Will Rogers

And Some Quotes of Will

That Ain't NO Politician Gonna Use

Will Rogers

Everyone's Philosopher

The Wit and Wisdom of Will Rogers

Will Rogers was the first comedian to achieve worldwide fame and was the first "political" comedian as we know them today. Even now, fully eight decades after Will's untimely death on August 15, 1935 near Point Barrow, Alaska, the news media still posts his wry comments.

You know, we haven't got any business in those faraway wars. Seven thousand miles is a long way to go to shoot somebody, especially if you are not right sure they need shooting, and you are not sure whether you are shooting the right side or not."

And ...

There are still some folks working on arranging wars. England has strongly remonstrated with them and told them of the text in the Bible where it says "Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor's territory, nor thy neighbor's prospective oil wells, nor thy neighbor's natural resources! They broke out laughing and asked England's representative, "Where was that verse and chapter when you boys was coveting India, South Africa, Hong Kong, and all points East and West?"

Can any statements be more relevant today with the world's never ending conflicts, invasions for questionable and dubious causes, and with strong countries continually exploiting the poor simply for greed and political gain?

Truly, Will Rogers was a philosopher for all time!

Palatablizing Will

Now we have to reveal one of those deep, dark secrets that are often concealed from Will's modern day fans. Editors tend to be selective in what they print from Will's columns. Sometimes they even tweak - in other words rewrite - his sayings to make them a little more relevant - or perhaps "palatable" - for today's audiences.

For instance, let's consider the last two quotes. The first one we'll repeat in the form you'll find printed today:

You know, we haven't got any business in those faraway wars. Seven thousand miles is a long way to go to shoot somebody, especially if you are not right sure they need shooting, and you are not sure whether you are shooting the right side or not."

And what did Will really write in his 1932 column? Verbatim it is:

Floyd's main talk is that we haven't got any more business in these Far East wars than we had in the last European one [World War I]. He thinks seven thousand miles is a long way to go shoot somebody, especially if you are not right sure they need shooting, and you are not sure whether you are shooting the right side or not.

"Floyd's main talk is ..." "He thinks ...". What we see here is that Will is reporting the opinion of the (then) famous war correspondent Floyd Gibbons who had covered the then-recent Japanese invasion of Manchuria. Floyd had stopped by Will's California ranch and the men naturally turned to the possibility of American involvement. Note that Will himself is not taking any stand.

And the next quote? Remember it was:

There are still some folks working on arranging wars. England has strongly remonstrated with them and told them of the text in the Bible where it says "Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor's territory, nor thy neighbor's prospective oil wells, nor thy neighbor's natural resources! They broke out laughing and asked England's representative, "Where was that verse and chapter when you boys was coveting India, South Africa, Hong Kong, and all points East and West?"

So what did Will actually write on July 7, 1935? And just who are they?

There is no war going on at the present time. Paraguay and Bolivia just whipped each other. But there is an awful lot of folks working on arranging other wars. Mussolini sent his army down into Africa for a training trip hoping to annex some loose territory in route. That's your next war.

England was strongly remonstrating with Italy and told them of the text in the Bible where it says (I think it's the third chapter, third verse of the Book of Dutyrominy [that's how Will spelled it]) which reads: "Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor's territory, or thy neighbor's prospective oil wells, or thy neighbor's natural resources!

That's what England told Mussolini and Mussolini broke out laughing and England's representative didn't know what Mussolini was laughing at and he finally asked him and Mussolini said as follows,

"Where was the third verse or the third chapter of Dutyrominy when you boys was coveting India, South Africa, Hong Kong and all points east and west?"

Note again. Will himself is not taking a stand. In fact, the reader may wonder at what direction Will is actually tossing his barbs. At first, he seems to be shooting his arrows at the Italian dictator, Benito Mussolini, who was soon to invade Ethiopia in what became one of the harbingers of World War II.

But what does he do next? He points out that when the English built the Empire-On-Which-The-Sun-Never-Sets, they were doing the same thing as that war-mongering Mussolini!

What the hey?

Well, to (chuckle) clear things up, we'll throw in a few more of Will's quotes about Signore Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini. In 1926, Will not only visited Italy, but he met and interviewed the Italian dictator. Selected excerpts that flowed from Will's Remington Portable are:

That guy Mussolini is the smartest man in the world. Now I am not kidding, I honestly believe it. I have never yet, and I dare anyone to point out to me one move, or decree, that he has made that wasn't absolutely founded on common sense.

I have been in eight republics in the last ten days, including our own, and every one of 'em ought to be under Mussolini.

If he [Mussolini] died tomorrow Italy would always be indebted to him for practically four years of peace and prosperity.

You never saw a man where as many people and as many classes of people were for him as they are for this fellow. Of course he has opposition, but it is of such a small percentage that it wouldent have a chance to get anywhere even if they would let it pop its head up.

Dictator form of government is the greatest form of government there is, if you have the right dictator. Well these folks have certainly got him.

Yes, quote J is indeed an authentic verbatim stand-alone Will Roger's quote. Will really did say dictatorship is the greatest form government if you've got the right dictator.

And then he goes on and says the "right" dictator was Benito Mussolini!

Let's hear some politician give some of those quotes during his next campaign!

This ain't the Will Rogers we remember!

Will Rogers: The Minority Reports

But before we search for the Will Rogers we remember, let's look at the Will Rogers some of his contemporaries remembered. Two weeks after Will's death, an editorial appeared in one of the nation's top political magazines which at this writing is still going strong:

It was a striking fact about Will Rogers that millions of his admirers never realized the general direction in which his ideas pointed, or how little fundamental philosophy he had. His vivid likableness, his unfailing gift of humor, covered a multitude of sins.

He was in fact, in a fumbling and haphazard way, a truculent nationalist and isolationist of the Hearst school; he was Nietzschean in his ultimate reliance upon brute force. With his incessant hammering upon Congress, he probably did something to accelerate the decline of faith in the democratic process that has been seen in America in recent years.

He selected the object of his stinging barbs of wit with discretion; no one knew better than he which side of his bread was buttered, and how to make the butter coating thicker. What he did, of course, was to drift along with the currents of prevailing opinion in the groups where he found himself or to which he aspired.

Now equating the Philosophy of Will Rogers with kowtowing to the high and mighty seems incomprehensible to Will's fans who see him as a truly democratic gadfly, tweaking the noses of all politicians regardless of party. But worse, we see the editor is even lumping Will's politics with those of William Randolph Hearst - the Rupert Murdoch of his day - and even with the ideology of Übermensch German philosopher Frederich Nietzsche.

Such a dissenting opinion by no means vanished after Will died. A quarter of a century later, James Thurber - the famous New Yorker author of "The Secret Life of Walter Mitty" (made into a movie twice, the last time in 2013 with Jim Carrey) - wrote to a reader:

The point I have kept making about Mr. Rogers is this. He was not a genuine political satirist or a sound philosopher and the record of his writing stands there to prove it.

Read his book called "Letters of a Self-Made Diplomat to His President" which ran serially in the Saturday Evening Post in the middle Twenties. He kidded around with the awful Mussolini and wrote this: "Dictator kind of government is the best kind of government there is, if you have the right dictator, and these people have sure got him." That is from memory and may be slightly inexact in a word or two.

Will Rogers was a kidder, not a philosopher or a satirist. He was a great friend of presidents and vice-presidents, and senators and congressmen, and it doesn't take courage to kid your friends. I have nothing against him as an entertainer and a loyal American, but I am afraid that we have come to depend too much on the "aw shucks" philosopher in this country.

At this point we should remind everyone that James Thurber himself was famous and popular (and well paid) in his day. But he didn't have the phenomenal success of Will Rogers. So there might be just a wee bit of some sour grapes here. But at least we have reached a good place to begin the Quest for the Historical Will Rogers.

The Rogers: The Oligarchs from Oologah

We will not go into great detail about Will's life, but simply say he was born on November 4, 1879 on a ranch in Oologah, IT (that's "Indian Territory" for the cognoscenti) - which Will described as a suburb of Claremore. All his life Will signed hotel registries as "Will Rogers, Claremore, Oklahoma" because he figured no one could pronounce Oologah.

First let's get it straight. Will was not a poor farm boy. His dad, Clement Vann Rogers, was one of the richest ranchers in the territory. Clem wanted his son to grow up to be a business or professional man. But Will preferred riding and cowboying and, dang it, he just wasn't serious minded. He spent a good part of his time learning to handle a rope and became an expert even by cowboy standards.

Will's dad was concerned about Will's indifference to formal education, and in a last ditch effort to "straighten him out" (a popular expression particularly favored by baldheaded Oklahomans), he sent his "difficult" son to the Kemper Military Academy in Booneville, Missouri. Will's lackadaisical approach to schoolwork - not to mention his pranks and shenanigans - guaranteed he would not graduate, and he did not.

Now in his late teens, Will spent the next couple of years in Texas and Oklahoma (before 1907 still called Indian Territory) working on the ranches. Yep, Will Rogers really was a cowboy. He also competed in rodeos, and on July 4, 1900, at age 19, he won a steer roping contest in Claremore. Exactly a year later, he won another contest in Oklahoma City where he met the new Vice President, Teddy Roosevelt. Will soon helped organize and participated in other roping contests in Memphis, Tennessee, Springfield, Missouri, and San Antonio, Texas. These contests gave Will a taste of show business which he said was sure to ruin a man regarding honest work.

Stories about Will differ depending on your source, but everyone agrees that 1902 found Will and a friend in Argentina. Whether they were just working on the many ranches or actually trying to start a ranch themselves is a bit unclear. But Will soon sailed to South Africa.

An American cowboy in South Africa may seem strange to us, but at the time South Africa had a culture, apparel, lifestyles, and modes of transportation much like the American Old West. Many people also spoke English as well as Afrikaans. To see the similarities portrayed with reasonable accuracy, albeit stylized and in a fictionalized story, you might check out the 1961 film The Hellions.

But cowboying in South Africa had less appeal than in America - the country had cobras, not rattlesnakes - and Will's exceptional skill with a rope landed him a spot on Texas Jack Omohundro's American Circus and Wild West Show. Will decided to stick with show business and after working in a circus in Australia and New Zealand run by George and Phillip Wirth, he returned to the United States. In 1904, he was in Zack Mullhall's Wild West show which played at the St. Louis World's Fair.

In 1905, the show was at Madison Square Garden in New York City. During one of the matinees a steer broke loose and headed up the aisles. The story is Will lassoed the bull and saved the day. The resulting fame prompted Will to stay in New York when the show moved on.

Actually contemporary news stories of the event vary so much we can't tell what happened. Evidently a steer did break free and head up into the crowd. Will and possibly others (including future Western star Tom Mix) did attempt to rope the animal. It's anyone's guess whether Will's lasso brought the steer down or (as some accounts say) the animal came back to the arena on it's own accord. But it is true Will decided to remain in New York which at the time was the center of vaudeville.

Stories of how Will got to talking on stage also vary depending on the biographers. A common story is that Will was doing a rope trick but then the stunt went awry. So he began to explain what went wrong, and the crowd started to laugh. Will realized that it was his remarks and delivery that the audience found funny, not he himself, and he made the banter part of his act.

Another account is simply that Will's fellow performers suggested he introduce his tricks with a bit of patter. But whatever the story, Will's words became as important to the act as the rope work itself.

Luck was with Will. In 1915, Gene Buck, a junior partner and scout for Florenz Ziegfeld, the #1 vaudeville impressario, saw his act. Gene hired Will for a small production called the Midnight Follies. Then the next year he moved up to the big time Ziegfeld Follies which performed in the same building.

Then as now Americans loved passive entertainment. But if you wanted to sit around and be entertained you had to go to the entertainment. So a lot of the Follies audience were return visitors. They wouldn't laugh at the same jokes night after night, but Will found he could read the papers each day and keep the audience laughing just by talking about the day's events. The act was unique, and the critics raved about it. Will became a top headliner making a whopping $750 a week. But then things got even better.

The first two decades of the twentieth century was a time when technology was about to wreak its havoc on society in a manner which arguably surpassed the tumult of the late twentieth century computer revolution. Air travel was becoming commercial, and news events could be transmitted wirelessly across the Atlantic. Instead of going out to the theater, people were beginning to sit at home listening to the radio.

But above all, motion pictures were pushing live entertainment aside, and no one saw that quicker than Will. When producer Hal Roach offered Will a job in silent movies, he jumped at it. So in 1918, Will loaded his family onto a train - in 1908 he had married a girl from Arkansas, Betty Blake, and they now had three kids - and headed to Hollywood.

Will's movies were hits and although he was well-paid, he noticed that the producers were the ones raking in the really big money. So he decided he could be both actor and producer, and he set up his own production company.

Alas, Will was a good actor, but a rotten businessman. His movies lost money, and Will found himself in a debt so deep it seemed like he could never climb out.

Will returned to working for the large studios and to touring the country (vaudeville was not dead yet). He also began hiring himself out as a toastmaster and speaker at high-hat functions. And of course, Will turned to radio, appeared in newsreels, and slowly - as 60-Minutes host Mike Wallace put it - talked himself out of debt.

Not surprisingly Will made the transitions to talkies with ease, and soon he was one of the most popular actors in the world. Modern viewers should be warned that Will's performances will seem stiff, artificial, and unnaturally loud. This, though, reflects technology and style of the times. Film equipment was huge and bulky, and to adapt to the primitive sound technology, actors stuck to explosive stage delivery.

The topics of the films can also be disconcerting. At that time, audiences not only accepted but expected stereotyped characters that intelligent viewers today would - or at least should - reject completely. On the surface at least, some of Will's films make for painful viewing.

But it is Will's words that people still read. In 1919 the first book of Rogers-isms appeared, and in 1922, he began writing syndicated newspaper columns. He always thought it odd that if he misspelled words and garbled his grammar in private correspondence, it meant he was uneducated. But if he wrote the same way for a newspaper it meant he was a humorist. Soon across the nation everyone was reading Will's down-home humor about politics and current events.

Then in 1926 the Saturday Evening Post hired Will to travel around the world and write about what he saw. Will received $2000 - $4000 for each article which at the time was the price of a nice house. With his speaking engagements, articles, newspaper columns, and films, Will was taking in over $300,000 a year. Great money today; incredible money back then.

But then came October 29, 1929.

How did Will weather the depression? Actually quite well. He had never trusted stocks and had a natural disinclination in making money from such tenuous concepts as interest rates and dividends. Virtually all of Will's money went into land, and although he was a constant critic of spending money you don't have, the realities of real estate economics required him to purchase on mortgage. He built a large home in California on land which is now one of the nicer state parks. He also purchased land outside of Claremore where he planned to settle after he retired.

"Will Rogers would have said ..."

But let's get to the points.

First, was Will really an admirer of Mussolini and an advocate of dictatorship?

Was Will an isolationist and advocate of a nationalistic and Nietzschean philosophy of brute force?

We'll look at the last question first.

First, we need to determine exactly what the words "isolationism", "nationalism", and "Nietzschean" mean. That's easy enough:

isolationism: A policy of remaining apart from the political affairs of other countries.

nationalism: patriotic feeling, often to an excessive degree.

Nietzsche, Friedrich: German philosopher. He rejected Christianity's compassion for the weak, and formulated the idea of the Übermensch (superman), who can rise above the restrictions of ordinary morality. ■ Nietzschean.

- Paperback Oxford English Dictionary, 7th Edition, 2012, Oxford University Press

First things first. Was Will an isolationist?

Now you can find some definitions - also from dictionaries printed in England - that add that isolationism particularly refers to the policies of the United States. Although this may seem just a sneer from the stuffed shirt perfidious Albion, it is true that after World War I isolationism was seen largely as an American phenomenon. In particular, after the War, America refused to ratify the European negotiated treaties, and despite the best efforts of President Woodrow Wilson, never joined the League of Nations or the World Court.

The League of Nations, of course, was the first attempt at forming a United Nations and indeed after the Second World War, the League was replaced with that august body which we still have. The World Court - officially the Permanent Court of International Justice - was intended to rule on international disputes as the judiciary branch of the League.

And just what did Will think of these last two institutions? Certainly what he wrote wasn't particularly enthusiastic:

This World Court is up again. Some think it's great and some think it's terrible, and I am just one of the 90 percent of our population who don't know what it is. (1929)

Pardon me for bragging too quick. Just yesterday I said, "Hurrah for the U. S. She is spending her time solving her own problems." I wake up today finding we are trying to get into the World Court. My error. (1933)

Well, I get in here [Washington, D. C.] and what do you think I find this Senate arguing over? The World Court! Now I don't want to split the party, but the World Court is the deadest thing in this country outside of prohibition. (1935)

This last comment refers to the fact that with the rise of international tensions in the 1930s', fewer and fewer countries turned to the International Court to settle disputes. Certainly no one who read Will's words or heard his broadcasts thought Will favored joining the World Court.

OK. So Will didn't care for the World Court. Was that a problem?

To some in the administration it was. In fact, Cordell Hull, the Secretary of State for Franklin Roosevelt's first three terms, was particularly irritated by Will's comments. He later grumped that Will hadn't really understood the issues. Worse Cordell felt that it was Will's negative broadcasts that produced the flood of complaints to the Congress that actually derailed the Senate resolution needed for the US to join the Court.

Humph! The best laid plans of carefully negotiated diplomacy! And all derailed by (to use Cordell's words) a "cowboy philosopher"!

Regarding the League of Nations, Will wrote another book Rogers-isms: The Cowboy Philosopher on the Peace Conference. The title refers to the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 that ultimately led to five treaties with the enemy states - including the Treaty of Versailles with Germany - none of which the United States ratified. A typical Rogers-ism from the book is:

If President Wilson had any doubts about this League of Nations being put through he should have taken some of these Prohibitionists. They would have shown him how to get it through whether people wanted it or not.

Note that here - and in the authentic "faraways wars" quotes - Will does not directly give his personal opinion on the matter. Instead he makes comments designed to get a chuckle. But by linking the League of Nations with the Prohibitionists, he implies the League is something being forced on an unwilling public.

But if there's any question as to what Will's opinion was - and why - that's pretty much dispelled by his other writings:

So both individually and nationally we are just living in a time when none of us are in any shape to be telling somebody else what to do. That's why your League of Nations won't hold water; because the big ones run it, and the little ones know that the big ones have only turned moral since they got all they can hold.

So Will is what we might call a League skeptic. But note what else he said:

Now that [i. e., the League of Nations] may be a great thing and put properly in operation no doubt would, but why keep on trying it on the same voters who don't seem to want it.

So yes, Will was opposed to the League of Nations, but only as it was being implemented. He was by no means opposed to the basic idea. He even wrote some League of Nations was in fact a good idea if put "properly in operation". But Will saw this League of Nations as simply a machination of stronger nations to dictate their power over less powerful countries.

Whether you think Will was right or wrong, one thing the League did was allow England and France to divvy up the Ottoman Empire and so create the modern Middle East. France got Syria (which included Lebanon) and England got Egypt, Palestine, Jordan, and Iraq. Ostensibly this allocation was to reduce the power of the Ottomans - now reduced to Turkey - who had aligned themselves with Germany. The new "protectorates" were to be generously governed until the population was ready for full independence. In this way the - quote - "more civilized nations" - unquote - would be custodians for the less fortunate primitive societies.

Will, though, had his own ideas as to the real motives.

If England got Mosul [Iraq], Mosul must have had something that England wanted. You are right, Watson. What do you suppose Mosul had? Why Mosul must have had oil. That-a-baby Watson! You got it the first guess. Mosul had struck oil.

England hasn't lost a decision in that League yet. Well, why won't Turkey [Turkey owned the area of Iraq before World War I] fight for it? They will, just as soon as they get through with what wars they have on hand now. This is booked as their next war.

But I thought the League of Nations was to prevent wars.

We see then, that Will's - quote - "isolationism" - unquote - was an objection to larger superpowers (as we call them now) taking over the resources of other countries. His "isolationism" was also strongly connected with his opposition to military intervention. True, we saw how a later-day editor polished up his original "faraway wars" - quote to make it seem like an opinion of Floyd Gibbons was actually from Will. On the other hand, there is an authentic unedited quote where Will doesn't mince words. In 1927, he wrote:

China! Those poor people! I never felt as sorry for anyone in my life as I do for them. Here they are, they have never bothered anyone in their whole lives. They have lived within their own boundaries, never invaded anyone else's domains, worked hard, got little pay for it, had no pleasures in life, learned us about two thirds of the useful things we do, and now they want to have a Civil War.

Now, we had one and nobody butted in and told us we couldn't have it. China didn't send Gunboats up our Mississippi River to protect their laundries at Memphis or St. Louis, or New Orleans. They let us go ahead and fight.

This quote is, of course, specific to the beginning of the struggle between Chiang Kai-shek and Mao Zedong (then written as Mao Tse-Taung) that began in the 1920's. Several incidents had occurred where American missionaries had been killed and President Calvin Coolidge sent the gunboats and 1000 marines into Nanking.

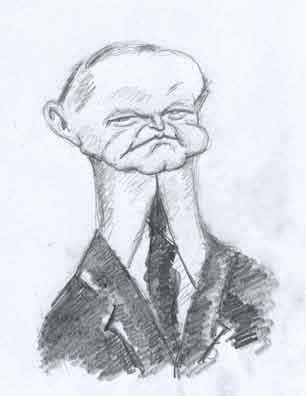

Calvin Coolidge

He sent in the troops.

Now some authors today say Will "questioned" America's intervention. But Will went further than simply questioning. In 1926, he wrote:

[Ohio State Senator] Carmi Thompson just returned from the Philippines. We are in wrong with them now. Why don't we give 'em [the islands] to them [the Phillipinos], and come on home and get our little Army together, and pass a law to never let them leave the country again?

Here it is pretty clear that Will is taking a stand that the US armed forces should stay out of other countries, period. And the policy should be even be mandated by law.

This brings us to the other criticism that his contemporary critics leveled at Will, that he tailored his comments to keep in good with his friends in high places.

It's kind of hard to agree. Will's continual criticism of military intervention certainly wasn't agreeing with the American government's - and Calvin Coolidge's - policy where intervention was becoming the name of the game. He was also at odds with a large chunk of the public who agreed with Calvin's policies.

But let's make this perfectly clear (to quote a US president). Will was no pacifist; no doctrinaire isolationist. He did not unilaterally oppose all wars. What he objected to were undeclared wars whose patriotic platitudes covered up dubious and ulterior motives. Or as he once put it:

Nations never seem to get much nourishment out of these unofficial invasions. If memory don't fail me I think we made a pilgrimage into Mexico unofficially. All we got was sand in our eyes. Either make it official and go in a shooting, or stay out!

Whatever private misgivings he may have had, Will publicly supported the First World War and contributed considerable time (and money) to aid the Red Cross. He believed Woodrow Wilson, who had campaigned on the platform of keeping the US out of the war, had made a difficult decision. So although he kidded Woodrow during a performance the president was attending - the first time a sitting US president had been "twitted" in person by a comedian - he did not make the war part of his routine.

Will and Edgar and John

So we see that it was far from true that Will simply stuck with the views of his friends in high places. Certainly he had no problems taking an "agin-the-government" stand regarding much of America's foreign policy. But he could be a pretty harsh critic on domestic issues as well. Consider what he wrote in 1934 about the rapidly rising J. Edgar Hoover.

J. Edgar Hoover

He turned down the silver.

On April 20, 1934, agents from Edgar's newly dubbed Federal Bureau of Investigation tried to arrest John Dillinger at the Little Bohemia Lodge in Manitowish Waters, Wisconsin. The agents ended up killing an innocent bystander and wounding two others while the crooks got away. Will wrote about this in his daily column:

Well they had Dillinger surrounded and was all ready to shoot him when he come out. But another bunch of folks come out ahead, so they just shot them instead.

Dillinger is going to accidentally get with some innocent bystanders some time. Then he will get shot.

Certainly in later years, such criticism of the FBI was something the Formidable Director wouldn't tolerate. Had Will lived longer he might have ended up being the subject of a bulging file in the cabinets of the FBI building.

But the only reference to Will in the FBI files was related to an invitation Edgar had received from the "Poor Richard's Club" of Washington, D. C. This was a civic group that recognized outstanding achievements of prominent Americans. Will had received a gold medal and the club was going to give Edgar a silver medal. Whether Will's higher status amongst the members was the reason or not, the agent writing the memorandum recommended Edgar not accept the invitation. He did not.

Will and Charles

In 1927, Will met the now famous aviator Charles Augustus Lindbergh and was the after-dinner speaker at a banquet given in Charles's honor. Will liked Charles immediately. After all, Will never met a man he didn't like, and Charles was an easy man to like.

Charles Lindbergh

He advised Will.

But then there was just one little thing.

In 1933, with the appointment of Hitler as Chancellor of Germany, the world started getting a sense of déjà vu all over again (to quote America's other philosopher, Yogi Berra). The tensions between Austrian chancellor, Engelbert Dollfuss, and the upstart Adolf Hitler - who thought Austria should be part of a Greater Germany - quickly escalated, and the various European countries began aligning themselves with the disputing parties. But at this time many Americans, not just Will, saw this as a European problem and in one of his columns, the title (probably created by the syndicate's editors) actually uses the "I" word.

Will Rogers Proposes a Policy of Isolation

Lotsa headlines today. "Mussolini's Troops Camped on the Austrian Border." "Hitler Says Nothing," which means that he is too busy moving troops. " England Lends Moral Support." Yes, and two battleships. "France Backs Austrian Government" and sends a few hundred planes over to deliver the message. "Japan almost on verge of prostration in fear Russia won't get into this European war,"

Mr. Franklin D., shut your front door to all foreign ambassadors running to you with news. Just send 'em these words:

"Boys, it 's your cats that's fighting, you pull 'em apart."

So we see that Will definitely thought America should remain apart from the new conflicts breaking out in Europe and Asia. And such views were labeled - even by Will's own editors - as isolationist.

Now we have to remember. This column was written in 1934 when Hitler had been in power barely a year. At that point, no one anticipated what was to come and the American public - and FDR - did not want to intervene in what was seen as an Austrian-German problem.

But as the 1930's rolled on, things changed. Hitler invaded the Sudetenland, took over the rest of Czechoslovakia and effected the Anschluss of Austria and so brought on the Kristallnacht pogrom. In 1939 there was a Life Magazine article on the German concentration camps (complete with pictures) and then in September 1939, Germany invaded Poland. England declared war, and then followed Germany's blitzkrieg attacks on France, Belgium, and the Netherlands and the occupation of Norway and Denmark. World War II was on.

For Charles there was only one way for America. At the very least he wanted neutrality with Germany, and at best he wanted firm friendship. He had visited Germany in the late 1930's when the US government had asked him to look into Berlin's emerging air power. Charles had been impressed with what he saw. He also liked the German people and according his own letters and DNA tests, he liked some of them way too much. A plan to buy a home in Germany, though, was scotched as anti-German sentiment grew in America.

But even with the declared war between Britain and Germany, Charles stood firm and urged a negotiated settlement. He quickly became one of the most popular speakers for the organizations advocating neutrality, the most famous of which was the "America First Committee".

In fairness to Charles, in his speeches he spoke against the persecution of the Jews in Germany and said he understood why Jewish Americans wanted to support Britain. But toleration, he said, would only come by peaceful means. So the Jewish community, he argued, should oppose any war with Hitler. Then in what can be classified as a major faux pas, Charles added that the Jewish people were being duped by their own leaders who he asserted were in control of America's media.

Now, some of Charles speeches were well thought out - we hear he labored hours writing them out. But soon his speeches began to become increasingly strident and even odd. He said that the elected government in America didn't represent the will of the people (a common complaint of smaller political groups), that free speech in America was dead (an odd comment to make by someone giving nationally reported speeches criticizing the government), that he, Charles, was better qualified to speak for Americans that the President (questionable as FDR was into his second term of eventually four elections), and that it was really Franklin Roosevelt who wanted world domination (the old rhetorical trick of cross accusation). Charles even suggested Roosevelt might cancel the 1942 elections (he didn't of course).

Above all, Charles wanted a ban on any offensive weapons sold to Britain. Then in a big faux pas - the worst of his career - he testified before Congress that it made little difference whether Britain or Germany won the war. What the heck, Britain was going to lose, anyway, and so American assistance would simply be prolonging the agony.

From 1936 to 1939, Charles and his family had lived in England and had made a lot of friends. Now they were his former friends, and they were flabbergasted. By the fall of 1941, Charles had become persona maxima non grata both in England and in the Roosevelt administration which had been supplying Britain with much needed war materièl. FDR had also been gearing up our own industries - and rapidly ending the Depression - for a war which almost all Americans now saw as inevitable.

For his part, FDR made his own speeches where he specifically called Charles to task. His remarks were so strong that Charles felt no choice but to resign his colonel's commission in the Army Air Corps Reserves.

Of course, isolationism vanished with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and Germany's subsequent declaration of War on the United States. Like virtually all Americans, Charles wanted to join the fight for his country. Normally that would have been no problem. At age 39, Charles was not just eligible for military service but he was even subject to the draft. But his attempts to rejoin the Army Air Corps or otherwise serve were stymied by FDR who was still extremely annoyed with Charles.

However, by now Charles had become one of the nation's leading aviation experts. He knew how planes worked and what made them fly better. At first and unbeknownst to FDR, the Navy brought Charles in as a consultant, and in 1944, the Air Corps asked Charles to do a tour in the South Pacific. Officially Charles was a civilian observer. That meant he could go along on missions but not engage in actual offensive actions. He could, though, take actions in self-defense.

Yes. But of course, if you're an "observer" in a single-seat combat airplane, well, you have to fly it yourself. And of course, if you are prepared to defend yourself, you have to have all the armament of a combat plane. And there's no point of having all those weapons and not use them - for defense, of course.

Of course.

Fact is, Charles flew 50 combat missions during the Second World War, all the while officially a civilian. He did surprisingly well although once he couldn't understand why he couldn't keep up with the other pilots until one of them radioed that Charles had forgotten to retract his landing gear.

Only in recent years has it become one of the "facts-you-never-knew" that Charles had advocated a negotiated settlement with Germany and American neutrality. After the war, Americans were more than willing to forgive and forget. Charles remained America's #1 hero, and President Dwight Eisenhower restored Charles's Air Force reserve commission and promoted him to brigadier general. Then in 1953 Charles wrote a book about his famous flight which won the Pulitzer Prize. The book was made into a movie - a box office flop by the way - with the 48 year old Jimmy Stewart playing the 27 year old Charles. Today Charles's plane, the "Spirit of St. Louis", remains one of the most popular exhibits at the Smithsonian Institution's National Air and Space Museum.

Ironically, what people see as Charles's greatest achievement - that he was the first man to fly across the Atlantic - is not what he did. He was the first person to make the trip solo and non-stop. What's really funny is that almost as soon as he got back, people quickly forgot about the previous non-solo flights between the US and Europe. Within a few months of Charles's return, artist and columnist Robert Ripley pointed out that Charles was actually the sixty-seventh person to fly across the Atlantic. Of course, Robert was also counting flights of dirigibles and received many a spittle-flinging diatribe from affronted readers.

Charles was one of the unusual people who felt that technology and preserving natural resources and the environment were not mutually antagonistic. He became a strong conservationist and environmentalist. However, he largely kept out of public view, and when he died in 1974, many people were surprised to learn he had still been alive.

But we wonder. Will, of course, was no longer around after 1935. But given his strong anti-interventionist stands in the past, would he have joined with Charles in urging neutrality with Germany? Although Michael Korda, the biographer of Lawrence of Arabia, has pointed out that no historian should ever speak for his subject, we will still hazard a guess.

Hitler doesn't appear much in Will's columns, understandable since in 1935 Hitler had been German chancellor for only two years. At that time many people still saw the German dictator as a carpet-chewing buffoon rather than the future mass genocidal murderer who would occupy 90% of Europe and order the Endlösung.

But from the first Will saw through Hitler's racial and anti-Semitic ideology. As he wrote in 1933:

Papers all state Hitler is trying to copy Mussolini. Looks to me like it's the Ku Klux Klan that he is copying.

Needless to say, Will despised the Ku Klux Klan.

Also in asking if Will would have "joined" Charles implies that those who opposed intervention shared a common ideology or philosophy. Nothing could be further from the truth. There were not only people like Charles who wanted a negotiated peace with Germany, but there were non-interventionists who despised Hitler and wanted him defeated. They hoped that by supplying arms to England, England would defeat Hitler, without another World War. Given Will's staunch non-interventionist philosophy of the past and his opposition to Hitler, we hazard he would have agreed with the latter group - until Pearl Harbor.

Will Never Met a Man He Didn't Like?

But we also see Will's last quote brings us back to Benito.

We've seen it's understandable and probably justified - although somewhat simplistic - for people to see Will as an isolationist. On the other hand, with Will's continual hammering on American foreign and domestic policy and those who formulate it, he was about as far from being a nationalist or a Nietzschean as you can imagine. In fact, he was, if anything, an anti-Nietzschean who believed it was the ordinary people who had the right ideas, not any hypothetical Übermenschen.

But what about the claim of Will's "ultimate reliance upon brute force"? Well, this does have something to do with Mussolini.

Benito Mussolini

A Man He Didn't Like?

In fairness to Will, the Benito the world saw in the 1920's was not the Il Duce they saw in the mid-1930's and later. Will's comment was also apt. Far from seeing Mussolini as a watered down Italian imitation of Adolf Hitler, people thought it was Hitler who was trying to ape Benito. And - very strange for modern readers - until October, 1935, two months after Will's death, Benito actively opposed Hitler and Germany's first attempt to take over Austria. As the Depression worsened, many Americans, not just Will, saw Benito as a strong leader of the type America needed and the Italian dictatorship as relatively benign.

After his 1926 interview with Benito, Will wrote up his visit in an article to the Saturday Evening Post. To call Will's visit an interview, though, requires a bit of hyperbole. "Chat" is more like it. Benito's English wasn't great (as some famous newsreels show), and for answers of any length, he spoke through his interpreter. Reporting the so-called interview took up little more than a paragraph in an otherwise lengthy article.

Instead Will spent much more time writing about Benito. We must be very honest and say the comments in the article approached hagiography. Will's positive assessment of Il Duce in the Post was also no one-time minor aberration. For the next several years, Will's comments about Benito were almost exclusively laudatory.

It wasn't just the praise for the Italian dictator in the Post article that raised concerns about Will's "ultimate reliance on brute force". There is one passage that was particularly worrisome:

Now as to what will happen when he [Mussolini] is no more, why of course no one can tell. But as I said before, he is trying to so perfect the thing that it will go along without him, the same as our founders made our Constitution almost foolproof.

Then you don't want to forget that that castor oil will live on after he has gone, and that, applied at various times with proper disscretion [again a sample of Will's spelling], is bound to do some good from every angle.

A reference to castor oil and Mussolini is so obscure today that it requires considerable elaboration, while to readers in Will's time it was so obvious as to need no explanation. But it was such a reference that caused the angst and led to the comment about "brute force".

At this point we need to have a pause - not that refreshes but digresses - and see what Benito had to do to come to power. Or rather we ask, just how the heck did a former elementary school teacher and draft dodger, who in 1919 was scraping around by writing piddly-ant newspaper articles, end up being Italian dictator by 1922?

Benito: From Insegnante to Duce

Italy had been on the winning side of World War I, but by 1920 the windfall of war had been divvied up between America, England and France. England and France continued to expand their empires by grabbing up the Middle East. For America, the war led to the boom times of the Roaring Twenties and the nation's emergence onto the international stage fully on par with the two traditional Empire builders.

But in Italy, economic recession set in, and the people thought the government was being run by a bunch of jerks. Poor farm workers - the "peasants" - were banding together and threatening to seize land from the wealthy land owners.

Things were even worse in the cities. There the urban workers had already began taking over the factories. And with the Bolsheviks winning out in Russia, the fear of Communism was becoming acute.

As part of the anti-Communist struggle, the wealthy businessmen and land owners hired the newly discharged veterans of the Italian armed forces - particularly the elite Arditi troops - as private police forces. Riots had broken out, and civil war had become a real possibility.

Now Benito had started out being a socialist, championing the shop owners, the peasants, and the factor workers. But seeing the way the wind was blowing, he switched to being a free market man for the agriculturalists and the industrialists. Venting his views in a newspaper with a somewhat contradictory name, Il Popolo, Benito proposed a simple solution to Italy's ills.

Why, just make him dictator - Il Duce - and that would solve everything. And to avoid divisive factionalism - which as we know can produce long term political gridlock - there would be only one party, the Facisti - a name Benito borrowed from the Roman fasces the bundle of rods signifying the imperium of the Roman leader. If you want to see a picture of the fasces, you can look at the speaker's platform of the United States House of Congress.

As odd as it is that a bald headed cafone who had never held political office would be demanding to be put in charge of a country, Benito was making the mainstream Italian politicians decidedly nervous. So in 1920, the Italian prime minister, Giovanni Giolitti, had a brilliant idea. True Benito had never held office, but growing numbers of his Facisti even now were sitting in the parliament. Giovanni would ask them to form a coalition and he, as prime minister, could control them.

The coalition was fragile and by 1922, the country was still in chaos with riots between the Fascists and other parties taking up a lot of the time. The coalition fell apart, and Benito said he and his followers were going to march on Rome.

As it turned out, the march turned out to be unnecessary. King Victor Emmanuel III summoned Benito to Rome and asked him to serve as prime minister of a new parliamentary government. Benito became prime minister and hey, presto!, he did away with rival political parties, got himself voted absolute powers, and claimed to have made the trains run on time. Ironically during all this time, Italy was (nominally) ruled by a king, and for what it's worth, in 1943 it was King Victor Emmanuel who informed Benito he had been deposed.

But what does all this brouhaha have to do with Nietzsche, brute force, and castor oil?

In mentioning castor oil, Will is specifically referring to a tactic that Mussolini's Fascist gangs used against their opponents. After a riot or other violent confrontations, Benito's gangs would force a quart of castor oil down their prisoner's throats. The tactic was also used on otherwise peaceful citizens who publicly defied the Fascists. The physiological effects of this foul tasting "treatment" - although in these enhancedly interrogative days is sometimes referred to in a humorous manner - were debilitating and even dangerous.

But castor oil was then - not so much today - also used as a treatment for stomach ailments if taken in teaspoon quantities. So in effect, Will's remark on castor oil was not only glossing over the turmoil that brought Mussolini to power, but was implying that in the right amount, the violence was beneficial since it ultimately brought Italy peace and prosperity. Hence the remark about Will's "ultimate reliance upon brute force".

Will and Benito: The Later Years

So what would Will have thought about Benito had he lived to World War II? Well, there's not much doubt about that. Even as the mid-1930's approached, Will began to have serious doubts about the man he saw hobnobbing with Hitler and sending his troops to other countries - something that was always a red flag with Will. His later comments make clear his changed opinion.

Well, there ain't much news till we get the dictaphone records of what Mussolini and Hitler really talked about. They may have never said a word about France but you will never make France believe it. (1933)

We had heard of all kinds of likely wars between nations, but this one that Mussolini dug up is a new one. Italy versus Ethiopia. That's going a long way for an enemy. (1934)

Not a Stalin, not a Hitler, not a Mussolini to mar the proceedings. (1934)

By the end of World War II Will had emerged as an iconic and even legendary figure. His name was plastered everywhere - from charities to convenience stores to mom-and-pop restaurants to schools to movie theaters. There was even a church named after him, for crying out loud! Articles about Will proliferated in newspapers and in nationally circulated magazines.

But his past praise of Mussolini was a topic tacitly not up for discussion. Even today you'll most likely draw expostulations of disbelief if you even mention the subject. Scholars, though, are well aware of the embarrassing bouquets Will tossed toward Benito and understand if you're going to be accurate, you can't sweep it under the rug.

We must repeat. Today the world sees Mussolini as the strutting jutted-jawed stronzo that emerged in World War II, but in the 1920's and early 30's, there were many Americans that yearned for such a leader. Will had seen how hard it was for the United States with its ever changing administrations and shifting polices, to focus on a solution for its problems. So he fell into the idea that a benign dictator was a real option, and in the 1920's he thought such an institution had arisen in Italy. Of course, there is no such thing as a benign dictator, and that was one thing, as the author of Will's definitive biography mentioned, that Will got wrong.

Will and the Russian Experiment

OK, Will got the bit about Benito wrong. But what did Will get right?

Russia. That's what Will got right.

In 1926 - during the same trip where he went to Italy - Will visited Russia. The Tsar had been deposed in 1917, but the Soviets had only been in full power for four years. People were looking at Russia with a lot of interest: some with fear, some with hope, and a lot with curiosity.

In the years immediately following the revolution, Russia had not yet become a closed society. As long as you had the money to travel, you could get in and get out easily enough. Composers like Stravinsky and Prokofiev were in Europe and America, and Soviet physicist George Gamow had discovered the key to radioactive decay while studying with Niels Bohr in Copenhagen. So if Will wanted to go to Russia, he could.

The trouble was the United States would not recognize the Soviet government until 1933. But on the other hand, they didn't specifically prohibit its citizens from going there. As Perchik said to the rabbi, if it's not forbidden it must be alright. But Will had to get his visa in England.

Will went to Russia with an open mind. He was certainly willing to give the country and its leaders a chance. If the Revolution worked, fine. But if it didn't, so be it.

Will wrote up his trip in a book, There's Not a Bathing Suit in Russia published in 1927. The title is from the time Will saw a bunch of swimmers on the Moscow River. There were - literally - no bathing suits. As Will described it:

They just wade in what you would call the Nude, or altogether. No one-piece bathing suits to hamper their movements.

Well, when I saw that I just sit right down and cabled my old friend Mr. Ziegfeld: "Don't bring Follies to Russia. You would starve to death here."

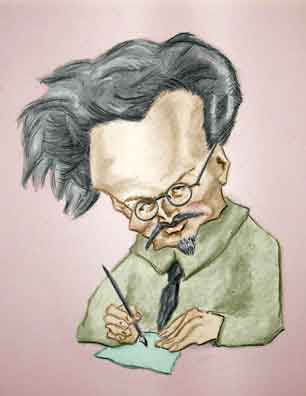

Leon

On Will's Must-Meet List

The one person on Will's "must-meet" list was the Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky. The meeting, though, never came off. Leon, originally seen as the most important of the successors to Lenin, had been shoved aside by a former divinity student, weatherman, and bank robber named Iósif Vissariónovich Dzhugashvili, who even then had taken the more pronounceable name of Stalin. Will never met either man.

There's Not a Bathing Suit in Russia is one of Will's more amusing books, but overall, Will was far from impressed with what he saw. The ideas of the Communists, which had looked so good on paper, just didn't work out in practice. Life, Will thought, was no better than than under the Czars, and in some ways it was worse.

Of course, Will wrote up his opinion as typical Rogers-sims.

You see, the Communism that they started out with, the idea that everybody would get the same and have the same - Lord, that dident work at all.

Russia hasent changed one bit. It's just Russia as it has been for hundreds of years and will be for the next hundreds of years.

Russia under the Czar was very little different from what it is today; for instead of one Czar, why, there is at least a thousand now.

Siberia is still working. It's just as cold on you to be sent there under the Soviets as it was under the Czar.

Communists have some good ideas, of course; but they got a lot that sound better than they work.

As much as people - even in Russia - agree with Will today, in the 1920's and 30's a lot of people saw Russia as the way of the future. Even as late as the 1940's Life Magazine could get away with writing a now laughable article - complete with photographs of happy smiling collective farm workers - about how great it was to live in a country run by Uncle Joe. But Will - like philosopher and mathematician Bertrand Russell who also saw Russia firsthand - remained decidedly unimpressed.

Everyone's Philosopher

Will's wit and wisdom has achieved such iconic status that today we're supposed to accept any quote by Will as we would a saying by George Washington or Abraham Lincoln. That is, without thought or question. To do otherwise would be un-American.

Best of all, anyone can quote Will. You can be a Marxist Socialist or an Adam Smith Free Marketer or even a Muddle-With-The-Economy John-Maynard-Keynesian, and you can pluck out a Rogers-ism. And it's even easier if you're going to rewrite it anyway.

Of course, you have to be very selective - even with Abraham and George. For instance, do you think a politician today would trot out this quote of Lincoln:

I will say then, that I am not nor ever have been in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races ... that I as much as any other man am in favor of the superior position being assigned to the white man.

Yep, Lincoln - Abraham Lincoln - that's the Abraham Lincoln - made that statement September 18, 1858 in Charleston, Illinois before a crowd of 12,000 people.

Out of context? Not at all. Lincoln was in fact answering the question - that Stephen Douglas raised - if Lincoln favored equality of and granting full citizenship rights to all Americans regardless of race. At the time that was a radical viewpoint, and Lincoln - always a politician - denied it was true.

And George? Let's give you a quote from May 31, 1779 to General John Sullivan. George was instructing how John should proceed with the Native Americans.

The immediate objects are the total destruction and devastation of their settlements, and the capture of as many prisoners of every age and sex as possible. It will be essential to ruin their crops now in the ground and prevent their planting more.

But you will not by any means listen to any overture of peace before the total ruinment of their settlements is effected.

First in war, evidently. But clearly not first in peace.

So what do we make of Will?

First, Will was an entertainer. His job was to make people laugh and like our topical comedians today, he would say different things at different times. He could praise America as a land of opportunity and its government as the best there is. Then he could say a dictatorship under the right dictator was the best form of government. And even Will warned people about taking what he said too seriously.

Enough said.

Will and Wiley

Will took his first plane ride in 1915 and loved it. Although Charles Lindbergh once cautioned him to stay out of single-engine planes, Will became a vocal and enthusiastic promoter of aviation. Then around 1925, he met Wiley Post.

Wiley and Will are usually referred to as fellow Oklahomans, but Wiley was actually born in Texas. He left school after the seventh grade and while watching some airplanes at a local airport, he decided he wanted to be a pilot. But to learn to fly cost money and owning a plane cost even more. So Wiley took jobs as a roustabout in the burgeoning oil industry. Then when an oil field accident cost Wiley his left eye, he used the settlement money to buy a plane.

Wiley became one of the first commercial pilots in America, flying for a rich Texas oilman. He also entered - and won - national airshows and races and quickly gained fame as a pioneering aviator. He tested pressure suits for high altitude flights and managed to reach 50,000 feet. Wiley is also given credit as one of the first pilots to recognize the jet stream for what it was and how it could work for and against air flight.

In 1931, Wiley and navigator Harold Gatty claimed the speed record for flying around the world: 8 days, 15 hours, and 51 minutes. Then in 1933, Wiley claimed the first (and hence fastest) solo flight around the earth, 15,596 miles in 7 days, 18 hours, 49 minutes (some say 49 1/2 minutes, but who's counting?).

Alas, there's one bit of information you never read in the bios of Wiley. The distances he flew are way, way too short to qualify as a circumnavigation. His latitude was too high. To qualify for flying around the world, you have to fly past each meridian of the globe but also have to travel the length of the Tropic of Cancer - 22,858.729 miles. There are other details, such as staying out of the Arctic or Antarctic circles. So no, you can't claim a circumnavigation by going to within 850 feet of the North Pole and circling it 22,599 times.

In 1935, Wiley was trying to map out an airmail route though Alaska to Russia. But despite his fame, he usually had trouble drumming up funds for his projects. And although FDR had officially recognized Russia in 1933, arranging a visit to the now Stalinist country was almost impossible.

But Will thought Alaska would be a great place to pick up new material for his columns and told Wiley he'd put up the money. And even Russia couldn't turn down a request from Will Rogers. So the ambassador at San Francisco issued visas for both men.

Wiley flew a Lockheed Orion 9E that he had modified for extended flight times and to land in water. This was not a small plane. The Orion was actually one of the early commercial airliners with a back cabin that could accommodate a whopping six passengers.

Naturally the accounts of what actually happened vary. Everyone does agree that Wiley got lost due to fog and landed in a small lagoon called Walakpa Bay. He taxied the plane over to where the family of Claire Okpeaha, one of the native Inuits, had camped while hunting seal and walrus. Wiley called out for directions to Barrow. Clare pointed northeast and said it was 15 miles (it's actually about 12). Wiley thanked him and took off.

Almost as soon as the plane was in the air, it turned nose down and flew into the water. Both Wiley and Will were killed instantly.

Some newspaper reports mention that after Wiley landed, he and Will deplaned and came to shore. As Clare's English was limited, Stella, his wife, gave the men directions. Some stories also mention the plane had engine trouble, and Wiley worked to fix the engine. After having dinner with the Okpeahas, both men then got back in the plane. Then at 50 feet - or perhaps 60 - or 100 - the plane stalled and plunged nose down. The plane flipped and ended upside down in 2 feet of water.

To this day no one knows what caused the crash. Most stories mention a stall which usually means a loss of lift due to low speed or too steep an angle of the nose. However, the primary fuel tank was found almost empty. The usual procedure was to use all the gas in the first tank before drawing on the reserves. Even in mid-flight, the switch-over was not a problem.

So what may have happened is that when Wiley took off, the fuel fell away from the intake line to the carburetor. Deprived of fuel, the engine failed, and because of their low elevation, Wiley didn't have time to switch tanks or level the plane for a belly landing. Also a lighter craft might have helped with Wiley gliding down.

Claire ran the distance from Walakpa to Barrow, reaching the settlement in about two hours. A rescue team quickly made it to the crash site.

Wiley was found completely submerged and inside the plane. His watch had stopped at 8:18 (p. m.). One story said Will had been thrown from the plane, but other accounts stated that the Inuits had been able to pull him from the cabin. The latter story is the more likely. But whatever happened, Will, too, was dead. His watch was still running.

References and Further Reading

Will Rogers: A Biography, Ben Yagoda, University of Oklahoma Press, 1993.

Will Rogers' World: America's Foremost Political Humorist, Will Rogers, Bryan Sterling, and Frances Sterling, M. Evans and Company, 1993. Accurate quotes, largely from Will's writings, with commentary.

Will Rogers: A Political Life, Richard D. White, Jr., Texas Tech University Press, 2011.

"The Legend of Will Rogers", Roger Butterfield, Life Magazine, pp. 78 - 94, July 18, 1949.

The Papers of Will Rogers, 6 Volumes, University of Oklahoma Press, 1996 - 2006. Probably the best source regarding availability and price, although there naturally is some selectivity to keep the size down.

The Writings of Will Rogers, Will Rogers, 1973 - 1983, 21 Volumes, Oklahoma State University Press. If Will wrote it, it's bound to be here.

The Writing of Will Rogers, Will Rogers, http://www.willrogers.com/papers/intro.html. The online edition but by no means as extensive as the hard copies.

"Letters of a Self-Made Diplomat to His President", Will Rogers, Saturday Evening Post, pp. 82-84, July 31, 1926. The letters were collected in the book, Letters Of A Self Made Diplomat to His President first published by Albert and Charles Boni, Inc., in 1926.

Rogers-isms: The Cowboy Philosopher On Prohibition, Will Rogers, Harper and Brothers Publishers, 1919

When the Laughing Stopped: The Strange, Sad Death of Will Rogers, John Evangelist Walsh, University of Alaska Press, 2008. Will's and Wiley's deaths were sad, yes, but not particularly strange, and this short book was researched using primary and contemporary accounts. Unfortunately, the book's usefulness is somewhat tempered by the author's extensive use of created scenes and invented dialog (although the term used is "reconstructed"). A much more useful book - and perhaps more suited for a university press - would have had more discussion of the variant accounts which here are limited to the usually brief and sparse footnotes.

"Will Rogers, Post Die in Crash", Frank Daugherty, United Press, 1935.

"Anniversary of Death : Will Rogers - a Mirror of America", Jerry Belcher, Los Angeles Times, August 15, 1985

Creating America: George Horace Lorimer and the Saturday Evening Post, Jan Cohn, University of Pittsburgh Press, 1989.

The Thurber Letters: The Wit, Wisdom and Surprising Life of James Thurber, Rosemary Thurber, Simon and Schuster, 2003

"Will Rogers: Forgotten Man", Ivie Cadenhead, Jr., American Studies 4(2), pp. 49-57, 1963.

Will Rogers, Brian Lamb Interview with Author Ben Yagoda, C-Span, 1994.

Mussolini and Fascism: The View from America, John Patrick Diggins, Princeton University Press, 1972

"Charles Lindbergh: A Stubborn Young Man of Strange Ideas Becomes a Leader of Wartime Opposition", Roger Butterfield, Life Magazine, pp. 64 - 75. August 11, 1941. If not exactly a neutral article - no double intended - on Charles' political ideas, personally the write up is by no means negative. It mentions Charles respect for nature and the environment, an occupation to which he devoted his later years.

"America First Roughhouse", Roger Butterfield, Life Magazine, p. 40. October 21, 1941. There's not much doubt about Life's editorial position on the soon to be American war. They did not agree with Mr. Lindbergh.

"Charles Lindbergh: Hitler's All American Hero", Paul Callan, Daily Express, September 24, 2010. A decidedly negative article about Charles but it does cover the controversy regarding his advocacy of neutrality. For his own part Charles later stated he was not anti-Semitic and his wife, Anne, said he even supported creation of a Jewish homeland.

"Re: Poor Richard's Club", FBI Memoranda, T. W. Dawset, October 19, 1936, Addendum, R. C. Hendon, Octobr 23, 1936., Letter to the Director of the FBI, R. E. Vetterli, October 21, 1936". These memos - one which advises Edgar not to accept the invitation and accept the Silver Medal from the Poor Richard's Club (which had given Will the Gold Medal) - are currently on the FBI's Vault webpage.

1920: The Year That Made the Decade Roar, Eric Burns, Pegasus, 2015.

"Murnau, Movietone, and Mussolini", Janet Bergstrom, Film History, Volume 17, pp. 187-204, 200. An article about the British film company's newsreel of where Benito makes a friendly greeting to America and in English.

Internet References

There are, of course, many references to Will Rogers on the Fount of All Knowledge that we call the Internet. But as always be warned! On one popular informational web site, there is an article on Mary Howard Rogers, later Mrs. Alfred de Liagre Jr. Mrs. de Liagre, we read, was the daughter of Will Rogers, and she was born in Independence, Kansas and died in 2009. Actually, this article is confusing the two ladies. Will's daughter was Mary Amelia Rogers, was born in Arkansas (where Betty, Will's wife, was from), married a man named Brooks, and died in 1989. The two ladies are not the same.

"On this Day", Robert Kennedy, The New York Times, September 15, 2001, http://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/harp/0915.html.

"Wiley Post and Will Rogers, Lockheed Orion 9E, NR-12283", August 15, 1935, Don Jordon, http://www.donrjordan.com/.

Will Rogers United Methodist Church, http://www.willrogersumc.org/ We were not joking. The church that adopted Will's name was established in 1943 and is still going strong.

Movietone Digital Archive, http://www.movietone.com. Mussolini made more than one newsreel in English and they can be found on this site. We have to say that Benito speaks in English, but we also note how the Benny of the late 1920's and early 1930's did not project the same image as the Il Duce of 1941. We also have to say, as Will found out, that Benito's English was rudimentary, and it's a good bet he is reading from idiot cards.

Charles Lindbergh, http://charleslindbergh.com. A website about Charles Lindbergh with good detail about his life. It doesn't skirt the controversy of Charles's stand on neutrality with Germany, and also includes a good account of his service to the US Army Air Corps during World War II.

The Hellions, Director: Ken Annakin, Irving Allen Productions, 1961. The Hellions is set on the South Africa frontier in the 19th century. The moniker, the Hellions, was actually a nickname bestowed on the bad-guys, the Billings father and sons, by the townspeople. The few people who've seen this movie are struck by it's similarity to High Noon, but also by it's catchy theme song written by Herbert Kretzmer and Larry Adler and sung by British pop singer Marty Wilde (who also played, John Billings, one of the bad guys).