Sir Robert Robinson and Sir Christopher Ingold

Who Did What and When Did They Do It?

Sir Robert Robinson and Sir Christopher Ingold

Sir Robert Robinson, Waynflete Professor at Oxford from 1930 to 1955, was by no means a wimpish one dimensional do-nothing-but-chemistry nerd. He was an expert chess player (becoming the president of the British Federation of Chess from 1950 to 1953) and a skilled pianist. He was even an Alpine mountaineer and on one of his Swiss sojourns he met Edward Whymper the English artist and illustrator who had first scaled the Matterhorn. Sir Robert himself did not shy away from difficult peaks and at age 17 made a grand traverse of the Wetterhorn.

Noted as a "good worker but messy", Sir Robert studied chemistry at the University of Manchester and graduated in 1906. Now you will read at some places on the Fount of All Knowledge that he got a doctorate in 1910. Now this is true but he did not get a Ph. D. In England at that time a Ph. D was not a particularly popular degree mainly because there wasn't much point to it.

Now in the late 19th and early 20th century in a country like Germany with its highly regulated academic industry, a college degree and fünf pfennigs might get you eine Tasse Kaffe. But in England (and America) even full professors often had only a bachelor's. Higher degrees were often honorary and awarded when the schools they taught at thought they were worth it. For instance, J. R. R. Tolkein's "graduate" Oxford degrees, the Master of Arts and Doctor of Letters, were both honorary, the last awarded when he was 80.

For scientists, though, there was sometimes the option of getting a D. Sc., a Doctor of Science degree. This was not an honorary degree but was earned based on your research papers. After Robert - not yet "Sir" - graduated he was invited by William Henry Perkin (no, not the W. H. Perkin who discovered aniline "mauve" dye, but his son) to work in his lab. So by 1910, Robert had accumulated enough publications that Manchester awarded him a D. Sc.

But whatever the degree, college teachers usually started out as something like an instructor or reader (assistant professor in America). In England the title professor was reserved for what in the United States is more like a department chairman. It usually took years to wind your way to the professorial pinnacle.

Robert, though, hit his professorships pretty quickly. He was offered a chair that had just been created at the University of Sydney in 1912. He was only 26 - very young for an actual professor. Now Sir Robert always denied he was motivated by ambition, but instead saw the job as a place where he could climb the New Zealand alps (he was in the party that made the first ascent of Mount Meeson). But on the other hand, once you became a professor in the English University system,you had a leg up for landing the title at other schools.

Sir Robert's publishing was quite prolific even by today's hyperinflated standards. But his research at Sydney hit a snag when he had a fire in his lab which wiped out most of his chemicals. What caused it, we're not sure, but experimental - ah - "techniques" - of the early 20th century were not up to today's safety standards. In fact, Sir Robert's preferred way of evaporating ether - which you always evaporate using only warm water - was to put his reaction mixtures in wide mouth quart jars and setting the fumes on fire - a method that even his students called "alarming".

So it's not too big a surprise that after two years in Australia Sir Robert accepted the chair at Liverpool. This was followed by a succession of professorships at St. Andrews, his old alma mater Manchester, then London, and finally he achieved the professorial epitome by landing his chair at Oxford. But you do wonder. If Sir Robert was as good as they say, why the heck he couldn't hold a steady job?

In any case, by the time he reached Oxford, Sir Robert was one of the best known of the world's organic chemists - that is, chemists who specialized in carbon compounds. His forte was isolating, preparing, and running reactions on natural products. He particularly liked working with compounds from the Brazilwood tree. Brazilwood (great for making violin bows) contains a number of compounds which have enough complexity to make them interesting, but also enough simplicity for chemists working in the pre-instrumental days to analyze. Besides, Sir Robert said, the compounds were so colorful that just working with them was its own reward.

It was during the course of his work on natural products that Robert had become interested in chemical theory. To say that at the time theory was primitive is like saying Huck Finn's raft was not quite seaworthy. It was only in 1916 (when Robert was 29) that Gilbert Lewis published his paper on the covalent bond and the "electron-dot" pictures with atoms sharing electrons. For years, the theory remained remarkably - some would say "refreshingly" - void of mathematics. Instead you could get by with drawing the chemical structures on paper - letters for the atoms and dots or lines for the chemical bonds - and while you peppered the atoms with plusses and minuses, you pushed electrons around while trying to figure what reactions made the most sense.

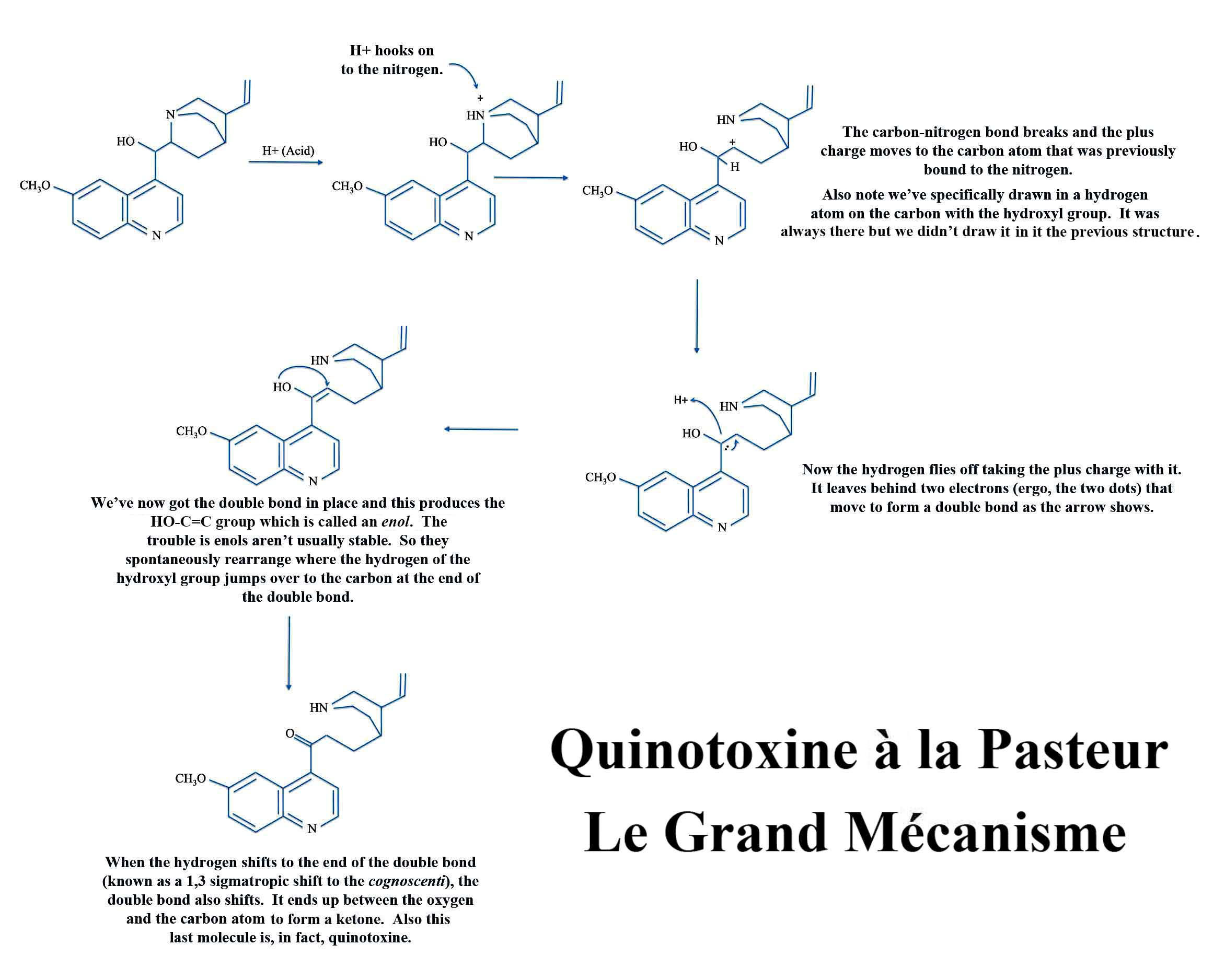

Sir Robert did not see theory as simple abstractions but as useful tools to systematize basic principles as a practical aid the chemist. In his papers on the reactions of natural products he would include his ideas of how one molecule changed into another. He was the first chemist to use the famous curly arrows to do the electron pushing which you'll get a good dose of if you take organic chemistry. To see a fairly simple example of electron pushing in a new window - of a reaction first discovered by none other than chemist Louis Pasteur - click on the image to the left.

Pushing Electrons with Louis

(Click on the image to open a larger picture in a new window).

Sir Robert continued to develop his ideas and he gave two lectures specifically about organic chemistry theory which included his special notation and terminology. These were published as a pamphlet in 1932.

Then why was it that by the mid-1930's if you stopped Joe or Josephine Blow on the street and asked who was the - quote - "inventor" - unquote - of the theory of organic chemistry, you would have been told it was Sir Christopher Ingold? Well, that's, if not a long story, then an interesting one.

Sir Christopher had graduated from University College London and taught at Leeds before returning to UCL where he remained until he retired. He wasn't a natural product or synthetic chemist like Sir Robert but preferred studying reaction mechanisms - that is finding out the detailed pathways that the molecules take from reactants to products and why some molecules react one way while similar ones do something else. By 1934 he had written a paper titled "Principles of an Electronic Theory of Organic Reactions" for Chemical Reviews. This review marked the beginning of the modern era of physical organic chemistry, and if you've taken an organic chemistry course and been hammered with incomprehensibilities like SN1, SN2, E1, E2, δ+, δ-, you have Sir Christopher to thank.

Strictly speaking, though, no one really "invented" chemical theory. Neither Sir Christopher nor Sir Robert - who was the elder - were the first to start pushing electrons around. Like we said, the idea of electrons holding the molecules together in chemical bonds sharing electrons between atoms really began with Gilbert, and in particular there were two other organic chemists, both about ten years Sir Robert's senior, that were trying to work out the organic reaction mechanisms. One was Bernhard Flüscheim, a German chemist, and the other was Arthur Lapworth who was professor at Manchester (England) from 1909 until 1935. When Sir Robert became professor at Manchester (in 1922), he and Arthur would discuss their theoretical ideas and after lunch could often be seen sitting in the common room festooning structures and arrows all over sheets of paper.

In the 1920's, despite the real advancements made in the previous decade, chemists were still trying to figure out what went on in chemical reactions. True, with Gilbert's electron dot diagrams a lot of chemists were starting to think that the electrons were the major players in how one compound changed into another. That is, they believed movement and reorganization of electrons was what made reactions go. Others though, weren't sure, and some said flat out that the electrons had no importance in chemical transformations and that changes in molecules were rearrangements of atoms acting like charged spheres. Atoms sharing electrons? Pah! Not possible. Both Sir Robert and Sir Christopher, though, were strongly in the electrons-are-important-camp and they believed in covalent bonds - that is, bonding of atoms by sharing electrons.

Also it was during the 1920's when experimentally 1) it was becoming easier to deduce actual structures and 2) you could still make a lot of mistakes. Like many chemists then and now, both Sir Robert and Sir Christopher attended professional meetings, made presentations, and took part in the discussions. The meetings were a great place to toss out ideas before committing yourself in print.

There was one meeting in 1923 where Sir Christopher had made a presentation about his research. As Sir Robert sat in the audience, he thought something looked familiar. Surely Sir Christopher was espousing some of the ideas that he, Sir Robert, had originally proposed. Normally that's fine. Chemists are welcome to use what they've heard from others as long as you give the proper references. But Sir Christopher tossed no bouquets Sir Robert's way - or at least not enough bouquets for Sir Robert's satisfaction.

After the meeting Robert wrote and complained to Sir Jocelyn Field Thorpe (there's a lot of "Sirs" amongst England's chemists) that he had not been fully and properly credited for the ideas Sir Christopher had used. Sir Jocelyn, who had been Sir Christopher's Ph. D. advisor and a professor at Manchester when Robert was a student, replied (a bit airily perhaps) that he really saw no problem. After all, Sir Jocelyn soothed, everyone in the audience clearly recognized what parts of the talk were based on Robert's oft-repeated ideas. So there would be no harm, nay, no real need for Sir Christopher to explicitly reference Sir Robert.

Sir Robert was not convinced. And worse - at least in Sir Robert's opinion - was to come.

Nearly three years later - December 1925 - Sir Robert had submitted a paper to the Journal of the Chemical Society of London (now the Journal of the Royal Society of Chemistry). Sir Robert included some of his theoretical ideas in the discussion.

Now here's where it gets interesting. Later Sir Robert said that he sent Sir Christopher a copy of his article before it was published. That is, Sir Robert sent his younger colleague a preprint, a courtesy that is not unusual in scientific circles. And Sir Christopher, according to Sir Robert, replied with a warm letter praising Sir Robert's paper in general and the originality of the theory in particular.

However Sir Christopher had also written a paper - submitted actually two months after Sir Robert's. When Sir Robert read the paper, he became infuriated. Again he saw what he took to be his own ideas - and ideas from the preprint!

To Sir Robert everything was now clear. Sir Christopher had "stolen" his ideas. Certainly this is a harsh judgement but was the word used by some of Sir Robert's students to describe their boss's feelings - although not necessarily, we hasten to say, their own. But in any case, from then on Sir Robert detested Sir Christopher with unfeigned and undisguised bitterness and hostility.

And Sir Christopher?

We don't know what he felt because he never mentioned the matter. Even Sir Christopher's son, Keith (now an internationally famous chemist), said his dad never even mentioned Sir Robert. In fact, Keith said he hadn't even known who Sir Robert was until he reached grad school.

There is, of course, an obvious and non-sinister and highly probable explanation for the controversy. Sir Christopher was also developing his ideas on reaction mechanisms independently. We should remember that no one individual really started the pushing of electrons around. After all Sir Robert had been developing his theories working with Arthur. Sir Christopher, on the other hand, saw himself building on Bernhard's ideas (whom he did reference). So, although it's understandable that Sir Robert believed he saw his own ideas in Sir Christopher's work, it's equally understandable that Sir Christopher thought Sir Robert wasn't doing anything that he, Sir Christopher, and a lot of other chemists hadn't been doing already.

Now you can give priority to Sir Robert. After all he published his lectures in 1932, and Sir Christopher's definitive review appeared in 1934. But Sir Robert's pamphlet was - as even a post-doctoral student of Sir Robert described - published in a largely inaccessible form.

Also when the lectures were published, Sir Christopher was not even in England. Instead he was a visiting professor at Stanford where he began putting his theoretical ideas together for the Chemical Review article. Now Chemical Reviews was (and is) one of the major and most widely circulated (and surprisingly readable) chemical journals. The article contained Sir Christopher's theory and his notations were clearly and concisely explained. Except for the pamphlet, Robert's published theory was largely buried (often piecemeal) amongst his copious experimental data of his natural products research. But Sir Christopher wrote about reaction mechanisms where the theory was spelled out in detail.

Sir Robert's two lectures had, in fact, been his attempt to reclaim what he felt was his priority, but it wasn't until 1947 that he put his ideas together in a prestigious Faraday lecture. By then, though, Sir Robert's lingo had long been eclipsed by Sir Christopher's notations. So it's doubtful if the younger chemists could follow what Sir Robert was saying. Sir Christopher was in the audience, and as Sir Robert continued - blundered on, some might say - with his rather incomprehensible talk, a member of the audience saw a "Gioconda smile" - a nice way to say a smirk - fix itself on Sir Christopher's face. Sir Christopher would remain the King of Organic Theory.

Now what is interesting is that there is a story about when Sir Robert did not, well, "fully" attribute an idea. The American chemist, Robert Burns Woodward, had come onto the scene in the early 1940's and was also working on natural products including some that Sir Robert was interested in. At that time a lot of structures were still uncertain. The story we hear from RB was that he was at a dinner with Sir Robert. RB asked about a compound he, RB, was interested in and drew what he thought was the structure. Sir Robert, who actually had students working on the compound, snorted "That's rubbish! Absolute rubbish!". But a year later Sir Robert published a paper suggesting a structure. It was, yes, the same as RB had drawn - and which Sir Robert had dismissed as rubbish. RB was surprised.

R. B. Woodward

He was surprised.

And if you think that's interesting, long after RB was gone, another chemist later claimed about one of RB's most famous publications that RB had actually ....

Well, enough of this topic. We'll just say that questions of attribution and origins of chemical theories and ideas are often obscure and at times fraught with controversy.

More than 50 years after the first clashes (and when both men were no longer around) the Battle of Sir Robert and Sir Christopher was still raging on. One author wrote that there was no doubt that Sir Robert's notations and terminology was the superior. And another wrote that Sir Robert's language was "abstruse and sometimes obscure".

Guess who worked with who.

References

The Norton History of Chemistry, William H. Brock, W. W. Norton, 1993. A lot about the development of organic chemistry theory and specifics of the Sir Robert / Sir Christopher fracas.

From Chemical Philosophy to Theoretical Chemistry: Dynamics of Matter and Dynamics of Disciplines, 1800-1950, Mary Jo Nye, University of California Press, 1994. Again has a good discussion of the brouhaha.

"Robert Robinson: 13 September 1886 - 8 February 1975",

"Robinson, Robert." Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography, 2008. Retrieved September 16, 2014. Although some - quote - "informational" - unquote - web sites let anyone with no qualifications edit, revert, add, and delete, there are some others that adhere to proper academic standards. The CS of SB is one of those.

Two Lectures on an Outline of an Electrochemical (Electronic) Theory of the Course of Organic Reactions, Robert Robinson, Institute of Chemistry, 1932. As of this writing there was a copy of this publication available at reasonable enough cost.

"Introduction [to Issue Dedicated to Sir Christopher Ingold]", Keith Ingold, Bulletin for the History of Chemistry, Number 19, p. 1, 1996.

"Ingold, Robinson, Winstein, and I", Sir Derek Barton, Bulletin for the History of Chemistry 19 pp. 43 - 46, 1996.

"Organic Pioneer", Chemistry World, December 2008, pp. 50 - 53. A summary of Sir Christopher's achievements.

"The Origin of the 'Delta' Symbol for Fractional Charges", William B. Jensen, Journal of Chemical Education, 2009, 86, pp. 545-546

"Arrows in Chemistry", Abirami Lakshminarayanan, Resonance, 2010, pp. 51 - 63.