Frederick Fennell

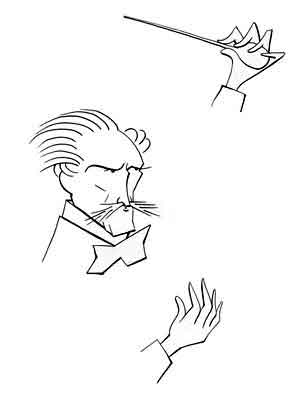

Curmudgeons who have never played an instrument tous ensemble will grump, "Just what the hey does a music conductor do?" Huh! Just stand up and wave their arms and make funny faces at the orchestra!

Weeeeehhhhheeeeeeeeeellllllll, not quite. True, at the suggestions of his teachers, Lenny1 once practiced in front of a mirror. But he kept busting out laughing and so had to stop looking at himself.

Lenny

He couldn't help laughing.

On the other hand, anyone who has sat in a performing ensemble - good bad or indifferent - knows that the conductor "interprets" the piece. That means he sets the time (allegro can be anything from 120 - 156 beats per minute) and the dynamics (the difference between pianissississimo and pianississississimo is pretty much a matter of taste). He or she determines how staccato are the staccatos and how legato the legatos2. They also must deal with the individual members on how they play to produce the desired balance of the instruments.

Footnote

That reminds us of the old Paul Lynde joke from the Hollywood Squares. The host, Peter Marshall, asked Paul "Where do you find 'staccato' and 'legato'?"

Paul answered, "The police are dragging Lake Michigan right now."

But such explanations rarely satisfy the curmudgeons That's all they do? Huh! That's not much for the fat salaries the top notch conductors pull in.

Besides, why all the conductor jokes?

What's the difference between an orchestra and a freight train?

A freight train needs a conductor.

What's the difference between a conductor and God?

God doesn't think he's a conductor.

It is true that some conductors are noted for being, well, rather stern in their manner. Stories of the Toscanini Temper abound and one record producer remembered that during a rehearsal the cellos "smeared" a passage. Arturo hit the roof, screamed, yelled, ripped his shirt, and clawed at his chest, actually cutting himself. Arturo had to leave the podium, and the orchestra was informed the rest of the rehearsal was canceled.

Such shenanigans make good stories but seldom impress top flight professionals. One writer and friend of Arturo later interviewed a number of the members of the NBC Symphony, the last orchestra that Arturo conducted. As the recordings attest, the NBC Symphony was staffed with the best musicians available, and the writer wanted to know what it meant to serve under the baton of the century's most renown conductor. To his surprise it didn't mean that much. They were decidedly unimpressed with Arturo's temper tantrums and didn't see how it helped them play better.

Arturo Toscanini

Legendary

During one rehearsal Arturo abruptly stopped the playing. "Again!" he shouted. They repeated the passage and once more Arturo stopped them. "Again!" he called and had them play the passage over. He kept this up over and over until finally he stopped them once more. Fixing them with his steely eye he asked, "Is there not an accent?" But why not just say he wanted more of an accent in the first place, one musician wondered. Why waste everyone's time?

Now there's no doubt that some people choose to become conductors - like some people choose to become business managers - as part of their own personal therapy program. But that wasn't true of Frederick Fennell. After all, anyone who played under the direction of Frederick found it was actually fun! And Frederick seemed to have a good time, too. If you saw him conduct Sousa marches you might guess that he played a good tennis game with a strong backhand.

What distinguished Frederick was that he pretty much singlehandedly launched the revolutionary emergence of the wind ensemble and brought it to parity with the symphony orchestra. Before that you just had a (ptui) "band" whose only function in the universe was to play out of tune marches during the football game halftimes.

Frederick was born in Cleveland in 1914 and showed musical talent early. Concentrating on drums he attended the National Music Camp and on July 26, 1931, at age 17 Frederick played in a band conducted by John Phillip Sousa. Frederick loved JP's marches, particularly "The Black Horse Troop".

For college Frederick chose - and was accepted in - the Eastman School of Music at Rochester, New York. After graduating with bachelors and masters degrees, he joined Eastman's faculty.

One junior high school teacher said that a "wind ensemble" is just another name for a band. That, though, isn't quite correct. When Frederick established the Eastman Wind Ensemble in 1952, he immediately cut down the size. Bands tended to be big - the size of a symphonic orchestra but where the clarinets, flutes, and cornets (or trumpets) were beefed up in number and extra sections - saxophone and euphonium (baritones) - were added. Even in the smaller sections - like trombones and French horns - there were usually two to three players per part. And as anyone knows, such bands tend to be loud and even raucous.

The smaller size of the wind ensemble - 40 players or less - gave a much cleaner and - yes - quieter sound. This makes a concert a more enjoyable experience and the Eastman Wind Ensemble became quite popular.

But it was Frederick's recordings that really made a difference in elevating the status of band music. Mostly released by Mercury, the records were widely sold and Frederick and the Eastman Wind Ensemble soon garnered an international reputation. Frederick edited a number of compositions for the band (if we can still use the term) but he also got composers to write original works. Of course he recorded with other bands as well and even today if you hear something played by a band, it's likely a recording with Frederick at the podium.

Frederick relinquished his Eastman baton in 1961 and later became the director of the Dallas Wind Ensemble and the Tokyo Kosei Wind Orchestra. He also established a wind ensemble at the University of Miami.

But we must be honest. No one is perfect. After leaving Rochester Frederick became the associate director of the Minnesota Symphony Orchestra.

Yes. An orchestra.

With violins.

References and Further Reading

"The Life of Fennell", Toru Miura, The Band Post,

"Frederick Fennell", Jeremy Grimshaw, AllMusic.

Frederick Fennell and the Eastman Wind Ensemble: Transformation of American Wind Music Through Instrumentation and Repertoire, Jacob Edward Caines, Masters Thesis, University of Ottawa, 2012.

On Becoming a Conductor: Lessons and Meditations on the Art of Conducting, Frank Battisti, Meredith Music Corporation, 2007.

"Do Orchestras Really Need Conductors?", Shankar Vedantam, All Things Considered, National Public Radio, November 27, 2012.

"Frederick Fennell: 'The Civil War: Its Music and Its Sounds', Early Brass Band Podcast

"Frederick Fennell Rehearses Lincolnshire Posy With the U.S. Navy Band", United States Navy Band, DVD, March 24, 2015.

Arturo Toscanini: Contemporary Recollections of the Maestro, B. H. Haggin, Da Capo, 989./p>

"Frederick Fennell Discography", Discogs.

General Register, 1932, University of Michigan.

Ngram Viewer, Google Books.