Nikola Tesla

The Man and the Inventions(?)

Nikola Testla

The First of All

Here's a story from the Fount of All Knowledge.

It was really the great Serbian physicist and engineer, Nikola Tesla, who invented the radio. Not that rich Italian kid Guglielmo Marconi, who invented absolutely nothing, but still got the big money boys to back his claim that he could send messages across the world. So Nikola ended up dying penniless in a fleabag hotel in New York while Guglielmo got rich and won the Nobel Prize.

But then, after long last, justice prevailed! In the year Nikola died, 1943, the Supreme Court of the United States of America acknowledged that Guglielmo's patents were invalid and restored the rights to Nikola. And so the Highest Court in the Land of the Free and Home of the Brave proclaimed that Nikola Tesla was indeed the inventor of the Radio!

As we said you can read this on the Fount of All Knowledge.

Or you can read what really happened.

Let's start off with the actual Supreme Court opinion. For the majority, Chief Justice Harlan Stone wrote on June 21, 1943:

Marconi's reputation as the man who first achieved successful radio transmission rests on his original patent, which became reissue No. 11,913, and which is not here in question.

Hm. That doesn't sound like they're saying Nikola Tesla invented the radio.

Then Harlan continues:

That reputation, however well deserved, does not entitle him to a patent for every later improvement which he claims in the radio field.

So they were considering if some of Guglielmo's improvements were valid. Not his "well-deserved" reputation as the inventor of the radio.

In fact, the Court was only considering whether one specific patent that Gulgielmo filed, US 763,772, had prior precedence.

And yes, the Court did mention Nikola. But Harlan also cited other inventors and scientists. These were Sir Oliver Lodge, John Ambrose Fleming, John Stone (no relation to Harlan), and the famous Sir William Crooks. All had done work on radio transmission before Nikola.

First suggestion. Don't read what others say about the patents or the Court opinion. Go read the patents, US 645576 (Nikola's) and US 763772 (Guglielmo's), and the opinion, Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company vs. United States 320 U.S. 1 (1943). Nikola's patent, in fact, is about transmitting power for industrial purposes. That is, Nikola's invention is about electrical power without the wires. As far as the opinion, we'll see that Harlan had to really fish deep to say it anticipated Guglielmo's wireless telegraph.

And here's the real surprise. The case was started by Guglielmo. He had claimed that the United States Government had been infringing his patent. So he felt he was owed compensation.

But the judges ruled that his claims - about the improvements - had been anticipated by earlier patents. And so, Harlan said, the US Government owed Guglielmo nothing. Or rather they owed Guglielmo's company nothing. After all, in 1943 Guglielmo was no longer alive. Whether the non-legal issue of Italy being at War with the US in that year was an issue in the Court's decision in an opinion best left to the scholars.

But the opinion didn't deal that much with Nikola's patent. It was mostly about whether Guglielmo's patent conflicted with the one by John Stone.

But here's what's odd. The court said they weren't going to determine if John's patent was actually valid. In fact, because of technicalities of what constitutes prior disclosure, for the court to rule as it did, it didn't matter if any of the early patents - even Nikola's - were valid. So even though they said that one of Guglielmo's patents did not have priority, the Court restored nothing to anyone except the right of the United States not to pay Guglielmo.

In summary then this famous case:

| 1. | Specifically cited and did not dispute Guglielmo's "well-deserved reputation" as the first to send radio transmissions. |

| 2. | Stated that the validity of Guglielmo's original patent establishing him as inventor of the radio was not being questioned. |

| 3. | Dealt only with one later patent for improvements of the radio apparatus. |

| 4. | Said that sound waves were electromagnetic radiation. |

Ha? (To quote Shakespeare.) The Court did what?

Well, just read what Harlan wrote in his introduction to the case:

Hertzian waves are electrical oscillations which travel with the speed of light and have varying wave lengths and consequent frequencies intermediate between the frequency ranges of light and sound waves.

Well, OK. Maybe Harlan didn't say sound waves were electromagnetic waves. But if you do known what electromagnetic waves are, it's clear that Harlan did not.

But did Nikola?

Give Me Those Old Time Inventions

OK. So maybe Nikola did not invent radio. But he did invent other things. I mean, we do read he invented alternating current.

Don't we?

Weeeeellllll, despite what you read even by some science writers and legal scholars who should know better, Nikola did not invent alternating current, not by a long shot. Working AC generators had been around before Nikola was born and by 1886, when Nikola was still working for Thomas Edison, the American, William Stanley, Jr., had demonstrated AC current could provide commercial power for arc lighting.

But there is no doubt that Nikola Tesla had a number of US patents. Many were related to improving alternating current dynamos and motors.

The trouble with who should get credit for what is that Nikola was working in what we call a "crowded field". Lots of people were working on AC multiphase systems. But George Westinghouse learned of Nikola's inventions - Nikola had given well-publicized demonstrations at Columbia University and the American Society of Electrical Engineers - and paid him a cool $60,000 for the patent rights. That's in 1890's currency.

George had also been contracted to supply electric lights - AC of course - to the 1893 World's Fair - the Columbian Exposition - and also to put in hydro-electrical generators at Niagara Falls. After some debate among whose systems to use, George selected designs based on Nikola's two-phase systems and they worked. So clearly Nikola was no dummy.

The success of the Columbian Exposition - the walks illuminated at night by rows of electric lights - and the Niagara Falls hydroelectric plant suddenly made Nikola a household name. He spoke at major universities and scientific and engineering societies. But best of all, he met and befriended the Power Brokers on Wall Street. That is, the men with the cash, the boodle, and the coin.

But did Nikola invent the radio?

Or rather, just what did Nikola Tesla invent?

First off, let's look at what we mean by an invention. For this we need a little excursion into the past.

And we mean the past.

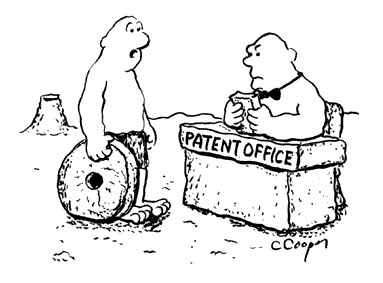

Thork the Caveman suddenly has a great idea. He carves a disk out of a chunk of rock. It's something new, and he takes it to his friendly neighborhood cave dwelling patent examiner. He calls his new invention the wheel.

Prior art? What prior art?

The patent examiner looks at Thork's application. He sees that yes, the wheel is new and novel. But he says to get a patent, your invention must be useful. That is, what good is the wheel?

Well, Thork says, you can stand it on its edge, and you can roll it along the ground. As long as it's moving fast enough, it doesn't fall over. If nothing else it is amusing. So the wheel has utility as an entertainment device. But he hastens to point out, in his patent he mentioned "there are many other applications we can envision for the wheel".

OK, says the examiner, the wheel is new, novel, and useful as an entertainment device and other things. So he grants the patent.

Now in Thork's working model he carved the wheel out of stone. But in his patent he didn't say that. Most importantly at the end of the patent, where he specifies his claims, he mentioned no specific material of construction.

So along comes Oog, another Caveman. He realizes he can make a wheel by cutting down a tree and chopping off the end of the trunk. This makes a disk that can roll along the ground. He points out that the wooden wheel is lighter and easier to make than Thork's stone wheel. So he files a patent for an improvement over Thork's invention.

But Thork objects. Using wood is simply an obvious extension of his patent. Anyone skilled in the art would realize you could make a wheel out of wood as Oog claims. The examiner agrees and Oog does not get his patent.

Oog, though, appeals his ruling. But the patent judges agree with the examiner. Anyone who understood the wheel could realize you could make it out of wood as well as stone. So no patent for Oog's wooden wheel.

But then along come Doog, another caveman. He realizes you can carve out pie-like slices on the inside out of the wheel leaving spokes. It works for a wooden or stone wheel.

So he files a patent for the new improvement. The advantage, he points out, is the new wheel is lighter. But best of all, if the wheel is wood, the spokes add flexibility, and so the wheel doesn't break as often. The patent examiner agrees the modification - the improvement - is new, novel, and useful.

But the examiner points out, there are actually two patents here. One is for a spoked wheel and the other for the spokes themselves. So Doog splits the patent and gets two patents.

However, when Doog starts to manufacture his wheel, Thork files an injunction. The spoked wheel, Thork said, is still a wheel as he described in his original patent. It's still a disk that rolls on its side. So Thork says Doog cannot manufacture his spoked wheel without paying him, Thork, a license for the invention of the wheel in general.

But Doog argues his wheel is not a disk. A disk must be solid. But the examiner and the judges disagree. The spoked wheel is a disk. So Doog must either license Thork's original patent - or wait until Thork's patent expires.

Then suddenly along comes Dorg. He is a caveman science writer. He writes an article and points out that before Thork filed his patent some unknown caveman had carved a picture of a wheel on the side of a cave - but he didn't patent it. That is, the concept of the wheel had been previously disclosed and was public knowledge before Thork had filed his original patent. So the basic patent of the wheel - Thork's patent - is invalid. And because the concept of the wheel was already known from the prior art, no one can patent the basic wheel.

Since no one can patent the basic wheel, anyone can sell it. But not, we should say, a spoked wheel. The spokes and the spoked wheel is a substantial and novel improvement - that is they constitute a new invention. Therefore Doog's patent is still valid.

So Doog can now practice his new invention unencumbered by competition. As long as his patent has not expired, so no one else can market a spoked wheel or even use spokes.

So with the money from the spoked wheel business, Doog sets up a research and development department. His caveman scientists and engineers begin to find even more uses for the wheel - not just the spoked wheel but the basic wheel. They find they can put them on the sides of wooden box and you have a new means of transportation. You can put buckets along the side and put the wheel in a stream of water and it will turn an axle. The wheel can even be made out of rough stone and hooked to a wooden wheel in the water and you can automatically grind grain. All of these are new inventions even though they used the basic concept of the wheel.

At this point Doog files a pletora of patents. They prevent anyone from using his inventions, some he turns into commercial products, others he doesn't.

Of course, Doog becomes rich, and the world remembers him as the inventor of the wheel.

But then there's another caveman inventor. His name is Mork. Shortly before Doog had filed his patent for the spoked wheel, Mork had invented what he called the table. It is made by carving a bit of rock into a square and putting it on another rock. You can use the table to eat your mammoth steak on without setting them on the floor.

But before he filed his patent, Mork read about Thork's original wheel. Although the table is square, it looks sort of like a wheel. In fact, it's like a wheel that you can store on its side and it won't roll away.

So Mork writes in his patent that although the table is primarily to keep your mammoth steaks off the floor, it can also be used as a wheel that won't roll away. He tries to get the famous caveman financier. J. P. Nagrom, to give him some money to build a gigantic table that he says will roll all the way from Yellowstone Caldera to Olduvai Gorge. J. P. gives Mork enough to start building the gigantic wheel.

But soon some of J. P's caveman banker friends tell him that the square wheel is a bust. Then when Doog's spoked wheel begins to take off, J. P. decides to invest in Doog's business instead. Mork pleads for more money from J. P., but J. P. says he's not inclined to invest further.

Mork, though, now retires to his cave-hotel, and his in his old age - perhaps 35 years old - begins to give interviews to the Caveman Press. He points out that he originally had actually invented the wheel before Doog who had merely "perfected" his idea by making it round. Soon the word starts to spread how Mork was the real inventor of the wheel and Doog "stole" the idea from Mork.

I Think, Therefore I File

So we see that no individual invented the wheel. It was a process that took years - centuries actually - and required the contributions of many individuals. Also the patents that did issue were highly specific and were really improvements over the basic concept of what we call The Wheel.

But who did invent The Radio?

That, of course, depends on what you mean by The Radio. The general idea of somehow sending telegraph messages without wires was old. Someone probably thought of sending wireless messages as soon as there were telegraph wires.

Certainly by 1872, two Americans - Mahlon Loomis, a dentist from Washington, D. C., and William Ward, who specialized in making bomb fuses, flags, and hair gel - were issued separate patents which the courteous can interpret as being for the radio. Without going into details, William's patent is quite a laugh, and the less polite would call it pseudo-scientific claptrap.

Many people are also skeptical about Mahlon's claim that his device really worked. Others, though, think he may have had some kind of long range interaction between his kite-born antennas. Today, though, few people consider that either Mahlon or William really invented the radio.

Instead the first, deliberate, and intentional - and real - creation, broadcasting, and receiving of electromagnetic waves with frequencies of 3000 to 300,000,000,000 cycles per second - that is, radio waves - was by the German professor Heinrich Hertz in 1886. Heinrich, though, was simply trying to prove that electromagnetic waves - predicted by the Scottish professor, James Clerk Maxwell in 1864 - really existed. But Heinrich did not recognize the waves as a way to send messages. He was simply confirming a theory. Still, if the deliberate sending and receiving radio waves is "inventing radio", then Heinrich did it.

Things happened fast after Heinrich's demonstration. He may not have thought of using his set-up to send and receive messages. But others sure did.

You also read that William Preece, an engineer who had studied with Michael Faraday, took Heinrich's basic design and transmitted Morse Code. Exactly when seems a bit confused. A date of 1892 is often found but an report written in 1899 mentioned the experiment was "five years ago", ergo, 1894. So if deliberately and successfully sending and receiver a wireless code was "inventing the radio", then William did it.

And Nikola ....?

It was in the early 1890's, and after Nikola had already developed a name for himself, that he began giving talks on transmitting electric power without using wires. Some of these talks were well-publicized. The trouble is it's hard to say what he actually did and when because of his claims in later interviews.

For instance, as early as 1891 Nikola had conducted experiments that he later claimed his assistants recognized were "wonderful results" to "transmit energy without wire - telephone, telegraph, run cars [i. e., street cars], and lights at any distance." Some people think this meant he had indeed "invented" radio. The trouble he never made these claims until 1916, and he never invented any device which did what he said.

But we can be pretty sure what Nikola was talking about. In the course of his research, Nikola had invented an electrical device now called a Tesla coil. A Tesla coil generates high frequency and high voltage alternating current. And we mean high. You may have seen one at science museum demonstrations.

At various lectures in the early 1890's - such at Columbia University (then called Columbia College) and at Philadelphia's famed Franklin Institute (at one time mercifully briefly renamed as "The Franklin"), Nikola demonstrated that when he fired up his coil you could make a special type of electric bulb - called a gas-discharge tube - light up even though the bulb and coil were not attached. This is because the electric field causes excitation of the atoms of the gas and they emit light. His device, he pointed out, could be used to transmit electrical power from one place to another without sending it through wires. In fact, he had been granted a patent for this idea in 1891.

What actually Nikola accomplished is confusticated by what he said he did in later years. Some students of Nikola's life feel he was actually planning to demonstrate radio transmission for 50 miles but there was an accident and his lab burned down.

But the sad fact is that Nikola remained focused on what was really the wrong goal. He wanted to generate long range wireless electric power sufficient to run large electrical motors. As laudable as this goal was, for reasons we'll discuss later, it was something that was not - and never has been - achieved.

But Nikola kept trying and in 1897, Nikola filed for another patent "System of Transmission of Electrical Energy" This invention - as Nikola said - was primarily a means for transmitting power for industrial use. It issued three years later, 1900, as US 645,576, and was, as we saw, the patent the Supreme Court cited. But in all his life, Nikola and his invention never sent a single radio message, made a telephone call, ran a street car, or lit up a house.

So why did the Supreme Court cite the patent if it was about transmitting power for industrial uses and not sending radio messages?

When Is An Invention is Not an Invention?

But point of fact. US 645,576 does not patent radio communication. That's because although Nikola speculated that his device might be used for "transmitting messages at great distances", he did not make a claim that it did.

Like all patents, US 645,576 has a body where the invention is described. Then at the end there is a set of claims. It is the claims that legally constitute what you're actually patenting.

Now it is a sad fact of patent life that what ends up in the final claims is not always what the inventor put in the original application. The reasons vary, but most often the examiner has pointed out that the claims were too broad and were covered by some earlier patent. The inventors, though, need not give up. They might be able to narrow the claims down and hopefully get their patent.

But there's a dilemma. Narrow claims mean you're more likely to get your patent, yes. But someone might also find another use for your invention that you didn't claim and patent that new use.

Such new use patents are quite common. For instance, you could create an ointment and patent it for soothing irritated cow udders. But then someone else might take the same ointment and patent it as a way to treat human baldness. Believe it or not, this is a real example and not made up.

So what to do?

You do what Nikola did. You cover your rear end by disclosing as many ideas as possible - but in the body of the patent. There you can speculate to your heart's content. Anything you think your invention might be good for - even if you have no idea if your invention really does it - you can put it in the body.

Unless a disclosure is in a claim, it isn't part of the actual patented invention. But if the disclosure is in the body of the patent but not the claims, this might stop someone from filing a new use patent . You can also make a disclosure in an article, an interview, or even a lecture.

In his claims, Nikola mentioned nothing about transmitting messages.

But in the body?

Well, there he wrote:

While the description here given contemplates chiefly a method and system of energy transmission to a distance through the natural media for industrial purposes, the principles which I have herein disclosed and the apparatus which I have shown will obviously have many other valuable uses - as for instance, when it is desired to transmit intelligible messages great distances, or to illuminate upper strata of the air, or to produce designedly, any useful changes in the condition of the atmosphere, or in manufacture from the gases the same products as nitric acid, fertilizing compounds, or the like, by actions of such current impulses for all of which and for many other valuable purposes they are eminently suitable and I do not wish to limit myself in this respect.

In other words, Nikola is saying his invention might be used not just for wireless power, but for illuminating the atmosphere and creating useful chemicals like fertilizers. Then for good measure he throws in the catchall phrase - "for many other valuable purposes". That is, Nikola claimed you could use his patent for pretty near everything.

But notice the phrase, "... when it is desired to transmit intelligible messages great distances ..."?

So in the entire patent, these nine words were what Harlan cited to say Guglielmo's improvements had precedence and could not be patented.

And we repeat. The sentence is in the body of the patent but not in the claims. Nikola's patent is not for the invention of radio communication. And deliberate sending of messages by radio waves had already been achieved by 1889. So Nikola did not - quote - "invent the radio" - unquote - anymore than he invented making fertilizer.

More on the fertilizer bit later.

Why didn't he put it in the claim?

Simple. The examiner wouldn't have allowed it.

Patent examiners are supposed to act in good faith and allow claims that they feel have been demonstrated or that it is obvious that the invention would work. However, how Nikola's coil would transmit intelligible messages long distances was not clear and as we pointed out was completely speculative. Nikola could speculate all he wanted in the body of the patent, but the examiner would not allow such a claim. So Nikola's invention is not for radio - or any other means of transmitting messages.

Despite his long life, Nikola never sent any messages - intelligible or not - with any new invention. But there was someone who did.

Someone like Guglielmo Marconi.

(Reducing to) Practice Makes Perfect

And as far as saying Nikola invented the radio, there was just one wee little problem.

That's because July, 1896 is not after March 1897.

Nikola's patent was issued in 1900. But it was filed in March 1897. This, Nikola's friends point out, was way before Guglielmo made his first transatlantic broadcast in 1901.

But ... (you knew there would be a "but") ...

On June 2, 1896 - that's 1896 - Guglielmo filed British Patent 12,039. What makes this patent so important is it is highly specific as a means of both sending and receiving wireless signals. And the purpose was specifically stated in the claims. So this was indeed a patent for wireless communication. And we repeat - it was in 1896.

Now what surprises Americans is that British patents must be considered by US patent examiners when considering other patents. That is, if someone tried to file a US patent for the same or similar apparatus patented in Britain, the US patent examiner would point to the British patent and say, sorry, it's been done. Now as long as the British patent had no US equivalent, anyone could make and sell the device in America. But you couldn't patent it.

But as far as sending and receiving messages, Guglielmo had patented a working practical invention specifically for that purpose. And so he had established his precedence using his particular device.

And then in July - again 1896 - Guglielmo demonstrated his invention to the British Post Office. Then in September - yes, 1896 - he gave a demonstration on Salisbury plain.

That is, Guglielmo had both designed, patented, and built a working apparatus. Then he made an actual reduction to practice of useful wireless communication. This was before Nikola even filed his patent.

This, then, is why histories of radio cite Guglielmo as the inventor of The Radio by which we should mean practical long distance wireless telegraphy. And it's why in 1909, Guglielmo won the Nobel Prize. For all the people who generated radio waves, at some point someone has to put together a device that - as the commercials say - really, really works. That was Guglielmo.

The Wild - and We Mean Wild - West.

Now there is one invention that Nikola invented. And he really was ahead of his time.

In 1898 Nikola patented a radio remote control device for driving a boat. He even made a working model and gave a demonstration in New York. By today's standards the electronics were quite elementary, but with an actual reduction to practice, Nikola got his patent almost immediately. Filed in July, 1898, it issued five months later. That, ladies and gentlemen, is fast.

But Nikola couldn't get anyone interested. Although it's true in later years that Nikola was rather bitter about how he could never get people interested in his ideas, but at the time, he didn't push remote control. He was still working on transmission of wireless power.

We have to emphasize. Nikola had not been interested in making a wireless telegraph. He wanted to send electric power to run machines. But by 1898, Guglielmo was making big news by demonstrating a working wireless telegraph - and getting paid for it. So Nikola was getting worried. He soon began to think of including communication in his experiments. And he was thinking big

So Nikola decided to move to a place with plenty of room. And in 1899, what better place than Colorado Springs? He thought the high altitude would help his experiments. That was Nikola's theory and Nikola was a believer in using theory to guide the experimentalism.

One criticism that Nikola had of his old boss, Thomas Edison (whom he actually spoke highly of), was Tom knew no theory. So he just tried everything. That is, Edison's approach was, well, Edisonian. If Tom had only learned some theory, Nikola said, Tom could have saved a lot of time.

Big Tom

No Time for Theory

Of course, theory only helps if you are using a correct theory. Use the wrong theory and you're likely to fare worse than no theory at all.

In Nikola's time - here we're talking 1899 - electrical theory was rudimentary. Now we're not talking about the math of electricity - it was quite sophisticated and accurate. But no one really knew what was going on at the atomic level.

Today we know that current is electrons flowing in a wire, either in one direction (for direct current) or back and forth (in alternating current). But in the early days the physical understanding had not advanced much beyond Benjamin Franklin's theories of an "electric fluid" going through wires. But Ben thought that there was excess fluid - which he called positive - where really there were fewer electrons - which he called negative. This meant that even today you will read that the current flows in the direction opposite of which the electrons move.

But Nikola really had a surprisingly poor grasp of theory. While most scientists understood radio waves were transmitted through the air, he questioned whether radio waves existed. Instead, he believed it was the earth's "vibrations" that transmitted the power and the earth was a giant conductor. Or at least sometimes that's what it seems like he thought.

What was not a theory - it was a fact - was that Nikola needed money to carry out his plans. Now for most of his life Nikola was an independent researcher and consultant who today would get his money from government or large corporate contracts. The bad news was before World War II government funding was rare, and scientists mostly had to use their own money or to personally hit up on rich people for - to use Howard Hunt's term - the "ready".

But the good news was the 19th century was also the era of accessibility. You could literally walk into the offices of the Big Boys and if you waited you could talk to the most powerful men in the world. Once a teenager from Virginia City, Nevada, walked into the White House and asked to speak to the President. Ushered in to the great man's office, he asked if the President could wrangle him a spot at the Naval Academy. Eventually they found a spot, and the kid - Albert Michelson - later became the first American to win a Nobel Prize in Physics.

So early on Nikola became a master at schmoozing the Men with the Money. In New York, he attended functions with the high and mighty. He frequented the finest restaurants (Delmonico's was a favorite) and to make his contacts easier, he lived in fancy hotels in downtown Manhattan. Naturally this lifestyle wasn't cheap and Nikola, often living on credit, began to get into debt.

For his Colorado experiments, Nikola got one of his well-to-do friends, Leonard Curtis, to work a deal for a location and to obtain electricity from the local power plant. Then he got John Jacob Astor - the John Jacob Astor who was probably the richest man in the world and who later went down on the Titanic - to chip in $30,000 cash.

So in a tailor-made building - which had Dante's quote "Abandon Hope All Ye Who Enter Here" displayed over the door - Nikola set up what was the largest Tesla coil he had ever made. It was indeed impressive. It sent off huge electrical bolts that actually produced thunder.

By now Nikola was less charitable with Guglielmo (whom he had called "a good fellow") than he had been. He was irritated how the New York papers had gone crazy about the way Guglielmo's wireless telegraph was actually sending real messages. Huh! Here was that rich kid getting all the credit just because he had demonstrated something while he, Nikola, was working on something he knew would work.

To this day, no one can tell what the heck Nikola really did in Colorado. His notes - recorded as daily diaries confuse even the experts.

Part of the problem is it's hard to sort out when Nikola really did discover something new or when it is simply his musings of later years. For instance, he may have discovered that there is a resonance frequency of the earth even if his interpretation was not the modern concept of Schumann resonances. But then maybe he didn't.

He also evidently did light up electric bulbs - but only about 100 feet from his coil. That was scarcely an advancement over his lecture demonstrations given how much juice he was using. To be accurate - or from despair - modern authors sometimes speak of Nikola's "claimed" discoveries.

You will also read that at Colorado Nikola claimed he was receiving regularly spaced pulses that seemed to come from nowhere. His conclusion was he was received transmissions from aliens from outer space - Mars or Venus probably.

This, needless to say, is certainly not correct, and people have tried to figure out what Nikola was really receiving. One reasonable suggestion is he really had detected radio signals from outer space. So had he lived longer, he could have - and certainly would have - claimed it was he that invented the first radio telescope.

Once more it's impossible to sort out what Nikola actually did at the time from what he claimed in later interviews. Nikola's notes from Colorado Springs say nothing about receiving any beeps from outer space. So Nikola's detractors pooh-pooh the story entirely.

Sorting out what Nikola did is further complicated by his flair for the dramatic - and we must admit - his fondness for fabrication. The famous photo of him sitting in his Colorado laboratory while the massive electric lightning bolts flash around his head - believed by many to be a picture of an actual experiment - is really a phony double exposure. We know this because Nikola 'fessed up in his notes.

But there is one accomplishment we cannot doubt. In one of his experiments, he charged up his coil and blew out the entire power for the city of Colorado Springs. He returned to New York after nine months.

Back in the Big Apple

Nikola was getting more and more irritated with Guglielmo - who he said was using 17 of his patents. He didn't elaborate and to this day no one has found the patents he was talking about. The trouble, though, was Nikola had never really demonstrated that his device could do anything except make impressive flashes of light, light up a bulb from a few yards away, and blow out the power of a city.

So when Nikola returned from Colorado with essentially nothing to show for it, he found his rich friends were decidedly lukewarm despite his enthusiastic assurances he was on the verge of great things. Still, J. P. Morgan - who had more money than he knew what to do with - gave him enough to get started for his next step. But Nikola's friend, George Westinghouse, did not invest.

Fortified with J. P.'s money, Nikola began to build a huge Tesla coil on Long Island. Called Wardenclyffe Tower, it was intended to send power thousands of miles. If we believe what he said, he was going to send energy to Paris.

This was all well and good, but as of yet Nikola had not sent anything of any kind to anyone - not even a message by two Dixie cups and a string. On the other hand, Guglielmo had been sending wireless messages further and further. The Marconi Telegraph Company had also issued stock which had risen from $3 a share to $22. Nikola kept making promises. Guglielmo kept sending messages.

Then on December 12, 1901, Guglielmo sent a message across the Atlantic. Despite Nikola's pleas and enthusiasm, J. P. refused any more funds. Even Nikola's friends began to think Nikola really didn't know what he was doing.

With no money to continue, Nikola had to pack it in. The tower stood for another decade and a half until it was pulled down, and Nikola's patents - even those that he felt Guglielmo had been stealing - soon expired.

The First of All?

The trouble is at some point an inventor has to deliver a product, and by 1905, Nikola had run out of rich friends to fund ideas that never led anywhere.

From the time he worked with George Westinghouse, Nikola had loved to give interviews. To the reporters Nikola had one pervasive message. If someone invented something, he had done it first.

Near the end of World War I Nikola described - and we quote one web site - "one of the first descriptions of what we now call radar." He said you could reflect and received the radio waves - which he now believed in - back on a fluorescent screen. He also said you should be able to determine range and direction.

As we now expect, Nikola was far from first to describe this new invention. In fact, the first person to discover that radio waves were reflected from objects was none other than Heinrich Hertz back in the 1880's. So the principle of radar had been well known for decades. But probably the first real and intentional demonstration of radar was in 1904, when German Christian Hülsmeyer demonstrated ships could detect other ships with the reflected waves.

And Nikola?

Well, as Nikola continued to talk to the reporter about what he had done, you realize he is talking about using - yes - the Tesla coil and the experiments he had done in Colorado. And the detector he is talking about was nothing more than an X-ray fluoroscope - known since the 1890's - and was not a prototype for the modern radar screen. Nikola then goes off into discussions of using X-Rays - yes X-Rays - to detect submarines.

Once more despite what Nikola said, there's no evidence he carried out any experiments himself. We understand why no one was interested.

Nikola the Un-Skeptical Chymiste

In another interview, Nikola continued to talk about his contributions to humanity:

The Earth is bountiful, and where her bounty fails, nitrogen drawn from the air will refertilize her womb. I developed a process for this purpose in 1900. It was perfected fourteen years later under the stress of war by German chemists.

But from the year that Nikola gave - 1900 - he must be referring to the patent we just quoted. This is where he said his apparatus could be used:

...in manufacture from the gases the same products as nitric acid, fertilizing compounds, or the like ...

Now in 1900 Nikola also gave an interview where he indeed said that his transmitter - the gigantic Tesla coil - could also be used to combine nitrogen and oxygen to form nitric oxides. These in turn could be used to form other nitrogen compounds which would be used to improve soil quality and so help mankind.

We have to emphasize. Speculating about something is not inventing the process. Leonardo da Vinci thought about and even designed flying machines. But no one says he invented the airplane.

Creating nitric oxides by an electric discharge had been known since the early 1800's. In fact, when Nikola gave his interview chemists were already working on the problem which was finally commercialized. But Nikola had nothing to do with either initiating or developing the process.

However, we must note that when Nikola spoke about creating a process that was "perfected" in World War I, he really stepped over the boundaries of good taste - and reality. He could only be referring to the Haber Process which uses high pressure nitrogen and hydrogen with an iron catalyst to produce ammonia.

2N2 + 3H2 → 2NH3

The ammonia also serves as a starting material for other nitrogen compounds like urea and nitric acid. The Haber Process was indeed developed by the German Jewish Chemist Fritz Haber because of the interruption of international trade caused by World War I. Today virtually all ammonia is produced by Fritz's method.

Alas, the chemistry of the Haber Process is unrelated to any electric arcing method and is far more efficient and economical. In other words, far from Fritz "perfecting" Nikola's process, Fritz had made the technology Nikola was talking about completely obsolete.

How Did He Do It?

That is, we would like to know how did Nikola Tesla get people to believe he was the Man Who Created the Modern World, while people like Guglielmo Marconi and Thomas Edison were hacks, thieves, and frauds who stole his ideas?

We'd really like to know this.

I though you would as Captain Mephisto said to Sidney Brand. There are a few things we need to remember.

There is a trick used in mind-reading acts called cold reading. There you make broad statements that apply to almost anything but are worded in a way to make them seem specific and prescient . The audience - or at least those who don't know the trick - are impressed.

Then there is a related trick where you first make a huge number of predictions. Naturally, some will be at least sort-of right simply by chance. But in the future, the news reporters and media will write about those few predictions and ignore the majority that were wrong. Mathematician John Paulos dubbed this phenomenon the Jean Dixon Effect although it was actually alluded to in one of the old Adventures of Superman episodes, broadcast in 1953. It also helps if the reporters don't look too closely at the actual predictions, but simply summarize - or distort - them to make the prediction fit with what actually happened.

Next, if you predict that some new technology will be used in the future, pick a technology that already exists and is the subject of intense research but is not yet commercial. In the future, people will then think you were actually predicting something new. Jules Verne did this in his incredibly poor and unintentionally humorous novel, Paris in the Twentieth Century.

Finally, remember that historians are really writing about their own times rather than the times of the subject. If someone had beaten you to the punch, just wait until a time when people are suspicious of authority, love stories about conspiracies, and admire the underdog who lose out to the people who actually succeed.

Nikola took advantage of all these methods. For instance read what he said in an interview in 1915:

Very soon it will be possible for us to see each other at distances of thousands of miles; we shall be enabled to hear an opera, sermon, or scientific lecture, and be visually present in all kinds of meetings and transactions wherever they may be taking place and without regard to where we ourselves happen to be at the time

This will be come a daily business experience, not only to transmit with unerring precision a signature to an important document, but enable the recipient in a distant country to see it affixed by the sender.

Now this is indeed a pretty good prediction and can certainly be interpreted as seeing the modern cyber-paperless world with real-time life internet transmissions and video conferencing that began forming in the late 20th and early 21st century. But if we pause to review the state of research at the time, we'll see that Nikola was not inventing these ideas any more than Arthur C. Clarke invented the Internet in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

By 1915 - when Nikola gave the interview - voice transmission had been achieved and in fact was old hat. As early as 1910 a broadcast of some opera singers was made from the Metropolitan Opera House. One singer was, of course, Enrico Caruso.

And more of a surprise. Prototype systems of transmitting images wirelessly had also been demonstrated. Research was even underway to transmit moving pictures as well. Nikola knew about the ideas and was simply speculating that they would be commercialized one day. But it was other inventors, many of them unknown to the general public, who were actually making them work.

Of course, if you wish you can play the game in reverse and make Nikola look like a dunderhead. For instance consider his statements about what was then the upcoming millennium.

Today the most civilized countries of the world spend a maximum of their income on war and a minimum on education. The twenty-first century will reverse this order.

Long before the [21st] century dawns, systematic reforestation and the scientific management of natural resources will have made an end of all devastating droughts, forest fires, and floods.

Once a power plant [based on Nikola's coil] is in operation it will be possible to operate flying machines in any part of the world without fuel and light isolated homes in an ideally simple and economic manner.

I am convinced that within a century coffee, tea, and tobacco will be no longer in vogue.

Not that Nikola was always wrong, mind you. After the last quote he added:

Alcohol, however, will still be used. It is not a stimulant but a veritable elixir of life.

So to summarize, just do the following:

| 1. | Read interviews Nikola gave to reporters. |

| 2. | Pick out what seems to have come true and ignore what didn't. |

| 3. | Ignore the fact that the basic science and engineering of Nikola's predictions were already known. |

And hey, presto!, you've got Nikola the Man Who Invented The Modern World.

The Last Years

As he aged, Nikola grew increasingly bitter because, as he said it, no one was interested in his patents until after they expired. We do wonder, though, what Nikola had to complain about.

After all, for years he was able to get financial backing from some of the most powerful men in the world, work in his own labs, and take high paid consulting work. A great job if you can get it.

But now back in Manhattan, Nikola was going off the deep end. He began to hate earrings on women, developed ever eccentric behavior, and finally became fixated on the neighborhood pigeons. But he continued to live in good hotels, eat in the finest restaurants, and when he fell so far in debt that he could never make it up, George Westinghouse began paying his bills. A good job indeed.

And he kept giving interviews. There was, after all, nothing else to do. In 1941 and at age 84, in what was possibly his last interview, Nikola spoke to a reporter from the New York Times about a death ray he had invented. And yes, some people really believe it to this day.

You can rest assured we haven't heard the last about Nikola the Man who Discovered Everything. Recently we learned that Nikola had predicted the discovery of faster than light neutrinos that were reported by a scientist at CERN.

Indeed, Nikola did say that there were faster-than-light particles, certainly a good way to irritate Albert Einstein whose theories Nikola didn't believe. Unfortunately - for Nikola and the scientist - it later turned out that the report from CERN was due to a faulty electrical connection and a bad timer.

Still, there's one statement where it remains to be seen if Nikola was right on or not. In 1915, he told a reporter:

"When world wireless telephony, the transport of bodies and materials, and the transmission of energy for all industrial and commercial purposes become facts, the earth will have shrunken in size so as to put nations in close touch and make international complications and wars an impossibility!"

Yes, the transport of bodies and materials.

So when we see the Star Trek Transporter on the market, remember. Nikola got there first.

References

Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age, Bernard Carlson, Princeton University Press, 2015. Although the title is a bit enthusiastic, the book is balanced with good discussions.

Tesla: Man Out of Time, Margaret Cheney, Prentice-Hall, 1981. Pretty pro-Nikola.

The Science of Radio, Paul J. Nahin, American Institute of Physics, 1995. Has a brief, but harsh assessment about Nikola.

Signor Marconi's Magic Box, Gavin, Weightman, Da Capo Press, 2003.

Marconi: Father of Wireless, Grandfather of Radio, Great-Grandfather of the Cell Phone, the Story of the Race to Control Long-Distance Wireless, Booksurge Publishing, 2010. Obviously about Guglielmo.

"The Rise and Fall of Nikola Tesla and his Tower", Gilbert King, Smithsonian Magazine, February 4, 2013. A good article about what Nikola was really trying to do and why ultimately he ended up losing his backers.

"Nikola Tesla's Amazing Predictions for the 21st Century", Matt Novak, Smithsonian Magazine, April 19, 2013.

"Nikola Tesla the Eugenicist", Matt Novak, Smithsonian Magazine, November 16, 2012.

A Machine To End War", Nikola Tesla, Liberty Magazine, February 9, 1935, pp. 5 - 7.

Nikola Tesla on His Work With Alternating Currents and Their Application to Wireless Telegraphy, Telephony, and Transmission of Power: An Extended Interview, Twenty First Century Books, 2002

"Nikola Tesla Predicted Faster-Than-Light Particles in 1932", http://www.gizmodo.com.au/2011/09/nikola-tesla-predicted-faster-than-light-particles-in-1932/

"Did Tesla really predict neutrinos faster than light?", http://denversecrets.com/secret-debunked/tesla-predicted-neutrinos/

Marconi Wireless Tel. Co. v. United States 320 U.S. 1 (1943).

Encyclopedia of Radio 3-Volume Set, Christopher Sterling (Editor), Routledge, 2003. Comprehensive but expensive.

Early Radio History, http://earlyradiohistory.us/. Gives a lengthy explanation of the famous court case that ended up in 1943. Not a pro-Nikola opinion.

"What Are Improvement Patents and New Use Patents?", http://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/improvement-patents-new-use-patents-30250.html. A good short article about how improvement and new uses are real patents.

"Neutrino researchers admit Einstein was right", Alok Jha, The Guardian, June 8, 2012.

"Neutrino 'faster than light' scientist resigns", BBC News, March 30, 2012, http://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-17560379

"Tesla Polyphase Induction Motors", All About Circuits, http://www.allaboutcircuits.com/textbook/alternating-current/chpt-13/tesla-polyphase-induction-motors/

Twenty First Century Books, http://www.tfcbooks.com/default.htm. Good primary sources about Nikola.

"We'll Telephone to Stars!" Declares Scientist Nikola Tesla", Harry Burton, The Day Book, Vol. 5, No. 14, Octoer 13, 1915. An interview with Nikola.

"Tesla's Views on Electricity and the War", Winfield Secor, The Electrical Experimenter, August, 1917. Another Nikola interview.

Edison Technical System, http://www.edisontechcenter.org/.

"Mystery in Wax", Adventures of Superman, Cast: George Reeves, Phyllis Coates, Jack Larson, Neil Hamilton; Guest Star: Mira McKinney. Director: Lee Sholem; Writer: Ben Freeman; Broadcast Date: January 2, 1953. Amazingly - given today's pandering of television and motion pictures to an increasingly credulous and superstitious public - the old Adventures of Superman was pretty harsh on superstitions. In this episode Perry White gives a good summary of what is now called the Jeanne Dixon Effect, and in another episode Clark Kent pointedly reminds Jimmy Olsen that ghosts don't exist.

.