Josef Stalin: Pioneering Meteorologist

(Among Other Things)

Иосиф Виссарионович Джугашвили

Uncle Joe Steel

On March 6, 1953, a young Romanian schoolgirl came home in tears. While she was at her studies, she and her schoolmates and teachers had been suddenly summoned to the auditorium. There the headmaster stood on the stage and gently but sadly broke the news. The leader of the Soviet Union and its allied countries for nearly thirty years, the man who by sheer intelligence and force of character had led the troops to victory in the recent World War and who had singlehandedly transformed a backwards collection of disparate agricultural countries into a unified major industrial world power, and who as a young man had helped throw off one of the last vestiges of the royal despotism had passed away the night before. Yes, Iósif Vissariónovich Stalin was no more! All of the children were devastated although when the girl told the story fifty years later, she was laughing about it.

Iósif Vissariónovich Dzhugashvili was born on December 6, 1878 in Georgia - not the US state but the small country in the Caucasus Mountains immediately east to the Black Sea. However, the calendar in Russia at that time was based on the old Julian Calendar and when you correct for the Gregorian calendar that comes out more like December 18. Later Iósif subtracted a year from his age and that date is still found a lot both in books and on the Fount of All Knowledge.

Iósif's dad, Besarion, was a shoemaker who had set up a moderately prosperous business. He was also a first class boozer and sukin syn who would beat his wife and kids whenever he felt like it. It is, of course, common to point out how Besarion's brutality must have adversely affected the personality development of young Beso (as Iósif was called in his early years). But you also suspect that young Iósif would have been a sukin syn no matter what.

With the exception of his youngest daughter, Svetlana, Iósif, with whom he had a distantly affectionate relationship, he was at best totally indifferent and often completely brutal to his own children and wives. Because Iósif was so hateful to his oldest son, Yakov Dzhugashvili, the young man tried to kill himself (but failed) and later died as a prisoner of war in Germany after his father refused an offer for a prisoner exchange. And in 1932, Iósif's second wife, Nadezhda Alliluyeva, after a night after being completely ignored and even taunted by Iósif at a state function, went back to her room and shot herself.

At the same time we have to admit that Iósif did have a good education. He also had some literary talent and had some poetry published in his native Georgian when he was a young man. But he could pretty childish and enjoyed coarse jokes at other's expense. His favorite expression was - as author Ian Fleming described the phrase - a "gross obscenity" which was written by Ian as "Y** t**** mat!" But then, a lot of other Russians say that too. No joke, Sherlock.

Young Iósif's horrible family life was a bit mitigated by the fact his dad eventually left home and that his mother made sure Iósif was able to enter the Theological Seminary in Tiflis, the Georgian capital. Iósif appears to have completed most of his studies but didn't officially graduate for reasons which are a bit obscure.

That is the reasons are a bit obscure not entirely obscure. By his last year in the seminary - around 1899 - he had become a devotee of the latest fad amongst the young eggheads in Tsarist Russia. That was the philosophy of Karl Marx who, among other things, derided religion as the opium of the masses. Karl also advocated true revolution as the way to improve what had become deteriorating conditions for the increasingly numerous poor throughout Europe. Various workers revolts in the mid-19th century, including the formation of the Paris Commune, seemed strong enough evidence that Karl really knew what he was talking about. So Iósif became a committed believer, not only in Karl's writings, but in those of the Russian Marxist writer, Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov.

Vladimir was eight years Iósif's senior and was no stranger to revolution. His older brother, Alexandr (a transcription of the Russian spelling, not a misprint), had been arrested, convicted, and executed for plotting to kill the Tsar, Alexander III. Lamentably this was not, strictly speaking, a miscarriage of justice. Alexandr was a science student at the University of Petrograd where he and a number of other students had indeed constructed a bomb they intended to toss at the Alexander as he drove by. Somehow the plot was found out and the students arrested. Five of them, including, Alexandr, were executed on May 8, 1887. At the time, Vladimir was only 17.

Vladimir followed his brother's footsteps as a revolutionary although in a more cerebral, not active, manner. Soon he was writing articles and pamphlets espousing the Marxist polemics. Even this, though, was not a safe activity in any country, and in 1895, Vladimir found himself arrested and exiled to Siberia.

At this point we need to pause and point out that the new Tsar, Nicholas II, was not a very good despot. The second cousin and spitting image of King George V of England, Nicholas wanted to be an absolute autocrat. But he was also a bit of a sissy when it came to dealing with revolutionaries. Unless they were actually carrying out violent revolt - and sometimes even then - he just sent them into what is called "internal exile".

Now "exile" was not quite what you think. Nicholas's exiles were usually put on a fairly comfortable train with a couple of guards and then sent to some provincial town of reasonable size. It could be, but was not always, in Siberia. But wherever they were sent, they would spend their time, reading, writing, and taking it easy, all at government expense. They lived among the local population, socializing at the taverns, and at times making whoopee with the local country girls. When they got tired of exile, they hopped a train and just went back to Moscow, St. Petersburg, or wherever they wanted to go until they were re-arrested and sent back. Vladimir himself finally tired of exile and left for Europe. Iósif - or Joseph to use the Anglicized spelling - himself was arrested for his revolutionary advocacy and exiled a total of seven times, during which he generally had a good time.

In Europe, Vladimir continued to used his considerable forensic and writing skills to become the leader of the Social Democratic Labor Party which advocated a monarch-free Russia. But after a disagreement with his fellow SDLP member, Julius Martov, in 1903, Vladimir split off with a group that became known as the Bolsheviks - roughly meaning "majority". By then Vladimir adopted a macho he-man nom de reévolution, guerre et plume, Lenin, whose actual meaning is a bit obscure.

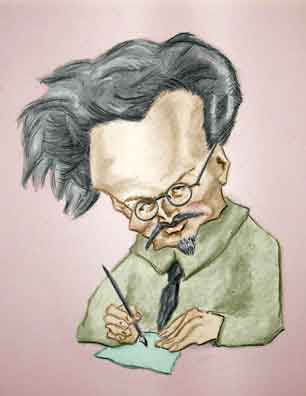

It's sometimes been pointed out that an increasing number of modern politicians never have what you call a "grown-up" job. Instead, after college they attach themselves as interns to some successful politician or have their rich pappies set them up in some business that loses money until they can worm their way into the political system. We hardly need point out that this is nothing new and is sort of what happened with Joseph. As far as the records show, the only real job he ever had was briefly working as a weatherman at the Tiflis Meterological Institute around 1900. But he soon chucked the weatherman's job to actively join the Russian revolutionaries who by now were supporting themselves by "heists", chiefly robbing banks, a revolutionary activity that was also at this time being practiced Joe's contemporary Pancho Villa.

Of course, all good revolutionaries are supposed to divert their booty for financing the revolution. But of course some also had to go for what George Washington, another successful revolutionary, called "necessary expenses". For George "necessary expenses" meant spending $6000 in wine for just one six month period. For Joseph the expenses went at least in part for a near constant supply of the strong Russian cardboard tipped cigarettes, a steady flow of the domestic vodka and wines, not to mention money for attending international Marxist conferences which were cropping up in England, Finland, and Sweden.

It was at these conferences that Joseph finally met Lenin. Lenin had read some of Joseph's own writings and thought they were "perfect", an opinion that made Joseph really wag his tail. Soon Joseph was part of Vladimir's inner circle of serious revolutionaries.

Of course, a bunch of twenty-somethings (although Vladimir was in his thirties) playing at revolution isn't going to bring about much change. That requires serious discontent among the population. Things were indeed getting unpleasant in Russia with its horrible working conditions in factories and frequent food shortages. Workers started striking and riots broke out in a number of cities. The Tsar sent in the soldiers and a number of the citizens were killed. But after the defeat of the Russians in the Russo-Japanese War, divisions of the Imperial Army itself mutinied, and by October 1905 the country was at a standstill. The Tsar finally acknowledged there were problems and promised to liberalize the country. He allowed political parties and freedom of expression, and he even let set up a parliament called the Duma. Although Nicholas still retained ultimate power, the popular fervor for revolution abated. The Bolsheviks, though, wanted the Tsar out and kept up their agitation which included assassination of their opponents.

So things continued until World War I. Nicholas, supporting his English cousin George, (who had doubts about Nicholas's ability), declared War on Germany and ordered the Russian armies into battle, virtually all of which the Russians lost. Hundreds of thousands of soldiers - some say more than a million - died. Soon battalions refused to obey their officers and in the cities new food shortages got so bad that again riots broke out throughout the country. In February 1917 the Duma established a provisional government with Alexander Kerensky as Prime Minister. In September, Alexander declared Russia was a republic.

Lenin left Europe and returned to Petrograd in April 1917, which made some great paintings. Alexander, as prime minister was still fighting the Germans, and possibly borrowed an idea from the American Revolution when he encouraged the creation of armed citizen militias. But a good chunk of the militias threw their support to Lenin.

By mid-1917 no one in Russia knew who was really in charge. In fact, the country was in a state of anarchy. Officers loyal to the Tsar were soon deposed - and some shot - by their soldiers. By late October, St. Petersburg - now renamed Petrograd - was in the hand of the Bolsheviks except for a contingent of soldiers who were guarding the Winter Palace where the Tsar and his family lived.

On October 25, Lenin issued a proclamation that the old government was ended and the Bolsheviks were in charge. Two days later, October 27,the younger brother of the Nicholas, Michael, who held the position of Grand Marshal, wanted to avoid any confrontation where soldiers of the Tsar would fire on the crowds. So he ordered the guards away from the Palace. Although laudable in intent, the effects were as expected. The palace was then stormed by the Bolshevik's who took the Tsar and his family prisoner. They were moved around to various locations and finally imprisoned at Yekaterinburg in the Ural Mountains at the home of local merchant that had been enclosed in a wooden palisade. There sometime around midnight July 16, 1918, the Tsar and his family were woken up and told they were to be moved to a new location. They were herded into the basement where around 2:30 on July 17, everyone in the family was shot. One of the family dogs, though, was spared and somehow ended up being sent to Nicholas's cousin in England and was kept at Windsor Castle.

After the Romanov's murder, a horrible (and in the United States little known) "White vs. Red" civil war (i. e., Kerensky vs. Lenin) ensued for five years. The Bolsheviks finally emerged as victors in October 1922. Alexander Kerensky escaped and eventually moved to the United States where he became - this is true - a member of the Hoover Institute Think Tank. He lived until 1970.

With the victory of the Bolsheviks, everyone - or at least the Bolsheviks - believed everything would settle down into one happy proletariat paradise with everyone skipping merrily to man the barricades. Fat chance. There were a considerable number of factions who fought with the Bolsheviks and now wanted a piece of the revolutionary pie. One of the non-Bolshevik groups were the Socialist Revolutionaries.

Dmitri Shostakovich

He talked with Josef

During all this time Joseph was literally by Lenin's side. While able men such as Mikhail Tukhachevsky - later a friend and patron of the young composer Dmitri Shostakovich - led the Red Army against the White Russians, the political types - Lenin, Stalin, and newspaper editor Leon Trotsky - spent their time in Moscow safely away from the fighting. In an interesting aside, out of these three men, only Joseph was limited to speaking in Russian and his native Georgian. Both Lenin and Trotsky spoke a number of European languages, including English.

Vladimir himself lasted only two more years and died following a number of strokes on January 21, 1924. His premature demise was probably hastened by his being shot in the neck and shoulder on August 30 by a would-be assassin, a young lady named Fanya Kaplan who was indeed a Socialist Revolutionary. She said she considered Vladimir a traitor to the Revolution because of his movement of Marxism toward dictatorship (even Marx was supposed to have said he was not a Marxist). The attempted assassination was all the ammunition - no joke intended - that the Bolshevik's needed. Joseph, who had more or less been hand picked by Vladimir as his heir apparent, began to take charge.

Leon Trotsky

He left for Mexico.

Still it's not quite true, as you may read on the Fount of All Knowledge, that Joseph became dictator of the Soviet Union right after Lenin died. Yes, he was given the title of General Secretary of the Soviet Union immediately after Lenin was shot. But the government of the Soviet Union was always more complex than often pictured in America. For about five years Joseph had to share power with other party leaders. There was much infighting and a lot of the politicians didn't like each other very much. But then Joseph got an idea that ultimately put him in charge.

When he won the Civil War, Lenin had made changes in the Russian economy which included, among other things, strict wage and price controls, something the US President Richard Nixon had also tried out in the early 1970's with indifferent success. However, Lenin's new rules did permit small businesses to retain profits as an incentive for better production. However, in 1928, there were major grain shortages in the cities. Joseph had the idea that the small farmers - whom he derisively called kulaks (literally "fists", i. e., "tightwads") - were keeping back part of their harvest so that the price of grain would rise. Joseph then went to Siberia to check things out himself.

The War Against the Kulaks marked the beginning of Stalin's business plan to produce a Russia that would do a hey-presto! change from a country full of repressed and downtrodden peasants to a fully modernized industrialized state populated by happy workers laboring contentedly during the day and going home at night to warm, happy homes where at their generous but not ostentatious dinners during which they would all drink vodka toasts to their benevolent Father Joseph Vissarionovich. But you could not, Joseph thought, put such a grand scheme into action unless the people were 100 % behind the government and not working for their own self-centered profits. So he decided the ability of small businessmen - whether agricultural or manufacture - to keep profits must be eliminated.

Joe's heavy handed techniques, though, were not approved by all. Remember, Joseph did not "seize" power. He eased himself into it over a period of years. And although Trotsky had been banished from the party and exiled from Russia entirely (eventually settling in and being assassinated in Mexico), Joseph still had his opponents. When he returned from his first kulak-bashing trip, the then Soviet Premier, Alexei Rykov, threatened him with criminal charges for effectively stealing grain from the farmers. But Joseph's buddies in the Politburo - the group of top level politicians that largely controlled the country - outnumbered Alexei and his friends, and the forced collection of grain continued.

By 1930, Alexi had been booted from the Politburo which was now populated almost exclusively with Joseph's flunkies. This made it pretty easy to draw up an official plan for exterminating the kulaks altogether. At this point we need to point out that Joseph's overall strategy - with modifications - has now become a model for handling political problems pretty much everywhere. If things go wrong, find someone to blame.

But Joseph's modus is not, thankfully, used in all countries. And when he said he would exterminate the kulaks, it did not necessarily mean he kill the individuals. It was the class that would be destroyed. So each year Joseph sent the army in to seize the grain and arrest any farmers who were a bit too prosperous. "Too prosperous" generally meant they owned a couple of horses and were able to hire one or two workers. Now if the authorities decided the well-to-do farmers were simply ill-advised and had erred through no fault of their own, they would just seize the land and make it part of the new state corporate farms. The former kulak would then go to work as a laborer, possibly on what had been his own land. But if the authorities thought the kulak was a deliberate "enemy of the people", they was shipped him off to exile, execution, or both.

But as Joseph himself knew full well, exile under the Tsar's had been a bit too cushy. So now the government began constructing huge labor camps whose inmates, among other things, provided timber and minerals for the burgeoning Soviet lumber and steel industry. Some sources state at one point the Russian prisons and camps held more than a quarter of the total population although this seems a bit high.

The labor camps had a strange official invisibility until the publication - ironically in the Soviet Union - of One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovitch by Alexander Solschenizyn in 1962. Alexander's novel is a description of a routine day in a camp - which Alexander had experienced first hand - as seen through the eyes of one of the prisoners. It is interesting to compare that novel to the actual memoir of Haywood Patterson, who had been a black inmate of a southern penitentiary in the United States. Honesty compels the reader to say Heywood had a worse time. This is not to say the labor camps were a great place to be.

But what did the average Russian think about Vladimir and Joseph and the others? Well, as in most revolutions, some people were for it, and some were agin' it. Naturally the independent farmers and business owners, finding their property seized and themselves perhaps imprisoned if they were lucky, were opposed to the changes. Some actually resisted, which gave Joseph even more ammunition (literally) to accelerate the program. However, the poor agricultural workers who had to go on tilling the land of someone else using centuries old farm tools were by no means opposed to the changes. They now found themselves working with modern mechanical equipment and for wages which were higher than their former employers had been willing to pay. For them, the revolution was a good thing - for a little while.

Unfortunately, as businessmen say today, Joseph's plan did not meet the projected expectations. Shortages of food and manufactured goods continued and Joseph as always blamed on someone else. If anything went wrong, then "enemies of the state" were hoarding the products of bumper productivity which he knew the collective farms and government run industries were actually producing. Naturally he had - quote - "proof" - unquote - for what he said.

One of Joseph's characteristics - admittedly shared by many in our own time - was the inability to distinguish between what existed in the real world and what he saw in the movies. In the late 1930's motion pictures had become one of the most popular forms of entertainment and was also beginning to emerge as the preferred method of spreading information. Joseph wanted to show the rest of his country and the world how great the new collective farms and industries were doing. So he sent film crews out to the farms and factories. When the movies were distributed everyone got to see healthy happy farm and factor workers smiling as they produced more crops and goods than any other country in the world.

So if some officials came up to report the food and goods shortages were due to bad harvests or from supply and equipment problems, Joseph would bellow what poor year? What productivity problems? Why, y** t**** mat! look at the movies, he would say pointing to his own propaganda films. There the farms are producing bumper crops, and the steel mills have reached world record productivity. So Joseph concluded the real problem was the whining bureaucrats were deliberately covering up misappropriation and corruption. So the labor camps which had originally been filled with the small farmers and merchants now began to receive government officials and factory managers. From then on there was never a lack of supply for the camps.

(For what it's worth, everyone was expected to chip in long after Joseph's time. In the 1970's, a physics professor from Purdue was part of a scientific exchange program at Chernogolovka, the science town near Moscow. One day the members of the physics institute had to go out and help harvest potatoes on the near-by collective farm. The American professor went along - voluntarily - and he said it was really rather fun. They easily made their quota and had enough time left over for a potato roast and football (soccer) game afterwards. His Russian friends did tell him, though, that harvesting potatoes when it was cold and raining was not much fun.)

But by the late 1930's, things had not gotten any better. So Joseph needed to keep looking for people to blame, and like any good manager, he was convinced anything that had gone wrong couldn't be his fault. So he kept reorganizing the country and replacing his underlings who he felt were screwing up. That was fairly easy to do since in a country as large and sparsely populated as Russia, it was no problem to build more labor camps. But by the mid-1930's so many people had been reorganized and replaced, it was hard to find anyone else in the Politburo or Congress of Soviets to reorganize and replace.

So in 1936, Joseph began what is called the Great Purge. This not only involved wiping out a good chunk of the army officers whom he suspected - probably correctly - of wanting to stage a coup - but created a country where anyone could tattle on someone else. If you wanted to rat on someone, why you could just write Joseph a letter about someone you suspected of being an enemy of the state. As like as not, the person would be arrested and you'd never see him or her again. It was a time not much different than the Terror of the French Revolution. Neighbor turned in neighbor, worker turned in boss, and - literally - kids turned in their parents.

Boris Pasternak

Josef would consult.

Exactly how many people Uncle Joe killed is a difficult question to answer and depends what you exactly mean. Numbers as high as 60 to 70 million have been cited as well as numbers as low as 700,000. The high figures don't usually mean these are people Joseph personally ordered to be executed. If that were the case, Joe would have had to sit down at his desk in 1922 and spend the rest of his life 24/7 signing one death warrant every 15 seconds. Instead, the high numbers usually include the people who died in the prison camps and from famines, like that in the Ukraine in 1933 which directly resulted from the war on the kulaks and so, yes, were Joseph's fault. However, some historians from reviewing the recently opened archives - while realizing they may have been sanitized by Joseph's successors to protect themselves - revise the figures down a bit. But not that much. The official Russian records - which certainly have their flaws - indicate that a total of 19 million died as a combination of outright executions, death under torture, famine, and death in the labor camps.

The lower number, though, is still high and we're talking 15 - 20 % of the population. People who survived the era began speaking more freely in the 1990's and mentioned that co-workers, fellow students, and neighbors (including whole families) completely disappeared.

How many executions did Joseph personally approve? Historians have found 44,000 names in 336 lists that were personally signed by Joseph himself. We have no idea if there are other lists that were lost or destroyed. That's a lot of names but no where near 20 million. But Stalin didn't have to make the lists themselves. People who were in the bureacracy stated that Stalin actually set quotas for each district that so many people had to be sent to the labor camps and so many had to be executed.

Once arrested, as the records of the secret police (whether the Cheka, OGPU, or NKVD) show, many people readily - quote - "confessed" - unquote. Joseph knew that the victims were not really guilty and even laughed about how easily his police could worm out confessions. Although some confessions were prepared in advance, others were just the results of "physical pressure" (as the records called it). The "physical pressure" was pretty rudimentary and low tech. Beating with truncheons was the preferred method but what are now called "enhanced interrogation techniques" like sleep deprivation were also popular. But in the rare occasions when a confession was not forthcoming it really didn't matter. A speedy trial - some as quick as five minutes - were sure to render justice in Joseph's eyes.

In many cases, though, the physical aspect wasn't needed. One of the most effective tools was using threats, not against the people being interrogated, but against their family. This is best illustrated in seeing how Joseph dealt with perhaps one of the most famous of Russian composers and arguably the last of the true classic composers, Dmitri Shostakovich.

Dmitri had achieved near instantaneous fame when he graduated from the Leningrad Conservatory with his First Symphony, and in 1934 had just written an opera called Lady Macbeth of Minsk. Based on a story of one of Russia's favorite authors, the show was a hit from the first with rave reviews in the press and public alike. This supported Dmitri's contention that the work was in full accord with Soviet artistic guidelines since it showed how women could be victimized by the brutal male-dominated culture of Tsarist Russia. In the course of the opera, Katerina Izmailova ("The Lady Macbeth" of "The Lady Macbeth of Minsk") killed off off her husband, her father-in-law, and her husband's cousin in short order, all to the accompaniment of heaving pounding music which fit one scene perfectly when Katerina and her partner in crime, a husky hired hand named Sergei, made whoopee beneath a canopied bed. This was not an opera of traditional Russian Family Values, let me tell you. But the opera was extremely popular both in Russia and abroad. It had gone through 200 performances and Shostakovich, just turning thirty, was an hailed as an international musical genius.

Then in 1936, Joseph went to see it. He hated it.

Oops.

Without doubt one of the most famous articles in the history of music was the Russian newspaper Pravda's review of "Lady MacBeth of Minsk". It appeared on January 28, 1936 . Titled "Chaos [or Muddle], Not Music", and some - probably most - historians have attributed the article to Stalin himself. That's certainly possible, as the tone does have the charming lighthearted touch of Uncle Joe, particularly about halfway through the article where the author (whoever it was) warns "this may end very badly". Then ten days later Dmitri's ballet "The Limpid Steam" was similarly trashed and one of the librettists, Adrian Piotrovsky, was actually arrested and shot.

Shostakovich himself, although he was so afraid he would be arrested he kept a suitcase packed with sundry items and was reported to have been interrogated by the NKVD, was never personally threatened. For some reason, Joseph used his alternative "pressure method" on Dmitri. His sister, Maria, his mother-in-law Sofia Varzar (mother of his first wife, Nina), brother-in-law Vsevolod Frederiks, and an uncle, Maxim Kostrikin were arrested and imprisoned. Vsevolod actually died in exile, and of course, all charges were completely bogus.

Igor Stravinsky

He got out.

It's hard to believe that a man who ordered the murders of millions wasn't crazy. But Joseph was probably not actually psychotic in the medical sense. On the other hand we can be confident that had he been evaluated using modern psychological tests, he would have scored sufficiently high to be diagnosed with what they call a severe psychopathic personality disorder. This simply means - quite frankly - that he was a flaming arsehole, totally self-centered with delusions of grandeur, and was a ruthless exploiter with no concern for others. Add those characteristics with the resources of a terroristic police state and you have one of the worst mass murderers in history.

Maria Yudina

Josef's Favorite Pianist.

On the surface, there was no rhyme nor reason as to who Joseph targeted for denunciation and who he let get away with something that would have been an automatic death sentence in someone else. His favorite pianist was Maria Yudina, to whom Joseph (supposedly) once sent a generous number of rubles after hearing her play. Yudina (also supposedly) replied with a note thanking him and saying she prayed to God to forgive him for his unspeakable crimes (Maria was a devout member of the Russian Orthodox Church). Joseph did nothing and (once more as the story goes) after he died one of Maria's recordings was found on his phonograph. Other famous musicians also fared poorly under Stalin but managed to survive. Of course, Igor Stravinsky had gotten out of the country while the getting was good, but the Armenian composer Aram Khachaturian and the cellist Mitslav Rastropovich suffered through but nonetheless lived through the worst Joseph could offer. But as we'll see later, Sergei Prokofiev, the composer of Peter and the Wolf, did not.

Oddly enough, during the Second World War some things actually got better, mainly because Joseph realized they had defeat to Germany. You could not terrorize the majority of your citizens if you expected them to fight for their country. However, after the war, things went back to, if not quite as bad as during the Great Purge, then pretty close to it. Tens of thousands of Russian soldiers who had been POW's in Germany returned and were then sent to Siberia or executed since they were suspected of collaboration. Still, things began to improve for the average Russian toward the late 1940's.

It is easy to be condescending about how the Russians were completely taken in by Uncle Joe's smaltz. How in the world, we ask, could people could be so naive, and idolize a mass murderer who was sending their friends, neighbors, and family to labor camps (and that was being nice)? But take a look at various articles about Joseph published in the United States during or just after World War II. You read about a firm and reasonable statesman leading his country against the Axis Menace. An article in one of the most popular American magazines of the 20th century pictures a Benign Uncle Joe who is an avid reader, who will give constructive criticism to established Soviet authors as well as "rescuing" deserving but obscure books from oblivion. We read of a highly intelligent leader whose decisive action revolutionized the economy and built up morale in the country. We learn he was a man who wanted peace and would live to see his dream of a Russia raised above its backward roots and serve a - and we quote the article "the shining example for others to follow".

Remember, folks, this was from one of the most widely circulated mainstream American, that's American publications in history. And yet within five years, if Americans expressed agreement with the sentiments of article, they might find themselves out of work, blacklisted, and even arrested. Many did.

Aram Khachaturain

He ran afoul of Josef.

By then Joseph was running the country literally from the dinner table. On a usual day he would get up around noon. He would pass word to his body guards that he was up and they should bring him his morning cup of tea. Then he would examine state papers and deal with matters of the day until early evening. When the work was done, he might go to see a ballet or play. But he had also become a fan of the cinema and would often have screenings of films - Russian and foreign - watching the shows along with the rest of the Politburo. He liked westerns and comedies, but one thing he despised, though, were movies with risque plots.

After the show Joseph and his closest buddies - by then comprising of Lavrenty Beria, Nikita Khrushchev, Georgy Malenkov, Vyacheslav Molotov, and Nikolai Bulganin would go to dinner often at Joseph's Kremlin apartment. At Joseph's insistence, they fueled their meal with copious amounts of wine and vodka, starting off with various toasts and as the night drew on the started into drinking games. They would make their way through so much food - Joseph particularly liked dishes from his native Georgia - that it's no surprise that even the slimmest acquired a bit of a pudgy look. Finally around 4 or 5 a. m., they would begin to wind their way back to their apartments. Supposedly during the night they took some time to discuss business matters but from the descriptions of the servers and guards (and some of the diners), the episodes come off a Friday night for six frat boys who couldn't get a date.

Mitslav Rastropovich

Definitely NOT Josef's favorite cellist.

By the early 1950's, though, the farms and factories were still not producing what Joseph thought they should. So another purge was in order. By late April 1953, he had begun rounding up some leading Soviet physicians, who were largely Jewish, for plotting to kill him and other Politburo members. Needless to say the charges were nonsense, but as usual, confessions were soon forthcoming. The trials were scheduled to begin mid-March.

On March 1, 1953, the usual gang met for dinner, not in the Kremlin, but in Joseph's private residence in Kuntsevo, a suburb a short distance from Red Square. As always there was plenty to eat and drink and the dinner didn't break up until the early morning hours. Somewhat unusually the chief guard, a young soldier named Ivan Khrustalev, told the others they wouldn't be needed, and the "Boss" said they could all go to sleep. Most unusual.

By noon, Joseph had not yet stirred. True, even when he awoke early, he might not get up until 10:00, so the guards weren't too worried. But after 1:00 p. m., Joseph still hadn't called for his tea. But guards were under strict orders never to wake him should he sleep late.

Finally at 6:30 in the evening the guards saw a light in Joseph's apartment. At least the "Boss" - as they called him - was up. So they expected to be called soon. However, they kept waiting and heard nothing. Finally at 10:00 p. m., Ivan decided to look in. He found Joseph lying on the floor next to a copy of Pravada and in a puddle of urine. His broken watch had stopped at 6:30. Evidently Joseph had gotten up, walked to the table to turn on the lamp, and was felled by a stroke.

You would think the guards would immediately call a doctor. But the best doctors had been rounded up and were in prison at Joseph's orders. So the guards called Beria who told them not to call anyone else. A couple of hours later he showed up and took charge.

Finally thirteen hours after the Ivan found Joseph lying on the floor, a doctor arrived. He confirmed there had been a stroke but thought a second opinion was merited. So he was driven to the prisons to consult with the top specialists. They agreed with the diagnosis and said there wasn't much anyone could do other than wait and hope for the best. Which in their case wasn't the best, at least not for Joseph.

Other members of Joseph's circle arrived to wait the inevitable along with Lavrenty: Nikita, Georgy, Vyacheslav, and Nikolai. One story was that when it became clear Joe would probably not recover, Beria began striding around the room bad mouthing Joseph in most discourteous terms. Then Joseph began to stir, and Lavrenty threw himself on his knees by the sofa and began kissing Joseph's hand. Only then, we read, did Stalin die.

The date was March 5, at 10:00 p. m. Ironically, on that day Sergei Prokofiev also died, fortunately not in a labor camp but in his Moscow apartment. But he missed surviving the Horrible Stalin Years by one hour.

Sergei Prokofiev

He didn't survive.

References

There are biographies on Josef and much about the Russian Revolution.

Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar, Simon Sebag Montefiore, Knopf, 2004. This book mostly covers Joseph in the years he was in power but also has information on his childhood and his rise to be Lenin's right hand man.

Everyday Stalinism: Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times - Soviet Russia in the 1930's, Sheila Fitzpatrick, Oxford University Press (2000). A book that explains why Stalin lasted as long as he did, oddly enough by creating a stratified society where there was various levels of special privileges. Even today there are people who lived through the times of Stalin that - amazing as it seems to us - yearn for the good old days.

The Unquiet Ghost: Russians Remember Stalin, Adam Hochschild, Viking, New York, 1994. A book based on interviews of people who experienced first hand Stalin's labor camps and prisons.

The Last Days of the Romanovs: Tragedy at Ekaterinburg, Helen Rappaport, St. Martin's Griffin, 2010

"Soviet Labor Camp: A Trove of Photos", Elizabeth Neuffer, The New York Times, June 29, 1987. The labor camps did not end with the death of Stalin and indeed continued at least until the fall of the Soviet Union in 1989. This article is about Georgi Mikhailov, a physicist who taught at the University of Leningrad and whose - quote - "crime" - unquote - was collecting and exhibiting works of underground artists. Professor Mikhailov spent three years in the 1980's in a labor camp. The conditions were definitely less severe than in the days of Stalin, and he was, Mr. Mikhailov says, the only political prisoner out of 600 inmates. The others were indeed criminals, criminal being fairly loosely define, and some were alcoholics sent there to recover. But the system of imprisoning people who happened to like modern art changed dramatically under the time of Mikhail Gorbachov, a time, as we also know, that brought the Soviet Union a-tumbling down.

"Soviet Ends Silence on Stalin Wife's Suicide, New York Times, April 14, 1988

"Disordered personalities at work", Belinda Jane Board and Katarina Fritzon, Psychology, Crime and Law. Not surprising to anyone who's had a boss.

"The 1932 Harvest and the Famine of 1933", Mark B. Tauger, Slavic Review, Volume 50, Numbe1, Spring 1991, pp. 70-89. A rather technical paper, but very useful as it shows how careful review of data can help sort out what really happened in the Days Stalin Ruled. The paper shows how the larger conspiracy theories that Uncle Joe artificially created the Ukraine famine are certainly not correct, but that his system of collectivization and forced allocation of grain did.

Although listing the following books opens CooperToons to spittle flinging diatribes, it is necessary to point out that other countries - even "enlightened" ones - are by no means immune from horrible actions. A usual response is that these events happened "long" ago, compared to Uncle Joe's times, which is certainly not true in the time scale of history. What Joseph and dictators of his ilk did - like Hitler and Pol Pot - was to compress the number of his victims into a fairly short period. The horrible happenings of the - quote - enlightened countries - unquote - tend to be spread out more and were not often due to the machinations of a number of individuals who were working toward some alternative higher sounding goal, such as the courteously called Manifest Destiny, which allows deaths and genocide to be dismissed as unfortunate consequences.

American Holocaust: The Conquest of the New World, David E. Stannard, Oxford University Press, 1992. The estimate is that 10,000,000 million Native Americans died due to "policies" of the US government. The numbers seem high and are largely dismissed by those who prefer the idea that the population of the not-yet-United States was very low before European settlers arrived. However, so-called villages, even in North America, could have thousands of inhabitants and sometimes were larger than many - quote - "real cities" - unquote - that were later established by the Europeans. Some also say the policy was not deliberate extermination, but the word was used by men like William Tecumseh Sherman, on how how to handle the Indians who didn't want to settle on the reservations.

Worse Than Slavery: Parchman Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow Justice, David M. Oshinsky. Free Press, 1996. A history of the early post-bellum picture of the southern penitentiary system, particularly the state prisons in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. This book is seen largely through the convicts eyes, and one thing that has to be remembered is the wide variation in how the prisons were run, particularly regarding the race of the inmates. Therefore it is possible to pick and choose data that shows the American prison systems were humane and focused on rehabilitation - such as the prison in Missouri where Blanche Barrow was incarcerated - or showing the prisons were as a bad as anything Joseph wrought - such as in the book listed below.

Scottsboro Boy Haywood Patterson and Earl Conrad, Doubleday, 1950. Some may dismiss this as leftist propaganda and it certainly was written as an indictment of the southern justice system of the 1930's. Still, the pictures of prison life in the 1930's south is accurately pictured and confirmed by other, more scholarly research. It's also true that many southern (and yes northern) prisons were horrible places for people of all races and it was the fear of returning to jail that made people like Clyde Barrow swear they would never be taken alive.