Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass

He wrote history and literature.

Frederick Douglass is the most famous of the ante-bellum and Civil War abolitionists. No one can deny his fame was due to his oratorical skills and his political activism ranging from abolition to rights for all (including votes for women). But mostly we know of Frederick because the three editions of his autobiography, A Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, My Bondage and My Freedom, and The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass still make good reading today. The first two editions the Narrative and Freedom can even be found formatted for some of the new electronic readers. That is the mark of a classic.

Frederick's books, although written with the narrative style of the nineteenth century, don't conceal his dry sense of humor which would become sardonic when dealing with the then mainstream philosophy on race and civil rights. When Frederick escaped from slavery and began a new life in New Bedford, Massachussetts, he found discrimination and bigotry were very much alive and well in the North. Few people - even abolitionists - believed in equality of the races in the modern sense. His description of visiting the sights in Dublin (where he had to flee to avoid being arrested for his supposed conspiracy with John Brown) will set even the most former liberal of former liberals (and who don't realize they aren't liberals anymore) laughing if a bit self-consciously.

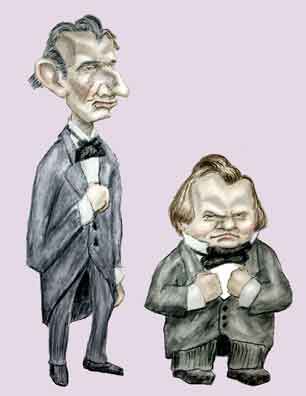

Frederick had sharp opinions on the political leaders of the day. He pointed out that Lincoln - from an abolitionist viewpoint - moved with irritating glacialness. But he also acknowledged that Lincoln could not get too far ahead of public opinion if he was to succeed at his twin goals of both preserving the Union and ending slavery. All in all, Frederick felt no one else could have handled the Civil War as well as Abraham Lincoln.

However, Frederick could abide neither Stephen Douglass nor Andrew Johnson. Frederick's lack of respect of Stephen was certainly influenced by Stephen taking regular and sarcastic jabs at him - naming him by name during the famous debates with Lincoln in 1858 - not to mention Stephen's free bandying about ideas of white superiority and using racial epithets of a type that even the Democratic papers bowdlerized. Frederick's description of Johnson was far from flattering, and he felt Andrew was no friend of the African American community. Frederick also harbored doubt of Andrew's character and judgment and felt obliged to write that when Andrew had given his speech at Lincoln's second inaugural, the vice president had fortified himself too much toddy. That Andrew did imbibe too much and ended up delivering an incoherent and rambling address is known from what other people said about that day, including Lincoln himself. But if you want to cut Andrew some slack, he was suffering from a bad cold and in the 19th century a hefty snort was recommended as a way to relieve the symptoms.

Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas

Respect for one; Detestation for the other.

It is forgotten, though, that many other slaves left accounts of their lives. Two books of note are Twelve Years a Slave by Solomon Northrup, a free black man who was kidnapped and sold into slavery, and Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl by Harriet Jacobs who was unusually frank (for the time) about the abuse subjected on slave women and the means they used to find protection. But Frederick's biographies stand out because they are both good history and good literature written by a man who became a noted public figure throughout the majority of the nineteenth century.

At one time almost impossible to find as hardcopy, virtually all of the slave narratives are now online. The best source is certainly Documenting the American South where the texts are in legible and clear HTML format. You can read the famous Confessions of Nat Turner which is as close as we can get to a first hand account of an actual slave rebellion by the leader. Although Nat's approach to destroying slavery remains controversial and troublesome to many in today's America, a number of modern and mainstream public figures and citizens have advocated similar methods to achieve their own goals - provided one makes allowances for advances in technology, military and social conventions, and the nationality of the people involved. On the other hand, Frederick would have certainly opposed Nat's extreme and (we must say) brutal measures and was even opposed to - and argued against - John Brown's attack on Harper's Ferry. Frederick, though, was not opposed to armed struggle in principle, and did work with John on a scheme to start a slave rebellion centered in the Appalachians.

Recently there has been renewed controversy on how well the slaves were treated by their owners and the degree of harmony that existed between the black and whites in the ante-bellum era. Some textbooks - required reading in certain schools - say the majority of the masters treated their slaves well. Now, defenders of the "slaves-were-treated-well" view have sometimes gotten quite hot under the collar when challenged and go into spittle flinging diatribes that the "slaves were treated bad" position is (ptui) revisionist history put forth by radical liberals, socialists, and other Enemies of American Freedom. Of course, why people get upset if you say slaves were treated badly seems a bit strange unless you want to believe that slavery - at least in the United States - was really OK.

To sort (accurately) through this thorny topic, we must - as always - ask politely just what we mean by treating someone "well". To do that we need to sift amongst the effects the "peculiar" institution had on the slaves as a whole, the effect on individuals, how the laws and customs applied to all people regardless of color, and what the slaves themselves said versus what they actually thought. But above all, we need to decide whether in that day and age treating a slave "well" meant the same thing as treating a free US citizen "well".

In bolstering opinions you can certainly go through slave accounts, and by selecting those you want and tossing out the others, you can find slaves who said they were treated well. After emancipation it is also true that many former slaves lived in extreme poverty and for some the conditions were at least as bad, if not worse, than during their days as slaves. Relatively speaking you might say the latter slaves had been treated "well".

But counting the number of times slaves or owners said the slaves were or were not treated well is not a very productive way to resolve the issue. Instead let's look at how the slaves were actually treated as reported by objective and disinterested visitors to what was a showcase plantation. This plantation, by the way, was run by a slave owner about whom modern readers will never - that's never! never! never! - read in schoolbooks was a cruel master. Au contraire, we learn he treated his slaves "well". That worthy is, of course, the Father of Our Country, George Washington.

George, we learn, went more than the other mile in treating his slaves "well". After all we are told repeatedly that George recognized the marriages of his slaves, refused to break up slave families, and freed all his slaves in his will. In fact he early resolved that he would not even buy more slaves. On an individual level, he was quite generous to - as he termed them - his "people". He even let one of his cooks, a culinary expert (and slave) named Hercules, sell the leftovers and pocket the money - $200 a year, which was big bucks in the 1797. George also avoided inflicting corporal punishment on - again as he said - his "people". Of course you have to temper these statements with the fact that a close reading of George's correspondence indicates he may not have done the thrashing because there was an overseer to do the job. We should also mention that Hercules, George's cook, eventually ran away.

But just how "kind" a master was George - or more exactly how did impartial visitors see George as a slave owner? Since George and Martha had more than 600 visitors a year at Mount Vernon (some who simply showed up unannounced and were put up for a day or two), it isn't surprising that we have some candid contemporary impressions on George the Master. Two accounts are particularly noteworthy because they were not by Americans but Europeans, both of whom admired George, who by that time was the most famous man in the world.

One of the visitors was a particularly garrulous Englishman named Richard Parkinson who in 1798 was thinking about leasing part of Mount Vernon. From Richard we learn George kept the slaves to a strict allotment. "General Washington", he wrote, "weighed the food for all his Negroes, young and old, and as he was a man of minute calculations, he probably knew what they cost, to a fraction." But Richard also noted that George was not particularly generous. "He [that is, George] regularly delivered weekly to every working Negro two or three pounds of pork [that's about 4 to 7 ounces a day for workers], and some salt herrings, often badly cured, and a small portion of Indian corn." Now although the meat portion for the workers is not necessarily an inadequate diet for someone who sits on their rear end in an air-conditioned office, it is certainly not sufficient for farm workers kept continually at their jobs from sunup to sundown in Tidewater Virginia. Being in the fields during all daylight hours was, in fact, what George expected as we know form his own writings. We also know that George's "people" complained they didn't get enough to eat and - ah - supplemented their diet using methods that caused George continual consternation. At least at one point, George did increase the food rations - which we guess was treating his slaves "well" - or at least it was treating them better than not giving them more food.

George was a "kind" master.

Richard also commented on how "well" George dealt with his slaves on a personal basis. He was not, it seems, a particularly kind and paternalistic owner. Or as Richard said, "Only take General Washington as an example: I have not the least reason to think it was his desire, but the necessity of the case: but it was the sense of all his neighbors that he treated them [the slaves] with more severity than any other man." Also when just talking with his slaves, George was abrupt and impatient. Richard added "The first time I walked with General Washington among his Negroes, when he spoke to them, he amazed me by the utterance of his words. He spoke as differently as if he had been quite another man or had been in anger."

Richard wasn't the only visitor to note how "well" George treated his slaves - which we are concluding wasn't very. The Polish statesman Julian Niemcewizc, who also visited George in 1798, found the slaves' accommodations were crude in the extreme even when compared to that of poor whites. Julian wrote that the slave homes "are more miserable than the most miserable of our cottages of our peasants [emphasis added]. The husband and wife sleep on a mean pallet, the children on the ground; a very bad fireplace, some utensils for cooking." The clothes were barely subsistence, "a jacket and a pair of homespun breeches per year". The young children did not get any clothes at all until they reached a certain age. So in treating his slaves "well", George had them live in the crudest of huts with virtually no furniture - not even a bed. From these descriptions even if George - certainly in his own mind a "kind" master - was not a sadistic owner in the Simon Legree sense, it does not sound like he treated his slaves particularly well.

Perhaps one of the most objective reporters of antebellum America was Frederick Law Olmstead, who later would design Washington's National Zoo and New York's Central Park. As a young man Frederick traveled throughout the South and witnessed slavery first hand. His views are particularly valuable since although he was from New York and thought slavery was wrong in principle, he was not an abolitionist and acknowledged that the southern attitude toward slavery might indeed be correct. But his travel journals - sent as letters to various newspapers - do not report a particularly happy and contented society. In general, the owners had far more complaints about their slaves, and like George, only gave them the minimum necessities to survive. When Frederick met a small Mississippi farmer who actually fed his slaves the same food he ate and let them set the pace of the work, Frederick was clearly pointing out an exception not the rule. As far as how "kind" the slaves in general were treated, the same - and we emphasize, white - farmer said he would rather be dead than be a slave on one of the big plantations.

Frederick Law Olmstead

Objective by his own standards.

You also have to wonder how a system that treated slaves with "kindness" can be reconciled with contemporary accounts that show that there was a real and continued fear of the slaves. Some apprehension was simple non-specific xenophobia, but there was also active fear of slave resistance. Slave owners worries ranged from fear of being poisoned by their cooks (and some were poisoned by their cooks) to full out-and-out rebellions. There were also regular patrols - the infamous "paterollers" - that were sent out to apprehend, jail, and whip the slaves for no other reason than being from their homes without written permission. Certainly permitting 39 lashes simply for visiting a neighboring farms to see a spouse and children who belonged to other owners is not "kind" treatment by today's definition. No doubt the owners felt it was merely being firm, but the slaves didn't think so.

The truth is the vast majority of slaves who spoke candidly showed considerable discontent with their lot. Naturally the slave owners spouted that the discontent resulted from various causes not related to their treatment. Outside agitation was often cited. I mean, if those damn Yankees like William Lloyd Garrison, Wendell Phillps, and yes, Frederick Douglass would just shut up, the slaves would be happy and contented with their lot and realize how "kind" they were actually treated. Of course, slave owners also had to contend with that pesky mental illness that was specific to people of sub-Saharan African descent - called draeptomania - which caused the slaves to have an irrational urge to run away. White planters were warned to watch for symptoms of the illness, the most prevalent was the slaves becoming sulky and discontented. The remedy - prescribed by the physician who first described the "disease" - was "whipping the devil out of them" - obviously "kind" behavior as are all acts that cure the ill.

Were some slave treated well? Once more you have to consider that there was a different standard for slaves and free whites and the manner in which the statements were recorded. Nat Turner, whose band of insurgents later killed his master and his entire family (and more than fifty other whites), said - or was reported to have said - Mr. Turner had been a kind and indulgent master. But this was in a "confession" that had been taken down by a white lawyer for submission to the court. But even there we read Nat had been whipped - by his "kind and indulgent" master - for the dastardly deed of saying he thought slaves should be free.

There are also the WPA interviews where some slaves spoke of being treated well. But such narratives must be read cautiously and the answers could change depending on the circumstances - such as what the race was of the interviewer. One former slave spoke of how "fair" she had been treated when interviewed by a white writer who was posing as a social worker. But when interviewed by a young black man her remarks on the white community were bitter and sarcastic.

So yes, there were owners of slaves who did not regularly whip their slaves for no reason, deliberately starve them, or kill them for minor misdeeds - as long as the slave refrained from wanting the full rights of a United States citizen. But physical abuse - from a minor cuffing to life threatening floggings - was commonplace. Even the "kinder" masters put restrictions on slaves' travels, sold off children and spouses, and provided minimal subsistence (or less) food and clothing and housing. A slave who was suspected of even considering running away was risking jail, beatings, and being sold. The slave holders - or an antebellum Humpty Dumpty - would have said all this was treating a slave "well", but a humble CooperToons opinion is it was not.

Sadly, racism is, of course, alive and well in all countries, although usually - but not always - couched in new language. Many modern racists still target the old groups in non-racial terms - usually economic or citing law and order - but also direct their ire at new ethnic groups and religions which have become socially acceptable to hate. Of course, even the most blatant of middle class racists - regardless of race, creed, or national origin - deny with spittle flinging diatribes that they are like the racists in Frederick's time. Which is absolute nonsense - they are so in every respect, if not worse.

The point and absurdity of any racial doctrine is that race is a concept that is really defined via human perception and cognition and not by any objective scientific criteria. Variability of - quote - "racial characteristics" - unquote - within a give - quote - "race" - unquote - have been shown to be greater than the average characteristic differences between races. So in a nutshell, we recognize race by the same phenomenon that causes people who look at blurred photographs and out-of-focus videotapes and see ghosts, UFO's, and the Loch Ness Monster. So any attempts to define race by some quantitative or scientific method will inevitably fall down with a resounding splat. Not even a computer capable of winning at Jeopardy can do it.

References

As we said, the Internet is one of the best sources for primary material on ante-bellum and Civil war history even though popular - quote - "Internet resources" - unquote - have also become major sources of spreading ignorance, superstition, and pseudo-science. Others, like Documenting the American South stand equal to any major research library - largely because they are posted by major research libraries, in this case by the Library of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Some of the more notable sources, both at UNC and elsewhere are:

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself, Frederick Douglass, http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/douglass/menu.html. Frederick's first book written and published before the Civil War. It focuses on his life as a slave.

My Bondage and My Freedom, Part I: Life as a Slave. Part II: Life as a Freeman, Frederick Douglass, http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/douglass55/menu.html

The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, Written by Himself. His Early Life as a Slave, His Escape from Bondage, and His Complete History to the Present Time, Including His Connection with the Anti-slavery Movement; His Labors in Great Britain as Well as in His Own Country; His Experience in the Conduct of an Influential Newspaper; His Connection with the Underground Railroad; His Relations with John Brown and the Harpers Ferry Raid; His Recruiting the 54th and 55th Mass. Colored Regiments; His Interviews with Presidents Lincoln and Johnson; His Appointment by Gen. Grant to Accompany the Santo Domingo Commission—Also to a Seat in the Council of the District of Columbia; His Appointment as United States Marshal by President R. B. Hayes; Also His Appointment to Be Recorder of Deeds in Washington by President J. A. Garfield; with Many Other Interesting and Important Events of His Most Eventful Life; With an Introduction by Mr. George L. Ruffin, of Boston, Frederick Douglass, http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/dougl92/menu.html, The titles and subtitles of nineteenth century literary works did tend to overdo it a bit but that was the day before jacket blurbs could give you some idea of what the book was about. This was the last of Frederick's biographies and contains a lot about his life following the Civil War. Frederick became a leader of the black community and held a number of important jobs both in the private and public sector. After the Civil War he continued to work for civil rights, including those of women.

Twelve Years a Slave: Narrative of Solomon Northup, a Citizen of New-York, Kidnapped in Washington City in 1841, and Rescued in 1853, http://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/northup/menu.html. Solomon was a free black man who was kidnapped and taken to the south. Such kidnappings were common and there was, of course, usually no legal redress.

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself, Harriet Ann Jacobs and Lydia Maria Francis Child, http://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/jacobs/menu.html. Harriet's book tells the story from the perspective of a young adolescent woman.

The Confessions of Nat Turner, the Leader of the Late Insurrection in South Hampton, Va. As fully and voluntarily made to Thomas R. Gray, In the prison where he was confined, and acknowledged by him to be such when read before the Court of Southampton; with the certificate, under seal of the Court convened at Jerusalem, Nov. 5, 1831, for his trial. Also, an Authentic Account of the Whole Insurrection, with lists of the whites who were murdered and of the Negroes brought before the court of Southhpampton, and there sentenced, &c. http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/turner/menu.html. Though there is some controversy whether these were actually Nat's words, the unrepentant tone suggests the sentiments are indeed Nat's who felt he had been chosen as the leader who who would bring an end to slavery. When asked by Thomas Gray, who took down the confession, if the failure of the revolt made him change his opinion, Nat simply replied, "Was not Christ crucified?"

The South Hampton Inssurection, Sidney Drewy, (Neale, 1900), http://www.archive.org/details/southamptoninsur00drew. The first study of the Nat Turner revolt and a most interesting example of how even educated people viewed race at the beginning of the twentieth (or end of the nineteenth) century. The author - whose title is trumpeted as an "Honorary Scholar in History" at Johns Hopkins University (one of America's first research universities) - clearly was a believer in the benevolence and kindness of the Southern system. The book shows that even after the Civil War the idea of racial equality was far from a widespread belief as the book is peppered with passages like how the insurrection was "not due to cruelty of the slave system", that the "weak and cowardly have participated, while the brave and intelligent slaves, in general, remained loyal", and "affection existed between master and slave which has been handed down to their descendants, which dispelled that physical aversion and incompatibility of character and temper of the superior race for the inferior." Nevertheless there is more detail on the revolt here than in Nat's original Confessions and a number of people living at the time of the revolt, including a number of blacks, were interviewed.

Books by Frederick Law Olmsted, who we mentioned was the architect who designed (among other landscapes) Washington's National Zoo and New York's Central Park, traveled extensively, as a young man, travels which included trips to the American South. He wrote up articles on the fly and sent them back to Northern newspapers. Hard copies of Frederick's original travel books are expensive, although later editions are available in less pricey reprints. But all the titles can also be found as online editions, such as the University of Pennsylvania Online Books website at http://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/. Frederick's books are specifically found at http://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/webbin/book/lookupname?key=Olmsted%2c%20Frederick%20Law%2c%201822-1903. The Cotton Kingdom is the best place to start as it is a compilation and abridgment of his earlier books of his travels in the South.

Frederick Olmstead was not concerned with slavery per se, but simply wrote about his travels, much of which involved finding a place to stay. As a visitor - often only for an overnight stay in private homes - Frederick did not have much contact with the day-to-day interactions of the owners with their slaves. He did see some cases of "kindness" but more often he saw owners exasperated at the trials and tribulations of how to "handle" their slaves. And once he saw a brutal whipping - normally done out of the sight of visitors.

Also, the modern readers should avoid being over censorious at Frederick's (Olmstead, that is, not Douglass) representation of the slave's speech. Yes, it certainly comes off as condescending, but so did many of the WPA writers in the 1930's when recording the slave narratives. Even Frederick Douglass in his writings would try to phonetically represent the "slave speech". But Frederick - both Douglass and Olmsted - and the WPA writers were making an honest attempt to represent the sound of the dialects not realizing that some of the spellings could also fit with mainstream American English. After all, everyone pretty much says "wuz" for "was".

Walks and Talks of an American Farmer in England, Frederick Law Olmsted, George Putnam, 1852. Frederick's earliest book of an early trip to England with his brother.

A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States, with Remarks on Their Economy, Frederick Law Olmsted, Dix, Edwards, and Company, 1856. Frederick's first book of his travels in the slave states.

A Journey Through Texas - Or a Saddle Trip on the Southwestern Frontier, Frederick Law Olmsted, Dix, Edwards, and Company, 1857.

A Journey in the Back Country, Frederick Law Olmsted, Mason Brothers, 1860

Frederick Douglass, William McFreely, W. W. Norton (1991). A modern biography of Frederick Douglass, this has been criticized by reviewers as somewhat straining in its psycholanalysis about what shaped Frederick's personality. Still it is a good and readable book which does stick to points of facts regarding historical events.