Frederick Law Olmsted and the Journeys Through the Slave States

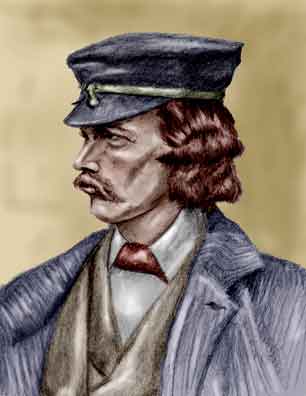

Frederick Law Olmsted

He did a bit more than design Central Park.

Frederick Law Olmsted originally planned to attend Yale, but at age fourteen he contracted a case of sumac poisoning which effected his eyesight. But being from a well-to-do family he did not really have to work for a living and spent - as he put it - a few "vagabond" years traveling about. By his early twenties, Frederick had already traveled in Europe and had signed up on a merchant ship that went to China.

When Frederick returned home, he managed one of the family farms. He did so well that his dad put him in charge of other of the family holdings. After a few years Frederick decided to travel around and study the farming and agricultural methods of other parts of the country. That naturally led him to travels in Deep South about which he sent regular articles to the New York Daily Times.

The Union was falling apart, and slavery was the most important and divisive political issue. The majority of (white) Southerners were adamant to preserve their constitutional right to maintain their "property", and members of the (for the time) radical abolitionist movement were equally adamant to end slavery completely and at once.

But the attitude of most Northerners - and this included Frederick - was much more ambivalent. In general northerners thought that slavery was wrong, but looked on abolitionists as a radical fringe group (even Abraham Lincoln never demanded an absolute end to slavery). If northerners argued against slavery it tended to be along economic lines. The usual arguments were that slavery was inefficient, costly, and it put free laborers out of work. In his private correspondence, Frederick voiced opposition to slavery, but on other hand he conceded his views might very well be wrong and the Southerners might be right.

To history's boon, though, what we see now as Frederick's wishy-washy stance produced descriptions of the South that were about as accurate as you could get. With no particular ax to grind or an opinion as to what was right or wrong, he simply wrote down what he saw and heard. His books, though, which tend to be lighthearted in tone, can't be considered the whole story. Frederick was a tourist, after all, and only rarely saw the more sordid and brutal side of the South's "peculiar institution".

Although historians value Frederick's volumes for their record of life in the ante-bellum South, a good part of the books tell of his day to day search for accommodations and getting from one place to another. This was the era when hotels were mostly luxuries of the cities while smaller country inns were often dirty, crowded, and even dangerous. Instead, it was more common for travelers to stay at private residences and the local citizens of any means usually had a "guest room" to put up the unscheduled visitors. Frederick found that Southern hospitality was not entirely a myth, but there were certainly times Frederick wished there was an inn for him to take his chances with.

Traveling itself was a hit or miss affair. There was some train service between major cities, but the cars were usually crowded, cramped, and poorly ventilated. Frederick found that he preferred a stagecoach even though the passengers sometimes had to get out and help push the vehicle free when they got stuck in the mud. There were always unexpected difficulties. Once Frederick showed up at a stage depot and loaded his luggage. The driver said they wouldn't be leaving for more than an hour so Frederick might want to get his lunch. After being assured the stage would not leave without him, Frederick went into the restaurant de la gare. Of course, he returned to find the stage had departed with the other passengers and his luggage. Fortunately, he was able to make other arrangements and actually caught up with the stage.

In real backwoods areas you had to travel on foot or by horseback. Except for times of bad weather this was the mode that gave Frederick most contact with the people. Typically Frederick would rent or borrow a horse and leave it at a specified farm or commercial stable. Then he would rent another for the next leg of the trip. You would think this would be a risky proposition for the horse owner, but evidently most travelers were an honest lot.

Of course, the main interest of the books, then and now, was their description of life of a slave society. Frederick had little opportunity to speak with many slaves, but on the occasions he did, it was clear the idea of being free was high in the slaves' minds. It is also surprising to see how many of the slave owners also wished the South had never seen slavery. Their complaints, though, mostly dealt with the responsibility of being a master. It was, they said, almost impossible to get the slaves to do any work. You had to be after them all the time, they said, showing them what to do every little step of the way. Why, the slaves feigned sickness, stole anything they could, and by golly, just didn't work they way they should. Of course, what the slave owners were describing - and ignorant of - was what historians refer to as "low level resistance". Knowing a successful escape was virtually impossible and that they had no hope of advancing their lot in life, the slaves took considerable delight in putting it over on their owners.

Very rarely did Frederick encounter the "kind" master of Southern mythology, and he did witness what was no doubt common violence against the slaves. This ranged from the occasional cuff or slap to a brutal whipping of an adolescent girl. The frequency that Frederick reported such abuse was much less than you find in the writings of former slaves themselves such as Frederick Douglass. Part of the discrepancy is that the slaves' narratives naturally focused on the inhumanity of the institution, while as a guest and tourist Frederick was kept apart from the day to day plantation operation. Frederick made few comments beyond reporting the incidents, but we do have to remember that whipping was still more or less standard punishment.

Sometimes Frederick did find some farms or plantations where the atmosphere was considerably laid back. At one farm in Mississippi, the owner actually let the slaves decide what work needed to be done and when and treated them more like hired hands (although without paying them an actually salary). At noon everyone came back to the house, and although the farm owner was served in the dining room and the slaves in the kitchen, they all ate the same food. From the length at which Frederick described this farm and from Frederick's unusual editorializing, what he saw there was clearly not the norm.

One of Frederick's friends was a landscape architect named Andrew Downing. In the early 1850's, they decided to submit a design for the then-proposed Central Park in Manhattan. They won the contract and when Andrew was killed in a ferry boat fire in 1852, Frederick took over the project. He eventually became the New York's Parks' Commissioner (filled later by the illustrious Thomas Hoving), and in addition to Central Park, Frederick and his firm designed the ground of the US Capitol, Washington's National Zoo, various college campuses including Stanford University and the University of Chicago, and the 1893 Columbian Exposition World's Fair in Chicago. And this is just a smattering of what Frederick wrought. Although Frederick died in 1903, his sons continued to run the family firm which was in business until 1980.

References

Although first editions of Frederick's travel books are expensive, these are the ones listed here. Later editions are available in less pricey reprints. All the titles can also be found as online editions, the most convenient (in a CooperToons personal opinion) are viewed at the University of Pennsylvania Online Books website at http://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/. Frederick's books are specifically found at http://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/webbin/book/lookupname?key=Olmsted%2c%20Frederick%20Law%2c%201822-1903.

Walks and Talks of an American Farmer in England, Frederick Law Olmsted, George Putnam, 1852. Frederick's earliest book of an early trip to England with his brother.

A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States, with Remarks on Their Economy, Frederick Law Olmsted, Dix, Edwards, and Company, 1856. Frederick's first book of his travels in the slave states. Selections of this book and from the others listed below were incorporated into the compedium The Cotton Kingdom

In this and subsequent volumes, the modern readers should be avoid being over censorious at Frederick's representation of the slave's speech. Yes, it certainly comes off as condescending, but as did many of the WPA writers in the 1930's when recording the slave narratives, Frederick is making an honest attempt to represent the sound of the dialects. It is ironic, though, that some of the spellings could also fit with mainstream American English. After all, everyone pretty much says "wuz" for "was".

A Journey Through Texas - Or a Saddle Trip on the Southwestern Frontier, Frederick Law Olmsted, Dix, Edwards, and Company, 1857.

A Journey in the Back Country, Frederick Law Olmsted, Mason Brothers, 1860

FrederickLawOlmsted.com (at http://www.fredericklawolmsted.com/). Yes, Frederick has his own website and one of the better designed ones - as we should expect - on the web.