Before and After

Henry VIII: Before and After

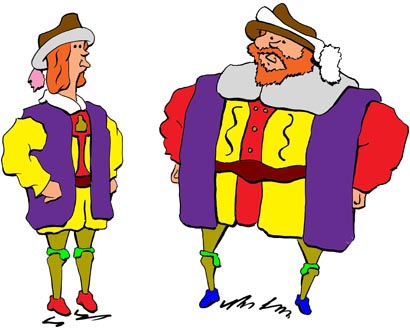

Historians used to write that Henry VIII was the biggest jerk who ever sat on the English throne. He was a brutal despotic tyrant with absolutely no redeeming qualities and was a big fat slob who jumped from wife to wife, chopping their heads off when they displeased him, and ended up dying a vast wobbling mound of lard.

But assistant professors of history have to make a living, too, and each generation of scholars comes up with new interpretations that older historians were just too dense to recognize. So today you'll read that Henry was a "complex" man who when young was tall, slim, and handsome. He was an expert horseman, a highly skilled hunter, and a superb athlete who won many a joust and was one of the finest archers in the land. But Henry was also a political innovator whose governmental reforms were the beginnings of the modern parliamentary system. He was by far the most educated of all English kings, a true philosopher who could read, write, and speak Latin. Moreover, he was an accomplished musician, composer, and author.

So let's say it out loud, all together.

HENRY VIII WAS THE BIGGEST JERK WHO EVER SAT ON THE ENGLISH THRONE. HE WAS A BRUTAL DESPOTIC TYRANT WITH ABSOLUTELY NO REDEEMING QUALITIES AND WAS A BIG FAT SLOB WHO JUMPED FROM WIFE TO WIFE, CHOPPING THEIR HEADS OFF WHEN THEY DISPLEASED HIM, AND ENDED UP DYING A VAST WOBBLING MOUND OF LARD.

Of course, Henry only chopped off the head of two of his wives. But in doing so he also chopped off the heads of sundry friends, family, and officials. He also thought nothing about torturing people (sorry, that's "using enhanced interrogation techniques") and burning them at the stake. Among those who incurred the King's displeasure was a wife's brother, a wife of a wife's brother, some cardinals, priests, governmental advisors, a lady preacher, various barons, and a lot of ordinary subjects.

Henry was able to accomplish all this with a neat trick. If someone hadn't committed a crime, then he could make them have committed a crime. This was done by getting Parliament to pass what was called a bill of attainder. A bill of attainder was a law that accused a person of a crime and convicted him without the unnecessary irritation of a trial. The nice thing about bills of attainder (from Henry's perspective) is the crimes could be ex post facto. That is, the crime didn't have to be a crime at the time it was committed. It was, in fact, the great popularity of bills of attainders with English kings that prompted America's Founding Father to specifically prohibit them (along with ex post facto laws) in the US Constitution.

Even better (again for Henry) was that the rights of the attaindee was forfeit to the crown. In other words, all the accused's property and money was turned over to Henry. It's not cheap being a tyrant.

But there's one more odd thing about Henry, and that's how he is practically a minor character in his own biography. Instead it's his three Catherines, two Annes, and one Jane we read about. Henry's six wives so dominate his life's story that you can practically leave him out and still learn a lot about him. One of the earliest (and still one of the best) mini-series on television was a 1970 BBC dramatization called the Six Wives of Henry VIII. The series was well-received and recently the BBC reborrowed the title for a new documentary, just as did ...

Well, never mind. We'll just start off with Wife #1.

Catherine of Aragon and the "Kynges Great Matter"

Henry meets Catherine

First, we need to realize Henry was never meant to be the worst king of England. In fact, he wasn't meant to be king, period. That singular honor was supposed to go to Henry's older brother, Arthur. And if Arthur was going to be king, he needed a queen.

You see, during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries the countries in Europe fought all the time. France and England were always going after each other, partly because the king of England was still claiming to be the King of France. But fighting too much was quite a drain on the country's coffers, and the money could be far better spent on things like jousts, banquets, hunting, and giving presents to your mistresses. So to make sure England was not fighting more than two or three countries at a time, the king needed to forge international harmony with the countries he didn't want to fight. And what better way to stave off conflict than to have the daughter of one king marry the son of another?

Now the more thoughtful scholar might think that in-laws with armies and navies at their beck and call would be anything but a prescription for peace and harmony. Certainly history has taught us that such cozy family relationships haven't helped the cause of world peace. After all, during World War I the two principle antagonists, Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany and George V of England, were uncle and nephew.

But in 1489, everyone was still testing the theory out, and Arthur's dad, Henry VII, struck a deal with the King and Queen of Spain, Ferdinand and Isabella. Yes, this was the Ferdinand and Isabella who later hired Christopher Columbus and set up the Spanish Inquisition. Nominally Spain was two countries, Aragon and Castile, while the southern part of the peninsula was still controlled by the Arabs. So the marriage of Ferdinand (of Aragon) to Isabella (of Castile) had united the two northern provinces, and the two sovereigns ruled the country as co-equals.

The final deal, then, was that Arthur, Henry VII's oldest, would marry Ferdinand and Isabella's daughter, Catherine. Catherine, officially styled "Catherine of Aragon", was one of the youngest children of the Spanish couple and would be of most value to her parents if she could get married off to some foreign prince. Still, arranging the marriage with Arthur was really planning ahead since at that time Arthur was two and Catherine was three. But the plan seemed to work, and while the couple was growing up, England and Spain kept the peace. Catherine and Arthur were finally married on November 14, 1501. By then, Arthur was fifteen and Catherine sixteen.

The trouble was Arthur died the following April. That elevated Henry, Jr. - our Henry - as heir to the throne. For the nonce, though, Henry, Sr. decided the best thing was to keep the deal with Spain that Catherine would be the next Queen of England. So the young Henry and Catherine were "betrothed". But as Henry was only eleven, the couple's actual marriage could wait.

Now in that day and age the wife's family was expected to pay the husband to marry their daughter. Such a payment - called the dowry - was expected because the husband would have extra expenses in supporting a wife while the father of the bride would have one less teenager in the home and so would be in considerable financial relief. The custom of the dowry, which seems quaint by today's standards, still exists in that sweetie-pie has daddy shuck out the coin of the realm (no joke intended) to pay for her wedding. But whatever the origin of the custom, Ferdinand agreed to pay a hefty sum for his daughter's marriage. So once Arthur and Catherine were married, Henry, Sr., sat back and waited for his dough.

We don't know if there was a hard and fast payment schedule, but it seems that Ferdinand was quite the deadbeat. Complicating matters was that Isabella had died in 1504, and since she was the official ruler of Castile, Ferdinand's control over the whole of Spain was now shaky. Matters were further complicated since in 1492, the Arabs had been kicked out across Gibraltar and back to Africa. So Ferdinand now had to worry about the south of Spain as well. Money slated for Catherine's dowry would be far better spent on things like paying soldiers, casting bronze into cannons, and bribing officials. But Henry, Sr., said sorry, no money, no wedding, and the nuptial plans for Catherine and Henry were shelved.

Strangely, Ferdinand left his daughter in England. Henry Sr. continued to grant Catherine's living expenses, but he did so most grudgingly, seeming to hint that anything he gave her was a loan. Certainly, Catherine kept writing to her dad saying she was broke and wanted to come home. But Ferdinand seems to have done little or nothing. He either didn't give dos trozos de mierda about his daughter, or he just figured things would eventually work themselves out.

Well, it turns out they did. In 1509 Henry, Sr., died, and Henry VIII came to the throne. Henry, now nearly eighteen, immediately married Catherine, and her problems were over - at least for a while.

Catherine had to live on charity.

It seems that the marriage really was a love match, but everyone knew its actual purpose was to make another King of England. So Henry and Catherine both got busy, but only their fifth child - a daughter - survived. She was named Mary, and in addition to becoming one of the most reviled of English queens, has suffered the indignity of being equated with a popular cocktail.

But after fifteen wearying years of trying to crank out a male heir, Henry was getting tired. He had been doing his royal duty, but Catherine was clearly falling down on hers. By 1525, they had their daughter, but no sons. Catherine was now forty - quite mature for a Renaissance woman - and Henry doubted that she would ever produce a king. In fact, in the remaining nine years of their marriage, Catherine never conceived again.

Catherine's apparent lack of fecundity may not have been entirely her fault, of course. By 1515, that is the sixth year of their marriage, Henry had begun fiddling around with some of Catherine's attendants, most notably a Miss Elizabeth Blount. Elizabeth even had a son that Henry acknowledged as his own. Henry thought briefly about making the young Henry Fitzroy (as the child was called) the crown prince, but he finally just set him up as the Duke of Richmond. That was in 1519, but by then another lady had captured the King's attention. That was Mary, the daughter of a well placed diplomat and court official, Sir Thomas Boleyn. Yes, that's Mary Boleyn. Don't get ahead of the story.

Now Henry prided himself on his religious knowledge and piety and realized that the gender of a couple's offspring - that is, a completely natural and randomly occurring phenomena - was a message from God. In this case, it was absolutely clear (at least to Henry) that God didn't think Henry and Catherine should ever have gotten married. The only way to have a male heir, then, was to enter into a marriage that God did approve of. Unfortunately, the Catholic Church did not (and does not) permit divorce. "'Til death do we part" was taken quite literally. So what to do?

In canon law there were (and are) certain ecclesiastical "impediments" to a marriage. If a couple wants to marry, but there is an impediment, then the marriage cannot take place. But as sometimes happens, an occasional marriage with an impediment can unwittingly slip through.

Now if such an improper marriage occurs, it may be possible that the union can be annulled - that is, ruled to have been invalid from the start. Each case, though, has to be examined carefully because, as logicians say, an impediment is a necessary condition, but not a sufficient condition for annulment. But still, if Henry wanted an annulment, he needed an impediment.

It will come as no surprise that once Henry went looking about for an impediment, - surprise! surprise! - he found one. There in Leviticus 20:21, the Bible expressly forbade a man to marry his brother's wife. Worse and worse, the passage also said that if brother and sister-in-law did marry, they would be childless.

Of course, Henry and Catherine weren't childless, and another passage - Deuteronomy 25:5 - said a brother must wed a his brother's wife if she was widowed and the marriage had been childless. That described Catherine perfectly. So according to the Bible Henry had to marry Catherine.

But Henry decided that he and Catherine having no son was close enough to their marriage being childless, and besides, he figured God didn't really mean that Deuteronomy stuff, anyway. Yep, God was angry about their marriage, no doubt about it. So lest he make God even angrier and now armed with the impediment, Henry decided it was time to go to the Pope for an annulment.

Unfortunately, canon law also stipulates that if there is an impediment to a marriage, then the couple might still be able to marry provided they are granted a dispensation. If a dispensation is granted, the marriage can go ahead and be valid despite the original impediment.

Back in 1509, the Pope had been Julius II. Julius, we learn, already knew about that Leviticus stuff, and after Arthur died, he had officially given the needed dispensation allowing Henry and Catherine to marry. In other words, Leviticus or no Leviticus, there were extenuating circumstances that made it OK for Henry and Catherine to marry. In this case, the marriage promoted peace and harmony between the two countries, and such a benefit trumped a piddly-ant Biblical prohibition.

But now Henry was asking the current Pope, Clement VII, to overrule a previous Papal dispensation - and a dispensation that Henry himself had wanted! Even though popes weren't universally regarded as infallible until 1870, most people, particularly popes, thought they were infallible enough. Would, then, Clement reverse Julius's ruling and annul the marriage?

Actually, there were good reasons to hope he would, particularly if the annulment involved Catherine. In 1527, Clement had been held under siege by troops led by none other than Catherine's uncle, Charles V, the (now) King of Spain (Ferdinand had died in 1516). True, Charles had expressed regret that his troops had ransacked the Holy City and killed perhaps 30,000 inhabitants, but Clement didn't really think Charles meant it. It certainly would have have taken but little arm twisting to get Clement to rule against the Spanish royal family. But requesting an annulment was still a touchy subject. So how should the argument best be put to the Pope?

Now enters one of Henry's advisors, Thomas Wolsey. Thomas had been Archbishop of York since 1514, and the next year Henry had appointed him Chancellor which was the King's right hand man. Thomas had a lot in common with Henry, not the least of was he liked to eat too much, entertain the ladies, and interpret the Bible so that his private personal biases, politics, and wishes were always the same as God's will. Thomas was probably Henry's most loyal subject, and he had one of the best legal minds in England.

He was certainly Henry's hardest working minister. We even have a first hand account left by a secretary, George Cavendish, on how industrious Thomas was. Thomas, George wrote, "roose earely in the mornyng abought third jor of the clock, syttyng down to wright letters all which season my lorde neuer roose oons to pis". In the records, though, Thomas comes off as a bit of a grump, which isn't surprising considering his chief clerk couldn't spell and was vulgar.

Thomas neur roose ons.

As Chancellor, Thomas was naturally heavily involved in Henry's dealings with the Pope, and as an archbishop he was well versed to argue religious matters. However, in this case, he had found a legal argument which made a strong, even ironclad, case to reverse Julius's dispensation.

What Thomas had discovered was that when Julius had issued his dispensation, the Pope had not properly addressed whether Arthur had completely fulfilled his marriage "debt" (wink, wink) to Catherine. Now unless a marriage is consummated - which completes payment of the (snicker) "debt" - it was not really considered a done deal (consummatus in Latin, in fact, means "completed"). So unless Julius could confirm that Arthur had made his deposit, he couldn't even claim the young king and Catherine had been married in the first place.

And sure enough, in his dispensation Julius had indeed skimmed over the subject. His dispensation simply said the marriage was "presumably consummated" (forsan consummatum). Julius, like most popes of the era, was no stranger to keeping company with the ladies, and he figured that as Catherine and Arthur had been married nearly five months, surely something must have happened on those long cold nights in the castle. But Julius had not, Thomas pointed out, really established that the consummation had taken place. So the dispensation was not properly drafted.

Logically this seems a strange argument for Thomas to use. Couldn't someone just say, well, if Arthur and Catherine weren't really married, why the heck did Henry and Catherine even need a dispensation? Well, the answer is they wouldn't if - and it's a big IF - Catherine's marriage with Arthur had not been consummated. In that case, there would be no de facto previous marriage, and Henry and Catherine could marry. But the point Thomas was making was that Julius had waffled on that crucial point. Therefore, the dispensation was invalid on legal technicalities alone, and without a proper dispensation, Henry and Catherine were not legally married.

So Wolsey happily told Henry that all they had to do was simply go to Clement, point out that Julius had failed to properly draft the dispensation, and the King's marriage would be void. It didn't matter what the Bible said about brothers and sisters-in-law or whether there was any wham-bam-thank-you-ma'am in the five months Arthur and Catherine were together.

Henry, though, didn't like the idea. He believed that regardless of legal niceties, the case should be judged on the fundamental scriptural prohibition in Leviticus. No pope, Henry felt, could issue a dispensation for a man marrying his brother's wife. The Bible said it was forbidden, and that was that.

Unfortunately, Henry also now proved the old adage about the client who acts as his own attorney. He decided that he wouldn't let Thomas carry the arguments to Rome. Instead, he, Henry, would write up and send off the arguments himself.

That was a big mistake. Clement may very well have sided with Henry because Julius had messed up on a legal technicality, particularly if the issue was pointed out quietly by a lowly archbishop. But to have an English king directly dictate what a pope could and could not dispense on Biblical grounds was something else again.

Clement was diplomatic, though. He said he would not rule on such a touchy issue without a formal investigation. He immediately dispatched Cardinal Lorenzo Campeggio to England with instructions to set up a formal hearing. And if some historians are to be believed, Clement also instructed Lorenzo to rule against Henry.

Henry had yet one more obstacle. That was Catherine. A tiny girl, but feisty, she was also quite knowledgeable about Catholic doctrine and wasn't about to give up being queen without a fight. Catherine had her own trump card to play, and she wasn't going to argue about any technical faux pas in Julius's dispensation.

You'll remember that we said that if Arthur had not paid his marriage "debt" to Catherine, the marriage was not complete, and in that case, she never would have been Henry's sister-in-law in the first place. No dispensation would be needed, and she would be free to marry Henry - that is if the marriage with Arthur had not been consummated.

And that, sirs and madams, is exactly what Catherine claimed. Nothing, she staunchly maintained, had happened with Arthur during those long cold nights in the castle. In their five months together, she and Arthur had been polite to each other but nothing more. So by canon law, she had never been married to Arthur. On the other hand, her marriage with Henry had clearly been consummated and with vigor. So her marriage to Henry was valid and indissoluble.

In a dramatic scene, Catherine appeared at the hearing and threw herself at Henry's feet (Shakespeare's version is actually pretty close to the mark). Although Henry bade her courteously to rise, Catherine remained kneeling and declared "And whan ye had me at the ffirst (I take god to be my Iuge) I was a true mayed wtowt touche of man, and whether it be true or no, I put it to yor concyence." Obviously, English was not Catherine's first language. But in any case, Henry had no "concyence" and just sat there like a jerk.

After Catherine rose and left the room, Henry sat back and waited for Lorenzo to rule in his favor. But Lorenzo abruptly adjourned the court, saying the matter was too complex for him to decide, and he had to check with higher authority. Well, since the King of England was sitting right there, it was clear who the other higher authority would be. So Henry and his "Great Matter" was left hanging.

Like many a good business executive, Henry now decided if something went wrong, it was someone else's fault. That he, Henry, might have screwed up never entered his mind. Instead he began to suspect that Thomas and Lorenzo were both on Catherine's side and were in active cahoots with the Pope.

That was certainly not true. Thomas, far from being against the king, had been furiously working to keep the hearing in England. That way Henry would get the decision he wanted, and if Lorenzo was presiding, the annulment would then have official, although unwitting, sanction of the Pope. But since Lorenzo had now deferred the decision to Rome, a favorable ruling (for Henry) was far less likely. Clement did in fact rule that Julius's original dispensation stood, and Catherine and Henry had been and were legally married. For now, at least, Catherine had won.

Thomas's lack of effectiveness on Henry's behalf had one particularly unfortunate side effect besides ticking Henry off. What was almost as bad (at least for Thomas) is the court and even the country were now split into into pro- and anti-Wolsey factions.

The pro-Wolsey crowd were people who liked Catherine, and they included a good chunk of the ladies of the court, the ladies' boyfriends, and a lot of ordinary English people. The anti-Wolseyites were those who sided with Henry and were largely composed of his flunkies, sycophants, personal attendants, and [boot] lickers. Among the anti-Wolseys was Sir Henry Norris, the King's "Groom of the Stool". Sir Henry (and we'll hear more of him later) and many others of the King's intimates - and you can't get more intimate than the Groom of the Stool - began to whisper that Thomas was not just a bumbling ecclesiastical and legal nincompoop, but that he was a traitor to the crown as well.

The Groom of the Stool

The Amicable Grant

The Amicable Grant

One part of Henry's reign we haven't talked much about was his dealings with France. Henry was King of England, but he thought England should also be most of France as well.

You see, at one time it was hard to tell who was the King of France and the King of England. For instance let's go back to about 1150 and to another Henry - Henry II. Henry II was King of England and Lord of Ireland and Wales, yes. But he was also the Count of Anjou, Duke of Gascony, Duke of Aquitaine, Duke of Normandy, and Count of Nantes. These were all provinces located across The Channel in what is now modern France.

The problem, though, is that although Henry was the King of England, he was was not the king of his land in France. Strictly speaking the French provinces still belonged to the King of France, first Louis VI and then his son Phillip II. So Henry was subordinate to the King of France for his lands on the Continent. On the other hand, the King of France had no control or claim to England. So there Henry ruled supreme.

This continued under Henry's son, Richard the Lionhearted. But when Richard died in 1199 (being killed during a siege at Chalus, about 250 miles south-southeast of Paris), his younger brother inherited his lands and soon lost everything in France to Phillip. After that the Kings of England were the Kings of England.

But then in 1347, King Edward III decided to reassert England's Gallic claim and sent troops over to Calais. This is just across the Channel from Dover and when people swim the English Channel they usually go from Dover to Calais. Edward though sent everyone over in boats. He set siege to the town and eventually took it over.

So that's the way things were when Henry - that is, our Henry, Henry VIII - came to power. Calais remained in English control but that had been about all England could grab. But Henry now thought that England could use the town as a base for a new invasion to take all of western France back.

Well, he didn't have much luck. With the approbation of the king of Spain, he sent some ships across the channel and sent his troops into France. The issues of the war are complex, but suffice it to say eventually Henry had to pull back to England and make peace with France.

So in 1520, Henry met with Francis I at a get-together called the Field of the Cloth of Gold. Naturally this wasn't too far from Calais. The meeting was one big party where everyone had a good time with jousts, banquets, and entertainments. The party lasted a bit more than two weeks and everybody then went back home. On parting, Henry and Louis swore their eternal friendship.

They didn't mean it, of course. And in 1525, Henry decided to have a crack at France again. The only trouble was money.

You see, waging war isn't cheap, and this was a day when money meant hard cash. None of that borrowing on the deficit stuff. If you had soldiers, you literally had to pay them with coin of the realm.

The trouble was the last wars - not to mention Henry's banquets, parties, jousts, hunting trips, and just fancy living - had spent more than his taxes were taking in. Henry needed more money if he wanted to get back the lands in France that (he thought) were his rightful due.

Well, there was nothing to do but go to the English people and ask them for the cash. So Henry had Thomas Wolsey send out messengers to collect what was called an "amicable grant". The messengers would ride into town and ask the English citizens to fork over six percent of their income for a year. The clergy would have to turn over one-third of their income. Sitting back with a smile, Henry waited for his dough.

Neither Henry nor Thomas expected the messengers to return empty handed - and some rather bruised and battered. It seems that Henry's request had gone down like the proverbial lead balloon.

In fact, when the messengers arrived at the towns, the people had been downright nasty. They pointed out that they had already funded Henry's earlier wars, and England had not gained one additional foot of French soil. Worse, the money for the previous wars, like this grant, were supposed to be loans. And none of them had been repaid.

Worse, suppose this new war was successful. They would then have to pay even more money for the upkeep of the occupying forces. They would have to be the gift that keeps on giving.

Another point was not lost on some of the more well-read citizens, They pointed out that all loans, grants, and taxes were supposed to be approved by Parliament. But this amicable grant had just been an order from Thomas Wolsey. So even it's legality was questionable.

In the end virtually no money was collected and in a number of towns riots broke out. Although Henry sent in troops to quell the disturbances, the discontent was so widespread Henry had to tell the troops to tread lightly. Deal with the people gently, he said, restore order, and then pull out.

At this point, we see Henry did indeed have the makings of our modern elected officials. If anything bad happens, it isn't his fault. Amicable grant? What amicable grant? Why, he, Henry said, hadn't known anything about it. Thomas must have issued the order on his own authority. Yes, it was Thomas that caused all the trouble.

Anne Boleyn: Henry's Hottie

Anne was a flirt.

By the late 1520's, the most influential member of the "Out-With-Wolsey" crowd was the king's new girlfriend, a somewhat average looking attendant of Catherine's named Anne Boleyn. Yes, that's Anne Boleyn. We know we earlier said Mary but now we're talking about Anne.

Although the Bible said a man should not marry his brother's wife, it also says (among other things) that thou shalt not kill, thou shalt not commit adultery, and thou shalt not covet thy neighbor's ass. Breaking the first two commandments never bothered Henry, and there were certainly many a neighbor's ass he coveted. With Mary, the eldest of the Boleyn children, Henry had long gone beyond coveting. But soon and perhaps because Mary was so easy, the King had switched the object of his coveting to the cute backside of Mary's sister, Anne.

But Anne, despite the epithets thrown at her later, was quite the proper lady. Either that or she was playing hard to get. Once Henry started making his overtures, Anne pointed out that Henry was still married to Catherine. As an honorable lady of the court and an attendant of Catherine, Anne said she could never do anything disloyal to the Queen (we don't know if Anne mentioned Henry had also been bonking her sister). Henry then asked if Anne would be his "official" mistress? Well, if that just meant she could be devoted to her King and give him her unswerving loyalty, that would be fine. But as long as Henry was married to someone else, all he could do was covet.

Coveting was not enough for Henry, and he began laying the ground work for Anne becoming Queen #2. First, he went to Catherine and said regardless of what the Pope said, he could not in good conscience continue to live with her in violation of scripture. Oh, he would still provide for her, of course, with castles, servants, and an income. She would even have a royal title, the rather unflattering sounding "Dowager Princess of Wales". But she had to give up her queenship and all that went with it. That included her jewels which Henry then passed on to Anne.

Now with Catherine out of the way, Henry decided he could now spend more time with Anne. The two started going to jousts and hunts and having dinner together. But Anne still said no soap to anything more until they were married.

Soon, though, there developed another little glitch. Rumors were circulating that Anne had been secretly betrothed to a young friend of the Boleyn family named Henry Percy. In that day and age, a betrothal had some force of a binding contract and had to be properly dissolved before either of the couple could marry someone else.

Thomas Wolsey summoned the young man and yelled at him that the "secret" betrothal was unsuitable for a young man of his standing. Custom demanded, blustered Thomas, that Percy get permission to marry from both his father and the King. Percy had done neither. This drumming down - which was done publicly - left Percy quite abashed. He asked pardon and agreed to marry a lady named Mary Talbot, who it turned out couldn't stand him.

Actually the source material is contradictory as to the real relation of Anne and Percy. But regardless of her past, Anne now clearly wanted to marry Henry. But she still insisted if Henry wanted to go beyond mutual admiration, then they had to be man and wife. Henry said OK, and he pledged he wouldn't even fiddle around before they got hitched.

But a horny king is not a happy king, and Thomas's inability to get Catherine legally out of the way was getting on Henry's nerves. By the time 1530 rolled around, Catherine was still Queen, Thomas was still Chancellor, and Anne was pretty much fed up with the whole silly mess.

In early November 1530, Anne and Henry sat down to dinner in the king's privy chamber. "Privy" means private, not "privy" in the more modern - or at least Victorian sense. That would not only have been most unsuitable for a romantic candlelight dinner but downright disgusting as well. Of course, a "private" dinner for a king also included ten or twenty waiters. So what Henry and Anne said was duly recorded by a servant who was probably looking for a book deal.

Anne was in a grumpy mood and started ragging about Thomas. "Besides all that what thynges hathe he wrought within this realme to yor great slaunder and dishonor," she huffed, "there is neuer an noble man within this realme that if he had don but half so myche as he hathe don, but he ware well worthy to lease his hed". "Whye than," said Henry, speaking so Anne could understand him. "I perceive ye are not the Cardynalles frend." That was the understatement of the year.

Anne and Henry in the Privy Chamber

The next day Henry was once more meeting with Thomas about the thorny problem of Catherine when Anne sent him a note that she wanted to go hunting. Henry abruptly ended the meeting and went off to be with his sweetie. It was clear now that Anne had the King by his Crown Jewels. You can also bet Anne returned to the topic of the "Cardynalle" since Henry never saw Thomas again. In a few days he replaced him as Chancellor with Sir Thomas More.

Now when we say Anne was average looking, that doesn't mean she was a Tudor version of Maggie Jiggs. She simply was not a classic beauty by the standards of the age. Her neck was too long, we hear, her complexion too dark, her mouth too wide, and her bosom too slight.

But we have to be honest and say it was Anne's detractors that emphasized her imperfections, and Anne's plainness seemed to have grown worse with the telling. Nicholas Sanders, writing in the late 1500's and scarcely a contemporary (he was six when Anne died), even said Anne had a large "wen" on her neck - although no one knows whether he meant a true subcutaneous cyst or benign tumor, a large mole, or just an unusually prominent Adam's apple (women, by the way, do have Adam's apples, but they are normally not as pronounced as in men). Nicholas said the "wen" was so unsightly that Anne had to wear high collars to cover it up. He also said she had an oval face, a jaundiced "sallow" complexion, snaggle teeth, and on one of her hands - get this - six fingers.

On the other hand, George Wyatt, whose grandfather, another Thomas, was a member of Henry's court, wrote that Anne was quite pretty. He didn't mention any wens or extra digits, but did say Anne had "upon the side of one of her fingers, some little show of a nail" (possibly a split or double nail), and also that "there were said to be upon some parts of her body certain small moles incident to the clearest complexions." Of course, we have to be careful that George was being too nice since he was extolling the memory of Anne as a gracious lady and a proper queen. But we have to emphasize that no one - that's no one - who knew Anne personally, whether friend or foe, mentioned anything about her extra fingers, double nails, moles, wens, or crooked choppers.

What we do know is that despite any shortcomings of her neck, complexion, teeth, fingers, or bosom, Anne was - to use today's patois - "hot". Her most distinguishing characteristics were extremely lustrous purplish black hair and dark liquid eyes which - as contemporaries noted - she used with great effect. In any case, as any honest man with a functioning endocrine system will testify, a hot babe does not have to be a raving beauty. Whatever it was, Anne had something that made men slobber.

Unfortunately, the new Chancellor, Sir Thomas More, was no more effective than Cardinal Wolsey in resolving the "Great Matter" about Catherine. The Pope still wouldn't budge and neither would Catherine. Things were at an impasse, and the King, still keeping to his vow to abstain, was getting quite foul tempered. Finally a solution dawned on him.

Just why, he wondered, should anyone from Italy, whether prince, pauper, or pope, tell him, the divinely ordained king of England, what to do? And in his own realm at that? England was his country, by Heaven, and he could do what he wanted.

So starting in 1531, Henry went to Parliament and had them start passing a number of laws that made him the Supreme Big Stud of Everything in England. The first law passed was the Statute of Praemunire (pronounced pry-mun-EYE-ray). This forbade any "cleric" of the Church in England to appeal any ruling of the king to Rome. That took care of Lorenzo going to the Pope.

Naturally, not everyone was happy with the new law. Although Sir Thomas More, Henry's new chancellor, agreed the King could now marry Anne, but he was concerned about Henry's claim of veto power over all church matters. Sir Thomas had always held the traditional view that the King was supreme in temporal matters, but in divine matters the Pope trumped everyone. So the next year, Sir Thomas resigned the chancellorship, much to Henry's chagrin.

In that day, an official was supposed to serve, as they say, at the King's pleasure, that is, as long as the King wanted. Resignation was practically an act of disloyalty. Then in 1534, Henry had Parliament pass a new law, The Act of Supremacy which required all subjects to take an oath acknowledging that Henry was in charge of the English church. Sir Thomas refused and was arrested.

We need to pause a minute here and talk a bit more about Sir Thomas. If there is anyone who has become elevated as the most high minded of Henry's advisors, it is Sir Thomas More. All who have watched the film A Man for All Seasons know, Sir Thomas was beheaded because he refused to acknowledge that Henry was head of the Church in England. We also learn that a real jackass, Sir Richard Rich, committed perjury at Sir Thomas's trial.

The story that Sir Richard committed perjury comes from an actual contemporary of Sir Thomas, Sir Henry Roper, who wrote Thomas's first biography. However, Sir Henry was not entirely objective, and he wrote the book as a bit of a self-imposed penance for having flirted with Lutheranism. Sir Henry was also, we should add, the husband of Sir Thomas's daughter, Meg.

Furthermore, Roper's account of the testimony does not jibe with other truly contemporaneous records. These show that Sir Richard did indeed repeat a conversation he had with Thomas More. And yes, Sir Richard said Thomas did discuss that the king could not be head of the church. But Richard did not commit perjury, and Sir Thomas, despite Paul Scofield's spittle flinging but noble diatribe in the movie or the long-winded indignant quote given in Roper's biography, never said he did.

Instead, what Richard related was a conversation when he and Sir Thomas were discussing legal scenarios about the new law. Sir Thomas's argument against Henry's supreme sovereignty was therefore a lawyerly discussion, and this was made clear at the trial. But the court, knowing it had Henry to deal with, decided to use the statement as Sir Thomas's true opinion, and after the (guilty) verdict, Sir Thomas acknowledged that it was. So if you go by the rule of law, the court came to the correct conclusion, although it seems a bit severe that they decided to cut Sir Thomas's head off.

Thomas was widely admired for his courage, and soon after his death, a number of his supporters began to wonder why he, a martyr to truth, justice, and the English way, wasn't a saint. The man died for his principles, for crying out loud! And yet look at a guy like Thomas Aquinas. Why he mostly sat around on his roseo culo just writing books. And yet Aquinas was a saint, and Sir Thomas wasn't!

Sainthood, though, is normally not an initiative taken by upper church echelons. It usually starts from the grassroots, and it wasn't until the early 20th century that the diocese of Southwark in London seriously took on the job of making Sir Thomas a saint.

Now one of the stickiest points in getting someone canonized is that you're supposed to have a miracle or two. The miracles don't have to be very ostentatious, mind you. You don't need to turn water to wine or make a blind man see. Still, after 500 years no one had reported any miracles for Thomas. This was a problem since it would have been just a wee bit too much of a coincidence if all of a sudden someone reported they had received a miraculous cure via Sir Thomas's intervention just when people began pushing for his sainthood.

Well, it seems the lack of a miracle was taken care of easily enough and in a very modern manner. Thomas's supporters turned the problem over to a committee. In this case, the committee was a special consistory, that is, an advisory meeting of the College of Cardinals. The consistory decided that, as nice as a miracle is, you don't really need one for someone to be a saint, or at least not for someone like Sir Thomas More. So that took care of that, and in 1935, Sir Thomas was duly canonized.

Sir Thomas has had his detractors, of course. The earliest member of the Let's Trash Thomas Club was Robert Foxe, a near contemporary who went into spittle flinging diatribes about Sir Thomas and claimed (among other things) that during Sir Thomas's tenure as Chancellor there were horrific executions (including burning at the stake) for crimes that were no worse than reading William Tyndale's English translation of the Bible. So why, Robert wondered, should Sir Thomas be looked on as a defender of freedom of conscience and yet everyone thought King Henry was a jerk? Well, for now we won't butt into a centuries old argument except to say such are the quirky judgements of history, and once you have a highly fictionalized film biography to help mold public opinion, no further discussion is needed.

But for Henry, the immediate problem had been resolved. Henry and Anne were finally married in January 1533. But to let things simmer down, the ceremony was held in secret.

As you can imagine, Clement was not pleased that Henry now claimed he had a more infallible infallibility than the popes. So out of the Vatican came a Papal "bull" - for some reason that's what the Pope called a document - that officially excommunicated Henry. Excommunication meant Henry could no longer go to church and receive communion. Now you might think since Henry could now sleep in with Anne on Sunday mornings, that would be fine. But back then excommunication was a real black mark and was one of the most powerful tools of persuasion the Pope could wield. The effect was so strong that an excommunicated king would generally work out some deal with the pope and have the ban lifted.

But as far as Henry was concerned, the pope's bulls were just that. He was head of the Church in England, and he would do whatever he felt like. He kept going to mass, and finally it was officially announced that Henry and Anne were married. Now everyone knew England had a new queen.

Henry thought the Pope's bull was just that.

Today everyone sees that when Henry proclaimed his supremacy over religious matters that he became the founder of the Church of England and had joined the now popular Protestant Reformation. But actually Henry didn't think he founded anything. As far as he was concerned, neither the Statute of Praemunire nor the Act of Supremacy did anything other than affirm what had always been fact. Since the King was God's representative in England, his reign was divinely ordained, and therefore no one was above the king in his own country. If the Pope wanted to run things in Continental Europe, that was fine. But at home in England, it was Henry who was in charge.

The truth is Henry considered himself a good Catholic and absolutely despised the increasingly stylish Protestant Reformation of that upstart Martin Luther. Martin had split with Rome over a lot of things. For one thing, Martin didn't think you should be burned at the stake for reading alternative translations like William's. He also thought that the bread and wine used in communion was just that, bread and wine - blessed bread and wine, yes - but bread and wine nonetheless. The Catholic Church held then (and still does) that upon Elevation at the Mass, the bread and wine of Holy Communion is transformed into the actual body and blood of Christ. Martin said this was superstitious nonsense, and even today you can still get into lively debate on the matter if you get a Lutheran and a Catholic together at Happy Hour.

But - and it's a big but - there were many Protestant sympathizers in England and even quite a few at Henry's court. Among the most important of these reformers - called "evangelicals" - was Henry's new queen. She displayed a copy of William Tyndale's translation of the Bible in (gasp!) English which she urged her ladies to read. She also read the Bible in French, which was also considered heretical behavior. Henry knew about Anne's Protestant leanings, of course, but didn't think it worth troubling about, at least as long as it was Anne.

On the other hand many people in England, particularly in the north, still held the Pope was supreme, and Anne's radical beliefs, plus the sympathy people felt for Catherine, now divided England into strong pro- and anti- Anne factions just as there had been for Wolsey. And a lot of people at home and abroad didn't even regard Anne as the real queen.

One of the worst of Anne's enemies at the English court was Eustace Chapuys, the ambassador of Charles V. Charles, you will remember was Catherine's uncle and so by default was vehemently anti-Anne. Of course, Eustace sided with his boss.

From the start Eustace tried to have nothing to do with Anne at all, even to the point of being rude. Eustace would not meet Anne personally, and he kept sending snooty comments to Charles about Anne, calling her not very nice names. Eventually Charles had to remind Eustace not to let his personal feelings interfere with his job as a diplomat. But Charles didn't really consider Anne to be the real queen either.

Although Henry's, well, "relationship" with Anne lasted at least nine years, their actual marriage was quite short. She was queen for three years compared to Catherine's twenty four. The short duration of the actual marriage tells us she started having problems with Henry much sooner than Catherine.

Anne's problem was (you guessed it) her failure to produce the next King of England. Anne did have kids, yes, but the only one to live was the first. That was a girl named Elizabeth. Henry himself was now over 40 and it seems that he was slowing down although he wouldn't admit that even to himself.

Instead Henry felt that God was once more showing his displeasure at the marriage. But now there was no clear way out. After all, he had been the one to decide he and Catherine weren't really married. He was the one to say it was OK to marry Anne. So to admit error now was to admit the now infallible King could be fallible.

Well, after a little (a very little) thought, Henry finally figured it out. He had been "bewitched" when he fell for Anne and was a victim of sorcery. And the bewitcher? Well, that could only have been Anne herself. Immediate action was called for to get Henry unbewitched. But since he was king, Henry needed to do everything by the rule of law. So he asked his new Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal, Thomas Cromwell, to start checking into Anne's background.

Although Thomas didn't find that Anne practiced sorcery or was a member of a witches' coven, he did learn that she was a quite a flirt. She liked to toss around all sorts of enticing remarks to the men at the court. She even made some coy comments to Mark Smeaton, who was one of the court's musicians. That was pretty bad. Queens weren't supposed to flirt with - in Anne's own words - an "inferior". Of course, Anne only meant her remarks to be playful teasings, but some people in Henry's court, like Thomas, had no sense of humor.

After using tor ..., sorry, "enhanced interrogation techniques" on Mark, Thomas had all the evidence he needed. Anne was convicted of treason, adultery, and - on the evidence of her sister-in-law - "cohabiting" with her brother George. Today, no historians believe any of the charges. Still, Anne was sent to the Tower of London where she would sometimes break out into fits of uncontrollable laughter even though there really wasn't really much to laugh about.

Four other of Anne's supposed paramours were also arrested. Sir Thomas Wyatt (George's grandfather), Sir Francis Weston, William Brereton, and - get this - Henry's own "Groom of the Stool", Sir Henry Norris. Sir Thomas was soon released, but the rest of the men were beheaded on May 17, 1536. So among other inconveniences arising from the sorry affair, Henry now needed to find someone new to wipe his rear end.

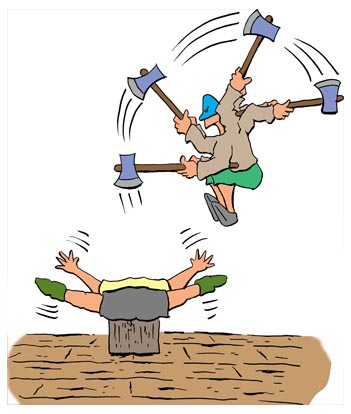

Anne went to the block two days later. Out of "kindness", Henry had imported a swordsman from France, who according to one story distracted Anne by pretending not to know where his sword was. On the scaffold, Anne made a short speech saying about the King that "a gentler nor a more mercyfull prince was there neuer, and to me he was euer a good, a gentle, & soueraigne lorde." Actually Henry was neither merciful, good, nor gentle. He had already become the biggest jerk in English history - and he had just barely gotten started.

He distracted Anne.

Oh, yes. You may read on The Fount of All Knowledge that the name of Anne's executioner was Jean Rombaud. Alas, no primary sources mention his name. Instead, the gentleman's moniker seems to have arisen from a work of fiction written after the turn of the millenium (the most recent millenium, that is). Confusion of fiction and reality is, sad to say, a common affliction in today's world where information is so dominated by motion pictures, television, and the Fount.

Rant, rave, snort.

Jane Seymour and the Pilgrimage of Grace

Henry reminded Jane about Anne.

Of course while all the brouhaha with Anne was going on, you know Henry had picked out his next queen. That was a lady named Jane Seymour, who had been one of Anne's attendants. Jane, like Anne, had rebuffed Henry's approaches and said they couldn't be intimate unless they were married. So on May 30, 1536 only eleven days after Anne's death, they were, and Jane became Queen.

Unlike Anne, Jane was a staunch Catholic, even more so than Henry. In fact, she believed Henry's first marriage with Catherine had been quite legitimate. So in principle she couldn't have married Henry while Catherine was alive. But by the time Jane and Henry were married, Catherine had died, probably of cancer.

Jane was cut more in the mold of the proper Tudor lady than either Catherine or Anne. She was also quite softhearted and was always kind to Henry's children by his previous wives. She even asked him to put Catherine's daughter, Mary, back into the line of succession.

Henry was flabbergasted and not a little irritated by his new bride's effrontery. To acknowledge Mary as his heir would imply he accepted that Catherine really had been a legitimate queen. While he, who was not only the king but also the head of the Church in England, had already ruled she was not. So Henry, figuring that Jane had gotten all her staff to agree with her, had them all summoned and went into spittle flinging diatribes about how they were conspiring to put a "bastard" on the throne. Of course, there was already a pretty rotten bastard on the throne already, and fortunately, Mary herself didn't press the issue. She declared her mother's marriage to Henry was not valid, and she was not successor to the throne. So everyone was (relatively) happy.

But hands down the biggest doing of Jane's tenure was the somewhat misnamed Pilgrimage of Grace. The Pilgrimage was actually a rebellion, led by a lawyer from Lincolnshire named Robert Aske, and the story is probably the best example of what an actual schmuck the English had for a king.

Actually, the Pilgrimage started out as a minor riot for reasons that were kind of silly. In October 1536, a bunch of people took to the streets in Lincolnshire because they heard that Thomas Cromwell's agents were going to take over the parish churches. There were also rumors that marriage and burials were to be banned and that no one would be permitted to eat white bread, chickens, or geese. The riot, though, was short and contained within the city. Soon the landed gentry tried to take control of the movement, ironically in the hope of stopping the violence and staving off Henry's wrath. Unfortunately the manner of placating their king was not very well thought out.

Instead in what marked the real beginning of the Pilgrimage of Grace, on October 10, 1536, Robert Aske and a group of captains marched into the city of York and took over. There was no violence, and the townspeople gave unswerving support to Robert. From the first Robert maintained they were not in rebellion against the king. They were simply trying to "pair" loyalty to the Crown and asked only that certain problems be addressed. Unfortunately their #1 item on their list of Things-for-Henry-to-Do was for the king to reverse his policy regarding what is now known as the dissolution of the monasteries.

The dissolution of the monasteries had begun a couple of years earlier. To improve efficiency of the religious community, Henry had decided to close all monasteries that took in less than £200 a year. At the same time, Henry also asked Thomas Cromwell to check into stories of rampant corruption in the orders. If monks were behaving, that was all well and good, and they could continue to live as before. On the other hand, corrupt monasteries would be disbanded along with the ones that took in the lower revenues.

Henry was not totally heartless, though. The monks would be put on a salary to do whatever monks did best, like teaching or copying books. But they would no longer live with their brothers as a group. Oh, yes, all land, gold, and other assets of disbanded monasteries would go to Henry.

Well, you can guess Thomas found a lot of corruption. By 1536, Henry had decreed about 300 monasteries would be shut down, and all their money and land would be his. Within a couple of years, Henry, whose lifestyle and war waging had been pushing England to the brink of economic disaster, had increased his wealth several fold. Suddenly he was one of the richest monarchs in Europe. Just one more perk for being so pious.

But as we said, the people in the north still felt strong ties to Rome. Most of the populace, including Robert, wanted to keep the monasteries open and have those that were already closed restored. But they insisted they were not being disloyal and were willing to negotiate.

So on October 27, Robert and two of his friends, Thomas, Lord Darcy and John, Lord Hussey, met with Thomas Howard, Lord Norfolk, who was Henry's designated ambassador. The three men found Norfolk was most agreeable. Certainly, he said, Henry would be happy to restore the monasteries. But since the legislation had already been passed, everyone had to give Henry a little time so he could go back to Parliament and get the laws revoked. Norfolk, though, said he himself was busy trying to keep order here in the north, so it would be best for Robert, Darcy, and Hussey to ride down to Windsor and talk to Henry themselves.

Henry received Robert and his friends with courtesy. After listening to their demands, the King hemmed and hawed and said their wording was too "general". They should go back, and talk with Lord Norfolk some more. If they could come up with some specific items he could address, Henry said, then he might be able to help.

So Robert and the others rode back north, and in December again met with Norfolk. They presented him with twenty-five demands called the "Pontrefact Articles". As before Norfolk listened politely but said, weeeeeeeeellllllllll, Henry would certainly consider their demands, and would probably restore the monasteries. But the King was still really busy, so they needed to be patient. And Norfolk said he was busy too. So Robert and his friends should go back to London and present the articles to Henry. When the meeting was over, it wasn't lost on anyone that nothing had been promised, and officially Robert, Darcy, and Hussey were still in rebellion against the Crown.

Then, to everyone's relief, one of Henry's official heralds stood up and read out that all the rebels were pardoned. Reassured, the three men went back to London where they went to the palace for dinner with Henry, who immediately arrested them all.

The herald announced all rebels would be pardoned.

Robert wasn't beheaded (normally too good for traitors), but was condemned to be hanged, drawn, and quartered. This procedure was to let the condemned hang for a bit, and while still living haul him down, cut out his innards, and then chop him into pieces. Robert petitioned the king for mercy and let him be "full dead" before he was cut up. Henry decided to be a real nice guy, and Robert was simply "hanged in chains". That was certainly a relatively merciful procedure where you could either tie the fellow up in chains and let him dangle indefinitely or you could stuff him in an iron cage and haul him up on a pole. Either way the condemned probably died within a couple of days, and the custom was to leave him up as long as possible. There are records that some people were still on display twenty years after they died.

As far as the other rebels went, that is, the common people living in the north, Henry wrote instructions showing that after all these years he had neither mellowed nor had learned to spell any better. "You shal in any wise cause suche dredfull execution to be doon upon a good nombre of th' inhabitauntes of every towne, village, and hamlet that have offended in this rebellion, as well by hanging of them uppe in trees, as by the quartering of them and the setting of their heddes and quarters in every towne, greate and small, and in al suche other places as they may be a ferefull spectacle to all other herafter that wold practise any like matter whiche we requyre you to doo, without pitie or respect." None of this endeared Henry to his subjects in the north, particularly those who didn't like run-on sentences.

The dissolution of the monasteries continued apace and within a few years, most had been closed down. The buildings themselves were used as sources of building stones and the English countryside rapidly became dotted with the ruins of the abbeys. Even today you can travel through England and see the remains of the monasteries that have been left over from Henry's Dissolution.

And Jane? Early on she had interceded with the rebels and had been one of the first to ask Henry to negotiate. With her, though, Henry showed his true feelings and again went into spittle flinging diatribes, making a not too veiled reminder to Jane about what happened to Anne. Jane took the hint and said no more.

Jane, though, kept Henry's favor mainly because on October 12, 1537 - one day shy of the anniversary of the Pilgrimage of Grace - she had a son who, although was not as robust as Henry had been, was healthy enough. Then a few weeks later, on October 24, 1537, Jane died. But her son, who was named Edward, would indeed one day be King.

Anne of Cleves: Ball Four and You're Out

Henry lykyd Anne not well.

When Henry found himself a widower and with only one prince, he decided an extra son or two wouldn't hurt. So he sent out letters to the courts in Europe. There were, after all, plenty of princesses around. Which of them wouldn't want to be Queen of England?

But the reader may be shocked! shocked! to find out that there were not many young beauties anxious to become Mrs. Henry VIII # 4. In fact, some seemed downright sarcastic when they were asked. Christina of Denmark (who at the time was Duchess Consort of Milan) said if she had two heads she might be able to marry Henry. There was also Marie de Guise, a young widow who was the Duchess of Longueville, who also seemed like a good prospect. After all, she was rather hefty and Henry said he needed a big wife. But Mary said she was a big woman, yes, but she had a very little neck.

The selection of a new queen was made more difficult because few of the wifely candidates showed any interest in making the long difficult trip to England just so Henry could look them over. So Henry sent his official portrait painter, Hans Holbein the Younger, to take the ladies pictures. Although to many modern eyes the subjects of Hans's pictures often look a lot alike, Hans was considered one of the greatest portraitists of the Northern Renaissance. But Henry believed a Holbein portrait was good enough to select his next soulmate. So in some ways Hans created the prototype of the Internet matchmaking service.

One of the portraits Hans brought back was that of the German princess, Anne of Cleves. Since she came from a noble family and from Germany, she was certainly good enough to stand as an English queen. She had also received the enthusiastic accolades of Henry's ambassadors. Better yet, Anne had said yes. So Henry looked at Hans's picture and said, fine, Anne it is.

But when Anne showed up, Henry did not like what he saw. His queen-to-be was even less a classic beauty than her late namesake predecessor. The new Anne was short, dark complected, and (we must say it) a bit dumpy. But a deal was a deal, and Henry and Anne were married on January 6, 1540.

You're probably expecting that Henry would have immediately dispatched Hans to the the Tower and then have his head chopped off. But that didn't happen. Instead, Hans continued to be Henry's portrait painter. So in all likelihood, Hans's portrait is faithful enough and does justice - flattering justice, perhaps - to the lady. But that's the trouble with good portrait artists. Once Isaac Asimov had a portrait drawn for a science fiction magazine and said he was amazed the artist could render his likeness both accurately and handsome. So we shouldn't be surprised that Hans could paint a flattering portrait of a relatively plain looking young lady. Besides, it wasn't Anne's face that Henry took most objection to. After all, there are qualities that a portrait artist can't capture.

Henry quickly found more things not to like about his new bride. After the couple's wedding night, Thomas Cromwell, perhaps with a roguish wink, asked Henry how things went. Henry's reply did not bode well, either for Anne or Thomas. "I lykyd her beffor not well," Henry grumped, "but now I lyke her moche worse." Then he went on to provide somewhat too detailed supplemental information. "I haue felt her belye and her brests and therby as I can judge she sholde be noe mayde which strake me so to the harte when I felt them that I hadde nother will nor corage to precede any further in other matters." In other words, Henry decided a "mayde" should be firm and perky, and so when he found himself alone with a bride who had flab, sag, and body odor, he couldn't lift his lance for the joust.

Henry, though, was wrong to think Anne was not a "mayde." She had led such a sheltered life she didn't even know what newlyweds were suppose to do. Later she was asked what happened on those nights with her husband, and she said she and Henry would retire, the King would give her a good night kiss, and then roll over and go to sleep. In the morning he would rise, give her a quick peck, and leave. She thought that was all that was required for her to fulfill her queenly duty.

This couldn't keep up - no bad joke intended - and after six months, Henry told Anne that he had "reconsidered' their marriage and thought it better that they should part. Being no fool, Anne settled amicably. She was pensioned off and given two estates complete with servants and attendants. For the rest of her not terribly long life, Anne remained on good terms with Henry and his immediate family.

Despite the less than perfect outcome of Henry's latest marriage, Henry seemed to appreciate the efforts of Thomas Cromwell, who had brokered the deal. The King gave Thomas even more offices and responsibilities, and Thomas himself was relieved things had sorted themselves out so painlessly. In addition to being Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal, Chancellor of the Exchequer, the Lord Great Chamberlain, and the Earl of Essex, Thomas was now made the king's chief minister and principal secretary. If ever there was a man sitting pretty in the favor of the king, it was Thomas Cromwell.

Then on Thursday, June 10, 1540, Thomas was sitting happily at work at Westminster Hall when a squad of the Yeoman of the Guard burst in. Informing the Chancellor that he was under arrest, they hauled him off despite his voluble protests. Imprisoned in the Tower, Thomas was flabbergasted to find himself charged and convicted by yet one more Bill of Attainder. And his crimes? You name it - heresy, treason, bribery, misuse of power - Thomas did it. He was even accused of plotting to become King by marrying Henry's first daughter, Mary.

Sitting in the Tower, Thomas was frantic. He wrote long letters to Henry, pointing out his loyal and faithful service and begging the King for "mercye, mercye, mercye." The pleas did Thomas no good. But perhaps Thomas could at least feel some pride of achievement since his letters have become valuable source material for modern historians.

On July 28, 1540, less than three weeks after his arrest, Thomas had his head chopped off. It was pretty rough as executions go. For this job, Henry had skimped on costs. Instead of hiring a skilled practitioner (as he had for Anne), Henry brought in a "ragged and boocherly myser" who we learn "very vngodly perfourmed the office". After multiple whacks Thomas was still alive, and it may have taken up to half an hour from the first to last chop until the executioner could display Thomas's head to the crowd and proclaim "Long live the King!"

Until the end Thomas wondered what the heck he had done to so tick Henry off. And to this day, scholars still debate the matter. But the fiasco of Henry's and Anne's marriage certainly didn't help.

A Ragged and Boocherly Myser

Catherine Howard: Renaissance Valley Girl

Catherine was no "mayde".

Henry's roving - ah - "eye" now lit on a sweet young thing named Catherine Howard. Catherine had been a lady in waiting to Anne of Cleves and was also a cousin of Anne Boleyn. So she and Henry had seen each other pretty steadily for a number of years. With her energetic vivacious personality, Catherine seemed the perfect next Mrs. Henry. Catherine was perhaps eighteen. So she had no flab, no sag, and was quite perky indeed. But there was one, minor, trifling little problem.

There is little doubt in the minds of most historians that Catherine was not the "chaste mayde" Henry thought she was. Far from it. She had been diddling around with various young swains for years where among other things, she had learned to consort with her paramours in a manner that minimized unwanted side effects. But it is also possible - possible, that is - that after she became Queen, she cleaned up her act. Still there were rumors that she still hankered after an acquaintance from her youth, Sir Thomas Culpeper (no double p). Thomas was no mere dashing ne'er-do-well, but had risen to Henry's confidence and was now a member of the Privy Council.

From the first, there were problems in the relationship between Henry and Catherine. By the time of their marriage on July 28, 1540, the King was having a hard time even getting around much less whooping it up with a young energetic bride. To get upstairs he had to be pushed by some of his chamberlains, and he even needed a crane to get onto his horse. His vital statistics were something like 53, 53, 52, and as his surviving armor attests, Henry had finally become the vast wobbling mound of lard of popular image.

By this time Henry's chief advisor was the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer (the "n" comes before "m"). Thomas had never been happy with the rumors of Catherine's youthful peccadillos, and he began an investigation into the Queen's behavior. "Evidence" (note quotes) was not hard to obtain, and soon Thomas came to Henry with a stack of papers which included a letter from Catherine found in Culpeper's room.

The letter starts off politely enough, addressed to "Master" Culpeper, but then becomes decidedly ambiguous. Catherine said she hoped Culpeper could stop by with Anne Boleyn's former sister-in-law, Jane Boleyn, in order that she, Catherine, could "be best at leisure to be at your commandment." She signed it "Yours as long as life endures, Katheryn".

Henry was shocked! shocked! Although Catherine may not been guilty of taking bribes or practicing witchcraft, she was certainly not behaving in a queenly fashion. A Queen of England did not ask Privy Counselors to stop by her private chambers, especially not to be at the Counselor's "commandment". So Henry instructed Cramner to begin a formal investigation.

Once more enhanced interrogation techniques on Culpeper produced the desired results. Or at least Thomas - quote - "confessed" - unquote - to previous misdemeanors with the queen. Another of Catherine's boyfriends, Francis Dereham, admitted that in his salad days he had been far, far too intimate with Catherine. Catherine herself was summoned, and under Cramner's rather intimidating inquiry, admitted that when she was young, Dereham had used her "as a man might use his wife." But all denied any misbehavior once Catherine married Henry.

But that was enough and at Henry's - quote - "request" - unquote - Parliament passed another Good Ol' Bill of Attainder which made it a legal requirement for a queen to report any sordid details of her past life within twenty days of her marriage. Even though Catherine hadn't known of the requirement, in Tudor England ignorance of the law was no excuse even if it wasn't a law yet. She was convicted along with Culpeper, Dereham, and Jane Boleyn.

Culpeper was beheaded on February 10, 1541. Francis, though, was not so exalted as Thomas, and he was hanged, drawn, and quartered. Catherine and Jane Boleyn were themselves beheaded three days later.

Even though she had spent the previous night practicing laying her head on the block, Catherine was shaky on the scaffold. But she confessed to her "crimes" and bade all Englishmen and women to obey and honor their king. Jane also said her execution was "just" since she had lied about her husband, George, during his trial. A number of other relatives of Catherine and Jane were arrested but were later released. Either Henry was getting soft or they didn't have enough money to make it worth his while.

Catherine Parr: Survived (Just Barely)

Try, try, try, try, try, try again.

If at first you don't succeed, try, try, try, try, try, try again. Henry met (sigh) one more lady. This was Catherine Parr. She was about thirty and Henry was now fifty. They were married on July 12, 1543.

You know the old mnemonic about Henry's wives: divorced, beheaded, died / divorced, beheaded, survived. Well, events came close to screwing up the rhyme. Catherine, like Anne Boleyn, had strong Protestant sympathies and, if not a follower, was sympathetic to the teachings of Anne Askew. Anne was a lady preacher and an avowed Lutheran who shockingly proclaimed that the bread and wine in communions remained bread and wine and did not become the body of Christ upon elevation. Henry and his advisors, as protectors of the faith, had Anne arrested, interrogated most enhancedly, and then burned at the stake.

By this time, Henry's religion had definitely taken on a schizophrenic air. If you were a Roman Catholic, you were a potential traitor since you didn't accept Henry's authority over religious matters. If you were a Protestant, you were on the side of Martin Luther, a heretic, and you were liable to be burned at the stake. No one was above suspicion, and Catherine, with her sympathy for Anne Askew, looked very much like a closet Lutheran. So you can bet by now someone on Henry's staff would begin to doubt Catherine's loyalty.

Stephen Gardiner, the Bishop of Winchester, was particularly suspicious of the Queen, and he ordered an investigation into the Queen's beliefs. First, he queried Catherine's ladies about what they believed and read. After they admitted that Catherine had indeed questioned established Church doctrines, Stephen then went to the Tower where he - quote - "interrogated" - unquote - Anne Askew about her contacts with the Queen.

Satisfied he could now prove Catherine was a secret Protestant, Stephen drew up an arrest warrant and took it to Henry. By now Henry was so jaded about his wives, he would believe almost anything. He also remembered that at night during their Bible studies Catherine had debated with him the nature of proper doctrine. That smacked of heresy, and so he took the warrant and signed it.

Somehow Catherine got wind of what was going on (she even saw the actual warrant) and hightailed it to Henry. She denied harboring any heretical beliefs and said her supposed arguing about religious matters was just to divert the King from his infirmities (which was a nice way of saying Henry was a festering mound of fat). She said Henry should ignore her flighty "womanly opinions" and know that she accepted whatever Henry, her lord and liege, taught. This time Henry, in an action that was certainly out of character, simply told her to forget it. Even more out of character, he really meant it. The next day the couple was walking in the garden when a contingent of soldiers burst in to arrest Catherine. But Henry told them to gerrout of it.

The marriage of Henry and Catherine lasted three years and ended with Henry's death. They never had any kids. Catherine then married Sir Thomas Seymour, Jane's brother, and they became guardian of Anne Boleyn's daughter, Elizabeth. She and John had a daughter, Mary, in 1848, but Catherine died less than a week later. So it was Anne of Cleves, who died in 1557, that was the last of Henry's six wives, although Catherine of Aragon - who died at age fifty - was the longest lived.

Henry was 55 years old when he died on January 28, 1548. That was not an unusually premature age by the standard's of the day, but it is young enough so we wonder what Henry had actually died of.

Actually a better question is what didn't Henry die of. By the mid-1540's, Henry was grossly overweight, had gout, and could barely move. He had ulcers and sores on his legs, and possibly deep vein thrombosis or blood clots in his legs. He suffered from horrible constipation, and as this was treated with enemas, certainly made the job of Groom of the Stool less attractive than formerly. With his weight hitting over 300 pounds, a 5000 calorie a day meat rich diet, and complaints of constant thirst, we may infer Henry may have suffered from diabetes, a disease that was inevitably fatal before the twentieth century. In short, Henry could have succumbed from almost anything.

Some historians suspect a major contributor to Henry's not too untimely end was that recent import from the New World, syphilis. Other scholars doubt that the Great Imitator caused Henry's demise since that particular social disease hadn't really been around long enough to filter up from the sailors on the Wapping docks to the English nobility.

There is a story that at his funeral Henry was so bloated that his body exploded. This is mentioned on some sites on the Fount of All Knowledge, but alas, is bogus. The story is actually an old chestnut that keeps getting circulated about various other kings and queens or otherwise unpleasant people. That such a gaseous build up could happen is unlikely since in those days, to embalm a body you gutted it like a catfish. This slowed down the decomposition and would have provided a safety valve for venting. But whatever the state of his corporeal remains, Henry was buried at St George's Chapel at Windsor Castle, and he's still there.

When Henry died his only legitimate son was crowned as Edward VI. It was during Edward's reign that the differences had become irreconcilable between Roman Catholicism and the Anglican Church. The English Church had finally acknowledged its affinity to the Protestant Reformation, although almost uniquely, it maintained much of the flavor of Henry's Old Time religion. Still Edward had no intention of letting his staunchly Catholic half-sister Mary on the throne.

To this end, Edward specified that his successor - should he die "without issue" - would be Jane Grey, the granddaughter of Henry's sister Margaret. Edward, who was something of a prig, did in fact die without an heir at age fifteen. He had ruled only six years. So Jane became queen.

Jane ruled for a full nine days. Yes, that's nine days. Armies fighting on Mary's behalf marched on London, and the battalions who championed Jane marched out to meet them. It was clear, though, that the average Englishman favored Mary, and the undermanned army of Jane failed to recruit any new troops. Seeing defeat was inevitable, the soldiers of Jane's army declared their allegiance had been coerced and switched sides. Mary became Queen.

Right away Mary tried to restore papal authority over England. But unfortunately, the average Englishman's opinion was not that of the ruling classes - or at least the classes who ran the armies. Still, Mary did her best and chopped off many a head with an élan that would have pleased her father. The chopping included Lady Jane, and to show she was really her daddy's girl, Mary also burned at least two hundred people at the stake. That included Thomas Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury and one of Henry's last loyal ministers.

Thomas, though, had been willing to meet Mary more than half way. After his arrest, he recanted his Protestantism, saying he had erred and realized Catholicism was the true religion. Mary was most grateful for Thomas's conversion but went ahead and burned him anyway. So just to spite Mary, as he was being tied to the stake, Thomas recanted his recantation. Mary lived until 1558, and died without an heir, one of the most reviled figures in English history.

The next in line was Elizabeth, Anne Boleyn's daughter, and she became Queen on November 17, 1558. Elizabeth immediately switched the country back to Protestantism and ruled until 1603. Elizabeth is regarded as one of England's greatest monarchs, and in addition to things like sponsoring Sir Francis Drake's voyage around the world and defeating the Spanish Armada, she banned swearing in plays and made Shakespeare cut out such horrible profanity like "Zounds!", "S'blood!", and "Tush!"