Truman Capote

(With a Comparison of the Famous Book In Cold Blood with Excerpts from Contemporary Newspaper Articles, Documents, and Transcripts Plus a Bit of Johnny Von Neumann's Game Theory Thrown In)

Truman Capote

After

(Not in Kansas)

- It's better that one innocent man be punished than that a dozen guilty men go free.

- Truman Capote

"Truman, I don't think you're in Kansas anymore."

There are authors who were one hit wonders and those who were not. Truman Capote was one of the rare individuals who was not, but it's easy to think he is.

Or at least if anyone knows who Truman Capote was, they remember only one book. That, of course, is In Cold Blood which tells the story of the murder of the Clutter family of Holcomb, Kansas.

On the afternoon of Saturday, November 14, 1959, two ex-convicts, Richard Eugene Hickock and Perry Edward Smith, left the small Kansas town of Olathe (pronounced oh-LAY-thuh), about twenty miles south of Kansas City. They drove almost 400 miles to Holcomb situated about 60 miles east of the Colorado border and seven miles from Garden City, the county seat of Finney County.

Sometime after midnight they arrived at the Clutter's River Valley Farm. Then they entered the house where Dick believed that Herbert Clutter, a wealthy farmer, kept $10,000 in a safe.

Dick had heard the story from a former cellmate, William Floyd Wells, who in the late 1940's had worked for Mr. Clutter. Floyd said that Mr. Clutter had a safe where he kept his money (actually Mr. Clutter handled virtually no cash and did almost all his business by check). We read that Dick told Floyd that once he got out he and his friend Perry would rob Mr. Clutter and "leave no witnesses".

Armed with a hunting knife and a 12-gauge shotgun, Dick and Perry woke the family: Mr. Clutter, his wife Bonnie, and their two teenage children, Nancy and Kenyon. They bound Mr. Clutter and Kenyon in the basement, and Bonnie and Nancy were tied up in their beds.

The two men searched the house. Finally realizing there was no safe, they took away a portable radio, a pair of binoculars, and maybe $50 in cash. They then cut Mr. Clutters throat and shot him in the head. Next they proceeded through the house and shot the rest of the family. They returned to Olathe.

The pair left Kansas a few days later and drove to Mexico. There they sold Dick's car and pawned the items taken from the Clutter home. Taking a bus back to the US, they financed themselves by Dick's skill in writing hot checks. Amazingly they even returned to Kansas City where Dick again "hung paper" as he called it before heading west.

Then Floyd Wells, who was still in prison, heard about the Clutter murders on the radio. He told the authorities he believed he knew the killers. On December 30, Dick and Perry were arrested in Las Vegas, ostensibly as parole violators and for passing hot checks.

Upon questioning by agents of the Kansas Bureau of Investigation (KBI), Dick finally admitted his part in the crime. But he insisted that Perry had done the actual killing. When Perry learned of Dick's duplicity, he also confessed, insisting that he killed Mr. Clutter and Kenyon and Dick killed Bonnie and Nancy. Five years later both men were executed by hanging on the gallows of Kansas State Penitentiary in Lansing. Because the gallows was in the corner of a storage warehouse, the men were said to have "gone to the Corner".

In Cold Blood was first published as a four part series in The New Yorker in 1965. When it was issued as a book early the next year, it was an instant bestseller and made Truman rich and famous. But more importantly it solidified his literary legacy as the inventor of the nonfiction novel.

Fiction vs. Nonfiction (And Vice Versa)

And what, we ask, is a "nonfiction novel"?

Well, the Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines a "novel" as:

An  INVENTED prose narrative that is usually long and complex and deals especially with human experience through a usually connected sequence of events.

INVENTED prose narrative that is usually long and complex and deals especially with human experience through a usually connected sequence of events.

And another Merriam-Webster definition is

A  FICTIONAL prose narrative of considerable length and some complexity that deals imaginatively with human experience through a connected sequence of events involving a group of persons in a specific setting.

FICTIONAL prose narrative of considerable length and some complexity that deals imaginatively with human experience through a connected sequence of events involving a group of persons in a specific setting.

That's an  INVENTED and

INVENTED and  FICTIONAL prose narrative that deals

FICTIONAL prose narrative that deals  IMAGINATIVELY with human experience.

IMAGINATIVELY with human experience.

And yet, In Cold Blood, Truman assures us, is completely factual.

Hm. There's something amiss here.

How can an "invented" or a "fictional" prose narrative that deals "imaginatively" with human experience be completely factual?

Isn't "nonfiction novel" a contradiction?

But wait! The Merriam-Webster's dictionary lists the oldest definition first. So perhaps we've read the definition for the word "novel" back then, but not the definition now.

So let's turn to the American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. This, we read, gives us the most common and currently used definition first. And turning the pages (or clicking the mouse) we find the American Heritage Dictionary defines a novel as

A fictional prose narrative of considerable length, typically having a plot that is unfolded by the actions, speech, and thoughts of the characters.

Once more we have a  FICTIONAL prose narrative.

FICTIONAL prose narrative.

So indeed it seems that Truman was speaking in conundrums.

Humpty Steps In

At this point we turn to the one scholar who has the remarkable ability to clarify discussions. That's Humpty Dumpty as he appears in Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking Glass.

When Alice pointed out that Humpty was using words wrong, he replied, "When I use a word it means just what I choose it to mean - neither more nor less. The question is which is to be master - that's all."

Definitions, in fact, are arbitrary, and we decide what they mean. We can keep them, change them, and create new ones.

And we do indeed find a new dictionary entry that arose in the mid-20th century.

A  nonfiction novel is defined as:

nonfiction novel is defined as:

A  factual or

factual or  historical narrative written in the

historical narrative written in the  form of a novel.

form of a novel.

And to supplement the definition, the entry adds:

Truman Capote's In Cold Blood is a nonfiction novel.

Truman Capote's In Cold Blood is a nonfiction novel.

That's a factual or historical narrative.

So today the word "novel" must needs have refer to a literary form. If we are to be the masters, then, a "nonfiction novel" is by no means a contradiction.

And more to the point, the definition specifically gives Truman's In Cold Blood as an example!

Meet Mr. Capote

Ironically for someone who later became a quintessential member of the FAH-bu-lous New York jet set (to use a rather outdated term), Truman Capote was a Southerner. Born in Louisiana in what is called a "broken home" (his birthname was Persons), his early upbringing was with his mother's Alabama and Mississippi relatives. However, he seems to have been able to make friends easily and among his childhood chums was Nelle Harper Lee, later to write the now classic and Pulitzer Prize winning novel To Kill a Mockingbird.

In 1932 Truman moved north to Connecticut to live with his mother and her second husband, Joseph Capote. Joseph legally adopted Truman, and so Truman Persons became Truman Capote.

Showing an interest (and talent) in writing while still a kid, Truman attended secondary schools around New York. But by the 1940's Truman had decided to become a writer and forswear college and so following the path of other literarily university non-graduates like Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, John Steinbeck, Mary Lou Angelou, and William Shakespeare.

After getting a job as a copyboy for The New Yorker, then as now the nation's #1 literary magazine, Truman took the traditional literary pathway of submitting stories to magazines "on speculation" as it's called. This was a time when nationally circulated "general interest" magazines accepted (and paid) for fiction. In 1945 Truman sold his first short story, "Miriam", to Mademoiselle. The story won the O. Henry Award for the best first story, and so at age 21, Truman was an award winning author.

Most of Truman's stories have been classified as "Southern Gothic", a literary tradition made most famous by Truman's contemporary, Flannery O'Connor. In Southern Gothic tales, you have plots where ordinary people find themselves in quite un-ordinary, often troubling, and even creepy circumstances.

Flannery O'Connor

Southern Gothic

Soon Truman's stories had attracted the attention of established authors and other serious literati. Carson McCullers, also a Southern Gothic writer, managed to get him accepted into the famous Yadoo writers colony in New York where he wrote his first novel, Other People, Other Rooms. The story was inspired by Truman's own childhood and was fairly well received.

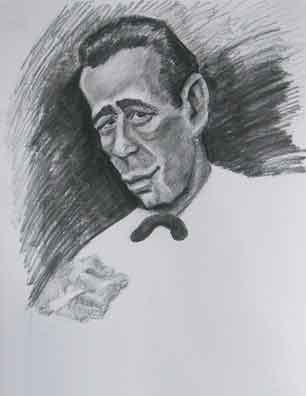

Humphrey Bogart

Truman accepted his challenge.

Less well known to the general public is that in addition to establishing a career as a short-story writer and novelist, Truman also wrote plays and even worked in Hollywood as a screenwriter. There's the famous story that on the set of Beat the Devil, Humphrey Bogart was taking on all comers at arm wresting. Truman looked on and dismissed winning at the supposedly macho competition as a trick. Then accepting Humphrey's challenge, Truman beat him three times in a row. Immediately an irate Humphrey challenged the small and slight writer with the high pitched voice to a full-fledged fight. Truman immediately dumped Humphrey on his rear end with a judo toss.

Jackie

A Friend

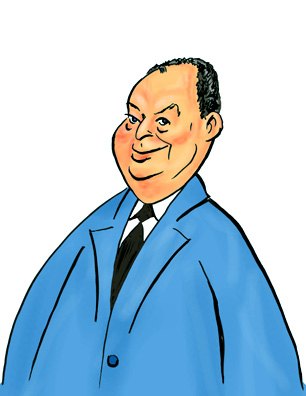

Truman, though, still had his home base in Manhattan. A gregarious and entertaining companion, he included among his friends the CBS mogul, William Paley and his wife Barbara (called Babe), Jackie Kennedy and Jackie's sister, Lee (who married the Polish nobleman, Prince Stanisław Albrecht Radziwiłł and so became Princess Lee Radziwiłł), and Random House owner Bennett Cerf. It was Bennett who in 1958 published Truman's short novel, Breakfast at Tiffany's. The novel and the 1961 film - starring Audrey Hepburn - transformed Truman into the now rare phenomenon, the celebrity author (not to be confused with the more modern phenomenon of the celebrity-turned-into-an-author).

After his successes, Truman had become a regular contributor to The New Yorker. In November 1959, he called up his friend Slim Keith and said he had a couple of choices for a new article. For one he could follow around a lady who never saw the people she worked for, and the other was to go to a small town in Kansas and write how a recent murder affected the community. "Do the easy one," she said. "Go to Kansas."

Truman and His Genre

First of all, Truman did not claim he had invented the nonfiction novel. There were earlier writers like military historian Cornelius Ryan who wrote non-fiction in the novelistic form. But Truman did say he brought the concept to a higher level of development than others had.

To duly give Truman credit, it appears that he did indeed coin the actual term "nonfiction novel". And if In Cold Blood is not the first of the genre, it is certainly the most famous.

Truman was emphatic about the non-fiction part. Anyone writing a non-fictional novel, he said, must adhere to rigid standards of accuracy. Or as he said to his friend and fellow-writer George Plimpton:

The nonfiction novel should not be confused with the documentary novel - a popular and interesting but impure genre, which allows all the latitude of the fiction writer, but usually contains neither the persuasiveness of fact nor the poetic attitude fiction is capable of reaching. The author [of documentary novels] lets his imagination run riot over the facts!

So in crafting one definition, it seems we've stumbled into another. Just what is a "documentary novel"?

Well, according to the Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of Literature we find the definition:

documentary novel \,dăk-yu̇ 'men-tə-rē\: Fiction that features a large amount of documentary material such as newspaper stories, trial transcripts, and legal reports. Examples include the works of Theodore Dreiser.

So the "documentary novel" is indeed fiction. But the plot of a documentary novel does incorporate real events and their documentation - hence the name.

In contrast with the (ptui) "impure" documentary novel and to insure the complete veracity of In Cold Blood, Truman assures us he conducted meticulous research. This included not just examining the relevant documents but he also undertook extensive interviews with the people involved.

To get the people to speak freely and openly, Truman said he did not take notes or use a tape recorder. Instead, Truman said he trained himself to remember their actual words with over 90% accuracy. So when you read quotes from In Cold Blood you're reading what was actually spoken.

But the true peculiarity of the nonfiction novel, Truman said, is that it is not something to be undertaken by professional journalists and reporters. Their training is inadequate to present the factual events in the form of a novel. Only experienced fiction writers could do that.

Taking Up Truman's Gauntlet

Not surprisingly journalists and reporters saw Truman's words as a challenge. And they took the gauntlet up mit gern. In fact, as one writer pointed out, the appearance of In Cold Blood established a veritable cottage industry in debunking Truman and his book.

An immediate topic for the debunkers was whether anyone could write down verbatim conversations without notes or making a recording. If you believe you can do this, one journalist snorted, you're deluding yourself.

Even George Plimpton - remember he was a friend of Truman's - seemed dubious. "Sometimes [Truman] said he had ninety-six per cent total recall," George said, "and sometimes he said he had ninety-four per cent total recall. He could recall everything, but he could never remember what percentage recall he had."

Like many writers of history, Truman did not do everything by himself. During many of the interviews he was accompanied by his friend, Nelle Lee, who had just finished To Kill a Mockingbird. With her congenial but forthright personality, she was particularly helpful in smoothing the way between Truman and the townspeople in Kansas.

One interviewee specifically remembered Nelle taking notes, and Nelle's biographer said she had reams of notes which she handed over to Truman. But in other cases we read that neither Nelle nor Truman scribbled while they worked. Instead they would write up what they remembered separately. Then they would get back together and come up with what they felt were the actual words.

But it doesn't matter how many people are not taking notes, the critics say. At best if you just write from memory, you still get only an approximation of the actual words.

That said, other nonfiction writers - even scholars - have used Nelle and Truman's method without criticism. Vance Randolph, when gathering the stories for his masterful Pissing in the Show and Other Ozark Folktales, did not take notes1. Like Truman, he would write the information down within a few hours. But Vance was up front about these - ah - "folk tales". Not one was a verbatim transcript, he said, even though he said all were pretty close to the mark.

Footnote

Vance went a step further than Nelle and Truman in putting his subjects at ease. Vance's philosophy was that no one could really study a culture unless you were actually part of the culture itself. He picked up his information informally and most of Vance's informants were not aware that he was collecting folktales.

Vance Randolph

He used the same method.

What adds to the skepticism in Truman's case is not just that In Cold Blood repeats long verbatim passages of dialog, but it repeats long verbatim passages of dialog of which neither Truman nor Nelle were around to hear. Sometimes we even read the characters' thoughts, for crying out loud - including those of the two murderers. Where did Truman get these quotations?

But lest we be blamed as joining in with Truman's Debunkers, remember that in bonafide history books - particularly "popular" histories - it's accepted that reported dialog may not be exactly as spoken. Sources, after all, don't always agree, and authors may combine multiple versions and then recast what was said in a more modern idiom.

For instance, in the story of Richard the Lionhearted, at one point Richard's army is pursuing the troops of King Henry II, who happened to be Richard's dad. As Richard closes in, William Marshall, who stayed loyal to Henry, turns around and with lance lowered, charges. Knowing William's prowess, Richard is alarmed.

In relating the tale, one book quoted Richard as saying "By God's legs, Marshal, do not kill me. I wear no hauberk!" In yet another Richard says, "By the legs of God, Marshal, do not kill me! That would not be right, for I am unarmed". So a later writer pulled the two quotes together as "By God's legs, do not kill me, Marshal. That would be wrong. I am unarmed."

We can't really say the quote is invented. But neither is it exactly what Richard said (particularly since Richard spoke in French). Instead, what we have is a "reconstruction" and - as is often stated - "edited for brevity and clarity".

The point, though, is that such edited, clarified, and reconstructed quotes are common and accepted in writing history, particularly those written for popular consumption. And In Cold Blood was certainly written for popular consumption.

Discriminating Discrepancies

It's also wrong - to quote Richard - to think all discrepancies are Truman's errors. Memories fade and even direct participants don't get things right all the time.

There are even cases where it's not easy to tell who made what error. Or if there was any error at all.

For instance, Truman reports that Perry had steadfastly refused to talk when he and Dick were still in the Las Vegas jail. But during the drive to Kansas, the lead investigator of the KBI, Alvin Dewey, made an off-hand comment which made Perry realize that Dick had indeed "let fly" and "dropped his guts all over the [gol-durn] floor." As Truman wrote it:

To Dewey's surprise, the prisoner gasps. He twists around in his seat until he can see, through the rear window, the motorcade's second car, see inside it: "The tough boy!" Turning back, he stares at the dark streak of desert highway. "I thought it was a stunt. I didn't believe you. That Dick let fly."

However, in 1984, twenty-five years after the crime, Al Dewey coauthored an article about the case. Al said that once Hickock confessed he told Perry about it. But after some skepticism, Perry soon admitted he was guilty. All this happened while they were still in Las Vegas. Perry then gave the details during the car ride back to Kansas.

Now one rule for historians is that an account by an actual participant carries more weight than one by someone who wasn't there. So by all the rules of historical research, we should believe Al's story and not Truman's.

However, in one of the appellate filings, we read that, yes, Dick confessed in Las Vegas. The document also states that Perry gave no information while in Vegas and refused to admit anything even after he was told Dick had confessed.

But - and here we quote the document - "During the trip [emphasis added] Smith admitted his part in the robbery and murders and gave a full account of how the crimes had been accomplished."

Exactly what Truman told us!

So with an official document supporting Truman, we should now believe him!

Correct?

Weeeheeeellllll, not necessarily. Even official supporting documents aren't always correct. And if you turn to the earliest record - the actual trial transcript - we get a bit more complex story.

Regarding the trip back to Kansas, Al Dewey testified (edited for brevity and clarity):

Perry said to us, he says, "Isn't he a tough guy?" meaning Hickock. He says, "Look at him talk." He said, "Hickock had told me that if we were ever caught that we weren't going to say a word but there he is, just talking his head off." He then asked me what Hickock said in regard to the killing of the Clutter family, who killed them. I told Perry that Hickock says that he killed all of the family. Perry told me that wasn't correct, but he said, "I killed two of them and Hickock killed two of them."

[As an aside, note that Al under oath is quoting by memory. But no one criticizes Al. More on that later.]

So we see here that Perry seems to have already acknowledged his guilt before the trip to Garden City.

But now go back to when everyone was still in Las Vegas. Al told of the earlier conversation with Perry.

I told Perry Smith that Hickock had given the other agents a statement and that Hickock had said that they had sold the radio, the portable radio, that they had taken from Kenyon Clutter's room, that they had sold it in Mexico City. ... [KBI Detective] Mr. [Harold] Nye told Perry Smith where Hickock had said that he sold the portable radio, and Smith said that was right.

What we have here is that in Las Vegas Perry acknowledged that he and Dick had disposed of some of the Clutter's property. That is, Perry admitted complicity in the crime but did not actually confess to murder. That he did on the trip to Kansas.

But there is a big take-home lesson in this rather lengthy and convoluted exercise. Despite Truman's claims of absolute fidelity of the quotes and the scenes, he would modify details and make up dialog for a more dramatic telling. Perry did not gasp and twist around in his seat until he could see through the rear window to the motorcade's second car. Before the ride to Kansas, Perry already knew that Dick had "let fly" and besides, the car with Dick was in front.

Nondum Matura Est, Nolo Acerbam Sumere

Adding to the confusion is that some critics have changed their opinions regarding Truman's accuracy. At times we suspect these tempered memories sometimes resulted from tasting a sour grape or two.

For instance, when one of the detectives (not Al Dewey) read the first excerpt published in the New Yorker, he was complimentary. "The old boy has really got something here," he said.

But years later - after Truman was rich and famous and the subject of much celebration - the same detective dismissed passages where he appeared. "I was under the impression that the book was going to be factual," he said, "and it was not. It was a fiction book."

Sour grapes? Well, here not necessarily.

Perhaps it was simply that Truman got it right in some places and not in others. The first installment of the book dealt mainly with the Clutter Family and the discovery of the crime. So the detective may have read the first part as agreeing with the facts. Details of the actual investigation where he was featured more prominently weren't published until the second installment in The New Yorker.

And yes, even Truman admitted he would - well - "edit" things a bit. During his research, he interviewed the schoolteacher who was with the sheriff when they found the murdered family:

Well, I simply set that into the book as a straight, complete interview - though it was, in fact, done several times: each time there'd be some little thing which I would add or change. But I hardly interfered at all. A light editing job.

But what was it Truman edited - several times and yet he "hardly interfered at all"? Was it simply removing the "uhs", "ums", and "ahs" and cleaning up a sentence fragment or misspoken phrases (all common interviewer's courtesies)? Was he only omitting certain passages for brevity and clarity? We don't know, and in fairness to Truman we have to point out that the teacher himself stated that although Truman didn't take notes, he remembered Truman was quoting him word for word.

Well, we also saw that when recounting Perry's confession Truman would rewrite scenes in an "imaginative" way which can't be waved away as "hardly interfering" or "light editing". But his fans will say that Truman did not materially change the gist of what happened. Such minor changes can be accepted as a minor literary peccadillo.

Unfortunately, it has been found that Truman stretched the factual boundaries a bit further than journalists would think proper. Remember that Floyd Wells, Dick's former cellmate, was the one who tipped off the authorities. He was, we read, laying in his cell bunk and listening to the radio when he heard a broadcast about the murders.

After some hesitation, Floyd informed the prison warden, Tracy Hand, about his and Dick's conversations. Warden Hand quickly called Logan Sanford, the Director of the Kansas Bureau of Investigation, who immediately informed Al Dewey of the new development.

According to Truman, Al then went home that night and told his wife about the new information. Marie expressed caution about what Dick called "a convict's tattle", but Al was optimistic the men were the guilty ones.

Then that same day (again we read) another detective, Harold Nye (later director of the KBI), had been dispatched to visit the Hickock farm in Edgerton, about 15 miles southwest of Olathe. Dick's mother and father received him courteously since he told them that he was investigating Dick's parole violations and passing bad checks - not investigating whether their son murdered a family.

From Mr. Hickock, Harold learned that after his release from prison, Dick lived at home and was working at a local auto repair shop. He had not traveled anywhere - except for one weekend.

Mr. Hickock told Harold that Dick and his friend Perry Smith had driven to Fort Scott - about an hour's drive from Edgerton - where Perry's sister was holding some money for him. Harold casually asked for details of the trip, and Mr. Hickock said they left the afternoon of November 14. They stayed away overnight and Dick arrived back on the farm about noon on November 15.

So within 24 hours of Floyd spilling the beans to Warden Hand, the KBI had strong circumstantial evidence that Dick and Perry were indeed the criminals.

Here the debunkers step in. They say that KBI documents show that Al believed that the killer was someone local and with a grudge against the Clutters. So he had discounted the "convicts tattle" and waited five days before finally following up Floyd's tip.

One thing that you have to watch for in writing history is making things nice and simple when they are really complex and confusing. And Floyd's information was complex and confusing.

Remember Floyd heard the news in a radio broadcast on November 17, 1959. He said nothing until early December, and the first KBI report that mentioned Floyd's story was written down by KBI Agent Wayne Owens on December 5. There was a follow up report on the 10th. Clearly the KBI realized the potential value of Floyd's testimony as soon as he spilled the beans:

As Agent Owens wrote:

Now [Floyd] says if it comes to a show down that he will be glad to make a witness and testify to what HICKOCK told him in case HICKOCK is ever a defendant in any action that might be taken in regard to this case.

Wayne's interview seems to counter the argument that the KBI dismissed Floyd's information. And Al Dewey's son has said that documents in his possession also show that the KBI took Floyd's information seriously and followed it up promptly. Of course, hindsight is 20/20 and in the real world, Floyd's was one tip out of many and each had to be sifted through and followed up.

But it is true that Truman again used a novelistic technique of "compressing the action". Harold visited the Hickock farm five days after Floyd spoke to Warden Hand, not the same day. He did so not alone but with other officers. Nor did they disguise the purpose of their visit, and when they left they took Dick's shotgun and a hunting knife.

Critics have suggested another motive for Truman's "compressing the action". Novels need a hero, and Truman picked Al Dewey, who was after all the lead investigator of the case. Truman's writing of a stalwart lawman who would immediately pick the right tip out of many certainly irritated others involved in the case, some who in later years downplayed Al's part. But we also suspect by then the grapes had indeed turned sour.

Evidentially, My Dear Truman

Literary courtesy mandates we cut Truman some slack. There's nothing easier than finding discrepancies while sifting through the raw information provided by multiple informants. So it's easy to cast doubt on virtually anything that you read.

One of the novel's most tense scenes - which was also in the 1967 movie - is about an executive from Omaha whom Truman called Mr. Bell and who gave Dick and Perry a ride. Dick and Perry planned to kill Mr. Bell and take his car. But just as Perry, sitting in the back seat and on cue from Dick, was about to bash Mr. Bell on the head, Mr. Bell suddenly braked the car to pick up another hitchhiker.

Truman said he managed to confirm the story by visiting Mr. Bell at the company's headquarters. Dick had Mr. Bell's business card and so Truman got his address.

Mr. Bell was quite surprised when a perfect stranger arrived at the plant and showed him the photographs of the two hitchhikers. But he wasn't nearly as surprised as when Truman told him who the two young men were and how closely he, Mr. Bell, had nearly fit into their plans.

Here if you wish, you can debunk. Dick and Perry had wandered around the country, been arrested in Las Vegas, driven to Kansas, and had gone on trial. Any items in Dick's possession would have been taken from him and held by the police.

Next, would any of these items have been handed over to a writer covering the story? Then if we move forward to include the time of their removal to the Kansas State Penitentiary and Truman was finally allowed to visit them in prison, are we to believe that Dick still had Mr. Bell's business card?

Few people have questioned the story of Mr. Bell's hairbreadth escape. But there are questions. Dick steadfastly maintained that he did not and never had any intention of killing the Clutters. And all the time Truman was writing In Cold Blood, Dick and Perry were appealing their case.

So why would Dick or Perry tell Truman - or anyone - that they almost committed yet another murder? As before, the more you delve into the crafting of In Cold Blood, there's more questions you can craft about Truman's crafting.

Particularly since there's one scene that Truman did craft.

At the end of the book, Truman returns to a peaceful scene in Garden City's Valley View Cemetery. As Al Dewey visits the grave of the Clutter family, he sees a young college student who had been a friend of Nancy. After a brief conversation, the two-part company, and the novel ends.

It's an effective ending for the novel. But it never happened. The scene was complete fiction.

The Documentable Truman Capote

Truman got much of his information from the trial transcripts and other documents. That he corresponded with many of the participants, including Dick Hickock and Perry Smith, is not to be denied.

Truman said that during "all those years", he wrote to Dick and Perry twice a week. He also said they wrote to him twice a week. Strictly speaking, then, Truman is saying that from April 1960 to April 1965, he sent Dick and Perry five hundred letters each and he got five hundred from each in return.

What, we wonder, became of such valuable source material?

If Dick and Perry kept Truman's letters, then they would have been in their personal belongings. Dick's effects would have been sent to his mother, who lived until 1989.

But Perry, although his father lived until 1986, asked that all of his belongings be sent to Truman. These were, according to one article, contained in "two huge boxes of letters, songs, and books.

And Truman confirmed he received Perry's things. As he said:

I have some of the personal belongings - all of Perry's because he left me everything he owned ...

Was it two huge boxes (crates, maybe)? Well, according to Truman:

It was miserably little, his books, written in and annotated; the letters he received while in prison ... not very many ... [Truman's ellipses]."

Ha? (To quote Shakespeare.)

The contents were

MISERABLY LITTLE?

MISERABLY LITTLE?

And the letters were

NOT VERY MANY?

NOT VERY MANY?

But what about those

TWO HUGE BOXES?

TWO HUGE BOXES?

And those  FIVE HUNDRED LETTERS?

FIVE HUNDRED LETTERS?

The trouble is there's not much we find about extensive correspondence either way. Truman did mention Perry sent him a long letter - 100 pages - which ended with a quote from Thoreau. Truman also said that Dick sent him a long letter. But it was asking for a critique of arguments for his appeal. And in a published selection of Truman's letters - admittedly by no means comprehensive - there are only three letters from Truman to Perry. They are brief and composed of only a few lines.

There is also a film clip of Truman looking through some of Dick and Perry's letters. Unfortunately, the cropping of the frame blocks out the size of the pile. But it's scarcely a thousand letters.

OK. Where are the letters now?

Truman left many of his papers to two public institutions, the Library of Congress and the New York Public Library. And those august institutions do give a summary of the materials in the collection.

And the Library of Congress tells us they hold:

Chiefly literary manuscripts including drafts and manuscripts of prose fiction, dramas, and screenplays as well as journals, notebooks, and other writings. Includes drafts of Capote's novels, Other Voices, Other Rooms (1948), Breakfast at Tiffany's: A Short Novel and Three Stories (1958), and In Cold Blood: A True Account of a Multiple Murder and Its Consequences (1965); the musical play, "House of Flowers" (1954); the short story, "A Christmas Memory" (1956); and a profile of Marlon Brando, "The Duke in His Domain" (1957).

Certainly not much there regarding a thousand letters from two convicted murderers.

Well, what about the New York Public Library?

At last. Now we're told there is a holding of Truman's correspondence - and particularly letters related to In Cold Blood. As the NYPL states:

The bulk of the correspondence consists of letters and postcards from Capote to Andrew Lyndon and to Alvin Dewey and Marie Dewey ... Other correspondents include Jack Dunphy, Leo Lerman, Donald Windham, Cecil Beaton, John O'Shea, Joseph Fox, Irving Lazar, Alan Schwartz and family members.

Ha? (Again we quote Bill.)

But what about letters from Dick and Perry?

Just where the hey are those thousand letters from Dick and Perry?????!!!!!!??????

Just where the hey are those thousand letters from Dick and Perry?????!!!!!!??????

That Truman was allowed regular correspondence with Dick and Perry is not in dispute. But we'll also find that examining proof of the regular correspondence (again) raises a lot of questions and provides few answers.

The Garrulous Truman Capote

Truman Capote

Before

Before

(In Kansas)

Well, if the massive Truman/Dick/Perry correspondence seems elusive, what about those extensive interviews with Truman and Perry and Dick that everyone talks about?

We know for sure that Truman spoke to Dick and Perry. There are a series of photographs of a young and slim Truman talking with Perry in what seems an informal and relaxed conversation. These photographs were taken by famed photographer Richard Avedon who had agreed to accompany his friend to the trial.

There are three time frames when Truman could have visited Dick and Perry. First, they could have met when they were brought back from Las Vegas to Garden City. There Dick and Perry at first refused to meet Truman or Nelle. But later they changed their minds and the first meeting lasted 15 minutes.

Next, during the trial they certainly met as evidenced by the photographs. And of course, they could have met during the five years Dick and Perry were in prison.

OK. We know Truman met with Dick and Perry.

BUT HOW OFTEN???!!!???

BUT HOW OFTEN???!!!???

The information we must admit is not completely consistent. One article says that Truman claimed it was over two hundred times. But in a filmed interview, he said that he visited them in prison about once every three months. We're talking about maybe twenty meetings apiece. So just when did Truman cram in the remaining one hundred and sixty interviews?

Dick and Perry arrived in Garden City, Kansas, on January 6, 1960, after being driven from Las Vegas. Truman's major biographer then tells us that in mid-January Truman and Nelle returned to New York and then returned for the trial.

In other words, after Dick and Perry arrived in Kansas, Truman and Nelle remained in Garden City a bit longer than a week.

Not many interviews there.

The trial lasted from March 22 to March 29. Dick and Perry were sentenced on April 4, 1960. They arrived at the prison in Lansing the next day, April 5.

So from the time of the trial to when Dick and Perry arrived at the prison, there was a total of 14 days for Truman to cram in his interviews.

Not a whole lot there, either.

But as we'll see, Dick did speak to reporters during the trial. His purpose, though, was to try and exonerate himself and since Truman wasn't writing anything at that time, speaking to Truman wouldn't have been of much point.

And according to Truman, Perry was held in the area normally reserved for women prisoners. The cell was attached to the kitchen of the living quarters of the undersheriff, Wendle Meier, and his wife, Josephine.

According to Truman, unless Josie was working in the kitchen, Perry spent virtually all of his time alone. Truman mentions visits from Perry's attorney, from Al Dewey, and from an old friend from the army who came as a character witness - but no visits from journalists or writers. True, Truman could have simply left out his own visits - in the nonfiction novel, he said the reporters should not be part of the story - but there's no hint of extensive interviews.

Instead if you read In Cold Blood, we find Truman spoke with Josie Meier. He also spoke and wrote to Donald Cullivan, Perry's friend from the army. Don had agreed to appear as a character witness and sat with Perry during the trial. He also visited Perry in his cell.

It's also clear from In Cold Blood that Truman had access to Perry's diary. This was presumably in the box of the "miserably little" possessions that Perry had sent to Truman or perhaps Perry had sent it to Don. But it's difficult to document any visits from Truman during this time.

Pooh! say Truman's fans. All this is contra-Capote claptrap. We're not saying Truman had hundreds of interviews in the three months that Dick and Perry were in the Garden City jail. But remember that Dick and Perry spent five years in prison while their case was being appealed. That certainly gave them plenty of time for the extensive interviews.

True, Truman got permission to visit Dick and Perry - but not without a struggle. When he first contacted the prison authorities he encountered, figuratively as well as literally, a stone wall.

The warden said that prison rules were clear. Family members were permitted visits; no one else. Only if the inmates had no family could they meet and correspond with friends.

Both Perry and Dick had living relatives. Perry's father had written to ask if he could come and visit (although he never did). Dick's mother also lived not far from the prison and Truman said she visited once a month.

But ... and it's a big "but".

Prison records specifically list Truman as a regular visitor and correspondent for both Dick and Perry. There is even a letter where Truman tells the warden he will stop by to visit. He says not to bother to answer the letter as he will telephone. It's almost like Truman was a privileged guest.

So we must suppose that the extended quotes of Perry and Dick the details of their wanderings, the people they met, their conversations, their musings and thoughts, and their time in prison. The stories Dick told - including a detailed description of the execution of Lowell Lee Andrews, who as an 18 year old college student had murdered his entire family - must have come from those visits.

All right, already! We said we know Truman met with Dick and Perry.

BUT, DANG IT! HOW OFTEN???!!!???

BUT, DANG IT! HOW OFTEN???!!!???

The inmate files contain a list of the approved correspondents and visitors. If correspondents wrote frequently - as Dick's mother did - they were simply designated as "regular". If they were approved but not regular, they were listed as "irregular".

And visitors?

Sometimes they were also designated as regular. But often there was an actual number recorded. Visits, of course, were less frequent than letters and it was easier to keep tabs of them.

And how many times did Truman visit Perry? Well, let's look at the record (Note: Addresses are blanked out because some are still extant, and the explanatory brackets and indicators are not in the original document).

| CORRESPONDENTS - VISITORS (Indicate Regular or Irregular) | ||||

| Name | Address | Send | Receive | Visits |

| Tex. J. Smith [Father] | XXX XXX, XXXXXXXX, XXXXXX | Reg | Irr | None |

| Nelle Harper Lee | XXX XXXX XXXX XX XXX XXX XXXX | Irr | Irr | Two |

| Donald E. Cullivan [Army Friend] | XXXXXXXX XXX XXXX XXX XXXX XXXX | Irr | Irr | None |

| Mitchell Jones [Psychiatrist Hired by Defense] | XXXX XXXXX XXXXX XXXXXXX XXXXXX | Irr | Irr | Three |

| Truman Capote | XX XXXXXX XXXX XXXXXXXX XXX XXXXX | Reg | Reg |  Three Three |

| Josephine D. Meier [Wife of Finney County Undersheriff, Wendle Meier] | XXXX XX XXX XXXX XXXXXX XXXXX XXXX | Irr | Irr | None |

| Wendly [sic; Wendle] Frank Meier [Finney County Undersheriff] | XXXX XX XXX XXXX XXXXXX XXXXX XXXX XXXX | Irr | Irr | None |

| Several visits from Attorneys. | ||||

| THIS FINAL REPORT PREPARED BY: | D. L. Fredeon [signed], Classif. Officer | |||

| Date: 4/14/65 | ||||

Ha? (We keep quoting William.) Truman only visited Perry three times?

¡No es possible!

Hold on, though. Perhaps this is where the taciturnity of prison records plays havoc. We see the number of visits are listed. But perhaps these are visits per unit time - probably per year. If so then Truman's statement he visited them "about" every three months wouldn't be so far off.

Well, before we come to conclusions, erroneous or otherwise, it's worth looking at Dick's correspondence and visitors list.

| CORRESPONDENTS - VISITORS (Indicate Regular or Irregular) | ||||

| Name | Address | Send | Receive | Visits |

| Walter D. Hickock [Brother] | XXX XXX, XXXXXXXX, XXXXXX | Reg | Reg | Reg |

| Paul Hefley | XXX XXX, XXXXXXXX, XXXXXX | Reg | Reg | None |

| Leslie Rodes | XXXXXXXX XXX XXXX XXX XXXX XXXX | Reg | Reg | Reg |

| Kirk Merillatt | XXXX XXXXX XXXXX XXXXXXX XXXXXX | Reg | Reg | Reg |

| Eunice Hickock [Mother] | XXXX XXXXX XXXXX XXXXXXX XXXXXX | Reg | Reg | Reg |

| Nelle Harper Lee | XX XXXXXX XXXX XXXXXXXX XXX XXXXX | Reg | Reg | None |

| Francis Boyd Oshal [sic] | XX XXXXXX XXXX XXXXXXXX XXX XXXXX | Reg | Reg | None |

| Truman Capote | XX XXXXXX XXXX XXXXXXXX XXX XXXXX | Reg | Reg |  None None |

| THIS FINAL REPORT PREPARED BY: | Ben A. Dawes [signed], Classification Officer | |||

| Date: 4/14/65 | ||||

So there in black and pale cool brown (the paper wasn't white) we can start to figure things out.

First despite what the prison administrators originally told Truman, it is clear visitors other than blood relatives were permitted. What's curious is that the psychiatrist who was hired by the defense, although a regular visitor and correspondent for Perry, isn't listed for Dick.

Truman mentioned that Mrs. Hickcock visited her son once a month, traveling to the prison by bus. However, Dick's father had died three months after the trial, and the list indicates she was probably driven by a family friend in whose home she was residing (the addresses were the same). Dick's brother, Walter, and others are simply listed as "regular" visitors without any specific number of visits.

But we know the list is not just the number of visits permitted, total or per unit of time. That's because Perry's father would also have been allowed regular visits as well. And yet, the number of his visits is listed as "None". And indeed Tex Smith never visited his son.

And finally take a look at the notation and date at the bottom of the page. The file was prepared on April 14, 1965. This is the date of the FINAL report and is the day that Perry and Dick were "released" from prison to use the files' rather oblique terminology.

The conclusion, then, is - at least if we go by the prison records - that Truman visited Perry three times in five years.

And from Dick's record, the number of times Truman visited him is:

NONE!

NONE!

Yep, in five years, the records state Truman did not visit Dick a-tall.

All right, then. How do we reconcile the apparent paucity of visitations with people who knew Truman personally and who said he did visit both Perry and Dick?

Well, those who said so may have thought that whenever Truman went to the prison, if he visited Perry then he also visited Dick. And given the hint that the rules were not as rigid as supposed, it is certainly possible that the authorities would allow Truman to slip in a few extra visits beyond those scheduled.

But in any case, the record does not support Truman's claim that there was a visit every three months, much less the reported two hundred get-togethers in all.

The Many Tales of Richard Eugene Hickock

So if we go by the record once Dick and Perry were in prison, they met with Truman only a few times. Officially Truman never met with Dick at all.

But what could have kept Truman away, particularly from the garrulous, talkative Dick? Well, we now turn to a part of the story that only recently re-emerged to the public's attention.

What wasn't known for years is that Dick had been writing his own book. There was even a title: High Road to Hell.

Dick, it seems, had struck an exclusive deal with Kansas journalist, Mack Nations. Dick would provide details of his story to Mack who would do the actual writing and get the book published.

Here is a real discrepancy. Mack was not on Dick's list of correspondents and in a letter to Warden Tracy Hand, Mack mentions how he is permitted neither visits nor correspondence with Dick.

But there are letters from Dick to Mack on file at the Kansas State Historical Society. The inventory also lists a CD with copies of Dick's letters.

However, no book deal materialized (Random House returned the manuscript saying they had already contracted Truman). So Dick began telling his story in an abbreviated form in the December 1961 issue of Male - one of the "men's magazines" that proliferated the supermarket and drug stores from the 1920's to the 1970's. Officially the story was under Dick's by-line but the actual writing was by Mack.

Truman was considerably irritated when he learned of the potential competition. This is certainly a possible cause for his avoiding Dick.

On the other hand, when Mack learned Dick was corresponding and (possibly) meeting with Truman he was also irate - less at Truman than at Dick. He wrote to Warden Hand to remind Dick that they had an exclusive deal. By telling his story to another writer, Dick was forfeiting any right to payment for his story.

But what raises eyebrows is not the manner of Dick's story but its matter. If we believe Dick, there seems to have been a far more conspiratorial motive than simply a robbery of a safe.

After Dick and Perry entered the house, Dick begins to ruminate. After the "score" he says he's going to meet someone named Roberts.

I was going to kill a person. Maybe more than one. Could I do it? Maybe I'll back out. But I can't back out, I've taken the money. I've spent some of it. Besides, I thought, I know too much ... It was almost two o'clock and our meeting with Roberts was about an hour away. We didn't want to miss that. Five thousand bucks is a lot of dough.

Who was this "Roberts"? Was he bankrolling the job?

Were the Clutter murders actually a contract killing?

Certainly according to Dick, "Roberts" was well acquainted with the Clutter home:

Just like the diagram Roberts had given me showed, a hallway led off to the left.

And after they found Mr. Clutter (he slept in a bedroom on the first floor), Dick added:

We escorted Clutter into the west room, and figured we just as well get all we can. Besides, we had to make it look like a robbery.

Yes, "they" had to make it look like a robbery.

Naturally, there are skeptics of this new theory. For one thing, for all the talk about "Roberts", Dick clearly believed there was a safe. If "Roberts" knew the Clutters so well as to provide a detailed map of the house, he would have known there was no safe and that Mr. Clutter never used cash.

That the Clutter murders was a "hit" is an intriguing theory, yes. But a simple explanation is the "Roberts" story is complete hokum invented by Dick Hickock, who was among other things was an experienced con man.

A little thought lets us realize this is a real possibility.

For one thing just what kind diagram would they really need for the house?

Dick and Perry arrived at a house that was never locked. And they believed there was a home office with the safe. But which door?

Not the front - which would lead to the living room. Not the back - every backdoor in Kansas led to the kitchen. That left the side door which was in fact that of the office.

There they looked around and soon found Mr. Clutter who slept in a room next to the office. Why would they need a map of the house? They could ask Mr. Clutter where everything was.

And that's exactly what Perry said they did. As he said:

I pointed upstairs and asked who was up there. He said his wife and children were up there.

And what kind of directions do you need to get to River Valley Farm? After all, once you're in Holcomb just:

- Drive south on Main Street and two blocks past the railroad tracks.

- Turn right

The road runs right to the Clutter's tree-lined driveway.

So all Dick needed was a few words from Floyd and a road map.

By far the biggest argument against the "hit" theory is Dick and Perry could have - and surely would have - turned state's evidence on the "brains" behind the crime. And the KBI would have been perfectly happy if this was what happened. The earliest theory of the KBI - held by virtually everyone - was the Clutter murders were some kind of grudge killing. But in the legal documents of the trial and five years of appeals, there's no mention of a motive other than the robbery.

There is another explanation for the identity of the mysterious Roberts. In many non-fiction books names are sometimes changed for the characters who are still alive. Roberts could very well have been a pseudonym.

And yes, there was someone who Dick claimed had provided him with directions to the Clutter's farm, a diagram of the house, and to whom Dick had promised a "cut" of the money. That it was none other than William Floyd Wells.

A Snitch in Crime Serves Time

The greatest irony of the case is that Floyd Wells - whose (false) story about Herb Clutter having a money-stuffed safe led to the murders - received a $1000 reward and a parole. Dick reportedly made a discourteous remark at the time. As he put it:

"Sonofa[gun]. Anybody ought to hang, he ought to hang. Look at him. Gonna walk out of here and get that money and go scot-free."

That's exactly what happened.

Some, though, have said that Floyd should have been charged as an accessory to the crime. After all he told Dick about the safe.

Of course according to In Cold Blood, Floyd did not spontaneously volunteer the information about Herb Clutter keeping a safe. He told Dick about it only after Dick asked. And Floyd did warn Dick he could never get away with it and thought Dick was just blowing hot air.

There are major differences between Truman's account and Floyd's own words. When Floyd spoke to Detective Owens, he explained how the whole thing started:

After entering Kansas State [Penitentiary] I "celled" with Dick Hickock. Hickock said he liked western Kansas and maybe would try to get a job with the Clutters. I described the location of the house. I suspect I talked too much about the money Mr. Clutter had. Hickock talked a lot about Perry Smith. Said after they got out of the 'joint' they could pull some jobs to get enough money for a down payment on a boat. They would run a charter service for deep-sea fishermen and eventually make contacts and use the boat to bring in narcotics. I didn't believe Hickock but he kept talking about it. I tried to talk him out of it, said he would get caught. But he said he had a plan, and, after the robbery would kill everyone there and leave no witnesses.

Here, then, is Floyd at his inconsistent worst. On the one hand, he said that Dick was going to rob the Clutters. Then he told the same KBI agent that Dick just wanted to get a job with Mr. Clutter.

As far as his criminal plans, in this last telling, Dick said he was going to start a charter boat service as a front for drug running. For their capital, he and Perry would pull "some jobs" and leave no witnesses.

But was Dick specifically talking about robbing the Clutters? Here it seems more like Floyd was saying that Dick was only talking about a general modus of a criminal enterprise and not a specific crime.

If we accept this scenario, then the reason Floyd didn't warn anyone about danger to the Clutters is he had no idea that Dick was specifically targeting the family. But when he heard the radio broadcast, he realized that Dick had made the Clutters one of the "jobs".

If that is indeed what happened, Floyd was not an accessory.

However, note that Floyd did talk about THE robbery. Dick and Perry would kill everyone there and leave no witnesses. That sounds more like he had one major job in mind. In his deposition to Wayne, Floyd had quoted Dick as saying:

As soon as I get out on parole, [Dick said], I'm going to find me some transportation, get ahold of Smith and go to the Clutters and see if there's still $10,000 in their ------ safe.

This contradicts Floyd's claim that Dick was going to work for the Clutters because he liked western Kansas. But note that even here Floyd did not say Dick would kill the Clutters.

By the time he got to trial, though, Floyd had cleared the discrepancies - sort of. He said at first Dick talked about working for Mr. Clutter and later decided to make robbing the Clutters one of his "jobs".

But Floyd Wells was clear about the safe. Mr. Clutter had one. As Wayne wrote in a clarifying memo Floyd was certain that Mr. Clutter had a safe for keeping large amounts of cash:

... [Floyd] said it was a real safe; it was big, black, heavy and it had a dial on it and that it wasn't just a metal strongbox locked with a key like valuable papers are kept in just for fire protection.

Floyd didn't back down, no matter how much Wayne grilled him. By golly, Mr. Clutter had a safe, no ifs, ands, or buts.

But in In Cold Blood Floyd was not so definite. He said he thought there was a safe. "I knew there was a cabinet of some kind."

Yes, Floyd contradicted Truman. But we see Floyd also contradicted Floyd.

Now let's move on to 1960. Perry and Dick were on trial and Floyd was called to testify that he told Dick about the safe.

At one point, Floyd spoke with a reporter of the Hutchinson [Kansas] News. Now we read:

Wells said he told Hickock that the Clutters had a safe when he worked for the family [ca. 1948-1949], but they were building a new home when he left their employ. He said he told Hickock that he knew of no safe in the new home. He said that he knew nothing at all about the new home.

Safe? What safe?

Floyd, like Sergeant Schultz, knew no-THING.

Well, well, well. (Or is it Wells, Wells, Wells?) At best, Floyd is remarkably inconsistent with his story shifting over time. At worst, it looks like you couldn't believe a word he said.

But don't despair! There's yet another version of what went on during this most infamous of prison cell bull-sessions. That's Dick's own story. As you can guess, he paints a slightly different picture from what either Floyd or Truman said.

Far from wanting to make a big score, Dick's plan was to go straight. He was sick of doing time, he said, and he had legitimate employment lined up.

But as far as what Floyd's plans were, Dick was adamant. In his telling (edited here for brevity and clarity):

[Floyd] told me that if he was getting out the first thing he would do, would be to take a little drive and pull the sweetest score he ever seen.

He went on to elaborate how he worked for Clutter and had worked for him several months. During this time of his employment, Clutter built a new home, and had installed a wall safe. He kept five thousand all year and as much as ten thousand at harvest time.

Dick kept explaining:

I made up my mind not to go for it, but ... he would set me up on it, if I promised to send him a thousand bucks for doing it ... I told him, "If I pull it, I'll send you a grand."

I took the diagrams [!] and studied them. I asked Wells how the safe was anchored in the wall. He said he worked for Clutter when the house was built, and watched the safe installed.

Ha! So it was Floyd who was going to get out and make the "score" at the Clutter farm. And the safe was so in the new home, and the diagrams were provided by Floyd Wells.

And yet. Even after hearing about the money and the Clutters, Dick was still wanting to abjure his life of error. He continued the story:

But before I left for home I told him, "If things don't go right for me in the free world and I ever decide to knock off this safe, I'll send you a grand." ... And we shook hands on it.

OK. According to Dick, the whole plan was Floyd's. Dick had no plans to rob the Clutters unless he had trouble going straight.

There are, obviously, questions.

For one thing, which of these two career criminals and habitual convicts do you want to believe?

Next, why would Floyd bring Dick in on his plans at all? If Floyd pulled the job himself, he'd get $5000 or maybe $10,000. With Dick in the plan, he'd get only $1000.

Finally, once Floyd learned Dick had gone through with the plan, why would he turn Dick in? If the burglary was successful, he'd get his $1000. But if he squealed on Dick, Dick would turn state's evidence and accuse Floyd of being the one who planned the whole thing.

You'll notice that even in Dick's telling, the plan was that the crime was to go no further than a burglary. Neither he nor Floyd said they'd leave no witnesses.

It would not be much of a surprise, though, for Floyd to have a change of heart if what was intended to be a simple burglary had turned into a mass murder. Floyd's only way out was for him to spill the beans and make it look like the plan was Dick's.

But the big question is if the plan was Floyd's, why didn't Dick tell this to his attorneys? They should have brought it out at the trial as there are often rules limiting testimony of co-conspirators. There's not a hint in In Cold Blood that Dick claimed Floyd was behind the whole thing.

Maybe not in In Cold Blood, but in the newspaper stories written during the trial Dick sure blabbed about it.

In a statement to the press that was released on March 26, 1960 - the fifth day of the trial - Dick said that Floyd planned the crime and was to get 20%. Since Dick expected to get $5000, that would be $1000 - just as Dick said.

So Dick was telling this story while the trial was in progress!

But why tell the story in a press release? And who did so? Dick's attorney?

Not hardly.

The story was told in a handwritten note - and was released by Dick's mother!

It's most unusual that a defendant would release a statement independent of his attorney. But we also know that in his appeals, Dick was quite critical that his lawyer, Harrison Smith, did not provide adequate counsel. Although you might dismiss such grousing as standard legal rhetoric, from the first it seems that Dick was far from satisfied with Counselor Harrison's advice.

So why wouldn't Harrison let people know that Dick claimed Floyd was the brains behind the crime?

The answer here is pretty straightforward. Without other evidence for Floyd's complicity, Dick would have to take the stand.

And there was a big reason not to.

One thing an attorney hates is when a guilty client wants to testify. After all, a guilty client might lie - which an attorney is not supposed to permit2.

Footnote

A particularly problematical case, given that communications between an attorney and his client are privileged, is if a guilty client wants to testify on his own behalf and tells his lawyer he will lie.

Worse, if a client does testify - and Harrison would have told this to Dick - he'll also be subject to cross-examination. If a client lied in his examination, then he'll most likely lie during the "cross". The questions can also delve into the witness's credibility and honesty, and Dick with a history of larceny and check forging - not to mention his admission he participated in a crime which resulted in the murder of a family of four - would have had trouble convincing the jury of his probity. So Dick shying from taking the stand is understandable.

But what the attorneys could do was to work this theory in when they cross-examined Floyd. There are indications that they leaned toward this approach.

When Perry's attorney, Arthur Fleming, got up, he asked whether Floyd wanted Dick to believe the Clutters had a safe.

| Arthur: | Didn't you mean to convey to [Hickock] the idea that Mr. Clutter had a safe? You wanted Mr. Hickock to believe that, did you not? And you meant for Mr. Hickock to believe that Mr. Clutter had a lot of money, didn't you? |

| Floyd: | I told him Mr. Clutter had a lot of money, yes. |

But neither Arthur nor Harrison specifically asked Floyd if he was the brains behind the crime and how much Dick had promised to pay him. That would likely have sparked an objection from the prosecutor, Duane West, since such questions assumed facts that had not been established by evidence or testified to by the witness. And so Floyd left the stand more or less with his testimony intact.

The Rough Ride of Righteous Richard

The story that Floyd planned the crime wasn't the only statement Dick released to the press sans counsel. Toward the end of the trial, Dick told a reporter that he had wanted to take a lie detector test. But, Dick griped, no one would let him do it.

All along Dick had been insisting Perry and Perry alone had killed the Clutters. Dick believed a polygraph test would clear his name.

But when a reporter asked KBI detective, Roy Church - who actually took down Dick's confession - if Dick had asked for a polygraph test, Roy said, no. Dick's lawyer would have to make the request, and he had not done so. Then when the reporter asked Harrison why he didn't ask for the test, he shrugged that it wouldn't have helped their case.

That's probably true. With few exceptions "lie detector" tests are inadmissible in criminal trials. But the really big "if" is about the test's reliability.

Psychologists tend to pooh-pooh lie detector tests as being only slightly better than chance - maybe 70%. On the other hand, lie detector experts usually maintain that in the hands of a skilled and properly certified technician, the polygraph is at least 90% reliable3.

Footnote

One lie detector expert pointed out the difference in the test's reliability are often due to how the reliability is calculated. The critics inevitably use a method that makes the tests look worse, while the advocates crunch their numbers in a more flattering manner.

For instance, if 10 tests are administered you might have 7 tests correctly identify whether the subject is lying or telling the truth, 1 test may identify an honest subject as deceptive (a false positive), and two tests might be inconclusive.

You can calculate the reliability of the tests in two ways. First you can say that the test was correct only 7 out of 10 times. So you have only

7 ÷ 10 = 0.7

... or 70% reliability. Better than chance, yes, but not that impressive, the critics say.

Or you can ignore the "inconclusive tests". Then you point out the test was "right" 7 out of 8 times. Or:

7 ÷ 8 = 0.875

Or 87.5 % which you can round up an boast of "nearly" 90% reliability.

The National Academy of Science has reviewed reliability of the polygraph. They concluded, yes, the polygraph detects deception significantly greater than chance. But it is also, they say, a test far from perfect. False positives are a particular problem and honest people might be identified as telling lies. The guilty can also slip through. One of the most famous real world spies, Aldrich Ames, an American CIA agent, passed two lie detector tests while he was selling secrets to the Russians.

The problem is that it's hard to test a lie detector under realistic conditions. The theory behind the machine is that certain physiological responses are indicative of deception. But if you have voluntary subjects participating in a controlled laboratory test, then lying has no particular significance. So the physiological responses would not be expected to be the same as those of a "real world" subject whose lying would result in dire consequences.

But uno momento, señors y señoras. Dick was volunteering to take the polygraph test. Since he felt he could pass, isn't that in itself evidence that he would tell the truth - and so supports his story that he did not kill any of the Clutters?

Possibly. In fact, one of the reasons investigators ask a suspect to take a lie detector tests is to see if they will refuse. And if someone insists on taking the test - as Dick did - they will be inclined to see the subject as truthful. But then someone like Dick - a cocky lying con man when at his best behavior - is exactly the type of person who would think he could "beat the machine".

We wonder, though. Dick really did seem bitter that he was being convicted - not of robbing the Clutters - but for killing them. During his confession, Dick told Detective Harold Nye that there was never a plan to kill anyone:

| Harold: | But there wasn't to be any killing at that time [when Dick and Perry arrived at the Clutters home]? |

| Dick: | That's for ---- sure. There was supposed to be none at no time. |

Although Dick didn't think he'd get off scott free, he clearly believed he shouldn't get the supreme penalty for something Perry did.

| Dick: | [Perry]'ll probably deny shooting them. ... ------ if I get the rope and he doesn't. |

An even more serious allegation Dick told at the time of the trial was that the KBI agents had used third degree tactics to coerce his confession.

Dick told this story in an "exclusive interview". It was granted - not to Truman - but to a reporter from the Topeka Daily Capital, Ron Kull.

Dick vouched that not only had two KBI agents perjured themselves on the stand, but that to get him to confess they whipped him on the head for an hour with their fists and blackjacks. Dick said he passed out after the confession.

If this was true, then why didn't Dick recant his confession during the trial? Forced confessions are absolutely inadmissible and if physical brutality is used, the questioners themselves can be prosecuted.

For one thing, once a confession is given it is extremely difficult to get it thrown out. Even if a defendant recants, the confession will likely still be admitted in evidence unless there is strong evidence for coercion.

But coercion is difficult to prove. And in Dick's case there is strong evidence that the confession was in fact completely and entirely voluntary.

Although Dick really did pass out in the hallway after giving his confession4 the recording of his confession pretty much refutes this being because of the tactics of the questioners.

Footnote

Dick did state that he wasn't sure if he passed out because of the alleged mistreatment, though.

Far from Dick's confession being forced, it was even taken with proper caution for preserving his civil rights. Although Dick and Perry were arrested before the famous Miranda ruling, the KBI agents were careful to advise both men that they were under no obligation to answer any questions, that what they said could be used against them, and that they were entitled to a lawyer at all times.

Of course, when they first waived any request for a lawyer, Dick and Perry thought they were being accused of nothing worse than parole violations and passing bad checks - not that they were murder suspects. But even when Dick confessed, the recorded confession shows no hint of any "blackjacks" or knocking him about the head. Instead Detective Harold Nye spoke quietly and matter of factly. And he reminded Dick that what he said could be used in court.

| Harold: | You understand that this can be used against you? |

| Dick: | Yes. |

Then Dick returned to the topic that was continually on his mind:

| Dick: | Is there anyway I can get out on a manslaughter charge because I never pulled a trigger. |

Harold again responded calmly.

| Harold: | Of course that would have to be worked out with the County Attorney, Dick. I couldn't tell you that. |

Here KBI Agent Roy Church added.

| Roy: | You do whatever you want to. That's just a suggestion. |

Sorry, Dick. That's scarcely a "third degree" interrogation.

But probably the major reason Harrison didn't want Dick to testify is that Dick - like Floyd - told a rather meandering tale.

For instance, at one point Dick said that he had no idea "what happened" until it was too late. When he and Perry were in the room after Mr. Clutter had been tied and gagged. Dick then said:

| Dick: | In fact I never knew what the ------ ---- was going on. I was in the other room when it first happened. |

Continuing his account, Dick said:

When I turned around Smith had the shotgun and I ran out. When I got to the doorway leading out of the room where Mr. Clutter was, I heard the gun go off.

So on the one hand Dick said he was in the other room when Mr. Clutter was shot. And yet he only had reached the doorway when Smith pulled the trigger.

Dick also described what happened to the Topeka reporter Ron Kull:

I saw only three of the Clutters shot, but I only saw one after she was shot - that was Nancy.

And yet in Las Vegas, Dick had the following exchange with Harold Nye:

| Dick: | I didn't think [Perry] was going to shoot the women. And then he shot the girl. | Harold: | You saw that? |

| Dick: | Yes. |

We see then that Floyd wasn't the only one who told a, well, a "complex" story. On the stand, Dick would have been a disaster.

Perry vs. Dick vs. Floyd

We said it's a question of which two career convicts and habitual criminals you want to believe. That's not quite true.

It's a question of which three career convicts and habitual criminals you want to believe.

We've heard from Floyd and Dick. So let's hear from Perry.

Perry's confession is one of the pivotal parts of In Cold Blood. Although the 20 pages - with the detectives' questions and comments interspersed - is rendered in verbatim quotes, Truman was not present. And we also saw that Truman embellished the telling for dramatic effect.

But Perry really did confess and it was taken down verbatim - not during the car ride from Las Vegas to Kansas - but by Lillian Valenzuela, the court recorder while Perry was in the Garden City jail. And his story does differ from Dick's.

As they pulled up to the Clutter property Perry mentioned his intentions:

| Perry: | I was getting a little ---- in my blood, as they say. So I was determined to talk Dick out of it. |

So Perry wanted to back out of the whole thing!

Now these words fit pretty well with what Truman wrote. Even when they realized there was no safe and all the family was tied up, Perry said he wasn't going to hurt anyone. But he had become disgusted with Dick, not only because it had all been a wild goose chase, but because Dick kept refusing to admit he had been wrong about the safe.

So Perry was going to humiliate the arrogant Dick. When they were in the basement with Mr. Clutter, Truman says Perry took the knife:

| Perry: | I said, "All right, Dick. Here goes." But I didn't mean it. I meant to call his bluff, make him argue me out of it, make him admit he was a phony and a coward ... But I didn't realize what I'd done ... |

So according to Truman, Perry went into a temporary blackout and didn't know what he was doing.

That's what Truman tells us. Perry's own story is a bit different - and far from exculpatory.

Once everyone was tied up, Perry said he asked Dick what were they going to do.

| Perry: | Dick said, "Like I said before. If we are identified, you know what it means. I'm in favor of getting rid of them." |

And now it seems that Perry had no objections:

... we was debating who was going to do what and who was going to start it. So I told him, "Well," I says, "I'll do it."

And he did it.

Note Dick and Perry were not debating about what they were going to do - they had already decided - but WHO was going to do "it". And at no point did Perry claim he didn't realize what he had done.

So let's summarize what we know so far about Dick and Perry and Floyd:

- According to Dick, Floyd planned the whole thing and Perry killed everyone.

- According to Floyd, Dick planned the whole thing and was going to recruit his friend Perry Smith.

- According to Perry, he wanted to abandon the whole thing and immediately realized there was no safe.

But there's more:

- According to Dick he only wanted to work as a farm hand for Mr. Clutter and would only burgle the safe if things didn't work out when he got out of prison.

- According to Floyd, he was certain there was a safe in the Clutter's old house, but he told Dick he didn't know if there was a safe in the new house, and so Dick believed there was.

- According to Perry, Dick was the one who insisted they get rid of the Clutters and both each killed two of the family.

Regardless of who planned what and who was getting what, the truth is that Dick had recruited Perry because he thought Perry was capable of killing people and so they could "leave no witnesses". And by Kansas law, if two people were involved in a felony and one of them killed someone during the course of the crime, both could be convicted of murder.

For all of Dick's protestations of how his plan was to leave everyone unharmed, his later garrulousness belied his benign intent. In his article in Male, he commented on the jurors after they delivered the verdict:

Right then I wished everyone of them had been at the Clutter house that night and that included the Judge ... I would have let it run out on the floor.

None at no time, heh, Dick?

As for which career convict and habitual criminal you want to believe, why bother?

The Further Adventures of William Floyd Wells

In any case, accessory or not, brains behind the plan or not, Floyd got the reward and a parole.

But Floyd had decided that crime had not paid well enough, and he continued to run afoul of the law. By 1965, he had ended up being sentenced to a 30 year stint for armed robbery in the Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman.

Floyd came to a rather strange end. Parchman Prison is a 28 square mile prison farm without boundary fences. So in principle you can just walk away.

In practice that has always been difficult. But in 1970 Floyd and two other prisoners decided to escape - but on a tractor, for crying out loud! Not unexpectedly the "break" was discovered, and everyone surrendered.

Except Floyd that is. He resisted and was shot dead by the guards.

Games Dick and Perry Play

[Warning! This lengthy section has a high nerd content. So to avoid the danger of attendant nerdism, you can skip to the next, less nerdy section, if you click here.

A scholar has pointed out how one particularly fascinating aspect of In Cold Blood is that it provides a real life example of the Prisoner's Dilemma. The Prisoner's Dilemma is a specific problem of game theory in which two partners in crime are apprehended and questioned.

Should they confess or stay silent?

First, why the heck should a criminal confess, anyway?

For one thing, if a criminal confesses he may get a reduced sentence. This might happen even if both co-perpetrators confess.

Then you have the situation where neither confesses. If they keep mum they might get off scott free. At the worst, they'll get convicted of a lesser tangential crime (in Dick and Perry's case this was parole violation and passing bad checks).