Leopold Stokowski

(Leopold!)

Leopold Stokowski

The Orchestra Builder

It's rare that conductors achieve lasting fame. Those who did actually served double duty as composers. Gustav Mahler. Richard Strauss. Richard Wagner. They were conductors, yes, but composers first. Conductoring fame itself is fleeting.

Huh! say the critics. What kind of ignoramus makes that kind of asinine statement? After all, what about John Barbirolli, Sergiu Celibidache, Ferenc Fricsay, and Pierre Monteux?

Or even (and to skip this rather long list click here) János Fusz, Salvatore Pappalardo, John William Glover, Charles E. King, Alexander Koshetz, Patrick Conway, Luigi von Kunits, Alessandro Rolla, Johannes Bernardus van Bree, Thomas Helmore, Ferruccio Busoni, Timoteo Pasini, Emma Roberto Steiner, William Sterndale Bennett, Ferdinand Löwe, Miina Härma, Károly Thern, William Pitt, Hugo Reichenberger, Richard Strauss, Serafino Amedeo De Ferrari, Carl Bergmann, Griffith Rhys Jones, Emanuele Muzio, Conradin Kreutzer, Jan Nepomuk Škroup, Andonios Liveralis, Julián Carrillo, Theodore Thomas, Carlo Pedrotti, Charles Constantin, Lucien Southard, Giovanni Bottesini, Louis Schindelmeisser, Rodolphe Kreutzer, Joaquín Gaztambide, Emil Młynarski, Carlo Ercole Bosoni, Charles Hallé, Hans Richter, Carrie B. Wilson Adams, Luigi de Baillou, Alphonse Varney, Gotthold Carlberg, Jean-Baptiste Accolay, Eduard Grell, Julius Benedict, Otto Singer, Jules Garcin, Adolf Rzepko, Ferenc Erkel, Joseph Labitzky, Philippe Musard, August Eberhard Müller, Karl Doppler, Lorenzo Molajoli, Carl Nielsen, Giuseppe Dell'Orefice, Anatoly Lyadov, Alfred Mellon, Eugène Ysaÿe, Adolf Čech, Hans Christian Lumbye, Carl Reinecke, Carl Friedemann, Guillaume Couture, Louis-Antoine Jullien, Johann Gottfried Piefke, Franz Abt, Robert Sands, Carl Amand Mangold, Václav Suk, Adolf Neuendorff, Achille Peri, Adolf Friedrich Hesse, Catharinus Elling, Frank Bridge, Heinrich Dorn, A. J. Turner, William Cusins, Alexander Mackenzie , Antonio Buzzolla, Johann Nepomuk Fuchs, Atanasio Bello Montero, Ludvig Norman, Lewis Henry Lavenu, Carl Martin Reinthaler, Jean-Baptiste Arban, Jules Pasdeloup, Anthony Heinrich, Johann Joseph Abert, Anton Seidl, Giuseppe Martucci, Joseph Gungl, Harley Hamilton, Robert Schumann, Ferdinand Giovanni Schediwy, Joseph Hellmesberger Sr., Albert Becker, John Fawcett, François George-Hainl, Achille Graffigna, Otto Sutro, Vinzenz Lachner, Max Bruch, Antonio D'Antoni, Otto Nicolai, Samuel Maju Samehtini, August Röckel, Henry Kimball Hadley, Tokichi Setoguchi, Hollis Dann, Jakob Zeugheer, Franz von Suppé, Balduin Dahl, Adam Itzel Jr., Fritz Scheel, Alfred Hill, Franz Lachner, Ignaz Lachner, Charles Sauvageau, Jean-Chrysostome Brauneis I, Wilhelm Rust, David Wallis Reeves, Heinrich Proch, Henri Büsser, Johannes Verhulst, Holger Simon Paulli, J. E. Goodson, Wilhelm Stenhammar, Alberto Williams, Norman O'Neill, Walter Cecil Macfarren, Ludolf Nielsen, Henry Wylde, Jan Kalivoda, Julius Rietz, Felix Otto Dessoff, Michael Costa,, Richard Hol, Joseph Barnby, Philippe Decker, James Hewitt, Thomas Wingham, Antonio Reparaz, Dionysius Rodotheatos, Filip von Schantz, Ernst Richter, Carlo Evasio Soliva, Lorenz Nikolai Achté, Siegmund von Hausegger, Ferdinand Hiller, Pierre-Louis Hus-Desforges, Johann Baptist Krall, Hans Balatka, Blas de Laserna, Stanisław Moniuszko, Mikhail Tushmalov, Wilhelm Jahn, Carl Riedel, Frank Van der Stucken, Adolphe Deloffre, Franco Faccio, Henry Christian Timm, Louis-Albert Bourgault-Ducoudray, Josef Szulc, Georg Hellmesberger Sr., Heinrich von Herzogenberg, Rodolfo Ferrari, August Lanner, Joseph Holbrooke, Carl Friedrich Zöllner, Leopold Damrosch, Tor Aulin, Henri Berger, Hildegard Werner, Angelo Mariani, Hermann Levi, Nikolay Afanasyev , Karl Wilhelm,, Leonid Malashkin, Adolphe Samuel, Michael Flagstad, John Charles Bond-Andrews, Frederick Albert Bridge, Jacopo Foroni, Vittorio Monti, Edward Clark,, Chiquinha Gonzaga, Mieczysław Karłowicz, Juan de Dios Alfonso, Alexander Glazunov, Tigran Tchoukhajian, Hugo Riesenfeld, Franz von Jauner, Louis Köhler, Helen May Butler, Giuseppe Staffa, Harvey B. Dodworth, Ureli Corelli Hill, Joseph Robinson, Karel Kovařovic, Patrick Gilmore, Walter Bache, Felix Mendelssohn, George Alexander Macfarren, Louis Désiré Besozzi, Friedrich Baumfelder, Francisco Nicasio Jiménez, Arthur Nikisch, Albert Visetti, Karel Bendl, Edward German, Mykola Leontovych, Ludwig Bussler, Béla Kéler, Henry David Leslie, Karol Lipiński, Giulio Alary, George Loder, Max Erdmannsdörfer, Pavel Křížkovský, Édouard Deldevez, Luigi Ricci, Karl Anton Eckert, Johann von Herbeck, Felix Blumenfeld, Jacob Niclas Ahlström, Alfred Cellier, Franz Clement, Agide Jacchia, Pietro Antonio Coppola, Fabio Campana, Alfred James Phasey, František Zdeněk Skuherský, Charles Lamoureux, Wilhelm Friedrich Wieprecht, Pierre-Louis Dietsch, Herbert Clarke, Heinrich Porges, Theodore Eisfeld, Moritz Heuzenroeder, Claudio Brindis de Salas, Giacomo Panizza, Niels Gade, Jean-Baptiste Labelle, Eugenio Cavallini, Johan Svendsen, Robert Prescott Stewart, Cenobio Paniagua, Edward Kendall, Aleksander Zarzycki, Heinrich Esser, Gaetano Molla, Reynaldo Hahn, Wilhelm Joseph von Wasielewski, Henry Schoenefeld, and Karel Komzák I. [To return to the top of the list click here.]

Well, perhaps we are speaking in too sweeping of generalizations. With the advent of the recording industry there are some conductors who did nothing but conduct. But still, if you ask Joe and Josephine Blow on the street about Lorin Maazel, Thomas Beecham, Wilhelm Furtwängler, Herbert von Karajan, Pierre Boulez, and Neville Marriner, you'll get a blank look.

Perhaps it's this fleeting fame and historical anonymity of conductors that in recent years has led people to ask:

|

Just what the hey does an orchestral conductor do? |

Well, for one thing we know the conductors set the time and determine how loud and soft everyone plays. And when you get down to it, that's pretty much what "interpreting" a piece of music is.

Most of all, though, we're told that in our modern era, it's the conductor who keeps the group together. Before the 19th century the conductor was also a player - usually a keyboard player (like harpsichord) or the first violin (even now usually called the concertmaster). But the ensembles were small and the concert halls intimate. So keeping together wasn't a problem.

But with today's larger orchestras, players can hear only themselves and their immediate neighbors. And on the larger stages the sound takes about 1/10th of a second to travel from one end to another. That may not seem like much but the delay in the sound traveling from one musician to the other is enough to throw the timing off.

But we wonder. In the Young People's Concerts Leonard Bernstein would sometimes play the piano and the orchestra didn't need to have anyone standing up waving their arms. And the comedian Danny Kaye would often conduct orchestras as one of his comedy routines. At one point he would look into the audience and see someone he knew. He'd then walk down from the podium and talk with his friend and others in the audience. All the while the orchestra kept playing without any difficulty.

Everyone knew Lenny ...

But whether they are vital keystones in modern concerts or overpaid superfluous white-tied martinets, there was a time that conductors were public figures. Even in the later 20th century, everyone knew who Lenny was. And Eugene Ormandy. And even before Lenny and Eugene, you had Arturo Toscanini.

And yes, you had Leopold Stokowski.

... and Eugene

But why were conductors in the news, for crying out loud? Wasn't there enough other stuff to report?

Well, not really. Before the 1950's - when someone named Elvis showed up and the concept of the teenager emerged - entertainment was almost exclusively directed toward adults. There was also the tendency to promote highbrow culture. Country and western music was still disparaged as "hillbilly music" and even jazz was seen as somewhat disreputable.

So in the early 20th century concerts and recitals were commonly reported in the newspapers. If so-and-so was conducting the such-and-such Philharmonic or if Joe Blow the famous classical musician was giving a recital, you'd see it even on the front pages.

And although there was no television, there was the newsreel. These were brief films shown in movie theaters before the main attraction and featured recent news items.

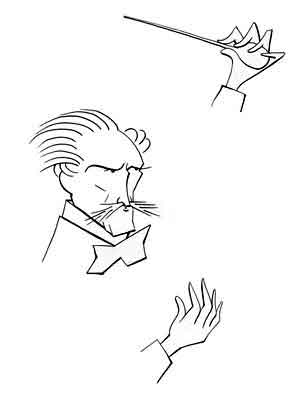

And standing on the podium with his shock of mane-like hair, Leopold made great copy. Whether it was taking his orchestra on tour or conducting the premiere of the 7th Symphony ("Leningrad") of Dmitri Shostakovich, all the world saw Leopold Stokowski. In the 1930's he also appeared as himself in a movie called "One Hundred Men and a Girl". And like many conductors of major orchestras, his presence on the podium was a performance in itself.

So it's no surprise that in 1937 when Walt Disney walked into a Beverly Hills restaurant and saw Leopold Stokowski sitting at a nearby table, the two men ate lunch together. Before the meal was over, Walt had persuaded Leopold to conduct the orchestra for the sound track of his planned movie Fantasia. And in the movie, Leopold actually shakes hands with Mickey Mouse!

Walt Disney

The two men met.

Although now hailed as a cinematic masterpiece, Fantasia has been described as Walt's first real failure. It wasn't until the 1960's flower power hippies embraced the film that it re-entered contemporary culture. So when the hippie motifs went mainstream, so did Fantasia.

On the other hand for young kids the movie was - and remains - a flop. After a recent showing, a little girl turned to her mother and asked, "Where were the cartoons?" The father commented on his kids' reactions. "I think they were bored out of their minds." You suspect that went for him, too.

If young kids didn't quite "get" Fantasia or even remember who the guy who shook hands with Mickey was, in 1949, Warner Brothers released, "Long Haired Hare". This was an animated cartoon where Bugs walked into the concert hall where baritone Giovanni Jones was performing. As Bugs, complete with Leopold's trademark coiffure, moves to ascend the podium, the orchestra members start in amazement as Bugs walks by, each saying, "Leopold!"

Of course Bugs/Leopold causes complete mayhem as with exaggerated and flamboyant gestures he conducts the singer. But even as the animated cartoon faded from movie theaters to be replaced with commercials, they became a staple of kids' television shows - where the cartoons were repeated ad infinitum after school and on Saturday morning. So Leopold (Leopold!) became fixed into America's 20th century cultural consciousness.

... and Arturo.

Music critics are generally charitable toward the various gyrations and grimaces of the orchestral conductor. They say the mannerisms communicate how the orchestra should play in ways that can't be expressed in words. But even a maestro like Leonard Bernstein realized a conductor's flailings sometimes look comical. When he was studying at the Curtis Institute, his teacher told him to practice in front of the mirror. Lenny tried it and burst out laughing. He never practiced in front of a mirror again.

On the other hand, scientific analyses indicate conductors do make a difference. Blind studies found that professional music critics rated the orchestral music better if the director was an established and experienced (and even "authoritarian") conductor rather than a mild mannered and courteous beginner. So the contortions seem to have a real purpose.

Although critics were impressed with Leopold, some of his acquaintances were put off by what they saw as affectations. In fact, rather severe and even pejorative words have been used. As one of Walt's animators, Shamus Culhane, put it:

Stokowski had to be the biggest poseur since Richard Wagner. One afternoon while Stokowski and Disney were involved in a story conference. The refreshment cart was wheeled in. Walt turned to Stokowski and inquired politely, "Care for a Coke?" Leopold looked blank, "Ah, Coke? What is that?" Disney explained that it was a soft drink. When he was handed a paper cup of the most advertised liquid on earth. Stokowski looked at it as if it was a Chateau Margaux of suspicious vintage. He took a cautious sip, rolled it around in his mouth in approved wine taster's style, and swallowed. "Quite good," he murmured, "really quite good."

Sometimes Leopold's "posing" may have been honest attempts at innovating teaching. One member of an orchestra that fell under Leopold's baton was a young trombonist right out of college. He remembered that when Leopold first took the podium he held up his hand, pointing the index finger toward the musicians. He told them to begin playing on cue.

But instead of lifting his arm to give the downbeat, he began slowly rotating his arm so the hand and finger were tracing out a circle. Uh, Mr. Stokowski, the musicians asked, how do we know when to come in?

"Use your sixth sense," he replied.

Was Leopold "posing"? Who knows? But the young trombone player said it worked

Certainly the most cited example that - quote - "proves" - unquote - Leopold's alleged - quote - "posing" - unquote - was his accent.

Those who don't know about Leopold's early years and see his name assume his elocution was simply a basic Eastern European twang with an overlay of English. And certainly if you listen to interviews Leopold gave in his early years, some words have a distinct British twist and the discerning listener can even get an overlay of American slipping through.

Some critics have been downright harsh on Leopold. One writer said flat out that everything about Leopold - excepting his musicianship - was a fake, and that he once walked out of a BBC interview when the reporter pointed out his humble and very English beginnings.

The truth Leopold was born April 18, 1882, as Leopold Anthony Stokowski (some sources flip the first and second name) in Marleybone, London, England. Some have said this proves Leopold was a cockney. But they are confusing the Marleybone district with St. Mary le Bow Church where if you live within earshot of the bells then you're a real cockney. Marleybone is actually a couple of miles off.

But although Leopold's dad, Kopernik Józef Boleslaw Stokowski, was born in Poland, his mom, Annie Moore, was Irish. It's hard to believe that Leopold growing up in London would not have spoken with the accent of the region. So it's natural - and perhaps correct - to believe that a manufactured "Stowkowskiesque" accent emerged only after he began to pursue his musical and public career.

A prodigy, Leopold was admitted to the Royal College of Music at age 13. He found his métier as an organist and in only a couple of years he was playing in churches around the city. Leopold graduated with a BA in Music from Oxford in 1900, and began to conduct choirs in churches in London. His reputation as a choirmaster reached across the water (as J. R. R. Tolkien might say), and he was offered the job as choirmaster at St. Bartholomew's Episcopal Church in New York. Then - and now - the church boasts of one of the most gargantuan organs in the world.

Then in 1909 the Cincinnati Orchestra advertised for a conductor. Leopold applied and although he had no orchestral experience, he was hired. This Midwest stint, though, was brief and in 1912, he moved to Philadelphia.

The story is that Leopold had soured on Cincinnati's orchestral managers and the friction twixt the conductor and the board - a recurring theme - prompted his move. However, there are some who wonder if the fractious relationship was synthetic and crafted by Leopold to get out of the multi-year contract so he could move to the City of Brotherly Love.

It's natural to think that Leopold's well-known eschewing of the baton for simply waving his hands was because that's the standard technique for choir directors. However, an early photo of Leopold at Cincinnati shows him using a pretty long stick. But in Philly he did toss the baton aside.

Leopold was noted for getting rid of musicians he didn't think up the snuff. When taking the helm of one orchestra he booted out a good chuck of the players and replaced them with players he thought did have the snuff. Even in guest stints he demanded absolute authority. One orchestra had a principal flautist who never missed a note and could play anything put in front of him. But when Leopold showed up as a guest conductor, the flute player couldn't play soft enough to suit the Stokowskian demands. So the player was out for the duration of Leopold's tenure - which since he was a guest conductor was brief.

Whether Leopold's perfectionist philosophy really created the "Philadelphia Sound" of the Philadelphia Orchestra - lush, rich, and sonorous - has been questioned - and by Leopold himself! He even doubted if the Philly Sound really existed. "When a conductor rehearses an orchestra," Leopold said, "who makes the sound? He doesn't make the sound. The players make the sound."

Why did Leopold want to go to Philly? Well, without doubt it was the prestige. For much of the twentieth century the "Big Five" of American Orchestras were the New York Philharmonic, the Cleveland Orchestra, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the Boston Symphony, and, yes, Philadelphia. So Philly was pretty much the place for Leopold to be. But although he stayed in Philly for over thirty years, eventually Leopold again fell afoul of the orchestra's managers. He began sharing responsibility with the capable Eugene Ormandy. Then in 1941, Leopold split for good and Eugene took over.

In 1944, Leopold accepted an offer from New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia to conduct the New York City Symphony Orchestra (not to be confused with the New York Philharmonic). His tenure there lasted only a year, as again he quarreled with the board of directors. So in 1945 he formed the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra in Los Angeles. Then while Leopold still spent a good amount of time guest conducting, from 1949 to 1950 he also shared responsibility with Dmitri Mitropoulos directing the New York Philharmonic after which Dmitri took over on a full time basis. Leopold also organized the National Youth Orchestra and took it on an international tour. He also took over the NBC Symphony for a couple of years when Arturo Toscanini took a hiatus.

In 1955 the Houston Symphony was looking for a conductor and asked Leopold if he'd take the job. Leopold said fine, and he remained in the Lone Star State for six years. What prompted his departure was when he had picked three groups of singers for a concert. But when word got out that one of the Leopold's choices was from Texas Southern University, a then all-black college, the other (and white) singers refused to perform. Leopold immediately left, saying he could not work "in an environment so full of prejudice".

It's often forgotten how segregated orchestras were, not just regarding race, but with gender. If you look at the New York Philharmonic even in Lenny's years, it was overwhelmingly white and male.

Leopold had always deplored such segregation and lack of diversity (as did Lenny). And it was Leopold who in 1930 had hired principal harpist Edna Phillips as the first full time woman musician in Philadelphia. It took longer to break the barrier in New York, but in 1966 Lenny hired Orin O'Brien as a double bassist (Orin at this writing is still playing in the group). It's still surprising to see how long major symphony orchestras have resembled an all-boys club and some even famous orchestras had no full time women performers until relatively recently.

Although none of Leopold's stints with orchestras were anywhere near as long as his tenure at Philadelphia, by now Leopold could make a living as a guest conductor. It's natural to wonder how much a top-notch conductor makes, particularly since most orchestras are struggling to survive.

Today, of course, conductors pick up seven figured salaries which, to be honest, are actually quite small compared the dough pulled in by other celebrities. But even adjusting for inflation, Leopold's fees don't seem that high. In 1970 Leopold got about $700 for a guest concert - which even correcting for inflation and given the fact that this also includes the time for travel and rehearsals - is not all that much.

On the other hand, at Philadelphia Leopold definitely was paid well. His salary in 1938 was over $110,000. That was big money at the time, although again not what the top-flight industrialists raked in.

Leopold's final full-time conducting stint was when the New York Philharmonic decided to vacate Carnegie Hall and move to the Lincoln Center. So Leopold was asked if he'd form a new orchestra to fill Carnegie's void.

He was happy to oblige and from 1961 to 1972, Leopold performed as the conductor of the American Symphony Orchestra. To help keep costs and ticket prices low, he did so for no pay and even picked up certain expenses out of his own pocket.

Leopold was over ninety and figured it was time to return to England. His last public concert was May 14, 1974, where he led the New Philharmonia Orchestra in the Royal Albert Hall in London. But he was definitely an optimist, and he signed a six-year recording contract. Leopold died in 1977, age 95.

References

The Mystery of Leopold Stokowski, William Ander Smith, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1990.

"Do Orchestras Really Need Conductors?", Shankar Vedantam, All Things Considered, National Public Radio, November 27, 2012.

"Leopold Stokowski - British Conductor", Encyclopedia Britannica.

A History of Orchestral Conducting: In Theory and Practice, Elliott Galkin, Pendragon Press, 1986.

"The Fantasy of Disney's 'Fantasia'", Dick Adler, The Chicago Tribune, September 23, 1990.

"Long-Haired Hare", Charles M. Jones (Director), Michael Maltese (Writer), Mel Blanc (Voice), Nicolai Shutorev (Voice, uncredited), Warner Brothers, 1949, Internet Movie Data Base.

"Fantasia 2000 - Disney's First Flop Remade", Fiachra Gibbons, The Guardian, December 21, 1999.

One Hundred Men and a Girl, Henry Koster (Director), Bruce Manning (screenwriter), Charles Kenyon (Screenwriter), Deanna Durbin (Actor), Leopold Stokowski (Actor), Universal, 1937, Internet Movie Data Base.

"How Conductor Leopold Stokowski Popularized Orchestral Music in America", Colin Eatock, Playbill, April 18, 2018.

"Leopold Stokowski: The Contrary Conductor", BBC World Service, June 6, 2001.

Talking Animals and Other People: The Autobiography of One of Animation's Legendary Figures, Shamus Culhane, St, Martins Press, 1986, p 197.

"Disney's 'Fantasia' Was Initially a Critical and Box-Office Failure", Neal Gabler, Smithsonian Magazine, November 2015

"Composer or Conductor?", Paul Hume, The Washington Post, September 30, 1979.

"19th Century Conductors", Wikipedia.

"Maestro Leopold Stokowski Started Career at Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra", Jeff Suess, Cincinnati Enquirer, May 24, 2017.

"Philadelphia Orchestra", Joseph Schiavo, Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia.

"Music Directors and Advisors", New York Philharmonic.

"Leopold (William) Stokowski", Dictionary of Midwestern Literature, Volume 1: The Authors, Philip Greasley (Editor), Indiana University Press, 2001.

"The Maestro's Mojo", Daniel Wakin, The New York Times, April 6, 2012.

"The First Woman Member Of The New York Philharmonic Is Still Playing", Arts Journal, August 7, 2015.

The Maestro Myth: Great Conductors In Pursuit of Powers, Lebrecht Norman, Simon and Schuster, 1991.

"What do conductors do? Do orchestras really need someone flapping their arms on a podium?", Ivan Hewett, The Telegraph, May 1, 2014.

"What Is the Point of Conductors for Orchestras? Don't the Musicians Know the Music?", The Guardian, 2011.

'Most of the Orchestras in the World Can Play Without a Conductor'", Michael Dervan, The Irish Times, November 25, 2010.

"Shocking Stat: Four Composers Make up 24% of Music Played by Major US Orchs", Norman Lebrecht, Slipped Disc, September 22, 2016.

The Stokowski Legacy, stokowski.org.