Leonardo da Vinci

andAndrea del Verrocchio

(In Which the Life and Works of the Great Italian Master Artist Leonardo Da Vinci are Discussed Including Details of His Art, Research, Finances, Friends, Family, Name, Diet, and Personal Preferences, Information Which is Supplemented with Images of Paintings, Drawings, Sculpture, and Currency to Enhance the Learning about the Great Maestri of the Italian Renaissance with Supplementary Illustrations from Guest Artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Andrea del Verrocchio, Michelangelo Buonarroti, Giorgio Vasari, and Bastiano da Sangallo)

(Psst! The picture is really Philippe and Mario.)

(Click on the image to zoom in and out.)

| "In truth in the art of sculpture and painting he had a manner somewhat harsh and crude, like those who gained more with infinite study than with the benefit or ease of natural ability." | |

| ‐ | Giorgio Vasari, The Lives of the Most Excellent Italian Architects, Painters, and Sculptors from Cimbaue Up to Our Own Times (Le vite de piu eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori italiani, da Cimabue insino a' tempi nostri), 1550. |

No, no. The quote is not about the great artist and maestro Leonardo da Vinci. Instead it was written about the great artist and maestro Andrea del Verrocchio who just happened to be Leonardo's teacher.

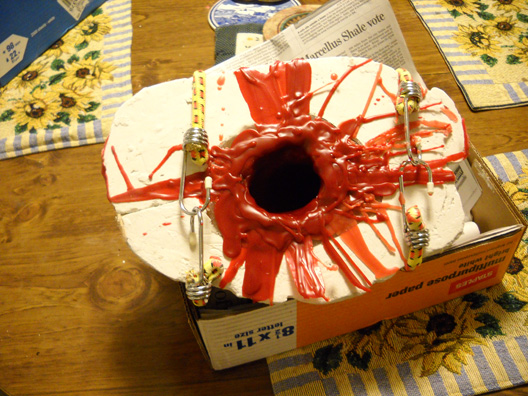

Of course, this isn't a rendering of the real Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci and Andrea di Michele di Francesco de' Cioni detto del Verrocchio. Instead we are looking at, well, "portraits", of the French actor Philippe Leroy (who played Leonardo) and Italian performer, art director, and production designer Mario Molli (who played Andrea). This is as they appeared in the 1971 television mini-series La Vita di Leonardo Da Vinci which was released in English as The Life of Leonardo da Vinci.

Actually we're representing a scene in the mini-series a bit anachronistically and switching the casting a bit. The TV show depicts Leonardo from the time he was an infant until he was an old man, so naturally they had to use different actors. In the scene shown here Leonardo is still a student in Andrea's workshop and Leonardo's part was filled by actor Arduino Paolini. It was in the next scene that Philippe took over as Leonardo, the role he assumed through the rest of the series.

The picture on the easel is The Baptism of Christ. Now in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, this is one of the few paintings that can reliably be attributed to Verrocchio. However, the angel on the left has been universally accepted as being painted by Leonardo. Such collaborative work is typical of art produced from the Renaissance to the 18th Century, and even today the most successful artists don't do everything themselves but have assistants and students.

That Leonardo worked on the painting has been deduced from both the style of certain parts, the paints used, and documentation of a sort. Leonardo's first biographer, the Italian Renaissance artist Giorgio Vasari (1511 - 1574), specifically states that Leonardo painted the angel on the left. He also adds that when Andrea saw the painting and realized the pupil had outstripped his master, he vowed never to touch paint and brushes again. Giorgio, we must point out, did not personally know Leonardo but he did interview people who did. One of Giorgio's sources was Francesco Melzi, who was one of Leonardo's pupils and assistants in his later years.

Art historians have generally concurred with Giorgio's attribution and point out that the angel on the left has smoother contours and was rendered in chiaroscuro (pronounced kie-roh-SCUR-oh) and sfumato (sfoo-MAH-toh) . That is, the painting has strongly contrasting light and dark areas which are gradually and smoothly blended. The hair also exhibits very Leonardoesque curls, and portions of the background are in the style Leonardo used in his later paintings. The smooth contours and shading were possible because Leonardo was using those new-fangled oil paints rather than egg tempera which was what the early Italian Renaissance artists worked with.

Egg tempera, for those not of the cognoscenti, are paints made by grinding the dry pigment powders with the yolk of an egg. The paint dries quickly and does not lend itself to blending in the same manner as oil paints which dry much more slowly. Tempera can dry in minutes, while oils can take hours just to "set" and might take a full day to feel dry to the touch. But for oil paints to completely dry it can take - literally - weeks or longer.

Because tempera dries quickly and produces nice bright colors it might be compared to modern acrylic paintings. However, egg tempera is more fragile and remains water soluble even after drying. You can take a damp cloth and wipe out a dried tempera painting. Acrylic, which although today is usually a water based medium, dries to a water-insoluble surface. However, some organic solvents can remove dried acrylics.

The general consensus, then, has been that Andrea painted three of the figures in tempera and Leonardo painted the angel on the left in oils. In virtually all books about Leonardo this is what you read.

But just when you think everything is figured out someone comes along and goobers it all up! A re-examination of the painting - using X-ray and infrared analysis - indicates that the original paints of all the figures were laid on in the same manner and that the vast majority of the painting - including the angel on the left - was rendered in tempera. So one art historian has decided that yes, Leonardo did work on the painting but it was substantially complete before he stepped in. The conclusion was that Leonardo's contribution is best described as "touching up" the painting in oils rather than creating parts of it independently as Giorgio implies.

In addition to his importance as an author and artist, Giorgio has other distinctions of note. For one thing, he painted over one of Leonardo's two murals. This was the Battle of Anghiari (pronounced ahn-YAH-ree) which had been commissioned by the city of Florence to decorate a wall in the Palazzo Vecchio (pah-LAHTZ-oh VECK-ee-oh), the "Old Palace" which served as the town hall. But rather than paint in fresco - watercolor on wet plaster - Leonardo decided to paint in oil and expedite the drying by applying heat.

Images of the guest artists can be clicked to open in larger formats in new windows.

Battle of Anghiari

Leonardo da Vinci

(Copy by Peter Paul Rubens)

(Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons, Louvre)

Of course back then the only way you could heat anything was by fire. No details were given other than stating Leonardo made a charcoal fire in front of the painting - certainly not advisable in a closed space. According to Giorgio, the lower parts of the painting did dry OK. But in the areas higher up it seems that the heat just dropped the viscosity of the paint and it began to drip and run down the wall. Che casino!

As an interesting parenthetical note, at the same time another local artist was commissioned to paint a mural on another wall in the Palazzo Vecchio. That was a 25 year old Michelangelo Buonarroti who had been hired to commemorate the Battle of Cascina (pronounced CAH-shee-nah), which took place on July 28, 1364, when the Florentines fought the Pisans.

Battle of Cascina

(Copy by Bastiano da Sangallo After Michelangelo)

(Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons, Holkham Hall, Holkham, England)

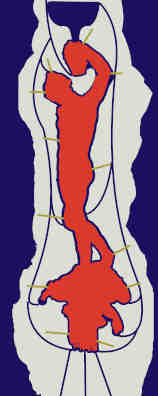

Actually Michelangelo's painting was going to show a non-battle where some of the Florentine army were taking a dip in the Arno River when someone gave a false alarum that the Pisans were coming. Naturally there was pandemonium as the Florentine soldiers clad in nothing but their birthday suits were scrambling to put on their accoutrements and gather their armaments.

Although it is true that Michelangelo preferred sculpture, like all capable Renaissance artists, he would provide whatever kind of art his clients wanted. His skills as a draftsman were actually superior to Leonardo's and he had studied fresco painting in the workshop of Domenico Ghirlandaio who was the greatest fresco artist of the time. So Michelangelo actually had formal training as a painter and but it wasn't with Domenico that he really learned sculpture.

Giorgio Lives of the Artists tells us that when Michelangelo, later a friend of Giorgio, was living with Lorenzo de Medici, he was taken in hand by Bertoldo di Giovanni. Bertoldo was the sculptor in residence in Casa Medici and had studied with Donotello, arguably the greatest Renaissance sculptor. So although we can be sure that Michelangelo taught himself a lot, he didn't teach himself everything.

From the verb tenses used above, the discerning reader may guess that the Battle of Cascina was never completed. In fact, Michelangelo did less than Leonardo and finished only the preliminary drawing - the cartone (pronounced car-TOHN-ay), a word that is rendered as "cartoon" in English - before he was summoned to Rome by Pope Julius II to paint the Sistine Chapel. The only picture we have of the Battle of Cascina is a copy that Michelangelo's contemporary, Bastiano da Sangallo, made of the cartoon.

Michelangelo and Leonardo, by the way, did not like each other a-tall. There's one story from an anonymous manuscript about a rather fractious meeting between the two artists on the streets of Florence. A group of men had been sitting outside a tavern reading Dante's Inferno and were arguing about one of the passages when they saw Leonardo. They asked Leonardo his opinion on the interpretation but he, too, was stumped.

But then Leonardo saw Michelangelo come walking by. Michelangelo was known as something as a whiz on Dante - supposedly he had memorized the whole book - and so Leonardo said they should ask Michelangelo. Mistaking what was intended to be a compliment for sarcasm, Michelangelo sneered that Leonardo would do better to explain why he couldn't finish his projects. Given that Michelangelo didn't finish the Battle of Cascina this seems to be a case of the pot calling the kettle round.

Leonardo got his payback, but in a roundabout way. In his notebooks he comments about how not to draw well-defined muscular men which is almost certainly a shot at Michelangelo's technique. Leonardo commented that in some figure drawings:

"... you would think you were looking at a sack of walnuts rather than the human form, or a bundle of radishes rather than the muscles of figures.

"Sack of Walnuts" - Michelangelo

(Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons)

Then he makes a real snipe at Michelangelo's preferred art:

"The sculptor in creating his work does so by the strength of his arm by which he consumes the marble. This is done by a most mechanical exercise, often accompanied by great sweat which mixes with the marble dust and forms a kind of mud daubed over his face. The marble dust flours him all over so that he looks like a baker. His back is covered with a snowstorm of chips, and his house is made filthy by the flakes and dust of stone.

But the painter sits before his work, perfectly at his ease and magnificently clothed, and moves a very light brush dipped in delicate color, and he adorns himself with whatever clothes he pleases. His house is clean and filled with charming pictures, and often he is accompanied by music or by the reading of various and beautiful works which, since they are not mixed with the sound of the hammer or other noises, are heard with the greatest pleasure."

Michelangelo Buonarroti

A Most Mechanical Exercise

For years, Leonardo's ruined painting of the Battle of Anghiari was visible on the wall in the Palazzo Vecchio. We sort of know what it looked like since it was copied by other painters. Then in 1565 Giorgio himself was commissioned to paint a mural commemorating the Battle of Marciano (no relation to Rocky) on the wall where the remnants of Leonardo's painting were still visible. The Battle of Marciano was fought on August 2, 1554 when the Florentines defeated the army of the Republic of Siena.

Whether Giorgio actually destroyed Leonardo's painting or just covered it up with a new surface is unknown. Certainly everyone would like to find a "lost Leonardo", but tearing down an authentic painting by Vasari in near perfect condition to uncover a ruined painting by Leonardo that may no longer exist is something no one has been willing to do.

After Leonardo abandoned the painting he took off to Milan much to the chagrin of Florence's city officials, particularly Piero Soderini, the town's gonfaloniere (i. e., head honcho). The city was paying Leonardo 3000 florins for the painting and had given him a sizeable advance plus 15 florins a month while he worked. So Leonardo leaving them with a ruined painting and hieing off to a principality that was ruled by the French invoked much choler. On the other hand we have to wonder just how much 15 florins a month really was.

According to one academic report, a gold florin in Leonardo's time was equivalent to 33 US dollars. By this estimate Leonardo was making not quite $500 a month in today's moolah. On the other hand, this exchange rate seems to underestimate the coin's purchasing power since Leonardo had to support not only himself but the expense of his workshop and his assistants' salaries as well.

Leonardo's notebooks have a lot of references to money. He often refers to the cash in soldi, but he also mentions florins, lire, scudi, and denarii. To modern readers the monetary exchanges and values are confusing at least in part because the sources aren't entirely consistent.

The value of a coin was officially determined by the weight of the metals and official exchange rates but complicated by fluctuating market values between gold, silver, copper, and bronze. Bankers and money changers had scales to weigh the coins to assure they had not been shaved down and they assessed the purity of the metal by a number of ways.

The fundamental monetary unit in Florence was the florin. It was a surprisingly stable currency and the coin did not vary in weight or composition in the years it was in circulation. That was from 1252 to 1533. Because of its stability and uniformity, the florin became the international unit of commerce.

The florin was composed of pure (24 carat) gold or at least as pure as was possible for the time. One popular informational website gives the weight of a florin to eight significant figures, but the truth is there was variability in the manufacturing process. It did, though, have pretty tight specifications. The coin was typically 21-22 millimeters in diameter (about 0.85 inches) and weighed between 3.46 to 3.53 grams (about 0.12 ounces). At today's market price this would make a florin worth about $210.

The soldo was the fundamental division of the florin. How much a soldo was worth is complicated by the coin being silver, and then as now the exchange rate between the two metals changed over time. Fortunately, Leonardo's detailed notes help us out where he sometimes mentions the same amount of money in different units, and it's clear that in Leonardo's Italy there were 20 soldi to 1 florin.

But returning to the question of the value of 15 florins, Leonardo mentions that 27 soldi would buy three pounds of wax. That was almost certainly beeswax and one modern vendor sells 3 pounds for $8. So if we use this "beeswax exchange rate" we have slightly less than 30 cents per soldo. Taking 1 florin as 20 soldi, Leonardo's salary of 15 florins a month was not the $500 of the academic estimate but only about $90. We're talking about a difference of a factor more than five, for crying out loud!

Every now and then Leonardo mentions using ducats. This was a gold coin originally from Venice and its weight was almost equal to the florin. So in modern rates the value of the two coins can be considered essentially the same.

Similarly Leonardo would refer to the lira (pl. lire). The lira was a silver coin and from Leonardo's comments we know the exchange rate was 1 lira = 20 soldi. So once again we have a coin that was equivalent to the florin. The lowest valued coin Leonardo talks about, the denier, was also silver. There were 12 denarii in 1 soldo. A French franc, Leonardo tells us, was worth 48 soldi.

A bit more confusing (and longer lasting) coin was the scudo which depending on when it was minted could be gold or silver. In the 1500's it was gold, the scudo d'oro, and weighed 3.2 - 3.4 grams and so was worth slightly less than the florin. Later silver scudi were much larger, weighing 20 to 30 grams since then as now silver was cheaper than gold.

OK. Just what could Leonardo buy with his florins, lire, soldi, scudi, or denarii (and later his francs)?

Clearly despite the academicians best efforts, giving modern equivalents to early currency is tricky. Usually it's more helpful to find out how much the various workers earned, particularly the craftsmen who would be hired for a flat fee. Then we can compare their wages to those of their modern counterparts to get an idea of how much the old money was worth.

Leonardo was not just a painter, but like other Renaissance artists he was also an architect and engineer. At one point he worked on the logistics of digging a canal from Florence to Pisa and he determined you would have to pay each workman 4 soldi a day. This fits pretty well with the criteria that 1 soldi in Italy equaled about 1 pence in England where workmen had daily wages of 3 - 4 pence. These early English pence were not like modern American pennies which were made of pure copper before the US Mint switched to copper coated zinc. Instead the early English pence were silver - the "silver pennies" for Lord of the Rings fans. Three to four pence was also what you'd pay a priest to offer up prayers on someone's behalf.

Some viewers of sufficient vintage may note that the relationship of the currency:

| 1 Florin | = | 20 Soldi |

| 1 Soldi | = | 12 Denerii |

... has exactly the same relationship as the pre-decimalization:

| 1 Pound | = | 20 Shillings |

| 1 Shilling | = | 12 Pence |

In this case they may think that 1 denier was approximately 1 pence, then we should be able to equate florins and soldi to the English pounds (£) and shillings.

But we've seen this doesn't work since the pound was worth considerably more than a florin. Or at least it was until around the year 1500 when a gentlemen (used as a title of courtesy only) named Henry VIII came along and to get more revenue for his never ending wars, he cut back both the weight of the pound and the percentage silver. But even with this revaluation, one English pence was still counted as one Italian soldo. A silver penny in Henry's time weighed about 0.77 grams and at today's silver price that's worth about 60¢.

English Penny, Tudor Period, Henry VIII

(Reproduced via The Portable Antiquities Scheme, Wikimedia Commons, UK Government)

With his assistants and students living with him, a lot of the cash had to go for comestibles. There is general consensus that Leonardo ate little or no meat and was very conscious of animal welfare. This opinion is not just modern "revisionist" history of bleeding heart liberals. Instead we know this was what his contemporaries said. The explorer Andrea Corsali once wrote to Lorenzo de Medici about his travels and stated the "Guzzarati [the Gujarati in India] are so gentle that they do not feed on anything which has blood, nor will they allow anyone to hurt any living thing - like our Leonardo da Vinci". Giorgio also tells us that Leonardo would go to the marketplace, pay for birds that were in cages, and let them go free.

On the other hand as an artist living in the Renaissance without synthetic materials and plastics, Leonardo could not avoid using animal products. Sizing and glues were made from animal skins, horns, hooves, and bones and we have notes of Leonardo using animal skins to make clothes. Tallow candles were a common source of light, and the number of eggs used to make his tempera paints must have been considerable. The surface for the paper for silverpoint drawings was prepared with powdered animal bones.

Leonardo did not impose his own diet on his assistants and we read that he would pay 1 soldo for a pound of veal. One soldo would also buy a jug of wine, a pound of salt, or a pound of butter, as well as a "quantity" of eggs - probably enough to fill a small basket. And we see in England that such items were similarly valued in pence. Two dozen eggs sold for 1 pence and a gallon of ale would be between 1 - 2 pence. Wine seemed to be more expensive amongst the Albions with a gallon of "good" wine costing 8 pence.

Of course Leonardo had to pay for art supplies. A stylus ran about 20 soldi or 1 florin. Although this seems awful high for a pencil, these "pencils" had points that were made of silver and were used for making metal point drawings. Linseed oil for his paints was 5 soldi per pound. Today the cost runs about $6 per pound. That would make a soldo worth $1.20 and a florin $24 - not all that far from the $33 of the academic estimate.

The cost of pigments varied considerably (as they do now). Yellow ochre was pretty cheap at 1 soldo per pound (today you might buy a pound for $15). Other colors cost more. Cinnabar - mercuric sulfide (HgS), a red (and toxic) pigment - was a whopping 18 soldi for a pound. Green and yellow powders - Leonardo didn't specify what they were - were 12 soldi per pound, and white (probably lead white, basic lead carbonate, Pb2C2H2O5) sold for 15 soldi. Black pigment, probably just charcoal, was 2 soldi per pound.

As far as clothes, Leonardo would pay about 14 soldi for a pair of shoes, 2 lire for a cloak, and 1 lire for a hat. A haircut was 11 soldi and paying for a fortuneteller was 6 soldi - about 50% more than a workman made in a day. And all this was for one of his assistants! Leonardo himself was something of a dandy and a fancy dresser and spent more on his own clothes than for the duds of his assistants. He once spent 2 lire - 40 soldi - just for the material to make a pair of boots.

Although Leonardo's assistants did get a salary, they were expected to pay for food and lodging (perhaps deducted from their pay). One of his helpers paid five lire a month and his dad had advanced Leonardo 2 "Rhenish" florins. But Leonardo would also give them money and often at their request.

Leonardo kept close tabs on how much he doled out. He gave 1 ducat - essentially 1 florin - to one of his most trusted assistants and master of all trades Tommaso di Giovanni Masini (known as Zoroastro). There are also a number of references to Leonardo giving money to another long time member of his entourage, Gian Giacomo Caprotti, who is referred to in his notes as Salaì. The name is pronounced sal-ah-EE in Italian although most English speakers say sal-EYE. It means the "Little Devil".

Leonardo mentions Salaì more than any other assistant and a lot of it is about how much money he gave him. Sometimes it was a loan such as the time he advanced Salaì 17 scudi - about 15 florins - for his sister's dowry. This was, we emphasize a loan. Nevertheless, the amount of money Leonardo handed over to Salaì was often quite large and once he gave him 93 lire and 6 soldi - remember Leonardo got paid only 15 lire (florins) a month for working on a mural. On the other hand, there's one time that it was Leonardo who borrowed 2 ducats from Salaì!

Salaì moved into Leonardo's household at age 10 - young even for a beginning apprentice. This was around 1490 when Leonardo was living in Milan and there was apparently some deal worked out with Salaì's dad who may have wanted the kid out of the house. Salaì was in fact what we would call a "handful" and maybe his dad thought having Salaì apprenticed to a workshop would "straighten him out" to use a term favored by the follicularly sparse in Quaint American Locales. As Leonardo wrote:

Giacomo [Salaì] came to live with me on St. Mary Magdalen's Day [July 22] 1490, aged 10 years. The second day I had two shirts cut out for him, a pair of hose, and a jerkin, and when I put aside some money to pay for these things he stole 4 lire out of the purse, and I could never make him confess, though I was quite certain of the fact.

The day after, I went to eat supper with Giacomo Andrea [Salaì], and Giacomo ate enough for two and did mischief for four. He broke 3 bottles of condiments and spilled the wine.

On the 7th day of September he stole a silver point pen of the value of 22 soldi from Marco [Leonardo's assistant and pupil Marco d'Oggionno]

Thief, liar, obstinate, glutton.

This itemization of Salaì's misdeeds were likely for inclusion in a report to his dad. Leonardo mentioned other instances where Salaì would pilfer money and items. The money he spent; the items he sold for cash.

However, maybe Leonardo did "straighten him out". In later years, Leonardo entrusted Salaì with important responsibilities, and he remained in Leonardo's employ even after Leonardo left for France in 1515. Some scholars don't believe Salaì went along but if he did he was back in Milan around 1518.

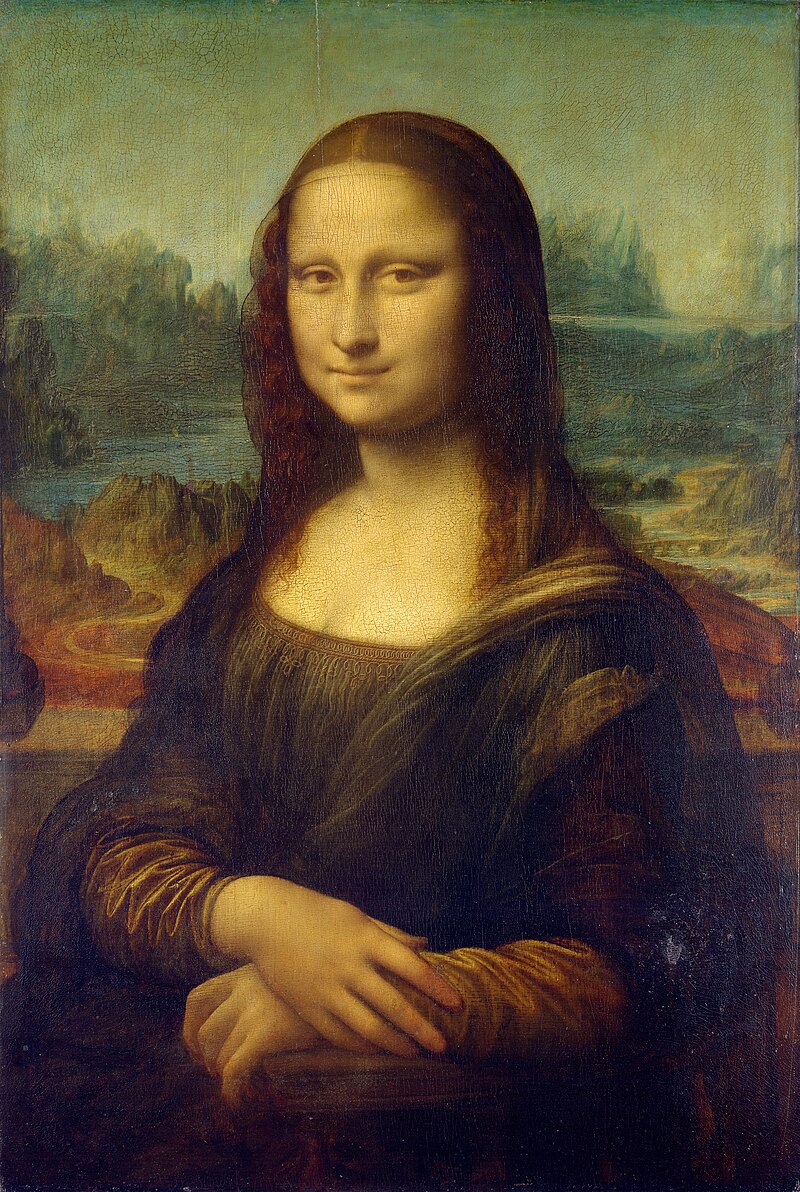

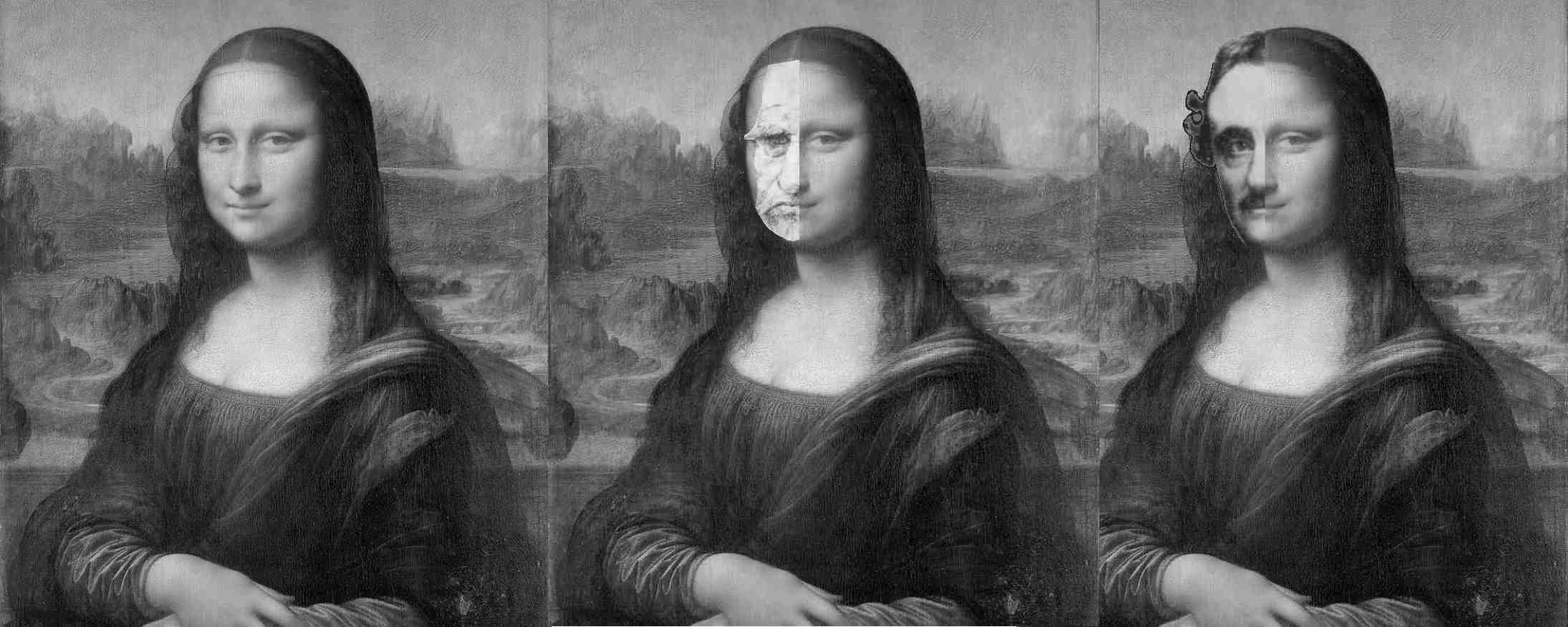

There are paintings attributed to Salaì but critics - perhaps snobbishly - don't consider them top quality compared to those of Leonardo's other students although to the layman they look pretty good. Leonardo's will left the Mona Lisa to Salaì who quickly sold it to the Francis I, the French king with the impressive proboscis. That's why the painting eventually ended up hanging in the King's bathroom before winding its way to the Louvre where it is now.

On June 14, 1523, Salaì married a lady named Bianca Caldiroli. So we see that in his 40's Salaì was independent and presumably a successful artist. But six months later, on January 15, 1524, his career ended. The story often given is he died during a crossbow duel, but the reference says he died ex sclopeto. This could mean he was killed by an actual firearm - a gun - which at the time were becoming in use. So Salaì may have been one of the first victims of gun violence.

Although identification of Salaì as a model for Leonardo's paintings (such as the painting of St. John) is necessarily speculative, it was common for apprentices and assistants to pose for paintings or sculptures. Leonardo himself is sometimes identified as the model for Verrocchio's bronze statue of David.

Much has been made of the way Leonardo's art depicted young men and today it is generally accepted that Leonardo preferred same gender relationships although even past the mid-20th Century this topic was often skimmed over. In the mini-series there is a scene where Leonardo (played by Philippe) and some of his buddies are hauled before the magistrates. The narrator, Giulio Bosetti, postulates that Leonardo had been accused of heresy since according to one contemporary writing, Leonardo's beliefs "were more philosophical than Christian".

Actually it is true that in 1476 Leonardo was arrested but it wasn't for heresy. Instead it was on suspicion of comporting himself with one Jacopo Saltarelli. Evidently someone had seen a bunch of young men congregating in a manner suggesting to the suspicious minds that there was whoopee going on.

So someone left a written "denunciation" in a drop-box that was set up for that purpose. The note named Leonardo and several others who were hauled to the police station (and may have even been jailed). But when they appeared before the judges, one of the defendants turned out to be a member of the Tornabuoni family who was related to the Medicis. The Medicis were more or less the de facto if not always de jure rulers of Florence.

In the late 1400's, the head of the Medicis - and hence of Florence - was Lorenzo di Piero de' Medici, also known as Lorenzo il Magnifico (the Magnificent) or just "Il Magnifico" to his friends. The case against Leonardo and his buddies was dismissed, perhaps less for Lorenzo's familial associations than the fact the accuser didn't show up and there really wasn't any evidence against them anyway.

Historians have suggested that the informant was possibly a competitor of Leonardo's boss, Andrea del Verrocchio, and was acting with sour grapes against the more successful artisan. Also from a comment in Leonardo's own notebooks, it may be that Jacopo, who was apparently an apprentice to a goldsmith, had done nothing more than serve as a model for some drawings. So the accusation could have just been a case of guilt by association.

On the other hand, it's quite possible the charges were true. Renaissance Italy had a culture where social mixing of the genders was strictly controlled. Ladies were kept indoors until they were married off usually to men in their thirties. So young men in their formative years were bereft of proper feminine companionship and were thrown together and left to their own - ah - "devices".

Although the actual charges made to the Officer of the Night - the head of the vice squad - were fairly common, out of the 100 - 200 accusations per year maybe only 5 would end in convictions. And even then, although nominally involving a capital crime, most convictions resulted in a fine or in more extreme cases exile.

By the time of his trial Leonardo was 24 years old. He had been born in 1452 in the village of Vinci which is about 15 miles west of Florence. Hence the name "Leonardo da Vinci", that is "Leonardo from Vinci" (some authors think he was born in Anchiano but "Leonardo d'Anchiano" just doesn't cut it).

Now some art historians get quite huffy when people call Leonardo just "Da Vinci" which they point out is not a name at all. You can call him Leonardo or Leonardo da Vinci, they say, but never just "Da Vinci".

Actually it was not unusual to address certain people by the town that their family came from. That was particularly true for the nobility. For instance, Charles d'Ambroise (pronounced sharl dam-BWAHZ) whom we'll hear more about later, was a French nobleman who became a friend and supporter of Leonardo. But when his friends addressed him they would not call him Charles - first names weren't really used except by close family members - they would just say "d'Amboise". So if we can call Count Charles d'Amboise by the town he was from, we certainly can call the Prince of the Arts Leonardo da Vinci as "Da Vinci".

Leonardo's dad, Piero, was a notary, a job that in the Renaissance involved drawing up contracts and documents for businesses and individuals. Being a notary was a pretty high class career and Piero had the honorific title "Ser". But there was one wee little glitch in Casa Da Vinci.

You see, Leonardo's mom, Caterina, and his dad, Ser Piero, weren't married. Caterina was possibly a farm girl - "peasant" is the word usually used - or a domestic servant. Recently there's been the theory she was actually a slave from the Middle East, although tax records show her father was a local man who died young and afterwards Caterina lived with her grandmother.

Whatever her actual situation, Caterina was not deemed a suitable spouse for an up and coming professional man. Certainly she would have had a minimalist dowry - which is the money paid to the husband from the bride's family - and no self-respecting Florentine swain would ever marry a woman whose family couldn't provide respectable funding.

Nevertheless Ser Piero acknowledged Leonardo as his son and took him into his home. Normally Leonardo would have followed his dad's career, and a number of explanations have been advanced as to why he didn't. In the mini-series Leonardo's grandfather, Antonio, is ragging on Ser Piero about getting Leonardo to learn a trade. Antonio says because Leonardo's a - well, we won't use the word - but because Leonardo was born on the other side of the sheets so to speak, he would never be allowed to be a notary. The other explanation is that other notaries would not accept a - well, there's that word again - into their guild. On the other hand, there were other guilds that had no problem with someone with Leonardo's background joining up.

So perhaps we should just accept the simplest explanation and one suggested by Vasari. It's that Ser Piero noted his son had exceptional artistic talent and arranged for Leonardo to be apprenticed to Verrocchio whom he knew personally.

The skills of the Renaissance artists were a bit more fundamental to daily life than they are today. Far from working alone in a garret and randomly splattering paint on a canvas and calling it Man's Inhumanity to Man, an artist worked less in a studio in the modern sense than in a workshop - bottega is the Italian word. A bottega could, like that of Verrocchio, be of considerable size. These botteghe produced products that ranged from silverware to buildings. And because there were no digital cameras, if you wanted a picture of friends and family, one of the most popular items were portraits, whether paintings or statues, sold on commission.

It may surprise modern artists how exacting - quibbling, in fact - the contracts were drawn up specifying exactly what the artist was to paint. None of this "artistic expression" jazz where the buyers are surprised when they see the unveiled artwork. The clients not only specified what they wanted almost to the brushstroke, but they could monitor the work in progress. In a contract drawn up by a Benedictine monastery for a painting by Pietro Perugino, one of Leonardo's friends and fellow students, the monks stated exactly what they wanted:

The picture must be painted in the following way: In the rectangular panel, the Ascension of our Lord, Jesus Christ, with the figure of the glorious Virgin Mary, the Twelve Apostles, and some angels and other ornaments, as may seem suitable to the painter. In the semicircle above, supported by two angels, should be painted the figure of God the Almighty Father. The predella [the raised step at the base of an altar] below is to be painted and adorned with stories according to the desire of the present Abbot. The columns, however, and the mouldings and all other ornamentation of the panel should be embellished with fine gold and other fine colors, as will be most fitting, so that the panel will be beautifully and diligently painted, embellished and gilded from top to bottom as stated above and as it befits a good, experienced, honorable, and accomplished master. Paints, gold, and other things necessary and suitable for the execution of the said painting, as well as for the ornaments of the said panel, 500 gold ducats, payable within four years at the rate of one quarter of the sum each year. In said account, however, the frame which surrounds the panel is not to be included, nor the ornaments placed at the top of said frame, but only the panel itself with its ornaments.

And Leonardo? Well, in 1481 - he was almost thirty - he had a contract drawn up by his dad for a painting commissioned by the Augustinian monastery of San Donato at Scopeto about 40 miles southeast of Florence. The contract is, well, weird, and the only explanation for terms so unfavorable for the artist is that Leonardo had gotten a reputation for being unreliable and a procrastinator and for not delivering his art on time if at all. This was a reputation, by the way, that followed Leonardo all his life.

The payment was not in cash, but was one-third of a section of land which he could sell back to the monastery for 300 florins but only if the monks wanted it back. But he couldn't sell it for three years. Since the painting was to be completed in at most thirty months, Leonardo wouldn't get any money until the painting was completed. This was not the standard way of paying for artwork. Usually the artist was paid as he went along with the final payment made upon the completion of the work. And Leonardo also had to pay for the paints and other supplies himself.

But the part of the contract that was really weird was that Leonardo had to pay 150 florins. Yes, Leonardo had to pay 150 florins. Nominally this was for the dowry of the daughter of someone named Salvestro di Giovanni who must have been a benefactor of the monastery. But is seems that the monks wanted some kind of surety before they would give Leonardo the job.

The net terms of the contract - 150 florins - was not a bad fee for a painting if it had been upfront and in cash. But the roundabout way of getting the dough gave Leonardo trouble. Soon he had to go to the monks and ask them for a loan to pay, not only for the paints but for the dowry as well. We don't know if the monks agreed with the new terms, but they did give him some firewood and a barrel of wine provided he would also decorate one of the monastery's clocks. They also reminded him that he had incurred an additional debt to them for a barrel of wine they had already advanced.

The monks were wise to hold off on payment for the painting since Leonardo never finished it. The Adoration of the Magi which hangs in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence is simply the preliminary "underdrawing" on a wooden panel. During recent restoration work varnish was found actually seeped into the layer of the paints. This happens when you varnish before the paint fully dries. Since the conservators couldn't remove the varnish without destroying the paint, it was decided to halt conservation and restoration, and the painting returned to the gallery.

It seems a bit odd that Leonardo varnished the painting before it was done. But the varnish was likely a protective measure since much of the painting is in the non-permanent media of charcoal and watercolor as well as in oils. Besides, the contract did specify that if Leonardo didn't finish the painting on time, the monks could turn it over to someone else. So coating the surface would help insure the painting would still be in good shape for whoever would finish it. Ultimately the monks asked Filippino Lippi, a near contemporary of Leonardo, to do the job. But Filippino started his painting from scratch, leaving Leonardo's Adoration incomplete and to eventually wind it's way to the Uffizi.

Now Leonardo was in debt to a group of irritated monks. That plus the unpleasantness of the Saltarelli affair seems to have soured Leonardo on remaining in his hometown. So he borrowed a modus vivendi that became common in the American West. He just decided to up and "git".

But where? Well, he decided to follow Horace Greeley's advice but not in the same direction. The young man went north.

North to Milan, that is.

From the fall of Rome in 476 to past the mid-19th Century, Italy was not a single country but was a group of "nation states" where everyone just happened to speak some dialect of Italian. Milan, the chief city in Lombardy, was ruled by the Sforza family and in 1482 when Leonardo arrived the Duke was nicknamed Ludovico il Moro or Ludovico the Moor because of his swarthy complexion.

Giorgio tells us that Leonardo was actually sent to Milan by Lorenzo de Medici to play the lyre for Ludovico. As with so much about Leonardo the story can be called into question. Before he stopped by the Duke's palace, he wrote a letter introducing himself and offering his services. So it may be that when Leonardo arrived in the city, the Duke didn't even know who he was.

What strikes the modern reader strange is that in his letter Leonardo claimed to be a military engineer who just happened to dabble in art on the side. But one of the most popular pastimes among the Renaissance dukes, princes, counts, and kings was to wage wars against your neighbors, friends, and family. So Leonardo emphasized the skills that he thought would appeal to the Duke.

Leonardo claimed - among other things - that he could make "an infinite number of items for attack and defense." Among these "infinite number of items" - and that's a lot of items - were portable bridges for armies to cross rivers, cannons, catapults, digging under castles, destroying their walls, and removing the water from their moats. Oh, by the way, Leonardo added almost as an afterthought, "in times of peace" he could "carry out sculpture in marble, bronze, or clay" and he could also "do in painting whatever may be done, as well as any other".

We have to admit that Leonardo is blowing a lot of hot air here. Remember we're talking about an artist whose major accomplishment up to that point was leaving an unfinished painting at a monastery, couldn't afford to buy paints, and had to accept payment in firewood for painting a clock. Scarcely the military wunderkind as described in the letter.

Then almost as a coda Leonardo added "I would also be able to work on the bronze horse to be erected for immortal glory and everlasting honor for the memory of your illustrious father and the stately House of Sforza." It was well known that Ludovico had been wanting to have an impressive monument built to commemorate his dad, Francesco Sforza the First. So Leonardo offered his services.

Leonardo's Horse is without doubt the most famous sculpture that doesn't exist. He fashioned the full-sized model in clay in the Corte Vecchia which is now the Royal Palace of Milan. The statue was unveiled in a field where Ludovico threw a party. All that remained was to cast it in bronze.

The Horse, as everyone calls it, was 24 feet high and no one really knows what it looked like. However, there are drawings in his notebooks that are possibly his first ideas, and there is a small model in a private collection that may have been Leonardo's early prototype.

Originally Leonardo probably planned a statue of Ludovico's father astride the steed. Over the years bronze versions of the horse have been cast and put on display in places as varied as Milan, Vinci (Leonardo's birthplace), Grand Rapids (Michigan), Sheridan (Wyoming), and Allentown (Pennsylvania). Most of the reproductions are not full size and all of them are just a horse sans rider.

But when Leonardo first arrived in Milan there was uncertainty of the Duke's patronage, and so Leonardo had to set up as an independent artist. One of his early works was in collaboration with the De Predis brothers, Ambrogio and Evangelista. They had been contracted to provided a triptych - an altar piece in three sections - and Leonardo's contribution was the centerpiece, now known as the Virgin of the Rocks.

The painting was commissioned in 1483 by the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception of the Church of San Francesco Maggiore in Milan. And yes, Leonardo outdid himself with his usual celerity and the painting wasn't completed until 1508, 25 years later.

First of all what is a confraternity? Well, that's a group of ordinary people who form an organization for some religious purpose. These "lay members" are not priests or monks or otherwise have taken holy orders. The actual purpose of a confraternity is pretty much up to the members to decide.

What exactly happened with the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception is a bit murky as is so much about Leonardo. One story is that the Confraternity agreed to pay the first 800 lire in installments and a final payment to be decided later. Then when the painting was finished Ambrogio said there had been cost overruns and they needed over a thousand florins more.

But the Confraternity complained that they didn't think the painting was actually finished. So Ambrogio agreed to work on it some more. Considerably irritated by nigh on a quarter of a century wait and a final price over twice the original quote, the Confraternity members considered themselves generous when they paid an extra two hundred.

That, we must hasten to say, is one story. What is definitely known is there are two renderings of the painting; one version is in the National Gallery in London and the other in the Louvre. For a long time if you were from England you thought the London version was Leonardo's original and if you were from France you vouched for the one in the Louvre. Now, though, it's generally (but not universally) thought that the painting in London was the second version and that was the one the Confraternity actually got. The theory is that Leonardo got so irritated that the Confraternity wouldn't pay the extra cash that he sold it to someone else. Then with the brouhaha of the Confraternity demanding their painting, he quickly banged out a copy and gave it to them.

There was one painting that Leonardo completed in Milan and for him it was expedited delivery as it only took three years. That was The Last Supper and was painted on a wall in the refectory (dining room) of the Church of Santa Maria delle Grazie about a mile west and a bit north of the Corte Vecchia. A young apprentice monk, Matteo Bandello (later a successful novelist), left us a first hand account of Leonardo at work:

Sometimes he stayed there from dawn to sunset, never once laying down his brush, forgetting to eat and drink. At other times he would go for two, three or four days without touching his brush, but spending several hours a day in front of the work, his arms folded, examining and criticizing the figures to himself. I also saw him, driven by some sudden urge, at midday, when the sun was at its height, leaving the Corte Vecchia, where he was working on his marvelous clay horse, to come straight to Santa Maria delle Grazie, without seeking shade, and clamber up on to the scaffolding, pick up a brush, put in one or two strokes, and then go away again.

Although to many this is description of a dedicated artist trying to produce a exceptional work for his clients, that's not the way the monks saw it. Instead, they would walk into the refectory and as like as not see an unfinished and unattended painting while Leonardo was off and about somewhere else. As the work stretched past one and two years and into the third, they pointed out that the painter Giovanni Donato da Montorfano had started a mural on the opposite wall at the same time as Leonardo. And Giovanni's painting had 50 - count 'em - 50 figures and was completed in only a year. When the prior, the head of the monastery, complained to Ludovico about Leonardo's glacial pace, Leonardo simply replied that men of genius are doing the most when they are doing the least.

But the real delay, Leonardo said, was that it was hard to find someone with such evil features to serve as the model of Judas. Of course, Leonardo smiled, he could use the features of the prior. Ludovico took it as a joke, but the prior decided to leave Leonardo alone and go back to gardening. Then Leonardo went ahead and finished the painting in 1498.

The Last Supper

Leonardo da Vinci

(Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons, Santa Maria delle Grazie)

You may read in some places that The Last Supper is painted on plaster with egg tempera and so is a fresco. The first part of the statement is sort of true; the second part isn't.

A proper fresco is painted using watercolors - pigments mixed with water - on wet plaster. The colors therefore sink into the plaster and become part of the wall. Properly done, a fresco will last as long as the wall which can be thousands of years.

The problem with fresco painting is that as the name implies it is painted freshly. That is, you have to lay down wet plaster each day where you want to paint. You also have to paint quickly and corrections are not easy. Correcting a fresco is like repairing the Autobahn. You don't just change a small part. You have to replace the whole surface of the section - the giornata. You then reapply the paint while the plaster is still wet. So a fresco painting requires considerable preparation and planning.

That wasn't Leonardo's style. Yes, he would make detailed plans for a painting but he liked to think while he worked and change his mind. Yes, Leonardo painted The Last Supper on plaster and he did use tempera. But the painting was on dry plaster, not wet. And Leonardo used not just tempera but oil paints as well.

Now it is possible to combine what appear to be two incompatible media - water soluble tempera and water insoluble oil. Egg yolk is a natural emulsifier and so you can produce mixed tempera-oil paints. It's also possible to gradually add thin layers of the paints over each other, alternating between the tempera and oil glazes. But if Leonardo decided to get too experimental, he may have ended up producing paints that didn't blend together.

Another problem with painting murals of any kind is moisture which if absorbed will cause the walls to flex and bend and crack the paint. Worse, if the temperature drops below freezing - not unusual in Milan in January - the ice can crack the walls and the paint can flake off.

Deterioration of The Last Supper was noticeable even during Leonardo's lifetime when one visitor commented that the painting was starting "to spoil". And only 40 years later when Giorgio saw the painting his comments were recorded in an unobtainable edition of his writings. Depending on how you translate the Italian, he referred to the painting as a "muddle of dots [or blots]" or "a confused blur".

The problems with painting both The Last Supper and the Battle of Anghiari illustrates a point about Leonardo that people don't mention much. Despite his undoubted genius and talent, Leonardo could easily overestimate his level of technical expertise and so make a hash of things.

Another project where Leonardo probably would have made a hash of it was the casting of the Horse. Having completed the clay model, the last step was to produce the final statue in bronze.

Leonardo certainly knew the process for casting bronze. His teacher Verrocchio was probably the most accomplished master of the art in Europe. But once more it seems Leonardo's - quote - "love of expriment" - unquote - was going to cause problems.

How NOT to Cast Bronze

(Despite What Some People Tell You)

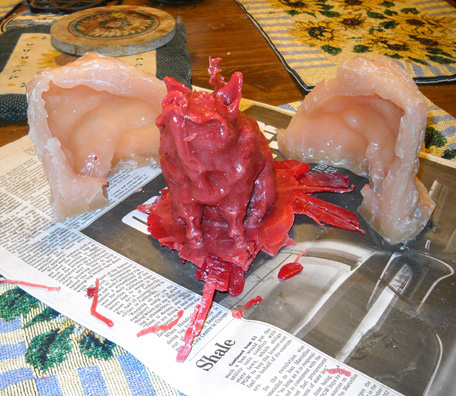

Make the sculpture in clay (thanks to Benvenuto Cellini).

Coat Sculpture with wax and add metal pins.

Add sprues and pour cup (all in wax).

Add shell (clay or plaster mixtures).

Heat the shell to melt the wax leaving hollow mold.

Plug the wax run-out holes and pour in the bronze.

Break off the shell.

Remove the pins and sprues and voila! ...

??????

!!!!!

?????

You have to be careful when reading about bronze casting because even authoritative sources - although we will not name names - get it wrong. For instance, in one popular series of books you read that you first make the sculpture in clay. This is the "original" sculpture and from this you make the bronze cast. This part is true.

But then the - quote - "authoritative source" - unquote - states that you then coat the model in wax. You hold the wax in place with metal pins, and then cover the wax coated model in plaster. So you now have the clay statue covered by a layer of wax covered by a hard plaster shell.

Next you heat the shell and the wax runs out through holes made for that purpose. Hence this casting method is termed the "lost wax" or cire perdue process. And once the wax is out of the shell, you now have a mold where the empty spaces are in the shape of the sculpture.

Now you pour the molten bronze into the shell. The bronze fills the empty spaces, and after the bronze solidifies you break away the shell to reveal a bronze statue. In some descriptions you may learn that you leave the wax in place and the molten bronze melts the wax as it flows through the mold.

There are some problems - big problems - with the method as described. For one thing it won't produce the sculpture that you made in clay. Remember according to this description, you're covering the clay model with the wax. Therefore the details of the clay model will be on the inner side of the bronze cast. Instead, what you'll get is a bronze statue of the clay model covered up in wax.

And if you leave the wax in the mold when you pour in the bronze? Well, in the first place if the wax is still in the mold that means the temperature isn't much above room temperature. So the bronze will freeze before it gets very far in the shell. You'll end up with a plugged up mold and no statue. Instead before you pour in the bronze the shell has to be heated and heated hot.

But if you did manage to have the molten bronze - at 2000 degrees - actually "burn out" the wax, you'd probably blow the mold apart and with it your studio. As we'll see the actual process of bronze casting is a quite a bit more involved than the above descriptions and that may be the reason why you get the abbreviated, albeit incorrect, process described in books and in lectures.

So how, then, do you make a bronze statue?

Well, one way is to make the original statue out of wax, not clay. Since bronze statues of any size need to be hollow, you would fashion the wax sculpture around a clay "core", that is, a roughed out shape of the statue. Then you add a wax coat about 3/8 inch thick and add the details of the sculpture in the wax. NOW you have a hollow wax sculpture over a clay core.

From here on out you do follow the procedure as described. You encase the wax with the plaster to make the shell. Once you let the shell dry thoroughly, you heat it up and let the wax melt and flow out. At this point you have a plaster shell around a clay core with the empty space in the shape of the wax statue. Pour in the bronze, let it solidify and cool, and then knock off the shell. Hey, presto!, you have the bronze cast of the wax sculpture - with the details on the outside where they ought to be.

Although this method - called the "direct" method - was common in the Middle Ages and early Renaissance it is not used that much today since the process destroys the original sculpture. Instead sculptors like to keep the original model on hand to make more bronze casts if need be. So most bronze casting is by what's called the "indirect" method.

For indirect casting you do start off with a finished model. It can be made out of whatever you like. You can make the model out of wax - like Edgar Degas' Little Dancer and his famous horse sculptures - but usually most artists prefer water based clay although sometimes oil based "modeling" clay is used.

But now you don't cover this model with wax. Instead you make a mold directly onto the model. Today such molds are made of rubber - either polyurethane or silicone - which you then encase in a rigid outer mold (called the "mother mold") to hold the rubber in the proper shape. But in Leonardo's day all molds were made out of plaster.

Molds of the statues are made in pieces so you can remove the model. The rigid plaster molds are a particular problem because they can "lock" onto the model. That's less of a problem with rubber molds which sometimes can be made as a single piece. These "sleeve molds" are removed simply by peeling off the statue.

On the other hand, plaster molds - sometimes still used today - have to be made in at least two pieces that can be separated from the model. But for a two piece mold, the sculpture has to be pretty simple - like a portrait bust. Plaster piece molds made for large and complex sculptures sometimes have hundreds of pieces.

It's possible to make a clay model and then make a removeable plaster piece mold directly from it. There are problems though with using a clay model. Unless fired to form terra cotta, clay is not really a permanent medium. It can absorb moisture and can soften and crumble. Worse, if you put wet plaster around an air-dried clay model, the clay will absorb the water and soften. Likely it will fall apart when removing the mold.

Instead the option is to make a more permanent model in a convenient but durable material. Today that might be hard plastic resins. But before the 20th century the model would be made from plaster. A plaster model lasts for years, decades, or centuries even. And if a plaster model breaks, you can make repairs fairly easily. It's this plaster or resin model that's really the "original" sculpture.

But although you could make a plaster model using a piece mold, a simpler procedure is to make a one-time "waste mold". A waste mold is fashioned around the clay model in only a few parts - maybe only in halves - even for a complex model. It doesn't matter now if the mold locks around the model because the wet plaster will soften the clay and you can separate the two halves easily and dig out the wet clay which you can then recycle.

Now here is an incidental but important step. You coat the inside of the mold with a release agent and reassemble it. Today the mold release is typically a silicone liquid spray - but in Leonardo's day it would have been vegetable oil dissolved in some solvent or perhaps a very thin layer of wax. Without the release agent the mold will stick to the model.

At this stage you reassemble the mold, tie it together, and pour in liquid plaster. You let it set - yes, the word is "set" not "sit" - for at least a day. Now you have a solid plaster model locked inside a solid plaster mold that you can't take apart.

Hm. So now what do you do?

Simple. Just take a chisel and placing it at a low angle and making sure the it won't actually touch the surface of the model, you gently chip away the outer mold. Because of the release agent, the plaster of the mold and the plaster of the cast don't bond. So with care, chipping away the mold doesn't hurt the statue.

Making plaster casts is itself an art requiring skill and training. In fact many sculptors don't make their own plaster models but hire expert practiciens to do the job. Even the great Auguste Rodin didn't make his own plaster casts and once he wasn't able to submit a sculpture to the Paris Salon because he didn't have the money on hand to have a plaster cast crafted by the professionals.

The plaster model is kept around until the decision - and the funds - are available to make the bronze sculpture. And just as the artists don't often make their own plaster models, artists almost never do their own bronze casting.

And starting from the plaster model, just how do you make a bronze cast?

Well, the first step here is to make a brand new mold. Yes, you make a mold again. As we said, most molds are made of rubber, but if you know what you're doing you can still make a plaster piece mold without breaking the model.

Once you have the mold - whether plaster or rubber - now you create the wax cast of the sculpture. After spraying on the release agent - never forget this step - you now coat the inside of the mold with a layer of the wax. There's different ways to do this. If the mold is in pieces you can just brush the melted wax onto the inside surface. Or you can assemble the mold and pour in the melted wax, slush it around to coat the inside, and pour out the excess. You continue with the brushing or slushing until you get your wax coat of about 3/8" thick.

Bronze Casting of the Heroic Pigs for the Everlasting Glory and Honor of the House of Sforza

How It's REALLY Done

Clay Model

Clay Model with Inner Rubber Mold and Outer Plaster "Mother" Mold

Wax Layer from "Slushing" In Reassembled Mold

Hollow Wax Cast and Rubber Mold

Final Wax Model

Wax Model in Ceramic Shell

(Sprues and Pour Cup Added)

Bronze Cast Out of Shell

Final Bronze Sculpture with Patina

Viva la Casa Sforzesca!

Now you remove the wax model from the mold - which should be easy if you didn't forget the release agent. What you have now is a wax copy of your original sculpture with all the details on the outside where they should be. If the wax model was cast in separate pieces they can be assembled into a whole (and hollow) statue. Or you can just leave them as separate pieces for the casting. In all cases you need to add wax "sprues" and "gates" to the model before creating the shell so air won't get trapped in the mold and so you can pour in the bronze.

The next step is to make the shell - that is, the mold that will stand up to the 2000 degrees Fahrenheit of the molten bronze. You can do this in a variety of ways. One is to dip the wax pieces into a special colloidal ceramic suspension that dries around the wax. After multiple dips you have a thick shell. Melt the wax, let it run out, and now pour in the bronze.

After the bronze cools, you then break the shell off with a hammer and you cut off the sprues and file any stubs or rough spots down. If the casting was in pieces you put them together with rivets or welding. Then you can polish the metal to remove any residual shell or dirt - modern casting uses sand blasting - and put on a patina which is done by adding certain chemicals to the surface.

Before modern colloidal silica formulations were available, the foundries had other ways to make the shells. Since the shells were destroyed, the material had to be cheap and one procedure called for mixing clay, sand, hair, and animal dung. If the wax model was hollow you would fill it with the shell material and let it dry before driving pins through the wax to give the added support.

At this point the discerning reader may wonder, just what do you do with the "core" after the casting? Well, you simply have to dig it out which can be a long tedious and frustrating experience. In fact, the difficulty of removing the core is one reason so many statues are cast in pieces. Today removing the core is made easier with power tools and sand blasting. In the worst case scenario, sometimes you just leave the core in the statue.

To see a step-by-step introduction on making a wax model just click here. And to see some actual bronze casting click here.

A final method of bronze casting goes back thousands of years. That's sand casting and is the simplest method if one is skilled in the technique but it's virtually impossible for the beginner. It is still used today in professional foundries as it has the advantage that it skips making a wax model altogether.

In sand casting you pack sand into rectangular wooden frames, essentially a box which doesn't have a top or bottom, only sides. Naturally the sand has to be prepared with added water and clay binders to help hold its shape. But once it's all properly packed, you press the piece you want to cast into the sand so it's about halfway below the surface. Then you dust talcum powder over the surface.

The next step is to place another wooden frame on top and pour on more moist sand and pack it down. What you have now is the sculpture sandwiched between blocks of wet sand held in place by two wooden frames one on top of the others. So what do you do now?

Why, you take the sculpture out, of course!

By carefully separating the two frames and removing the model, the sand will remain in place (the talcum powder was to prevent the the blocks of sand from sticking together). You now have two frames of wet sand and each has a partial impress of the sculpture. When you reassemble the frames but without the sculpture, you leave a cavity in the shape of the model inside the sand. Of course, before the reassembly you also create grooves to pour in the bronze and serve as vents to let the air out.

It's hard to believe but pouring 2000 degrees molten bronze into a moist sand mold actually works although the mold is usually buried in sand as a precaution. Then when the bronze cools and after a wack or two, the sand falls away. Now you've hAVE your bronze parts or even the whole statue.

Still, you can see difficulties with sand casting. Since it literally makes the mold from moist sand, a bump here or there can make the packed sand crumble before the casting and you have to start over. Also placing cores to make hollow statues isn't simple, and so sand casting isn't something for the beginner. But the advantage of sand casting is you don't need to make a wax model and best of all, sand casting is relatively cheap.

Sand casting would probably have been the best method of Leonardo to cast his Horse. But from his notes we know he was going to stick with the lost wax process. Apparently Leonardo decided not to cast the sculpture in separate parts and then rivet them together. Instead he was going to cast the horse in one piece. Unfortunately with a one-piece 24 foot sculpture, it would have been virtually impossible for 75 tons of bronze to flow through the entire mold without something going wrong. Had Leonardo gotten that far, the bronze horse would have been another of his failed experiments.

Certainly his plans weren't very reassuring to Duke Ludovico. Having seen Leonardo in action, Ludovico was starting to worry that the famous expert in everything didn't know what he was doing. Worse, leaving Leonardo to his own devices might mean the horse would never be cast.

At first Ludovico wasn't even sure Leonardo could get started. In 1489 he wrote to Lorenzo di Medici, who was still the ruler in Florence, asking to send some skilled and experienced sculptors to Milan. As the Florentine ambassador, Piero Alamanno, wrote in the letter:

Since His Excellency would like to make something truly superlative, I was advised by him to write to you and to ask you to send him one or two artists from Florence who are accomplished in this field. For although the Duke has commissioned Leonardo da Vinci to do the work, it seems to me that he is not confident that he knows how to do it.

But the problems weren't all Leonardo's fault. Five years later, in 1494, Ludovico had decided to help the Duke of Ferrara bolster his defenses and gave him all of the bronze allocated for the Horse to make cannons. In fact, it was in compensation for snitching the bronze that Ludovico had given Leonardo the commission for The Last Supper.

So things dragged on and by 1499 the bronze horse was yet to be cast. By then the French had aligned themselves with Venice (who never liked Ludovico) and invaded Milan. The Duke high-tailed it out of town but was captured and taken to France. Sure, like a lot of high-profile prisoners he was given the freedom of the castles and the surrounding land, and he could even go fishing whenever he wanted.

At that point the usual procedure would be for some of Ludovico's friends or family to pay a hefty ransom to let him go free. But it seems everyone in Italy was glad to have Ludovico out of the way. So he stayed in France as a prisoner. Then in the last year of his life, he began showing signs of going nuts, and he was confined to a dungeon at the Château de Loches where he died in 1508.

The Horse, though, was no more. The model was used as target practice by the French soldiers when they first entered Milan. It ended up as lumps of clay on the ground.

So what art projects did Leonardo do for Ludovico? It doesn't seem like much: a portrait of Ludovico's girlfriend Cecilia Gallerani, a bronze horse that was never made, and The Last Supper for the monks' dining room. You wonder how Leonardo actually got by.

Well, Leonardo did more than just create unfinished paintings and not cast bronze statues. He had some projects with pretty definite deadlines. He would work on architectural designs, create theatrical scenery and costumes, organize entertainments for parties and weddings, and do some interior decorating.

Yes, Leonardo was an interior decorator. In the Duke's castle, Leonardo was often charged with decorating rooms, including one called the Sala delle Asse which no one can decide if it means the "Room of the Tower" or the "Room of the Wooden Boards". Leonardo painted the room to look like it was a vine and tree shaded garden with leaves and branches covering the walls and ceiling. And no, he didn't paint in fresco, but as usual he used tempera and oils. In later years when the French invaded Milan (again) they painted over the room in white paint. Leonardo's designs - including his monochrome underdrawings - were revealed only in the mid-1890's during restoration work. A second restoration was undertaken in the 1950's followed by a third in 2006.

Renaissance rulers loved pageants and theatrical entertainments and so managing these gave Leonardo extra employment. The most famous of his stage productions was La Festa del Paradiso (sometimes just called il Paradiso) a musical with the libretto by the poet Bernardo Bellincioni (pronounced ber-NAHR-doh bell-in-CHOH-nee). Leonardo designed the set where actors played orbiting planets but other than that brief description, we don't know exactly what the production looked like. The mini-series with Philippe depicts a reconstruction of the pageant which the narrator cautions is hypothetical.

So it wasn't always Leonardo's fault that he didn't finish projects. Ludovico would sometimes yank him away from the more artistic endeavors for the mundane tasks. Such diversions tended to irritate Leonardo, particularly since from what we glean from his notes he wasn't always paid regularly (once he beefed that he hadn't been paid in two years). But all of this came to an end when Ludovico was captured by the French.

So now what was Leonardo going to do?

There wasn't much he could do except leave. So in 1500 Leonardo began a wandering and even unsettled life. Selling everything he couldn't take with him, he and his assistants including Salaì and Francesco Melzi traveled about 80 miles east of Milan to Mantua. During his brief stay he drew a chalk portrait of Isabella D'Este who ruled the small principality with her husband Francesco Gonzaga. She said she'd really like a portrait in oils and Leonardo said he would be happy to do so when he got set up in his new studio. The drawing has indications that it was transferred to a panel, but whether he started much less completed the painting is doubtful.

After waiting a while and not getting her painting, Isabella asked a Carmelite monk, Fra Pietro da Novellara, to act as her agent and to bug Leonardo about it. Pietro's correspondence to Isabella has an exasperated tone and gives us a picture of Leonardo the Maestro Piddler. At one point Fra Pietro wrote, "From what I understand Leonardo's life is extremely irregular and haphazard, and he seems to live from day to day. Since he has been in Florence he has only done one drawing in a cartoon. He has not done anything else, though two of his assistants make copies, and he from time to time adds some touches to them. He devotes much of his time to geometry and has no fondness at all for the paintbrush."

Finally Isabella said to heck with it, she'd get Tiziano Vecelli - better known to English speakers as Titian - to paint her portrait provided he'd make her look 40 years younger.

More recently an oil portrait has been discovered that seems to have been based on Leonardo's chalk drawing. Sometimes referred to as a "disputed" Leonardo painting, if Leonardo did paint it, it must have been a bad day.

After leaving, Mantua Leonardo headed to Venice. Since Venice was being threatened with invasion by the Turks, he seems to have again touted himself as a military engineer where he proposed enclosing sailors in leather outfits with a hood with a glass visor. They could go underwater and breathe through a bamboo tube that extended to the surface. Better still, they could carry their own air in an inflatable bag and even have their own - ah - "receptacles" so they could take a welcome break and not bespoil the good sea. Then they would walk along the bottom of the ocean and cut holes in the enemies' ships. Venice's military authorities thought the idea was crazy and so Leonardo returned to Florence before the end of 1500.

Back in his hometown Leonardo further solidified his reputation for not finishing anything. He was hired by the monks at Santissima Annunziata to paint a picture of Mary and her cousin Anne. And yes, he did make a preliminary drawing - which is probably the "cartoon" that Fra Pietro referred to - and is in the National Gallery in London. But he never started, much less finished the painting.

It was also at this time that Leonardo began a painting that Vasari tells us was commissioned by Francesco del Giocondo and was a portrait of his wife, Lisa. But after four years, Leonardo hadn't finished this painting either, no doubt to the chagrin of Francesco and Lisa who had probably made a nice downpayment.

The Mona Lisa is without doubt the most famous painting in the world and is hailed as the ultimate artistic masterpiece. However, this wasn't always the case. Before 1911 it was simply one painting out of many hanging on a wall in the Louvre and wasn't very popular. People passed it by with scarcely a glance.

Then one of the Louvre employees, Vincenzo Peruggia, slipped the painting under his coat and walked out with it. An inside job wasn't suspected at first. Instead the gendarmes questioned a Spanish chap who liked to paint both eyes on one side of a person's head. But it turned out that Pablo Picasso, like Sergeant Schultz, knew nothing and was allowed to go about his business. The Mona Lisa was missing for two years before it was recovered and became the world's greatest painting.

Finding there wasn't much of a market in Florence for unfinished paintings, Leonardo left the city and again got a job as a military engineer with - and this is weird - Cesare Borgia. Cesare is one of the really bad guys of Renaissance Italy even though he was a former cardinal and the son of the Pope, Rodrigo Borgia, who took the moniker Alexander VI. Leonardo only stayed with Cesare for a year and returned to Florence in 1503.

It was at this time that Leonardo was given the commission to paint the Battle of Anghiari which as we said before he didn't complete. But right after the fiasco, Leonardo got a message from the French governor of Milan, Charles d'Amboise, inviting him to return. Leonardo's departure irritated the officials of Florence who had been paying him good money.

The city fathers informed Leonardo in no uncertain terms that they expected him back fairly soon - in fact they stipulated that his absence couldn't go beyond three months. So they became really disgruntled when the King of France, Louis XII, told them they wanted Leonardo to remain in Milan indefinitely. After some negotiations, the permission was granted but rather grudgingly.

From here on out Leonardo was persona non grata ultissima in his old hometown. When he briefly returned to Florence to handle some inheritance issues with his half-brothers, instead of getting the expedited hearing requested by Charles d'Amboise and King Louis XII, he was pretty much given the cold shoulder by the Florentine officials. After months of cooling his heels in Florence, he finally returned to Milan with the inheritance issues still unresolved.

Charles d'Amboise died in 1511 but that didn't seem to make much of a difference for Leonardo. He remained in Milan for a couple of years more. Then one of Lorenzo de Medici's sons, Giovanni, became Pope Leo X, and his brother Giuliano suggested the artist drop by Rome.

So Leonardo again relocated. And it was in Rome that Leonardo was able to continue his serious study of anatomy by chopping up dead people.

One of the biggest myths of our modern era - rivaling the myth that everyone thought the world was flat until Columbus made his voyages - is that dissection was illegal and banned in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. This is not true at all. Autopsies were carried out openly and above board and are documented in Italy as early as 1286. They were no more forbidden than the normal embalming processes which at that time was simply gutting the body to slow down decay. Dissections became quite popular as entertainment and were even held in churches to capacity audiences.

What confuses a lot of people to believing dissections were banned was what happened to Leonardo when he was in Rome. He was not doing much painting at that point. Instead he was carrying out scientific experiments which included the anatomical studies.

Then suddenly Pope Leo ordered Leonardo to cease his dissections. And most people think this meant that the Pope was simply enforcing the church policy against dissection.

But the Pope did not ban dissection per se. Instead his order was directed specifically at Leonardo. Leonardo had been having a professional dispute with a craftsman he had hired to help him prepare mirrors possibly for work on building a solar furnace or as some think for making a reflecting telescope. The worker (called Giovanni although he was German) evidently spread some kind of rumors about Leonardo and his dissections.

One theory is the workman had accused Leonardo of practicing sorcery. But a more recent historian has postulated that Leonardo's studies led him to believe that an unborn fetus had no soul and no separate identity from the mother. Even at that time such a belief was against Catholic doctrine, and the most expedient way for the Pope to quash any rumors, whether about sorcery or heresy, was to tell Leonardo to cut it out (once more, no joke intended).

With Leonardo spending his time chopping up dead people and working with mirrors, Giuliano was beginning to doubt that he was getting his money's worth. At one point he asked Leonardo if he could find time to squeeze in a painting. Of course, Leonardo readily agreed, no problem.

After some months Giuliano asked how the painting was coming along. Great, said Leonardo. Why, he had actually finished distilling the oils needed for making the varnish! When Leo heard of Leonardo's progress, he exploded. "The man will never accomplish anything!" he spluttered. "He thinks about the end of the work before he even begins!"

Once more Leonardo seems to have worn out his welcome. But where to go? With the city fathers of Florence still chaffing about paying for a painting that was never finished and left a mess in the city hall, that city was out. Nor could he expect much business in Venice.

So that pretty much left a return to Milan as the only option. At least there Leonardo owned some property and a vineyard. Except for a brief hiatus, the French were still in charge, and in 1516 Leonardo returned to Milan bringing with him Lisa's portrait.

Almost as soon as he got there, Leonardo got the invitation from the young King Francis I to come live in France. The offer seems to have been simply a kindly offer to a man whom the King admired. It would be hard not to accept which is what Leonardo did.