Mike Seeger

(With a Discussion of the Theory of the 12-Tone Chromatic Scale, Where to Place the Frets on a Fingerboard, and a Little History of the Banjo Thrown In)

"Few people have heard of Mike Seeger...

- Recent Article

Ha? (To quote Shakespeare.)

Few people have heard of Mike Seeger?

Pshaw. Everyone's heard of Mike Seeger. Mike, of course, was the younger brother of Pete and Peggy Seeger. And everyone knows that Mike achieved great distinction independent of just being related to Peggy and Pete.

The Seegers were a musical family. Pete, Mike, and Peggy all became performing professionals. Charles, their dad, was a musicologist teaching at places like Julliard (then called the Institute of Musical Arts) and Berkeley (whose music department he headed). The former Ruth Crawford - Mike and Peggy's mom and Pete's stepmom - was a composer in the modernist vein and was the first woman to receive a Guggenheim fellowship for composition. Pete's mom, Constance, was a violinist and Julliard faculty member.

The Seegers were not an Ozzie and Harriet family (whoever they were). Charles's politics listed a bit off-center, and he was outspoken against America's involvement in World War I. A tendency toward pacifism carried through the family, and it did get Charles into hot water from time to time.

In fact, Charles's pacifism got him booted out of Berkeley. To make ends meet he sometimes had to work on his parents' farm in Patterson, New Jersey, and he even had to borrow money from his older sons (and Pete's older brothers), John and Charles.

You read two stories about Mike's interest in music. On the one hand, you'll hear that Mike became fascinated by folk music when just a young kid. He even made a recording when a pre-teen.

But others remembered the young Michael as quite indifferent to the arts. Peggy once said their parents gave Mike a choice of daily tasks. Either he could learn to play a musical instrument or he could take out the garbage. "Mike preferred to take out the garbage," she said.

But when he was eighteen Mike came down with shingles on his eyes which required him to lie for weeks in a darkened room. So his mother challenged him to learn the banjo.

With Peggy reading to him from Pete's instruction book, Mike would lie in bed and play through the lessons. By the time he recovered it was clear he had inherited the Seeger talent.

By the early 1950's Mike had decided to make music his career but wasn't clear how he was going to be someone other than Pete Seeger's younger brother (by 1950 Pete already had an international reputation). But he was able to learn other instruments easily (Pete always said Mike was the best musician of the family) and was soon playing not just the banjo, but the guitar, fiddle, mandolin, autoharp, dobro, dulcimer, guitar, mouth organ (harmonica), and jaw harp. He even played the pan pipes, for crying out loud!

Living in or near New York, Mike naturally gravitated toward Greenwich Village (in fact, the family had lived there for a while). Although this was the Beat Era, there were other types of counterculturists in New York. And starting in the 1950's there were kids who had picked up guitars and banjos and began performing folk music on the streets and even in the clubs.

Mike became part of the folk scene and in 1958 he joined up with two friends, John Cohen and Tom Paley, to form the New Lost City Ramblers. The name was taken in part from the Old Timey group The North Carolina Ramblers. This popular group was led by Charlie Poole1 from 1925 until his premature death in 1931. Charley had more influence on modern country and folk music than many fans realize.

Footnote

Anyone who doubts the influence of Charlie should listen to the early records of urban folk singers. That many of then were deliberately trying for Charlie's sound isn't to be denied.

Many of these "urban" folk singers were laying the groundwork for what would later be called folk rock. The folk rockers included the likes of Simon and Garfunkel, The Byrds, The Mamas and the Papas, the Lovin' Spoonfall, Donovan, and even a future winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature. Although the songs of the folk rockers were often called folk songs, strictly speaking they were not.

But what, you ask, is a folk song? Certainly there are wishy-washy definitions that will include folk rock or almost anything with acoustical instruments. But the fundamental definition is a bit more specific:

folk song: a song originating among the people of a country or area, passed by oral tradition from one singer or generation to the next, often existing in several versions and generally by simple, modal melody and stanzaic, narrative verse.

Of course there are many types of folk music. But what Mike, John, and Tom (who in a couple of years was replaced by Tracy Schwartz) wanted to play was the music of the Anglo-European settlers of the Appalachian mountains. That is, they wanted to play Old Timey Music as it had really been played when it wasn't Old Time. To further the cause, they began appearing at folk festivals and in concerts and began recording for Moe Asch's Folkways label when Moe was still recording directly to disk.

Moe Asch

Recording directly.

The origins of the term Old Timey or Old Time Music are lost to history and are confounded by the use of "Old Time Music" to refer to any music from the past (a magazine in the 1890's mentioned "old time music" was from the 1700's). But in the sense of being indigenous "string band" music from the Appalachian Mountains, the term was in colloquial use by the 1920's. In one of the skits recorded by the Skillet Lickers in 1929, fiddler Clay McMichen told the rest of the group that he was going to show them what "real Old Time fiddlin' is".

The New Lost City Ramblers began playing during what was the second Folk Music Revival. There were arguably three. The First Revival began in 1940 at the "Grapes of Wrath" concert in New York City where Woody Guthrie appeared for his first nationally publicized performance. This was also when we saw the rise of other icons like Burl Ives and (of course) Pete Seeger.

Big Brother Pete ...

... Burl ...

...and Woody

The First Revival

The high point of the First Folk Revival was when Pete, Ronnie Gilbert, Lee Hayes, and Fred Hellerman banded together as The Weavers. In 1950, one of their songs, "Goodnight, Irene" - which was a somewhat sanitized version of Leadbelly's "Irene" - reached #1 on the Billboard Charts.

But the First Folk Revival faded due to the McCarthy Era blacklisting (Pete and his friends did tend to lean to the left). But Americans didn't know a good thing when they saw it. With folk music falling out of favor, the kids turned to what was then called Rock 'n' Roll. This music - and many parents had doubts that it should be labeled as such - was most notably embodied by the performances of the Young Man from Memphis. Good Americans were horrified.

The Weavers

Pete, Ronnie, Lee, and Fred

The Man from Memphis

Mainstream

Then in 1958 three clean-cut and apolitical college kids under the name of the Kingston Trio had a #1 hit with "Tom Dooley". This song launched the Second Folk Revival which produced songs that were so innocuous that folk music soon had its own primetime television show. Even the parents would sit in front of the television set to watch Hootenanny. But in little more than a year the interest had waned and by 1964 the show was canceled.

The Third Folk Revival got its launch in 1972 when the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band issued its album Will the Circle Be Unbroken? This third manifestation got a major boost since it also corresponded to the Rise of the American Mall and their now vanished institution, the record store. Bins began filling with what had been hard to obtain recordings and these included a lot of disks from Folkways.

Many of the singers from the two earlier revivals got a reboost and in some ways the Third Revival was a continuation of the Second. But whether the 70's saw the Third Folk Revival or the Second Folk Revival Part 2, folk music as an institution carried on well into the 1980's. By then, alas, folk music was soon eclipsed by the rise of Country Music as an entertainment and financial industry that eventually rivaled the power and prestige of Rock which in its many variants became Rock 'n' Roll no more.

Of course, although the True Folk Phenomenon had passed, there were still lots of folk music fans. By 1980 and although he was just in his forties, Mike had assumed the role of the Grand Old Man of Folk Music Scholarship. He had written articles on the history of folk music (and that included bluegrass), was a Visiting Scholar for the Smithsonian Institution, was awarded grants from the National Education Association, and always continued to perform and give lectures. Sadly Mike died in 2009 shortly before his 76th birthday. But Mike will always be remembered for the days with the New Lost City Ramblers.

We have to admit there are differences between the playing of the New Lost City Ramblers and the original string bands of the Appalachians. Critics have pointed out that Mike and the others were not just imitating the old groups but had created their own style. A lot of people liked the New Lost City Ramblers but wondered what was so great about the early groups.

Admittedly there was the musicianship. Although there were certainly virtuosi in the original bands - The Skillet Lickers immediately come to mind - the playing of the early musicians often comes off as rudimentary. For instance, although in the 1920's Charlie Poole played a three-fingered banjo style, it was a far cry from the flashy Scruggs technique (which Earl himself always credited to North Carolina banjoist Smith Hammett). Certainly, early Old Timey singing can be rather stiff compared to the vocals of Mike, John, Tom, and Tracy.

One point to remember is that the original Old Timey music was primarily dance music. So you had to have a tempo that people could dosey-doe to, and so requiring the bands would maintain up a moderate, steady, and "stiff" tempo. You really can't dance to Bill Monroe playing "Bluegrass Breakdown". But you can dance to Charlie Poole singing "Goodbye, Miss Liza".

Mike's banjo playing was particularly notable and he was skilled not only on modern instruments but on the fretless banjo as well. Yes, the earliest banjos had no frets. Instead they were built with a simple flat fingerboard.

Of course, fretless stringed instruments are commonplace. Orchestral violins, violas, cellos, and double basses are modern examples. And some electric basses are made with fretless fingerboards. Lack of frets allows glissandos and slides of the type that are distinct from those on the fretted instruments.

Lest musical historians go onto spittle flinging diatribes and produce illustrations of early banjos with frets, we are specifically talking about banjos made in rural areas where the lack of frets was largely a matter of practicality. If you want to put frets on the instruments you have to place them carefully so that the instrument will be in tune as you play up and down the finger board. Anyone who has looked at a fretted instrument knows that the frets get closer together as you move toward the body of the instrument. Errors of a tenth of an inch can produce discord.

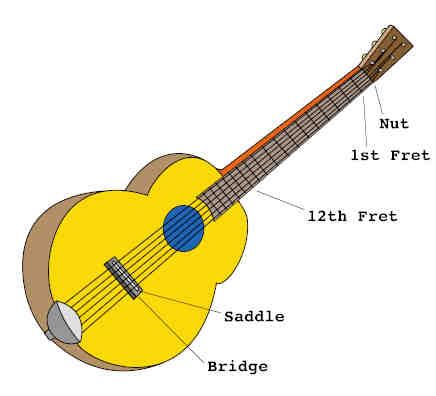

Guitar Parts

The most popular fretted instrument is the guitar and the theory behind the fret spacing is fairly simple and requires nothing but middle school math. Western music - which is what the modern European instruments use - is based on the modes of the Ancient Greeks. These in turn are derived from the 12-tone chromatic scale with twelve equally spaced steps from the first note to the next octave.

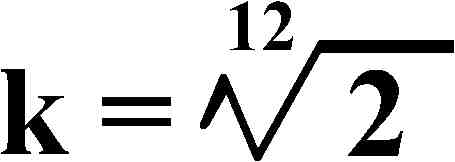

Now here we mean "equal" in the sense that the frequency of a note is related to the subsequent note by a (as yet unspecified) constant. We'll call the constant k.

So if the first note has frequency, ν1, the next note, ν2, is given by the simple equation:

ν2 = ν1 × k

The third note, ν3, is then:

ν3 = ν2 × k

... or ...

ν3 = ν1 × k × k

Now if we want to move up the twelve steps from the first note to the octave this gives us the equation:

νOCTAVE = ν1 × k × k × k × k × k × k × k × k × k × k × k × k

Or more succinctly with middle school math:

νOCTAVE = ν1 × k12

Now remember from music theory that if we have moved up an octave, we have doubled the frequency. So we have:

νOCTAVE = 2ν1

... and ...

νOCTAVE = 2ν1 = ν1 × k12

... or more simply:

2ν1 = ν1 × k12

... and canceling out the ν1's...

2 = k12

... and hey, presto!

k = 21/12

Or if you don't like fractional exponents:

.. . and if you don't like exponents at all:

k = 1.0594630944

So if we have an A scale starting at 440 cycles per second (called 440 hertz), the next half-tone up, which is A#, is:

ν2 = 1.0594630944 × ν1

... or ...

A#5 = 466.2 Hz

The next note, B4, is:

B4 = 446.2 × 1.0594630944

= 493.9 Hz

And the chromatic scale from A4 to A5 is:

| Step | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1 | A4 | 440 |

| 2 | A#4 | 466.2 |

| 3 | B4 | 493.9 |

| 4 | C5 | 523.3 |

| 5 | C#5 | 554.4 |

| 6 | D5 | 587.3 |

| 7 | D#5 | 622.3 |

| 8 | E5 | 659.3 |

| 9 | F5 | 698.5 |

| 10 | F5# | 740 |

| 11 | G | 784 |

| 12 | G#5 | 830.6 |

| Octave | A5 | 880 |

Of course if you go down the chromatic scale, then, you divide by 1.0594630944.

Each step of the chromatic scale is called a half-step. So two steps are a whole step on the diatonic scale which have various "keys" or more accurately are the modes of Western music. For instance the A-Major scale is:

| Step | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1 | A4 | 440 |

| 2 | B4 | 493.9 |

| 3 | C#5 | 554.4 |

| 4 | D5 | 587.3 |

| 5 | E5 | 659.3 |

| 6 | F5# | 740 |

| 7 | G#5 | 830.6 |

| 8 (Octave) | A5 | 880 |

What's nice is that the equation for the chromatic scale translates quite nicely to placing frets on a fingerboard. When you have a string stretched between two points, then you produce the octave by dividing the string in half. So the physical locations for pressing the strings calculated from the same constant used to determine the frequencies of the scale.

Because strings must be shorter as the notes go higher, you must divide the lengths by k to get the next higher note. So the equation is:

Fn+1 = Fn ÷ 1.0594630944

... where:

| Fn: | |

| Fret n + 1: |

Or if you don't like dividing you can use:

Fn+1 = Fn × 0.9438743127

A slightly modified equation - which the reader can easily derive for themselves - is:

Fn+1 = D - Fn × 0.9438743127

... where:

| D: | (Distance from the nut to the bridge saddle) |

| Fn: |

Hence for a guitar with a 25.52 inch scale - the scale is the distance from the "nut" to the bridge saddle - this becomes:

Footnote

Scale lengths vary depending on the type of guitar. Smaller guitars can have scales as low as 24 inches. The classical guitar usually has a long scale of 26 inches.

Fret #1 = 25.5 × 0.9438743127 = 24.07 inches

So the distance from the 1st Fret from the nut is:

Fret #1 = 25.5 - 24.07 = 1.43 inches.

For Fret #2 we get:

Fret #2 = 25.5 × 0.9439 = 22.72 inches

...for the distance from Fret #2 to the saddle.

And the distance from the 2nd Fret from the 1st fret is:

Fret #1 = 24.07 - 22.72 - 1.35 inches.

And as you go down the line:

(25.5 Inch Scale) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Fret | Saddle | Previous Fret |

| Nut | 25.50 | 0.00 |

| Fret 1 | 24.07 | 1.43 |

| Fret 2 | 22.72 | 1.35 |

| Fret 3 | 21.44 | 1.28 |

| Fret 4 | 20.24 | 1.20 |

| Fret 5 | 19.10 | 1.14 |

| Fret 6 | 18.03 | 1.07 |

| Fret 7 | 17.02 | 1.01 |

| Fret 8 | 16.06 | 0.96 |

| Fret 9 | 15.16 | 0.90 |

| Fret 10 | 14.31 | 0.85 |

| Fret 11 | 13.51 | 0.80 |

| Fret 12 | 12.75 | 0.76 |

| Fret 13 | 12.03 | 0.72 |

| Fret 14 | 11.36 | 0.68 |

| Fret 15 | 10.72 | 0.64 |

| Fret 16 | 10.12 | 0.60 |

| Fret 17 | 9.55 | 0.57 |

| Fret 18 | 9.02 | 0.54 |

| Fret 19 | 8.51 | 0.51 |

| Fret 20 | 8.03 | 0.48 |

The point to note - no pun intended - is that the 12th fret is exactly halfway between the nut and the saddle. So the 12th fret marks the octave.

Now an Appalachian luthier would know how to calculate fret distances and would even have a template that he would place over the fretboard so he could saw the grooves for the frets at their proper places. On the other hand, an Appalachian farmer from the 1870's probably would not have the resources to make a fretted instrument.

Examples of original 19th century Appalachian banjos are extant. One instrument from the last quarter of the 19th century was bought in an old shop and repaired by North Carolina farmer and woodworker Frank Proffitt whose singing of "Tom Dooley" formed the basis of the Kingston Trio's hit tune. A characteristic of many homemade Appalachian banjos is they have a small diameter but a thick rim with the skin attached without a tension hoop and hooks. The tuning keys are usually simple friction pegs and the strings can be metal or gut (which today are usually replaced with nylon3).

Footnote

Pressing the strings on the frets or fingerboard tends to distort the shape slightly. The tension on the strings also stretches them to produce slightly smaller diameters. So older strings tend to play increasingly our of tune and must be replaced from time to time to produce the best intonation.

But the lack of frets is not simply because the Appalachian farmers didn't want to bother. Unfretted instruments also are common in other parts of the world, and one indisputable fact is the American banjo has its roots from Africa.

The African origins of the instrument has never been in doubt. Thomas Jefferson even commented on the instrument when writing about his slaves:

The instrument proper to them is the banjar, which they brought hither from Africa, and which is the original of the guitar, its chords being precisely the four lower chords of the guitar.

Tom's comments require elaboration. Although the two instruments may have shared a common ancestor, the modern guitar is not a direct descendent of the modern banjo.

Also when Tom said "chords" he meant "strings" (ergo, "cords"). And although some of Tom's relatives mentioned buying a Spanish guitar, that's not what he meant when he talks about a guitar or its tuning.

Tom's guitar was the ten string English guitar which superficially resembles a lute. There are two single bass strings and four "double course" treble strings. The tuning is usually an open C chord: C4 (Middle C) - E4 - G4 - C5 - E5 - G5 (or in older Helmholtz notation c-e-g-c'-e'-g'). The last four notes are sounded on paired unison strings.

The problem was that Tom didn't tell us whether he meant the four lower strings by pitch or by location. If he meant the four strings lowest in pitch, that would give us C4-E4-G4-C5. But if he meant by location when you're playing the instrument, that'd be G4-C5-E5-G5.

Alas, Tom is probably wrong in either case.

We don't have any pictures of the instruments played by the slaves on Monticello. But there is a painting from the late 1700's from what was probably a North Carolina plantation. The painting depicts a group of slaves dancing while another sits and plays the banjo. The painting renders the instrument in sufficient detail that it was able to be reconstructed.

The banjo of the colonial era was made by attaching a fingerboard to a large calabash "bottle" gourd. The dried gourd is split medially and a skin stretched and tacked into place. Optionally and for fancy instruments, a flat top with a circular cut was placed over the skin. Strings are stretched from the end of the gourd up to the head at the top of the finger board and attached to tuning pegs.

But Tom's descriptions of the "banjar" differs from the painting. He describes the strings as if they are pitched from low to high based on their position. On the other hand the gourd banjo clearly had the fourth string - the "top" string - attached like the fifth string on the modern five string banjo. That is, it is attached to a peg down the neck and so is shorter and higher in pitch than the strings below it.

Gourd Banjo

1780-1790

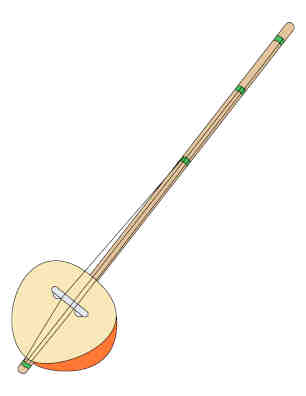

Akonting

West Africa

We said the instrument has its roots in Africa and the West African scholar, Daniel Laemouahuma Jatta, has concluded that the indigenous African instrument closest to the American gourd banjo in construction and playing is the akonting. The akonting is a three stringed instrument with a gourd body and a long fretless neck. The strings are of different lengths with the shorter strings placed at the higher locations. The melody is played on the two longest strings while the shortest third string serves the duty of the drone like the fifth string of today's banjos.

The neck of the akonting is thinner than the banjo's and is often left rounded - like a thick dowel rod - rather than planed flat. The strings on the traditional instrument are simply tied to the neck at the desired lengths to get the different notes. This simplifies obtaining functional strings since they can all be the same thickness (even 50-60 pound monofilament nylon fishing line will work). The akonting is also strung at lower tension than the modern banjo and so is quieter and suitable for indoor playing.

In America the slaves were brought into contact with European instruments and the akonting was quickly modified by the slaves. We see that even in the 18th century the melody strings on the banjo were now the same length and so differed in gauge. The tension was altered using tuning pegs which are also used on more elaborate atonkings. But the shorter drone string was kept. The four string "tenor" banjo was a later development when the fifth string was dropped.

It's too bad that Tom, who had considerable musical training, didn't spend more time studying the music of the slaves. Instead he takes a rather dismissive attitude toward their culture. The book he wrote, Notes on the State of Virginia, makes painful reading for those who look to Tom as a hero in other matters.

Some may question whether the akonting is indeed the direct predecessor of the American banjo. There are after all many similar instruments in Africa, Asia, and Europe. But what gives this theory a real boost is to watch a native West African play the akonting.

Unlike other indigenous stringed instruments, the akonting is played by the "clawhammer" or "frailing" style like the American Old Timey banjoist. You pick the melody with a downstroke using the back of the finger while the thumb picks the drone string usually on the off-beat. This produces a nice plunky sound with a "bump-ba-ba bump-ba-ba bump-ba-ba bump" rhythm. Most other stringed folk instruments are played by regular "finger-picking", with a plectrum (pick), or strummed.

The early banjos were definitely played by the clawhammer method. This is well documented in mid-19th century instruction manuals. One of the most popular was titled:

BANJO INSTRUCTOR:

CONTAINING THE

ELEMENTARY PRINCIPLES OF MUSIC,

TOGETHER WITH EXAMPLES AND LESSONS NECESSARY TO FACILITATE THE ACQUIREMENT OF A PERFECT KNOWLEDGE OF THE INSTRUMENT TO WHICH IS ADDED A CHOICE COLLECTION OF PIECES, NUMBERING OVER FIFTY POPULAR DANCES, POLKAS, MELODIES, &G. &C. MANY OF WHICH HAVE NEVER BEFORE BEEN PUBLISHED COMPOSED AND ARRANGED EXPRESSLY FOR THIS WORK

BY THOMAS F. BRIGGS

BOSTON, : PUBLISHED BY OLIVER DISTON & CO., WASHINGTON ST.

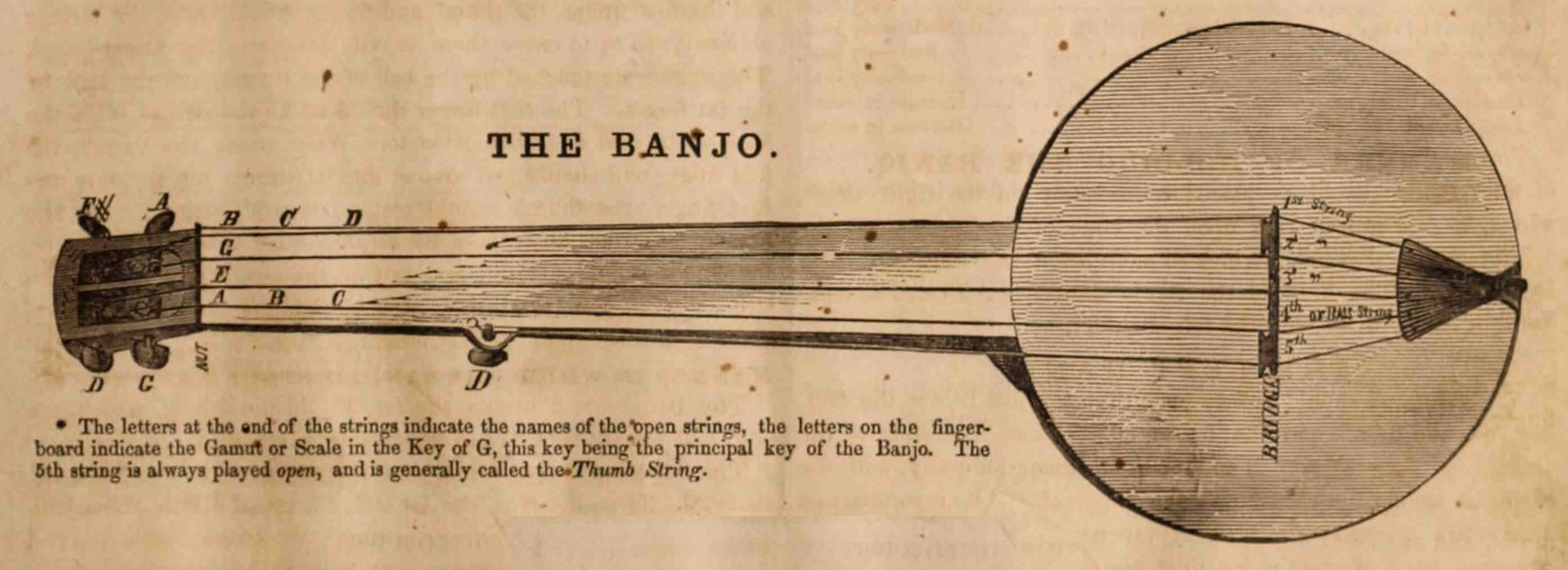

The instrument shown in the manual is essentially the modern 5-string, albeit fretless, banjo. The tuning is specified as tuning was D5 G3 D3 E#4(F4) A4

Banjo - 1855

(Click to open in expandable window.)

In the manual, the only method mentioned for plucking the strings is the clawhammer style or frailing:

MANNER OP PLAYING

In playing, the thumb and first finger only of the right hand are used; the 5th string is touched by the thumb only, this string is always played open, the other strings are touched by the thumb and the first finger, the thumb and finger should meet the strings obliquely, so as to cause them to vibrate across the finger-board. The strings are touched by the ball of the thumb, and the nail of the first finger. The first finger should strike the strings with the back of the nail [italics in the original] and then slide to.

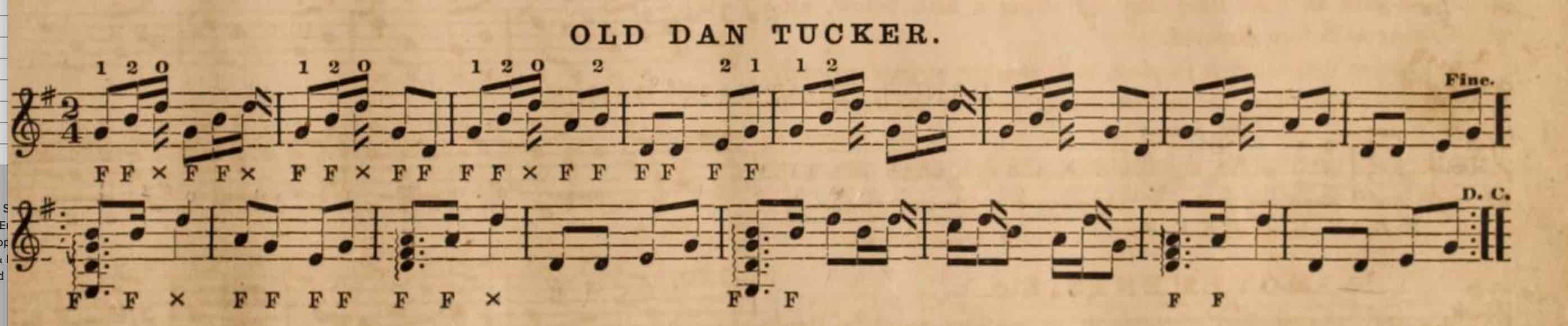

An example of the music from 1855 is the old standard,"Old Dan Tucker".

Old Dan Tucker - 1855

(Click to open in expandable window.)

And to listen to the 1855 song:

Audio File

Old Dan Tucker (1855)

(Sound file created with MuseSCORE)

The manual did not insist that the tuning be exactly as recommended. Even today the banjo has no standard tuning although some are more common than others.

In years past, the most common tuning of the tenor banjo was C4, G4, D5, A5, and this tuning is still used in Dixieland jazz. However, today's Irish musicians prefer to tune each string a perfect fourth lower - G3, D4, A4, E5 - so it is the same as a fiddle. This latter tuning is credited to the master banjoist of the original Dubliners, Barney McKenna (1939-2012).

For bluegrass musicians the most common tuning is G5 (Fifth String), D4, G4, B5, D5. The middle three strings are like those of a guitar but the first string is a step lower than the guitar's E5. If sounded with no fretting this tuning produces a D-major chord. The bluegrass tuning fits well with the rapid single-note playing that some have likened to hearing someone spitting a mouthful of hard beans into a tin can.

Old Timey banjoists who play the clawhammer or frailing style often take the bluegrass tuning but drop the fourth string a step to sound G5, C4, G4, B5, D5. This is called the "C-tuning" and if you press the second fret of the first string and first fret on the second string, you get a C-Chord. This is sometimes modified to what's called the "Double-C" tuning - it has two C's - where you also raise the second string half a step and have G5, C4, G4, C5, D5. Just pressing the second fret of the first string gives you the C-chord.

When playing with a fiddle these tunings are sometimes changed to the "D" tunings by raising each string a whole step: A6, D4, A4, C#5 (D5), E5. Tunings where pressing only one or two strings forms a chord are particularly suitable for Old Timey playing because the frailing downstroke sometimes strikes strings other than the one intended and so preserves the pleasing harmony.

Some have found playing Old Timey music a challenge. But you know what they say about playing clawhammer banjo. If at first you don't succeed, try, try, until you frail.

References

Music from the True Vine: Mike Seeger's Life and Musical Journey, Bil Malone, University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

"The New Lost City Ramblers: 50 Years of Folk", Ray Allen, Smithsonian Magazine.

"Roots and Branches: Forty Years of the New Lost City Ramblers", Philip F. Gura, The Old-Time Herald, Volume 7, Number 2, Winter 1999/2000.

"Mike Seeger", Bluegrass Hall of Fame.

"Mike Seeger", Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

How Can I Keep from Singing?, David Dunaway, Random House, 1981, 2008.

New Lost City Ramblers, Discogs

Bluegrass: A History, Neil Rosenberg, University of Illinois Press, 1985

"Calculating Fret Distances", Samuel Carliles, Whiting School of Engineering, Johns Hopkins University.

"Scale Length", Guitar Guru, June 26, 2015.

"Scale Length Explained", StewMac.

"The Mathematics Behind Fret Spacing", New England Music Store.

Notes on the State of Virginia, John Stockdale, 1787.

"Mike Seeger, Singer and Music Historian", Ben Sisario, The New York Times, August 10, 2009.

"Earl Scruggs and the 3-Finger Banjo Style", Bob Carlin, Banjo NewsLetter, May 2012.

Early Banjo Traditions.

"A Brief History of the Guitar and Its Travel South", Mike Seeger, Carla Borden (Editor), Smithsonian Year of Music.

"What Was Colonial or 'Early American' Music?", David K. Hildebrand, Colonial Music Institute.

"Cittern", Monticello.

The History of the Guitar: Its Origins and Evolution, Júlio Ribeiro Alves, Huntington, 2015.

Banjo Instructor: Containing the Elementary Principles of Music, Together With Examples and Lessons Necessary to Facilitate the Acquirement of a Perfect Knowledge of the Instrument to Which is Added a Choice Collection of Pieces, Numbering Over Fifty Popular Dances, Polkas, Melodies, &g. &c. Many of Which Have Never Before Been Published Composed and Arranged Expressly for This Work, Thomas F. Briggs, Oliver Diston and Company, 1855.

"Historical Narratives of the Akonting and Banjo", Scott Linford, Ethnomusicology Review, July 27, 2014.

"The Senegambian Akonting: The Origin of the Banjo", Daniel Laemouahuma Jatta, Universum i nytt ljus

"Irish Tenor Banjo - What is the Standard Tuning", David Bandrowski, Deering Banjos.

"Tunings", Don Borchelt, Banj'r.

"Classical Guitar String Tensions", Gamut Music.

"Mel's 2019 Fishing Line Diameter Page", Mel's Place.

"Trailblazers: Celebrating Women Composers at Focus 2020", Susan Jackson, Juilliard Journal, Dec 17, 2019.

"Gourd Banjos: From Africa to the Appalachians", Banjo History, November 1, 2001.

The Year's Music - 1896, Being a Concise Record of British and Foreign Musical Events, Productions, Appearance, Criticism, Memoranda, Etc., Albert Charles Robinson Carter, p. 21, J. S. Virtue and Company, 1896

"Night in a Blind Tiger", The Skillet Lickers, County 526.

"Appalachian Music", Library of Congress.

"Fate Norris: 'Night in a Blind Tiger', Columbia W149340/W149341, 11/2/1929, Discography of American Historical Recordings.

"Charlie Poole, 1892-1931", Dictionary of North Carolina Biography, William Powell (Editor), University of North Carolina Press, 1979, 1996 (Reprinted: Documenting the American South.

New Lost City Ramblers: The Early Years, Smithsonian Folkways, Institution, 1991, 2009.

New Lost City Ramblers: 20th Anniversary Concert, Flying Fish Records, 1978.

Random House Compact Unabridged Dictionary, Second Edition, Random House, 1987, 1993, 1996.