence of Bebop", John Fordham, The Guardian,

Jazz: The First 100 Years", Henry Martin and Keith Waters, Cengage Learning, 2002, 2006, 2012.

Music in the Air: The Selected Writings of Ralph J. Gleason, Ralph J. Gleason, Toby Gleason (Editor), Yale University Press, 2016.

Louis Armstrong: An American Genius, James Collier, Oxford University Press, 1983.

"It Was One of Dizzy Gillespie's Last...", the Baltimore Sun, January 11, 1993.

"Jazz Trumpet Titan Dizzy Gillespie Dies", Claudia Levy, Washington Post, January 7, 1993.

Jazz: A Film By Ken Burns, Geoffrey Ward (Writer), Kens Burns (Producer, Director), Lynn Novick (Producer), Public Broadcasting System, 2001.