Ella Fitzgerald

(Click to Zoom In and Out)

You name 'em and Ella Fitzgerald sang with 'em. Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Benny Goodman, Dizzy Gillespie.

Ella's early life was not quite an Ozzie and Harriet existence (whoever they were). She was born on April 25, 1917 in Virginia. Her mom, Temperance (that's really her name but everyone called her Tempie) and dad, Bill, split up early, and Ella and Tempie moved to the Big Apple (Yonkers, actually). There Tempie met a man named Joe Da Silva. Although the family had little money, everyone seemed to get along.

Duke Ellington ...

... and Dizzy Gillespie

Ella sang with them.

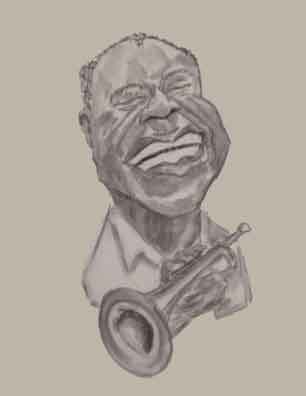

Ella got her first musical education singing in church. But like most kids she liked the popular music which at that time was jazz. Among the singers Ella aspired to emulate was the young Louis Armstrong although on the surface you can't imagine two dissimilar timbres. But Ella also became quite the dancer, and that was really her #1 choice of vocation.

In school she was a good student but while still in her mid-teens her mom died. So she dropped out of school and began earning money by what is now called busking. That is, she'd sing and dance on a street corner and the passers-by would toss coins into a cigar box. Her dancing got to be good enough that at age 15 she appeared at Harlem's famous Apollo Theater along with a young man named Charles Gulliver. They appeared as an act at other clubs and by all accounts they were quite a pair.

Louie

A different timbre.

Of course, dancing in clubs for little or no money wasn't a great job. So Ella soon found other ways to pick up some extra cash.

One job was as a runner. No, this wasn't appearing in athletic competitions. A runner was the person who collected money for the numbers bookies1. She also stood in as a look-out for businesses dedicated to gentlemen's special interests. If a uniformed representative of justice came sauntering along, Ella would bang on the door to warn the employees.

Footnote

The Numbers Game or the Numbers Racket is an illegal lottery that has been popular as long as governments have been making lotteries illegal. Also called "Street Numbers" (among other things), the game is still played but it is not advisable to do so.

The usual procedure is to go to the local numbers bookie (or "agent" as some prefer). You then pick out three numbers. The bookie writes them down on a sheet of paper along with your name. He then gives you your copy of the sheet and keeps the original.

The winning numbers are selected at the end of the day. The usual payoff was 599 to 1 (sometimes mistakenly called 600 to 1). So a $1 bet on a winning number would net the player a cool $600. But what made the numbers game really popular compared to legal lotteries is that some bookies would take almost any bet. Maybe 10¢ or less. The chance - however small - of laying down a dime and getting $60 was - and is - something that some people just can't turn down.

As you can see the odds are really stacked against the player. Even though you get paid off at 599:1, the true odd are 999:1. That's a 40% "vigorish" or house advantage. Popular numbers like 777 or the batting average of a popular baseball player - called "box numbers" - are paid off at lower odds like $400 to 1.

Of course, for the numbers game it isn't practical to pick the winning numbers from a bin or hopper. Instead one method is to take the last dollar digit of the amount bet at a designated racetrack in the first, second, and third races. For instance, if the amount bet at the track in the races was $593,488, $402,867, and $287,944, then the winning number would be 874.

There are other ways of picking the winners. Instead of the digits of the payout of the races, the numbers might be the last three digits of the daily track attendance. Also winners could be determined from the last three digits of the daily balance of the US Treasury. Or the winning numbers might be culled from daily transactions of a local clearing house.

It didn't take long for the authorities to notice the teenage girl hanging around the bookies and sporting houses. So she was sent to Public School 49 which specialized in taking in such wayward waifs to "straighten them out" to borrow a phrase from follicularly challenged gentlemen from quaint towns in the American Southwest. Ella quickly grew to hate the place and soon ran away.

No ifs, ands, or buts about it, she was going to be an entertainer and decided to concentrate on singing. This wasn't such a crazy idea, at least not in New York. A lot of the famous clubs hosted amateur nights where aspiring singers could stand up in front of an audience and sing while accompanied by a big name band. If the singers showed ability, they might attract the attention of a talent scout.

So on January 21, 1934, Ella went to the Apollo theater and sang to the audience. The winner was selected by having contestants come back on stage at the end of the show. As each took their bows, the vigor of the applause dictated the winner of the $10 prize.

Ella sang "The Object of My Affection", the hit tune by Pinky Tomlin. But because she got a flash of stage fright, her voice cracked and she had to start over. She thought she had blown the contest, but when she came back on stage and took her bow, the crowd roared. She won first prize.

After the show Benny Carter, the band leader, arranged for Ella to try out with Fletcher Henderson. Unfortunately, Fletcher didn't offer her a job but at least her performance at the Apollo had gained her some attention.

Ella next entered another contest at the Harlem Opera House. This time she didn't just win a prize but landed a one week-engagement. A reporter for the New York Age was in the audience and for the first time Ella was mentioned in the newspapers.

Still Ella's career didn't take off at least not professionally. She still had to spend quite a bit of her time busking. And that's the way things were in 1935.

But 1935 was the year that bandleader and drummer William Henry "Chick" Webb was playing at the Savoy Ballroom. Together with the Apollo and the Cotton Club, the Savoy was the hottest of the Harlem hotspots. Diminutive in stature but not in ability, Chick was still not quite the crowd-pleaser as was Duke Ellington or Earl Hines. So Charlie Buchanan, the manager of the Savoy, suggested Chick might do better if he added a female vocalist to the group.

Charles Linton, Chick's principle balladist, decided to scout for talent. He asked one of the chorus girls if she knew a girl singer. Well, she said, there was this girl Ella who had won the Apollo talent contest. But now she was scraping by singing on the street corners. Charles said to bring her in.

A few days later Ella came in. Charles asked her to sing something. After the song, he mentioned that her voice was soft but that wasn't a problem since a microphone would bring it out. So he took her to meet Chick.

Chick almost threw Charles out of the room. It wasn't any problem with Ella's voice but with her appearance. For one thing she was still only seventeen but looked a lot younger - too young for a nightclub performer. Also since she had been spending most of the time living on the street, Ella did have a disheveled look, and the only thing she had to wear was common street clothes. She certainly didn't look like someone who would bring in the customers.

But after some arm twisting (which included Charles threatening to quit the band), Chick finally promised to give the girl a two week tryout but without pay (Charles made arrangements for Ella to eat at a nearby restaurant). After two weeks and asking the opinion of other musicians, Chick decided to keep Ella on full time but not for much money.

Although Ella wasn't an immediate hit, everyone recognized she sang well. Her style also fit with the swing bands. Right after Ella began singing for Chick, a reporter from Metronome magazine stopped by the Savoy to listen to Chick and his band. He gave the band a B+ but mentioned that their young singer could be going places.

Chick had been making records for quite some time. They were, though, mostly instrumental numbers. But the era of the singers was at hand, and now with Ella in the group, Chick was able to focus on vocals. By June 1935, Ella was cutting platters.

Even when Ella was singing Dixieland songs with "scat" lyrics she kept with a swing style which was popular with the fans. Soon people were packing in the Savoy to listen to Chick's band with the new singer. What was unusual about Ella is that she could take what were novelty tunes or even kids' songs - like "A-Tisket, A-Tasket" - and turn them into swing tunes.

Ella was still quite young and Chick and his wife, Sally, kept their eye on her. Chick, though, was never in good health, since a childhood accident had impaired his physical development. He died in 1939 from spinal tuberculosis.

By that point, though, Ella's singing had been a major factor in the increasing popularity of the band. With Chick gone, she took over the band. Although it was unusual, there were some women band leaders including Blanche Calloway (yes, she was Cab's sister). However, the band continued only for another three years. By 1942 the war had disrupted much of the popular entertainment, particularly entertainment that was largely composed of able bodied men of military age.

Blanche Calloway ...

... and Little Brother Cab

(Click on images to zoom in and out.)