Pancho Villa

¿Revolcionario o Terrorista?

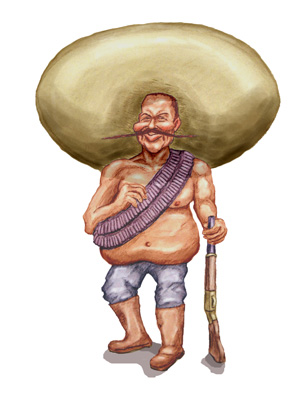

Pancho Villa

(Sin Camisa

Francisco "Pancho" Villa first came into the historical record on November 1, 1899 when he was 21. A police report in Chihauhua, Mexico noted that Pancho - under his real name of Doroteo Arango Arámbula - was arrested for stealing a couple of cows. The local judge released the kid for lack of evidence and young Doroteo's name continued to crop up until he was arrested shortly afterwards for assault. He was sentenced to the army and deserted a year later.

Nothing written about Pancho before 1912 - when he was listed as "Lieutenant Francisco Villa" commanding 28 men in the revolutionary forces - indicates he was ever anything more than a small time bandit who was hardly worth troubling about. His main activity was rustling livestock and selling it to local businessmen. Anything about Pancho's earlier life was written long after the fact, either by Pancho's enemies to make him look like a butchering sadistic killer or by himself and his friends to let everyone know he was really a latter day Robin Hood who spent his time robbing from los ricos and giving to los pobres.

Whether he was un gran general muy inteligente y valiente or un terrorista sádico y brutal, Pancho will be forever tied to the Mexican Revolution. A perplexing story for most gringos, the story of the Revolution only makes sense if you look on it as it was: a ten year period of anarchy where local states and regions were under the control of various armies, at least some of which did indeed start out as gangs of rustlers and grew or shrank in size as circumstances unfolded.

In general (no pun intended), the Mexican Revolution was fought for land reforms with the ultimate goal of having the owners of the large haciendas restore the land they had usurped from the small private farmers. Like we said, that was the general goal. Specifically the revolution was to oust dictator Porfirio Diaz and restore Mexico to a government where the officials (including the President) followed the constitution.

For ten years, an unlikely collection of poor, middle class, and well-to-do hombres raised armies and finally overthrew Porfirio. Naturally one of those leaders was Pancho who, as we said, started off as rustler and thief in Chihuahua. By 1912 - hey, presto! - Pancho was suddenly a revolucionario fighting for tierra y libertad, admired and respected. In fact, being an outlaw had given him unique qualifications to be a revolutionary leader.

How so? Well, in 1910 a young, well-to-do, and somewhat strange young man named Francisco Madero decided to run for president against Porfirio. Now Porfirio with a single brief (and actually bogus) hiatus had been in office for decades despite the constitutional ban on successive presidential terms. Francisco said Porfirio should not be allowed to serve any longer and so offered himself as an alternative who would also bring on the needed land reforms. Of course, Porfirio did good, like a dictator should, and threw Francisco in jail. But to show everyone he was a man who believed in the rule of law, he let Francico's dad - who was rich and influential - post bail. The proviso was Francisco remain on the family ranch and under constant guard.

Francisco was allowed to take exercise by riding around the ranch. One day when the mounted guards seemed particularly inattentive, Francisco simply spurred his horse forward and rode off into the sunset. He made it to the United States where he declared himself Presidente and called for open revolt against Porfirio.

Well, that's what made Pancho into a respectable citizen. Once the call for revolution was made, Pancho could still rob the rancheros and swipe and sell the cattle. And he still could barge into the casas grandes on the estates, take the money, antiques, and valubles. But now all the loot wasn't just plunder. It was capital to help Pancho expand his army and purchase supplies and more arms to fight for land and liberty. Of course anything left over went to the local entertainment industry - cantinas and aduanas - and Pancho himself had a noted fondness for women and song (we have to leave out the wine, as Pancho neither drank nor smoked). So in his own way, Pancho really was robbing the rich to give to the poor. Sure, the poor gave him something in return - particularly the pretty senoritas - but it was all in the name of the revolution.

But more importantly as a revolucionario Pancho could expand his markets so to speak. He could now legitimately attack government or city facilities - banks, police stations, and such things - and take all the ammunition and money that was around. As his control of the region grew, Pancho soon became the de facto governor of Chihuahua. He even began to print his own money (which was accepted by El Paso banks) and buy guns and ammunition from the United States.

By 1914, Pancho wore the hat of the commanding general of what was now a true army, El División del Norte. His forces were organized into cavalry, infantry, and artillery and was staffed along a military chain of command with officers and subordinates. At it's pinnacle the active army totaled about 10,000 men and women.

Yes, women. A remarkable feature of the Mexican armies - all of them - was they had a large contingent of women. These were the famous soldaderas, and although few of them actually fought alongside the men, some did. These ladies were by no means just the ubiquitous "camp followers" (wink, wink). A goodly portion were the legal and legitimate wives of the soldiers, often with kids in tow. Many provided support like preparing food, mending uniforms,and caring for the wounded. And as we say some of the ladies did indeed fight alongside the men, although this was not encouraged by the officers.

Pancho's soldiers idolized him and like many soldiers who idolized the leaders, they ribbed him a bit. Pancho's marching song was the folk ditty "La Cucaracha" which in addition to the usual traditional verses, the villistas added another.

Una cosa me da risa.

Pancho Villa sin camisa.

Ya se van las carranzistas

Porque vienen las villistas!

One thing sure to cause great mirth

Is Pancho Villa with no shirt.

Carranza's troops must now give way

Since Villa's men are on the way!

Pancho's military and political success brought him fame and even friends in the United Sates. There were quite a few Americans who joined his ranks, and American journalists and film makers of the infant industry also flocked across the border (Pancho cut a deal of 20% with the pioneer film maker D. W. Griffith). Even more surprising considering what came later, he was well regarded in official US military circles. General John "Black Jack" Pershing and Army Chief of Staff Hugh Scott had a high opinion of Pancho's military strategy and even invited him to Fort Bliss for a photo-op.

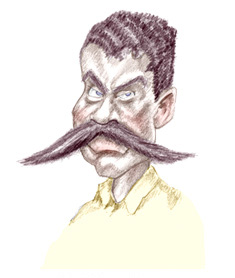

Emiliano Zapata

In One of His More Cheerful Moods

Now none of this meant that Pancho was a sweetheart. He was impulsive and quick on the draw, and his personality was marked by what can be courteously called mood swings where he would go from calm affability to maniacal spittle flinging rage in a minute. If he thought there was a reason (and it didn't take much to persuade him), he would execute anyone. Trials were a nuisance, but at least the method was usually the relatively humane (for the time) firing squad. But no one should think that Pancho was substantially different from the other leaders of the armies, whatever side. It was, to put it mildy, a most unpleasant time.

Porfirio was overthrown in short order and after 1911, the revolution should have ended. But for the next nine years - from 1911 to 1920 - Mexico had a decade of anarchy and violence. Mexico averaged a new president every two years starting with Francisco Madero and running through Victoriano Huerta to Venustiano Carranza and finally ending with Alvaro Obregon. All had been allies against Porfirio, but the friends soon found all sorts of irritating qualities in each other. All but Alvaro died in office (and when we mean they died in office, they died in office), and the only reason Alvaro didn't follow the mold was he was assasinated while running for a nonconsecutive second term. Despite common opinion, during the Revolution neither of the two most famous fighters - Pancho or the gloomy-eyed Emiliano Zapata - aspired for the presidency.

Although the revolution dragged on to 1920 and arguably later, by 1914 a lot of people in Mexico and elsewhere were sick of the fighting. America had considerable business entities in Northern Mexico (particularly the mining companies), and President Woodrow Wilson decided that someone had to be in charge if things could ever return to normal. So he recognized Carranza as president, but neither Pancho or Emiliano laid down their arms.

The merits of continuing the fighting was easy enough to rationalize since none of Mexico's revolutionary Presidents had done really anything to institute the promised land reforms. The only changes that were taking place were in the states held by the revolutionaries that kept fighting. Any changes, though, were less ideological than practical since to fund the revolution, the easiest way to raise money was to commandeer the land, money, livestock, and crops from the haciendas or if you were a nice revolutionary you accepted "loans" from the current hacendada. But as far as Mexico's official government (and the United States) was concerned, Pancho was once more just a dos centavo bandito. Worse (for Pancho) one of his major sources of ammunition - buying from US markets - had dried up.

Pancho's response to Wilson's recognition of Carranza's government was fitting with his character - quick, intuitive, brutal, and without much thought for the long term. On January 11, 1916, Pancho and his men stopped a train near Santa Isabel about 20 miles southwest of Chihuahua City. There were 17 American mining engineers on board. One got off to see what was going on and then heard shots. He looked down the train and saw Pancho had gathered the other Americans outside and had begun shooting them down. The lone engineer was able to get away but all the rest died.

Americans were shocked! shocked! at the murders. To show their outrage at such lawlessness and brutality and to demand an assertion of the rule of law, some citizens in El Paso siezed 12 of the local Hispanic residents, doused them with kerosene, and burned them alive.

Woodrow Wilson

He figured someone had to be in charge.

But Pancho wasn't done yet. On the night of March 9, 1916, he and about 600 of his men crossed the border into the United States. There was an army base three miles north of the border, Camp Furlong, just south of Columbus, New Mexico. There was an arsenal and Pancho and his men decided they could take what they wanted.

Unfortunately, Pancho had miscalculated, and militarily the raid was a disaster. The army base was guarded by 600 soldiers, not the 50 he thought was there. Pancho had to beat a hasty and empty handed retreat, and he ended up with more than 100 men killed. During the brief occupation of Columbus, Pancho had managed to burn the town and kill eighteen Americans, ten of them civilians. Another short foray into Texas was ineffectual and did little damage.

After the Columbus raid, President Wilson knew he had to do something about Pancho. He told Carranza he was going to send troops into Mexico. Carranza, knowing he couldn't do anything about it, acquiesced. General Pershing, who earlier had his photo taken smiling broadly with Pancho, crossed the border south and was helped by a young tenor voiced lieutenant named George Smith Patton, Jr. The force - called the American Punitive Expedition - was equipped with all the new state-of-the-art military equipment including machine guns, automobiles, trucks, and the new fangled (and decidedly ineffective) airplane.

Black Jack and the Americans spent the next ten months looking for Pancho, with both the motorized vehicles and mounted cavalry (and this was the last real use of American mounted troops in combat). Except for capturing and killing some of Pancho's officers, they came back empty handed. The planes went aloft and flew over the countryside but found no Pancho. Response of the local citizens was a mixture of indifference, hostility, and disinformation (Pancho, Pershing wrote, was everywhere and nowhere). Mexican resentment of the Americans rose, and Carranza canceled cooperation of the Mexican railroads and demanded Wilson pull his forces out of the country. Woodrow refused. American forces occupied Veracruz, and the United States and Mexico came close to war. The few real battles the Americans fought were not with Pancho, but with some of Carranza's units.

The American forays into the countryside had to be limited due to supply line problems. With no real fighting to do, most of the American soldiers spent their times in the camp and the Mexican pueblos, drinking, and trying to get along with the pretty senoritas. Ironically many of the Mexican men rubbing elbows with the Americans at the cantinas were Pancho's own soldiers who simply doffed their bandlieros and came into town for some fun. Pancho's buddies even attended the new entertainment, the cinema, sitting alongside of the soldiers.

All the time the Germans were watching the situation very carefully. This was 1916, after all, and the Germans were busy fighting England and France in the War to End All Wars. This was the first war to effectively employ the modern techniques we all know and love, including underwater attacks with submarines.

At first, the German U-boats had targeted all ships, both military and civilian, on the theory that the civilian vessels were carrying war supplies. However, the Germans had sharply curtailed U-boat attacks after the outcry from the sinking of the British liner, the RMS Lusitania.The nearly 1200 deaths included 128 Americans. But the United States was still sending supplies and goods to Germany's enemies, and some officers in the German command wanted to restart unrestricted targeting of civilian merchant and liner ships even if they flew a neutral flag. Other German leaders, though, balked at risking having the Americans joining the fight with Britain and France.

But the bungled invasion of Mexico tipped the edge. Documents from Germany show conclusively that the American's failure to capture a two-bit bandito like Pancho convinced the German military that the Americans were an absolutely ineffective fighting force. Almost as soon as Pershing withdrew from Mexico in January 1917, Germans resumed its attacks against American ships and four were sunk.

Now - quote - "knowing" - unquote - they could whip the Americans, the Germans sent a telegram to Carranza saying if Mexico pitched in with the Germans, they could have all the American Southwest back. The telegram was intercepted by the British who in turn showed it to the Americans. America declared war on Germany in April, and the American Expeditionary Force - led, by the way, by General "Black Jack" Pershing - was sent "over there". When the War ended, America was the big winner and arose as a major world power in the new century.

And what about Pancho? He pretty much went downhill after the Columbus raid. Without international support - which meant no money to pay his troops - his army dwindled in size. He found he spent most of his time retreating and became more impulsive than ever. He started shooting anyone. If he hired a guide to lead him through some unfamiliar terrain, he'd shoot him so he couldn't tell anyone that Pancho had been through. If he came across a group of workers in a field, he'd shoot them so they couldn't tell the carranzistas that they had seen Pancho. Of couse, this brutality turned the local inhabitants - at one time Pancho's strongest supporters - against him. Soon he and perhaps 50 men were once more holed up in the Chihuahua hills.

Pancho's Waterloo came when he decided to attack Ciudad Juarez. A garrison of federales was stationed there, and Pancho reasoned if he could drive them out it would give him a direct line to the US border and better access to black market supplies. Unfortunately, some of the bullets from the battle whizzed across the border into El Paso where the cities residents had climbed to rooftops to watch the fight. Several citizens were wounded, and the Americans once more sent troops into Mexico. Pancho withdrew, discomfited.

Then in 1919 Carranza was assassinated (the usual method to insure transfer of power during the revolution), and Alvara Obregon became president. After some negotiations, he offered Pancho amnesty, and Pancho, seeing that continuing the fight was futile, accepted. He retired to a sprawling hacienda - over 160,000 acres - outside of Parral. The irony of Pancho's transition from a revolutionary to a hacendado was lost on no one.

The Mexican revolution was complex and convoluted and bloody and fought without quarter. Politically correct or not, the pictures from the stereotypical Latin American revolution - so often parodied in film and television shows from the Three Stooges to the Monkees - have an element of truth. The men - and their women soldaderas - did festoon themselves with the bandoleers and the soldiers often decked themselves out in the baggy peasant pants and the wide sombreros. Prisoners were dealt with mostly by firing squad, and there were times of true political terror throughout the country. Estimates of the deaths in the Mexican Revolution generally are about a million.

Las Soldaderas

Pancho was a man of contradictions. He really would ride foremost into battle with bullets blazing around him, but when he was once captured and readied for execution, he fell to his knees and blubbered like a baby. He claimed he was fighting for the poor peasants and villagers, but after the war set himself up as a hacendado complete with peasants. He fought for land reforms, but hated communism and personally was politically conservative and a capitalist.

Without formal education himself, Pancho admired and was even awestruck by intellectuals. A man who would shoot down another on impulse, he was genuinely fond of children and set up a school on his hacienda. Chauvinistic toward women at best, he was a surprisingly kind father to his own children - at least the kids he could keep track of. The number of times he was married varies with the source - the low end estimate is four - the high end around 26 or 27 (but who's counting?). All the numbers are probably correct since most of his - quote - "marriages" - unquote - were formalities. If he saw a lovely senorita he fancied he would propose. If she accepted (and they usually did), the proper papers would be drawn up and duly signed. After his honeymoon, Pancho then made sure the certificate would disappear in time for his next nupcias.

By 1923 Pancho was a settled and wealthy landowner living outside Parral. There were a number of Americans living in the town, and Pancho would have his picture taken holding their kids. But Pancho still had enemies, plenty of them, and was decidedly nervous and cautious when dealing with visitors.

On July 20, Pancho went to a neighboring town to attend the christening of some friends' newborn baby. He seemed to be more relaxed than before since he was accompanied only by two body guards and his chauffeur. His normal contingent of protectors had usually been about fifty.

On the way home, Pancho himself took the wheel of his Dodge sedan. As he was driving through Parral, he heard the familiar shout, "¡Viva Villa!". Whether he smiled and waved in acknowledgement no one knows. But those were the last words he ever heard. A group of men opened fire from a nearby building and literally riddled the car with bullets. Pancho was hit nine times, once in the heart. He was dead before the car rolled to a stop. So anything you may read about Pancho's dramatic last words spoken to newspaper reporters are bogus.

No one knows who was behind Pancho's assassination. Pancho had made some rumblings about running for President, and so some historians point to President Obregon, who if not actively planning the murder, they think was in the know. That it was a well organized plot seems clear since among other things, the entire Parral police force was called out of town and was absent when Pancho drove through.

Pancho's reputation has shifted in time and place. Even in Mexico in the early 20th century, the middle and upper economic classes saw Pancho as an embarrassment to their country. His depredations created the stereotype of the mustachioed, sombrero-wearing, bandoliered bandito which even today is a continuous source of irritation to the Spanish American community (and which ultimately resulted in the demise of the Frito Bandito). On the other hand, the economically lower classes always admired him. He at least gave the gringos a run for their dinero. Spanish language ballads of his exploits - the corridos - are still popular and actually have quite catchy tunes.

Still for most Norteamericanos, Pancho remains the sadistic, maniacal murderer who would handle all his problems by putting his enemies against an adobe wall and blasting them away. But with the Hispanic population growing in the United States - and if the signs of the time are indeed signs of the time with los Estados Unidos eventually becoming a bilingual nation (a perfectly common and natural state of affairs in many countries, but held in horror by the more xenophobic gringos) - the reputation of Pancho Villa may actually get a shot in the arm.

In fact, it might already have done so. In Columbus, New Mexico, there is a recreational area on the site of the old Fort Furlong. Some of the original buildings are still there and listed in the National Register of Historical Landmarks. To get there you drive South from Deming on Highway 11. Pass through the town and turn right on Highway 9. Look on your left for the sign.

Pancho Villa State Park.

¡Viva Villa, amigos!

References

The Life and Times of Pancho Villa, Friedrich Katz, Standford University Press (1998). Nearly a thousand pages of Pancho Villa may be a bit much for the average reader, but this was and remains the definitive biography. Frederick was able to read the actual manuscript of Pancho's autobiography - now in the hands of the descendants of Pancho's amanuensis - and so found that the stories you hear about Pancho are not necessarily what Pancho himself wrote. For instance, he did not claim he killed a hacienda owner who outraged his sister. He said he came home and found the man and others trying to abduct her. So Pancho got a gun and shot the man in the foot.

There is an awful lot of background in this book, and it is needed for those who want to see Pancho in context of his country and era. But it sometimes is hard to find Pancho for the trees. In any case, the irony of Pancho starting out as a peasant living on a hacienda, then - quote - "forced" - unquote - into outlawry before moving on to be el gran liberator until he finally winds up as a hacendada with peasants of his own hardly needs comment.

Villa and Zapata: A History of the Mexican Revolution, Frank McLynn, Carroll and Graf (2001). A good book for learning about the Mexican Revolution. Frank starts his book with the birthday celebration of Porfirio Diaz, filling in the details of how this most quintessential of quintessential Latin American dictators came to and held on to his power. The book then moves on to the rise and fall of Madero, Zapata, and Pancho. A bit more compact telling than Pancho's biography.

The Face of Pancho Villa: A History in Photographs, Friedrich Katz, Cinco Puntos Press, 2007. A later book for the generral public.

"Pancho Villa Assassin's Kin Say U.S. Government Still Owes Reward", Alfredo Corchado, Dallas Morning News, March 9, 2008, So even today we still have Pancho! Interesting to note that the name of Pancho Villa State Park in Columbus, New Mexico is not a name that has total local approbation.