John Philip Sousa

and the

Instrument That Will Forever Bear His Name

|

Big John |

||

We see that John1 didn't give his approbation only to military music. He never limited his repertoire - performing or composing - to marches. A John Philip Sousa concert was a true cornucopia of musical genres.

Footnote

We wonder how the friends of John Philip Sousa addressed him. Some may remember a television show from years ago where John's wife, Jane, called him "Philip" (she also admonished him at one point not to swear). Later the author Alex Haley (of "Roots" fame) writing for a young audience referred to "Philip" during the composer's boyhood. Then there's a newspaper article written during his lifetime that referred to "Philip" Sousa without the "John". So it may very well be that his friends and family called him by his middle name. But we'll be more formal and call him John.

And John, by the way, called Jane "Jennie".

Of course, everyone knows about John's famous quote, "Jazz will endure just as long as people hear it with their feet instead of their brains". Or something like that. Unfortunately as much as you see the quote plastered around, you'll never see an actual source, and an academic biography doesn't mention the quote at all. But that John said something like that is likely and the quote began appearing when John was still alive.

In fact, early on John thought jazz stunk and that it would eventually die out. But as time rolled on he realized people liked the hip cool tunes and he would feature jazz, or at least ragtime, in his concerts.

But still we have to be honest. If there's anything that people remember about John Philip Sousa, it's his marches.

Oh, yes. And one other thing.

The true JPS cognoscenti will remember him as the inventor of the instrument known as the sousaphone. That's the type of tuba that the players loop on their shoulders, all the more suitable for marching.

But of course, we said that's what people remember John for. It doesn't mean that it's true.

Instead the consensus of musical historians tends toward the sousaphone being built by J. W. Pepper, an instrument maker and publisher from the Town That Snowballed Santa Claus. Of course, if John had described the type of instrument he wanted in sufficient detail, he could legitimately be considered an inventor or at least a co-inventor. But other scholars say it was really J. W. who made the suggestion for the redesign. For his part John was a big tuba fan, and he predicted eventually every household would have one.

Rain Catcher

Not exactly what we see today.

But whoever invented it or set one up in their front parlor, the original sousaphone was not exactly what we see today. The early instrument had a bell that pointed up - and so it was sometimes dubbed the "rain catcher". It really looked strange, and it wasn't until 1908 that the instrument as we know it - with the bell facing forward - was put on the market.

In fact, the modern sousaphone is less a rebending of the upright orchestral tuba than a further development of the helicon. The helicon was invented around 1845 (nine years before John was born), and was for all practical purposes, a sousaphone, albeit with smaller bore (tubing diameter) and bell (the flared opening where the music comes out). Although the helicon bell can't be reoriented (as can that of the modern sousaphone), it is directed more like the modern instrument although more upward and to the side. But if you see a helicon you'll recognize it as a sousaphone.

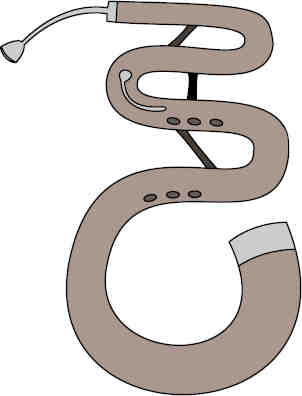

The Serpent

The sousaphone and the upright tuba were actually parallel developments and the common ancestor seems to be the serpent - a convoluted and strange looking deep sounding instrument which looks incredibly difficult to hold. Instead of having valves, the notes were sounded by stopping holes along the tube. Later padded keys somewhat like those of the modern clarinet and saxophone were added. The mouthpiece, though, was that of a brass instrument.

The serpent soon evolved into the ophcleide which looks more like a modern orchestral instrument. It, too, had woodwind-like keys, and resembled a gigantic saxophone. However, like the serpent, the ophcleide had a metal cup mouthpiece rather than a reed. Adolphe Sax, who invented the saxophone, deliberately borrowed the ophcleide's design for his new fangled instrument.

The ophcleide came in different sizes, and some had more of the range of the modern euphonium or baritone horn - essentially that of the trombone. All in all the pitch wasn't that low. Still Giuseppe Verdi liked the ominous sound and stipulated the instrument for the Dies Irae section of his Requiem.

Adolphe, though, was intimately involved in the development of the modern tuba with his production of the saxhorn. The saxhorn has the basic design of an upright tuba, and like the ophcleide, it came in various sizes. Because of their ruggedness and low maintenance requirements, the saxhorns became a staple in the brass bands of the 19th century, particularly during the American Civil War. During a march, the instruments leaned back over the left shoulder where the sound could be directed behind the player. That way the soldiers behind the band could hear the music and keep in step.

The Modern Instrument

The saxhorns probably had more variation in size than any other instrument family, the violin and string bass possibly excepted. Some were trumpet size (the flugelhorn) and others were like the euphonium and baritone horn of today. The largest saxhorns were recognizably the modern upright tuba and had a similar range.

The word tuba, though, is what the Romans used for what we'd call a "natural" trumpet and was a straight non-valved instrument. On the other hand the Romans also had brass instruments that curved around the shoulder. One instrument was the cornu (literally, horn). The cornu's deportment has a noticeable resemblance to the helicon and hence the sousaphone. Another instrument which to layman's eyes looks much the same as the cornua was the buccina. Like the Roman tuba, the cornua and buccina had no valves.

Roman Cornu

(Or is it a buccina?)

Ancient brass instruments are the easiest to recreate and so we have a pretty good idea how they sounded. Reconstructed cornus - actually the plural is cornua - aren't that pleasant and sound rather harsh and out of tune. But pleasant notes really weren't needed as the cornu and straight trumpet were mainly used for issuing signals in the military. But you can also see them being played during festivals and games and with other instruments.

We know quite a bit about other Roman musical instruments. In addition to the tuba, cornu, and buccina, they had the tibia (a double recorder), panpipes, lyres and harps, lutes, the kithara (a type of zither), drums and other percussion instruments, and - a bit of a surprise - the pipe organ. The Roman instrument was a "water" organ - called the hydraulis - and had the air fed in to the pipes by water pressure. The hydraulis was being used as early as 250 BCE well before the bellows organ which was invented about 700 years later.

As much as we know about the musical instruments of the Romans, we know relatively little about the music itself. Most likely it was divvied up into two general areas. Part they borrowed from the Greeks. We're pretty familiar with Greek music since they left a lot of writing about it, including their notation. Our modern keys and modes are pretty much what the Romans got from the Greeks.

The other area of Roman music is that which was indigenous to the Italian peninsula. Certainly the Etruscans had their own music which must have been a major influence. But as for what the tunes were like in Rome and what the music actually sounded like, we have scant knowledge.

But as for the life and music of John Philip Sousa, we're well informed. Everyone knows John was in the Marines but not that he served in two separate stints. The first tour of duty was from 1868 to 1875 when he was a musician in the band, a span of years beginning when at age 13 he began his "apprenticeship". He also wrote his first march "Salutation" during that first interval and as you might expect it's not bad but not quite his best. Then at age 20 he left the service and spent the next several years working in the music industry. He wrote songs and arrangements for various publishers and played in and conducted bands and orchestras. Although the violin was his principal instrument, he could pretty much play whatever was needed

By 1880 John had become well enough known that he rejoined the service specifically to lead the band. Under his baton the Marine Corps Band became one of the biggest attractions for concerts and parades. By the 1890's, John was arguably the #1 celebrity in the United States.

Then after twelve years and at the suggestion of impresario David Blakey, John decided to form his own band. So he left the Marines in 1892. With no restrictions on the concerts or the tours2, the Sousa Band became more popular than ever. John also made sure he had top musicians3.

Footnote

In his first years as the director of the Marine Band, John had problems getting approval for going on tour as one of his superior officers thought entertaining the public wasn't what the band was there for. After the officer left the service, John discreetly asked the First Lady, Caroline Harrison, if she could get her husband's feeling on the matter. Mrs. Harrison's intervention was successful and the President approved the band going on tour.

Footnote

Some of the musicians were virtuosi even by today's exacting standards. One of the premier players was trombonist Arthur Pryor. He was a frequent soloist and his variations on the "Bluebells of Scotland" remains one of the show tunes in the trombone repertory.

If you read what John said in interviews, you might think the band was international in its diversity since he said he had a large number of German musicians. However, this was a time when people still thought ethnically. So even if someone was born in America (and so was a US citizen), they might still refer to themselves as Irish, Italian, or German4.

Footnote

Although it's a novel, Studs Lonigan by James T. Farrell gives a good representation of the way Americans could identify themselves with the country of their families' ancestry. Set in the 1920's in one chapter Studs and his friend, Les Doyle, decide to join the YMCA so they could use the gym and swimming pool (Studs had been worrying that he was getting an "alderman"). At the Y, the membership officer took down their information.

"You're Christians I assume?"

"Irish", said Les.

John's new band was popular from the first and toured the United States and Europe. But he wasn't one to get into a rut and in 1896 he produced his first operetta, El Capitan which featured the march of the same name. All in all John wrote 11 operettas and at one time he had three of them playing on Broadway at the same time.

When the Spanish American War was declared, John offered to re-enlist. However, there weren't really places where he would fit in (the Marine Band already had a conductor). He also really needed a rest as his constant touring had pushed him to the point of collapse. The war, though, was brief and was over in a few months.

In 1910 John came down with malaria, but even that scarcely phased him. When he got out of the hospital, he and the band began a world tour. They played in Montreal and then headed off to the British Isles, the Canary Islands, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Fiji, and Hawaii, then back to Canada and the US. They ended up in New York on December 9, 1911.

Of course, then came World War I. John was able to join the Navy and he conducted the Navy Band at the Great Lakes Station. He continued to write marches including "The United States Field Artillery" better known as "The Caissons Go Rolling Along". But none of his marches caught the public's attention like George M. Cohan's "Over There".

After the War, John began to slow down a bit, and the band didn't leave the US except for a couple of short tours in Cuba and Canada. John no longer wrote operettas and instead focused on new marches. Probably the top three after 1920 were "The Gallant Seventh", "The Black Horse Troop", and the always popular "Nobles of the Mystic Shrine" (yes, John was a Shriner).

As 1932 came in, John was 77 and still going. On Friday, March 3, he arrived at Reading, Pennsylvania, to conduct the Ringgold Band for a concert the following Sunday. On Saturday he rehearsed the band and afterwards was the guest at the inevitable banquet. Although he seemed tired, he gave a speech which everyone enjoyed. He then returned to his room at the Abraham Lincoln Hotel where at 1:30 a. m. he died of a heart attack.

Footnote

The Abraham Lincoln Hotel is still there and on the outside looking much like it did during John's time. However, the back part was later torn down and the current building isn't quite as thick as it was.

And the last song he had rehearsed? Well, what else? "The Stars and Stripes Forever."

References

"New Ragtime Studio Opens in Washington", The Washington Times, January 27, 1921, p. 8.

The Independent, Vol. 121, 1928, p.120.

"John Philip Sousa: American Phenomenon", Paul Bierley, Integrity Press, 1986.

"John Philip Sousa", Paul Bierley, Library of Congress.

"John Philip Sousa", Encyclopedia Britannica.

"Biography of the March King: John Philip Sousa", Public Broadcasting Service.

"John Philip Sousa", Alex Haley, Boys Life, July 1966.

"John Philip Sousa's Other Music", Emily Reese, Classical MPR, June 29, 2015.

"John Philip Sousa, a Descriptive Catalog of His Work", Paul Bierley, University of Illinois Press.

"Francesco Fanciulli", Colonel Jason Fettig, Director, The President's Own, United States Marine Corps.

The History of the Tuba", Greg Monks, Alan David Perkins, Black Diamond Brass.

"History and Origin of the Sousaphone", Sousaphone.

"Two minutes on...the Ophicleide", John Elliot, Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment.

"Ancient Roman Musical Instruments", Educational Technology Clearinghouse, Florida Center for Instructional Technology, College of Education, University of South Florida.