Al Jennings

The Real McCoy

Al Jennings

Telling the truth, sometimes.

The Truthful Al Jennings

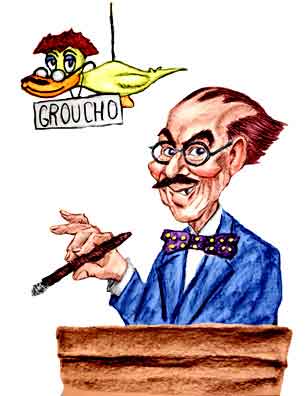

In 1951 a contestant named Alphonso Jackson Jennings appeared on Groucho Marx's popular quiz program You Bet Your Life. Al, then 87 and a resident of California, had been invited to the show because of his unusual career.

Al had been an Old West train robber. He had also been in many shootouts, he said, and wounded seven times. At one time, Al claimed he had a reward of $15,000 on his head, and his biggest haul was $75,000.

Eventually he said that he was betrayed by a horse thief that they used to stay with, and when he was finally apprehended he got shot up quite a bit. As to what happened next, Al said, "They sent me up for the period of my natural life and five years besides."

But, Al added, his life sentence was reduced to five years by President McKinley, and he only served three years and four months. He was then re-arrested on another charge, but was soon freed on a writ of habeas corpus. Then in 1907 he received a free and full pardon from President Theodore Roosevelt.

Groucho Marx

Al didn't say the secret word.

Al said... Al added ... Al claimed ...

We have to be honest. Some of Groucho's "guests-with-interesting-careers" were not always on the up-and-up. One of his contestants claimed to be 97 years old and had been one of Custer's soldiers during the campaign at the Little Big Horn. He survived because he had to remain behind to take care of a sick comrade.

Of course, over the years there have been almost as many - quote - "sole survivors of the Little Big Horn" - unquote - as there were soldiers in Custer's command. Unfortunately - or rather fortunately - further research has revealed that this "veteran" of the 7th Calvary was nearer 67 years old than 97. And his hometown had once voted him "The Biggest Liar in South Dakota".

Al, though, really had been a train robber in the last days of the Old West. He had even written an autobiography Beating Back which was co-authored with the then famous writer Will Irwin. Will's connections - he ended up being editor of Colliers - helped land the book as a serial in the Saturday Evening Post. The Post was one of the most widely circulated magazines and Beating Back garnered Al national fame.

As for Al, we can't say that he - like Mark Twain - told the truth mainly. Many of Al's stories are demonstrably false, and a popular pastime for Old West historians has been debunking Al's claims.

And yet we can't say that Al told the truth never. There are some stories that can be verified even though they sound like they came from an Old Western dime novel.

For instance, when Groucho asked Al why he had turned to a life of crime, Al simply replied, "They murdered my brother."

And yes, Al's brother, Ed, had been killed in a barroom gunfight in 1895. But the killer was acquitted and within a year Al's bitterness led him from being a respected attorney and a member of a prominent family of Woodward, Oklahoma*, to being the leader of an outlaw gang.

The Respectable Al Jennings

Al's dad, John Dela Fletcher Jennings, was originally from Tazewell County, Virginia where Al was born on November 25, 1863. John studied at Emory and Henry College in Virginia (not to be confused with Emory University in Atlanta) and became a Methodist circuit riding preacher.

In 1865 and after serving as a surgeon in the Confederate Army, John moved with his family to Marion, Illinois. The 1870 census reports that John was living with his wife Mary and four boys, John, Edward, Francis, and Alphonso. John, Jr., the oldest, was thirteen and Al, the youngest, was seven.

At Marion, John, Sr., added law to his multi-hatted career, and in 1872 he was elected county attorney. Despite his distinguished credentials, John had something of an ornery character. One citizen reported that John "was a rowdy among the rowdies, pious among the pious, Godless among the Godless, and a spooney among the women."

As the county attorney, John sometimes had an unorthodox way of dealing with suspects. One time a man named Field Henderson had been involved in an armed conflict called the Williamson County Bloody Vendetta. In brief the Bloody Vendetta was a McCoy-Hatfield type feud between families in the area. Field was suspected of shooting a local physician named Vincent Hinchcliff.

At one point during the brouhaha, Field went to John and asked him outright if he had been indicted for the murder. John told him yes, but to simply keep out of the way until the court convened. But John denied that Field had ever threatened him and said that Field "acted as gentlemanly as a man could."

In 1874, John decided to take his family back to Virginia and with them (according to some accounts) $900 in public money. But apparently his wife, Mary, died on the trip, and John remained in Manchester, Ohio, practicing law until 1880 when he moved to Appleton City, Missouri.

In 1889 and following stints in Kansas and Colorado, John decided to take part in the land rush in the unassigned lands in what was to become the state of Oklahoma. Although John claimed a homestead near Kingfisher (about 35 miles northwest of Oklahoma City), he wasn't really cut out to be a farmer.

Then in 1893, William Renfrow, Governor of Oklahoma Territory (which had split from Indian Territory in 1890), appointed John as probate judge in Woodward about 90 miles northeast further on from Kingfisher. Then in 1895 and after the events outlined below, John moved to Shawnee a bit east of Oklahoma City. He retired in 1901 to Slater, Missouri. He died in 1903.

Such a variable career was by no means unusual for the time. Professional men did not require the years of college training like today. In fact most professions didn't require college training at all. Although there was sometimes rudimentary licensing requirements, often you could just offer your services as doctor, lawyer, teacher, or whatever, and that was pretty much that.

And John's wanderings were not unusual either. This was, after all, the time of the Old West. Men would work in a town for a short time and then move on. Land was plentiful and new towns were springing up literally overnight.

Despite the clear documentation of the life of Judge Jennings, Al's formative years remain obscure. In 1874 when his dad decided to head back to Virginia, Al was only eleven years old. And although his dad remained in Ohio, we read that Al - quote - "completed his education" - unquote - in West Virginia. Later he attended the University of West Virginia and then passed the bar exam. Somewhat in support of this story is that the August 12, 1961 edition of the newspaper in Morgantown - the home of WVU - mentioned Al was an alumnus of the college.

During his lifetime, many news stories also spoke of Al as holding a college degree. Al, though, later wrote that although he did attend the WVU, he never graduated.

So what might have happened is that after his mom died, Al was sent to a boarding school in West Virginia since he had relatives there. Then he attended WVU for a while and then studied law, either at a law school or with an established attorney.

The Jennings brothers followed their dad westward but not necessarily by the same path. Stories have Al first moving to what was then the Chickasaw Nation. After residing in Purcell about 30 miles south of Oklahoma City, he then practiced law in East Texas and was admitted to the US Federal Courts in Paris, Texas, in 1890.

In 1891 Al relocated to El Reno (25 miles to the west of Oklahoma City). This was the county seat of Canadian County, and in 1892 he was elected county attorney. But after a defeat for re-election, he decided to join his dad and brothers in Woodward.

The Adaptable Al Jennings

On October 8, 1895, Ed and John, Jr., were the defense attorneys for a case involving some beer stolen from the train depot. Accounts differ on the number of defendants - some say it was only one boy; others that it was a group.

To assist in the prosecution, the Santa Fe Railroad had hired Temple Houston, the youngest son of Texas hero Sam Houston. Only thirty-five, Temple was already one of the most famous and flamboyant lawyers in the Southwest and one of the best.

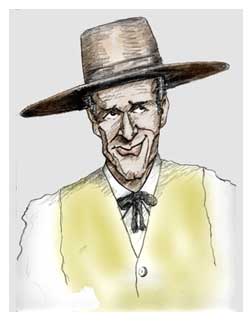

Temple Houston

He was one of the best.

We'll start off with Al's own account, but with a warning that it puts him more at the center of the events than the contemporary sources indicate.

Al was not part of the defense team, but he did say he was a courtroom spectator. Temple, Al said, was already irritated with the Jennings because he had lost a previous case to Ed. So now in the court Temple kept making snooty comments. "His attitude got on my nerves", Al said.

Finally Al had enough and called Temple a liar. Temple said Al was another. Al next says that Ed actually jumped up and slapped Temple, but others intervened before things got further out of hand.

That night Judge Jennings remonstrated with Al. Being a county official while also the father of such impetuous youths, he said, had put him in a difficult position. A repentant Al told his dad he'd patch things up with Temple.

Unfortunately Temple was in the barroom "drinking heavily, and "in no condition to hear reason". Al thought the best thing was to keep Temple and his brothers apart. He managed to locate Ed and told him to fetch John and bring him home.

Al said he was dozing off at the house when he heard someone calling his dad. Ed and John had been shot!

Suddenly John stumbled in. Although wounded he managed to gasp that Ed had been killed. Al hurried to the saloon and found Ed was not yet dead. But as Al held his brother's head in his hands, Ed breathed his last.

Heady stuff, surely. But although the basic gist of the story is correct, there's no indication that Al was actually in court or that he cradled the dying Ed's head in his arms.

That said, contemporary newspapers do state that during the beer-filching trial some personal remarks were made between the attorneys. Then the papers say that "the lie was passed".

This now archaic expression does indeed mean that during an argument one of the disputants called the other a liar. And at that time a man's word was his bond, and unlike today where lying is de rigueur for public figures even to being a point of pride, in the days of the Old West calling someone a liar was about the worst thing you could say.

From the stories it seems that it was indeed one of the Jennings that "passed the lie" - but the passing was prompted by a remark by Temple. The newspapers were not any more explicit than that.

Fortunately the most detailed account of the fracas is from historian Glenn Shirley. Glenn was one of the most careful and meticulous of western historians, and he had ready access to then hard to find documents. So when Glenn spoke, people listened.

Glenn tells us that Ed was arguing that the testimony of a witness was not admissible. Temple took exception and commented that the Jennings "must be grossly ignorant of the law". Here Ed "passed the lie" to Temple who "instantly resented it" and "an instant retort followed".

That others in the court intervened to prevent escalation of the dispute is also attested through the news accounts. But the stories don't make any mention of any physical altercation, and claims that there was actual gunfire don't appear to be correct.

At least there wasn't gunfire at that time. About 10:00 p. m. Temple was in the Cabinet Saloon (also known as Garvey's) when Ed walked in. Some witnesses said Temple saw Ed and calmly said he needed to talk. The two men sat down and spoke quietly.

Suddenly Ed jumped up. At this point, the action becomes obscure. But thirty seconds later, Ed lay dead on the floor with a bullet in his head, and John was staggering outside with a severe shoulder wound. Eventually he found his way home. Although some newspapers reported John was mortally wounded, he did recover.

Despite the affirmation on television and the movies, shootouts were not routine everyday occurrences in the Old West. They were serious matters and relatively infrequent. The gunfight at Woodward made the papers literally from coast to coast.

During the fight a friend of Temple's named Jack Love had come to his aid. So once the shooting stopped both Temple and Jack immediately walked to the sheriff's house and turned themselves in. They were charged with manslaughter and released on $2000 bail (about $60,000 today).

A coroner's jury couldn't determine who had actually fired the bullet that killed Ed - which wasn't surprising given that during the gunfight there was smoke billowing, bullets flying, men scrambling, and the lights got shot out. The jury referred the matter to the courts.

Temple and Jack went on trial the following May. The transcript of this trial has also disappeared, but there is a deposition from Walter Younger, a printer who was working late that night for the Woodward News. Walter was allowed to give his testimony early because he was leaving town before the trial.

Walter testified for the defense. What he said suggests to some that the shootout may not have been a chance happening.

Walter confirmed that he saw Al at the saloon that night but he left with a Derby hatted gambler known as "Handsome Harry". Walter then said that John came looking for a gun. So John wasn't originally armed.

On the sidewalk Handsome Harry - and no one knows who he really was - spoke with John for several minutes. Handsome Harry was also attempting to hide a Winchester underneath his Prince Albert coat. So some have wondered if the Jennings boys might have been actually gunning for Temple.

Unfortunately Walter's testimony is confusing. He had been asked to described what happened after he heard the gunfire and put the time of what he saw at about 10:30 p. m. - which was indeed after the shootout.

Certainly John could not have been shot in the shoulder and then casually walk up to a gambler who was hiding a Winchester and speak to him for several minutes. Walter's testimony is intriguing but it's hard to see how it's much help for the historian.

A particular point of doubt in the trial was who had actually killed Ed. Ed had in fact been hit in the back left part of the head. The defense argued that John, who was behind his brother when the shooting started, must have accidentally fired the fatal shot.

So with an abundance of confusing and contradictory testimony, the benefit of the doubt went to the survivors. Both Temple and Jack were found not guilty.

Although Al was certainly bitter about Temple's acquittal, he didn't immediately turn to crime. But he did leave town and found work as a ranch hand near what would soon be the city of Tulsa. This was the Spike-S Ranch of which we will hear of more later. John, with his severe wound, stayed in Woodward, but Frank headed off with Al.

Naturally Al gave a detailed account of what led him to go on the scout, as turning outlaw was called. The tale involves him being chased by a bunch of "long riders" who mistook him for a bandit. Al's horse was shot from under him and he was hit in the ankle.

Infuriated, Al began to charge the men on foot - remember he had a bullet lodged in his ankle - and at Al's fusillade the men scattered. Well, Al decided that if people were going to assume he was an outlaw, by golly, he would be an outlaw.

Regardless of whether Al is telling the truth mainly or not, we do know that Al fell in with bad companions. These were none other than Dan "Dynamite Dick" Clifton and Richard "Little Dick" West. Both Dicks had been members of the famous Bill Doolin Gang which had recently broken up. Perhaps because the "Little Dick Gang" just didn't sound right, the new band of outlaws was tagged the Jennings Gang. Two brothers named O'Malley rounded out the group.

Al and the rest didn't realize it, but Old West outlaw gangs mounted on horses, holding up a bank or train, and then disappearing into the countryside had become an anachronistic holdover of a rapidly fading era. Telegraph and telephones now permitted rapid communication between law officers, and the population had increased to where suspicious strangers were noted and promptly reported.

But what was worse for the bandits, railroads now reached into what were once inaccessible regions. Lawmen (and their horses) could move rapidly by train and only needed to disembark for the final leg of the chase. There was literally no place to hide.

The Outlaw Al Jennings

Contemporary records are not much help in tracing Al's whereabouts as an outlaw. From May 1896 until October 1897, news of Al is sparse. True, there were plenty of train and bank hold ups as well as stagecoach and store robberies and some were certainly due to Al and his gang. But the papers were reluctant - correctly so - to suggest any individuals were involved in a crime unless there was an eyewitness identification.

Fortunately, Glenn once more comes to the rescue. He managed to sift through various documents and newspaper accounts, as well as Al's own tellings. By cross checking the various stories, Glenn managed to sort things out as well as can be done. So we have a pretty good idea of how Al spent his summer vacation.

Al described his first train robbery as occurring a few days after he met with his father in January, 1896. But the robbery wasn't reported in the papers mainly because there was no robbery.

What the gang did was pile some ties on the track and set them on fire. They figured the engineer would see the flaming obstruction and stop the train. The bandits would then hop on board and get the loot.

But the engineer, recognizing the oldest trick in the book, opened up the throttle. The pilot - the "cow-catcher" - knocked the ties off the track, and the train barreled on through. Tough luck, Al.

Al then developed a more effective method of robbing trains - or rather, he adopted what was a tried and true modus operandi. Usually the gang would wait by a siding where a train would take water. Some of the gang would then climb over the coal car and cover the engineer and the fireman with their guns. Outside the train some other bandits would fire random shots in the air to keep the passengers in their seats.

Cash - bank transfers, payrolls, and the like - was kept in a safe in the express car. The outlaws would first try to get the clerk to open the safe, but usually the clerk didn't have the key or combination. So like as not, the safe had to be blown open with dynamite. Then while the bandits in the express car ransacked the safe and registered mail - often containing negotiable instruments - the others in the gang would rob the passengers of their money and valuables such as watches and jewelry. It's pretty certain that the gang was involved in a well-publicized robbery of August 16, 1897 at Edmond (now a northern suburb of Oklahoma City).

We also have various stories of how Al robbed small stores for paltry pickings virtually none of which can be verified by contemporary newspaper accounts. But the gang was identified as the men who robbed a post office and general store at Foyil, a small settlement a bit northeast of Tulsa. Al later admitted he was involved in this hold-up, and the gang was also suspected of rustling 400 head of cattle.

Finally everyone decided they had to take the Jennings Gang seriously. So the railroads put an offer of $100 for each gang member. Although this is far from the $15,000 that Al mentioned to Groucho, it was by no means chintzy. When Billy the Kid escaped from the Lincoln County jail in 1881, the New Mexico governor, Lew Wallace, offered a reward of $500. And this was for a fugitive who during the jailbreak had killed the two lawmen who had been guarding him.

So was Al's claim to Groucho about the hefty $15,000 reward utter nonsense? Is it one more example of Al's exaggeration of his exploits?

Well, yes and no. The monies offered for Al weren't $15,000, but neither were they only $100.

Rewards for bandits in the Old West were from multiple sources: federal, state, and territorial governments, railroads, livestock associations, and private citizens. One reporter toted up the amount offered for the Jennings Gang and came up with over $10,000 (he estimated about $7000 would probably be collected). So if we include the amount offered for the whole gang and cut Al some slack because he was remembering something from half a century past, Al wasn't that far off.

Finally, on October 1, 1897, Al and the gang decided to rob the Rock Island line near Chickasha. This is about forty miles southwest of Oklahoma City and in what was then the Chickasaw Nation.

The stories pretty much agree that Al and the gang kept to their established modus. They decided to hop on the train as it stopped on a siding, capture the engineer and fireman, and then blow open the safe and take the money. But although Al used plenty of dynamite, he placed the charge in a manner to be totally ineffectual. The explosion blew the car to splinters but left the safe intact.

With no money from the safe, the gang ordered the hundred or so passengers out of the cars. The bandits ended up with about $300 in cash plus sundry jewelry and watches. The story was they also got a bunch of bananas and a jug of whiskey.

This robbery, though, disproves the claims that Al was an Old West Robin Hood. If you believe Al he'd always leave a $20 bill with any rancher's wife who would give him a meal. But at Chickasha the gang's manner to the passengers was threatening and belligerent and when a man named Jim Wright refused to comply with the robbers' demands, they shot part of his ear off. Al said that was to show everyone they meant business.

But what marked this robbery as - to quote the papers - "one of the boldest train robberies in the history of the Indian Territory" - is the timing. It was carried out in broad daylight. Ironically that's really why Al got away with it. Trains were almost always robbed at night and so the railroads usually had guards only on the night runs. No one figured a gang would be crazy enough to hold up a train during the day.

Despite the relative success of this robbery, it was the beginning of the end. At one point Al's mask slipped from his face, and the conductor, a man named Darcey, recognized him. Al's name made the papers.

The Homely Al Jennings

And the papers weren't very charitable. They reported Al was 4 ½ feet tall and "very homely". They also provided some biographical background and stated he went to WVU for two years and then to the law school for the third year. He was also a drum major in the cadet corps and the professors always suspected it was Al when any pranks were played. According to one story a professor told Al "Why, you will disgrace your father and mother with the record of a bandit if you do not control yourself better." This sounds a lot like after-the-fact prescience but we read that Al himself liked to tell the story.

Al was still on the lam but evidently the reporters had some contact with him. At least the papers reported that Al indignantly denied any involvement. Why, he said, he was in Kansas City when the train was robbed.

Amazingly, Al's capture is actually something attested to by actual court records and sworn testimony. James Franklin "Bud" Ledbetter was a Deputy US Marshall who had been on Al's trail for some time. Then on November 29 Bud and his posse managed to track the gang to the Spike-S ranch.

The Spike-S ranch was not just a place where Al first found work after leaving Woodward. The owner, John Harless, was always being suspected of shady dealings and that he supplemented his own herds by picking random sampling from his neighbors' livestock. In fact, at the time of the Rock Island robbery, John was in jail on a charge of changing brands.

Mrs. Harless, though, was still there to offer the bandits the ranch's hospitality. Her brother Clarence and her daughter were also in the house along with a hired girl named Ida Hurst and a young boy.

By daybreak on November 30, Bud and the officers had staked out the house and managed to nab one of the O'Malley brothers who had been standing guard. Then when Clarence came outside the officers arrested him, too. Next Mrs. Harless made a trip out to the barn, and Bud stepped up and told her to go in and tell Al and the rest to come out. If the outlaws didn't agree to surrender, then everyone not in Al's gang must come out so they wouldn't get hurt.

Although some of the gang wanted to surrender, Mrs. Harless said the short bandit with the red hair - that was Al - said he'd rather die first. As Al grabbed a Winchester, Mrs. Harless left the house with her daughter, Ida, and the young boy.

What happened next was a classic Old West gun battle - at least according to Al. Naturally some writers (including the famed western historian Ramon Adams) doubt there really was a gunfight.

But while it is true that Al's version is exaggerated, the court testimony confirms that there really had been pretty much a classic Old West shootout. In fifteen minutes up to a hundred shots were fired. Some of the bandits were hit, including Al, and they decided to make a break for it.

Although Bud had stationed the posse members carefully around the house, Al and the others still managed to slip out the back and get away. We read that Bud had some hefty words to say about that.

The gang next took refuge at the home of a local rancher named Sam Baker. But uncomfortable with the possibility of harboring fugitives, Sam tipped off Bud and told him he would direct the boys down a certain road leading toward Arkansas.

On December 6, 1897, Al and the gang stole a covered wagon and following Sam's directions headed toward Arkansas. They were right on schedule when they drove into the hands of Bud and his posse.

The bandits gave up without a fight. They were first lodged in the Checotah jail and then transferred to Muskogee. Al had a bullet removed from his leg with the help of that fancy new technology called X-rays.

In January their dad visited Al and Frank in the jail. He said they should be courteous to their fellow inmates and told the officers all he wanted was a fair trial for the boys and if guilty, just punishment.

Al was the only member of the gang that had been definitely identified, both during the train robbery and during the shootout. So the lawyers for the others asked for a separate trial. The motion was granted, and their trial was postponed until October, 1898. But on May 29, Al went on trial for assault with intent to kill.

Al was found guilty. But there was also a charge of robbing the post office and store at Foyil. This trial included Frank and the O'Malley's. According to Al he was guilty but he fooled everyone - including his lawyers - and the gang was acquitted by a directed verdict.

Still, Al got five years for the assault charge. That seems a bit light for such a serious crime, but in those days the get-tough-on-crime guidelines weren't quite that tough.

Unless it's for train robbery. Almost a year later, on February 15, 1899, Al was convicted of robbing the train at Chickasha.

Al might have gotten off or at least had a mistrial except he testified in his own defense. On the stand he changed his story about being in Kansas City when the train was robbed and testified he was at home. But as detectives had staked out his house, they were able to prove that the story was untrue. This did not help Al's standing with the jury.

For the robbery Al was sentenced to the Ohio penitentiary for the remainder of his natural life. This may seem a stiff sentence when assault with intent to kill only landed him five years. But a recently enacted statute mandated a life sentence if during a robbery the life of a postal clerk - the guard in the railcar - was put in jeopardy, and if the bandits displayed deadly weapons.

In October, the rest of the gang went on trial. Seeing the way Al got whacked with life, they cut a deal and pled guilty. They each got five years.

Al's sentences were to be run consecutively. So once more we see that Al did indeed tell the truth when he told Groucho, he was sentenced for "the period of my natural life and five years besides."

To serve out his conviction for train robbery, Al was sent to the Ohio Penitentiary in Columbus. In that day and age the federal penitentiary system was still rudimentary and so state institutions often housed federal offenders.

It was in Ohio that Al met an inmate named William Sidney Porter. William, under the name O. Henry, soon became one of the most popular short story writers in America. It was from Al that Sidney got his story "Holding Up a Train".

Although off in minor details, Al's story about his release from prison was also substantially correct. His dad had petitioned to get Al's life sentence reduced to five years so as to be more in accord with the sentences of the other gang members. This wasn't just wishful thinking. By law the life sentence was mandatory, and during the trial the judge had indicated he would recommend such a commutation.

Then in June, 1900, President McKinley agreed with the request and reduced Al's sentence to five years. So Al was in error by a year. And Al was correct when he told Groucho he was sprung only after three years and four months, as the sentence reduction also included any time deducted for good conduct.

But there was still the assault charge, and after his release from Ohio in 1900, Al was sent to Fort Leavenworth Military Prison to serve it out. This was not the famous Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary which wouldn't open until 1903. Strictly speaking Al was not re-arrested like he told Groucho since he had already been convicted. But his transfer was effectively the same thing.

As far as Al finally getting sprung, once more we find that what he told Groucho was correct. Judge Jennings had retained the services of two of Kansas City's top attorneys, K. C. Price and Frank Sebreem. They filed for a writ of habeas corpus. If granted such writs require the government to deliver the prisoner to a court and provide justification as to why the prisoner is being held.

The argument in Al's case was that his two sentences should have run concurrently. With McKinley's commutation he then had two five year sentences. As he was sprung from one sentence, he should have been released from the other.

Writs of habeas corpus are usually filed for someone who is being held without charge, essentially telling the government to put up or shut up. However, it's rare for the writ to succeed if a prisoner has been convicted in a trial.

But in this case it did. Al was freed from Leavenworth in November 1902. The real irony is that although Al's original sentence had been for life, he was freed before his brother Frank. Frank, though, later got a parole.

Some stories on the Fount of All Knowledge tell us that Al was pardoned by Theodore Roosevelt in 1904. Nevertheless we again find that Al told the truth to Groucho that it was 1907. Although the contemporary news stories skim over the topic, we have the 1907 Annual Report of Charles Bonaparte, Teddy's attorney general. There we read in the section about pardons and commutations:

| Alphonso J. Jennings | Indian Territory, southern and northern (1) Assault with intent to kill; (2) mail robbery. | June 4, 1898. (1) Five Years in the United States Penitentiary at Fort Leavenworth; 2) imprisonment for life in Ohio penitentiary. (June 23, 1900, commuted to imprisonment for 5 years.) |

And there we read the recommendation:

"The petitioner was released from prison on Nov. 13, 1902, and if the uncontradicted statements contained in the papers filed with his petition are true, during the 4 years and 3 months which have since elapsed he has been a good citizen and a useful member of society. While it may be doubted whether he has been, on the whole, adequately punished for the very grave crimes of which he was guilty, I think that, under these circumstances, his civil rights ought to be restored; and I so recommend.

(Pardon recommended by the Secretary of War to restore civil rights.)

... and Teddy's actions:

Feb. 12, 1907. Pardon granted to restore civil rights.

And Frank had even gotten his pardon - the week before Al.

So why would Teddy give Al and Frank full free pardons? Well, we have to face it. If you have good connections, it helps. Those the Jennings brothers had.

And Al certainly seemed to have rehabilitated himself. After his release, he returned to Oklahoma and picked up his life. At first he moved to Lawton in the southwest corner of what was still Oklahoma Territory and married a young local lady Maude Deaton. Al briefly took a job as a salesman for a local firm but soon returned to the practice of law. From 1902 to 1907, his name often appeared as a defense attorney in some pretty high profile cases.

Then came the year 1908.

The Photogenic Al Jennings

Al's release from prison was almost coincident with the birth of the commercial film industry. In 1903 Tom Edison's film company - using technology he purchased from other inventors - produced The Great Train Robbery. One of the earliest motion pictures that used multiple scenes spliced together to form a connected narrative (not to mention over-acting), The Great Train Robbery also proved that the new entertainment was well suited to portray popular tales of the Old West.

Bill Tilghman

Fastest Camera in the West

Five years later a fellow named Bill Tilghman decided the public might like to see some real people from the Old West and not just East Coast cowboy (ptui) re-enactors. And none of those cowboys riding through the woodlands of New Jersey, either. His films would actually be produced on location in the Wild and Wooly.

There were few people better suited for the project. William Matthew "Bill" Tilghman along with Chris Madsen and Heck Thomas (the model for Richard Boone's character in the television series "Hec Ramsey") are well known to Old West history buffs as Oklahoma's "Three Guardsmen". Bill, Chris, and Heck had served as deputy federal marshals in the final years of Indian Territory and helped bring in the last of the major outlaw bands, particularly the Doolin Gang. So now Bill dug up funds to pay for some experienced cameramen and decided to make a film about a bank robbery.

Called (what else?) The Bank Robbery the film cast Al as (what else?) the bank robber. Filmed almost exclusively with long range shots in the newly established state of Oklahoma, the picture has no dialogue cards or explanatory titles. Other than being composed of the typical western scenes - a bank robbery, horse chase, and shootout - the film leaves modern viewers not quite sure what's of going on.

Richard Boone

(Hec Ramsey)

What is notable about this picture is the cast included some of the names that are among the most famous to students of the Old West. Of course, there was Bill (who was also the film's director), but we also saw Bill's friend Heck Thomas as well as gunfighter-turned-lawman Frank Canton. Even more of interest to western history fans is that the Comanche warrior, Quanah Parker, appeared as a member of the sheriff's posse.

Despite the film's now poor quality it's evident that all these men were getting on in years. You see even greater signs of Bill's maturity in "The Passing of the Oklahoma Outlaws" which he made in 1915. Then there's the 1921 movie, Jessie James under the Black Flag where James Edward James played his father. The younger Jesse had tubbed up considerably more than his dad ever had.

On the other hand although movies may have been the entertainment of the future, they weren't that common. Instead, it was usual to attend lectures. Impresarios would arrange tours of celebrities to stand up and talk to the audience on various topics. With his rhetorical training and flair for invention, Al took to the lecture platform mit gern and when times were slack he climbed into the minister's pulpit. Naturally he spoke of the error of his ways while boasting of his many and increasingly invented exploits.

The Loquacious Al Jennings

The year 1914 was truly Al's annus mirabilis. Not only was the serial Beating Back his - quote - "autobiography" - unquote - published as a book, but it was also made into a film. The movie was produced by a professional company and Al played himself.

So what do movie stars do? Yes, they go into politics.

So Al ran for governor of Oklahoma - and he didn't do too badly. He came in third in the Democratic primary and pulled in over 20,000 votes. The winner, Democratic candidate Robert Williams, polled 35,000 votes and went on to win the general election.

Al returned to making films, and in 1918, he formed his own company. His first movie, The Lady of the Dugout, had title cards and an actual plot. Al played himself in the fictional story (as did his brother Frank), but he was also smart enough to turn over the actual production to the professionals. The writer and director, William Van Dyke, made nearly 100 films in his long career in Hollywood.

As was common at the time, Al made personal appearances at the showings. But in 1918, Al was 55 years old and had neither the features of a Hollywood star nor at 5'1" the stature (one of the shortest of Hollywood's leading men, Alan Ladd, was a strapping 5'6"). Nevertheless Al continued to act even into his old age, but usually in bit and walk on roles.

Al continued to write and lecture. Then in 1919, Al's story about his friendship with O. Henry, Through the Shadows with O. Henry appeared as a serial and was also published as a book.

Since William - that is "O. Henry" - had died in 1910 we only have Al's side of the story and - surprise! surprise! - many of the claims are quite dubious. For one thing Al claimed he first met William in Honduras when they were both on the lam from the law (William had been accused of embezzling some bank funds in Texas, a charge he always denied).

But in Beating Back, Al tells us he spent the entire year of 1896, from January to the end of December, in either the Oklahoma or Indian Territories. Since he also said he then spent six months in Honduras and returned in August, that means he must have gone down to Galveston and caught a steamer to Honduras around March, 1897.

That William left the country to avoid his embezzlement rap is correct. He went to Honduras in 1895. But in January, 1897, William was back in the US. So the timelines don't fit. Nevertheless you will still read on popular informational websites that Al and "O. Henry" met in Honduras.

As the years rolled on, the western had become one of the most popular film genres and Al found that his reminisces were sought by the filmmakers and stars alike. Regardless of his tendency to stretch the blanket, Al was, after all, an authentic Old West outlaw. He was the Real McCoy.

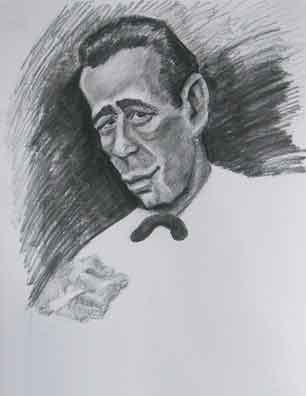

Al gave advice to Hugh ...

So Al and Maude relocated to California. As a film consultant, giving talks, and by taking occasional bit parts he made an adequate if not opulent living. We have photographs of him talking to a cowboy-suited Humphrey Bogart and giving pistol lessons to Hugh O'Brian - television's Wyatt Earp. Evidently Hugh had asked Al to give him pointers on how a real Old West gunfighter handled a shootin' iron. The gunfire alarmed Al's neighbors, and when the cops showed up they were amused to meet Hugh decked out in his Wyatt Earp duds and getting lessons from Al.

... and Humphrey

Not that Al always approved of how he was pictured. Starting in the 1930's one of the most popular radio shows was The Lone Ranger. In the episodes the Masked Man and his faithful Indian (ergo, Native American) companion, Tonto, would sometimes meet up with historical Old West characters. These included Calamity Jane, Annie Oakley, Ben Thompson, Ulysses S. Grant, Buffalo Bill Cody, Bat Masterson, Billy the Kid, Teddy Roosevelt, Pawnee Bill, Kit Carson, Sam Bass, John Wesley Hardin, and ...

Yep, Al Jennings.

No, Al didn't play himself in the 1944 broadcast and only learned of the show afterwards. It's likely the producers didn't realize Al was still around. What really miffed Al was at one point in the show the Lone Ranger beat him in a shootout (of course, the Lone Ranger shot the gun out of Al's hand). So Al sued the production company for defamation of character.

The news story about the trial gave a new generation an outline of Al's life, which given it's accuracy was evidently garnered from Al himself. We learn Al became an outlaw because two men shot his brother in the back and Al then chased them down and killed three of them and wounded another (where the extra two men came from we don't know). Then he robbed a store.

But when questioned under oath Al was a bit more factual. Yes, he had robbed trains but had never robbed a bank. Nor had he ever committed burglary.

It was Alexander Hamilton who helped establish the precedence that the truth is an absolute defense against libel. Al was indeed a rotten shot as one man who knew him personally avowed:

"I happen to know that Mr. Jennings can't hit a gallon can at twenty yards with aimed fire once out of ten times. I've seen him try."

Al lost the case.

Al continued to live in California, and in 1951 a movie, Al Jennings of Oklahoma, was released by Columbia Pictures. Very loosely based on Al's life, Al was played by Dan Duryea, a pretty big star at the time and one of the cast in the classic Flight of the Phoenix starring Jimmy Stewart, Richard Attenborough, and Hardy Krüger.

The movie did pretty well, and it must have brought Al some much welcome income. After all, Al was pushing toward his nineties.

Strictly speaking, we can't call Al a gunfighter. Bill O'Neal in his ground breaking Encyclopedia of Western Gunfighters defined a gunfighter as anyone who was in at least two verifiable gunfights from the end of the Civil War to the turn of the century. The key word here is "verifiable. By that criterion, Al was only in one shootout, that at the Spike S ranch.

Al died in Tarzana, California, December 26, 1961, just a month after Maude. He was 98. Life Magazine carried the story and got most of it wrong.

References

You Bet Your Life: Episode 69, Groucho Marx (Host), George Fenneman (Announcer), Al Jennings (Contestant), Wednesday 9:30-0:00 pm, April 25, 1951, DeSoto-Plymouth (Sponsor), Columbia Broadcasting System, Jerry Haendiges Vintage Radio Logs,

"Secret Word - Wall - Joe Anderson & 5 and Dime Store Clerk / Principal & German Housewife / Al Jennings & Phone Service Girl", You Bet Your Life, Audio File, Internet Archive.

"Survivors in Bighorn Folklore", Michael Nunnally, Little Big Horn History, April 26th, 2010.

Beating Back, Al Jennings (Author), Will Irwin (Author), Charles Russell (Illustrator), D. Appleton and Company, 1914.

The Writing Game: A Biography of Will Irwin, Robert Hudson, Iowa State Press, 1982.

West of Hell's Fringe, Glenn Shirley, University of Oklahoma Press, 1977, 1990.

"Al Jennings, 1863-1961, Lawyer, Bandit, Silent Movie Actor, Author", Marion Illinois History Preservation, Betty McDevitt, September 16, 2013.

"Bloody Williamson, Paul Angle, Knopf, 1952 (Reprint: University of Illinois Press, 1992; Knopf, 2014).

History of Williamson County, Illinois. From the Earliest Times, Down to the Present, 1876, With an Accurate Account of the Secession Movement, Ordinances, Raids, Etc., Also, a Complete History of Its "Bloody Vendetta," Including All Its Recondite Causes, Results, Etc., Etc., Milo Erwin, Marion, Illinois, 1876. Internet Archive.

A Standard History of Oklahoma, Volume 4, Joseph Bradfield Thoburn, American Historical Society, 1916.

Temple Houston: Lawyer With a Gun, Glenn Shirley, University of Oklahoma Press (1980).

"Testimony from a Famous Shootout", Robin Hohweiler, Woodward News, October 8, 2016.

"Glenn D. Shirley Western Americana Collection, 1850-2002", National Cowboy Museum.

"Getting Away with Murder on the Texas Frontier", Bill Neal, Texas Tech University Press, 2006.

Forty Years a Legislator, Elmer Thomas, University of Oklahoma Press, 2007.

"A Badman Who Went Straight - to Hollywood", Cecilia Rasmussen, L.A. Scene: The City Then and Now, The Los Angeles Times, August 14, 1995.

"Western Frontier Life in America", Richard Slatta, Department of History, North Carolina State University, January 19, 2006.

"Following the Frontier Line, 1790 to 1890", United States Census Bureau.

"Day Train Robbery", Kansas City Journal, October 2, 1897, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"Passangers All Stood Up in a Row", The Topeka State Journal, October 2, 1897, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"Hands Up", The Wichita Daily Eagle, October 2, 1897, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"The Great Edmond Train Robbery", Edmond Outlook, David A. Farris, February, 2010.

"Films of Al Jennings", Grapevine Video.

"Al Jennings Leader of the Original Gang That Couldn't Shoot Straight", True West, Marshall Trimble, January, 2018.

Oklahombres: Particularly the Wilder Ones, Evett Dumas Nix and Gordon Hines, Eden Publishing House, 1929 (Reprint: University of Nebraska Press, 1993,2018).

"Al Jennings, Oklahoma Bad Boy", Marshall Trimble, True West, February 5, 2016.

"The Lone Ranger Meets Al Jennings", The Lone Ranger, Brace Breemer (Actor: The Lone Ranger), John Todd (Actor: Tonto), August 7, 1944, Internet Archive.

"Al Jennings", Mark Boardman, True West, June 18, 2015.

"Alphonso J. Jennings (Al), Jay Robert Nash, Encyclopedia of Western Lawmen & Outlaws, Rowman & Littlefield. Copyright. March 21, 2016.

"Al Jennings: The Most Inept Outlaw of the Old West", Jay Robert Nash, Annals of Crime, 1992.

"Al Jennings", Internet Movie Data Base.

"Two Giants and a Romantic Renegade", Life Magazine, January 12, 1962.

"Al Jennings: Letter to the Editor", Zoe Tilghman, Life Magazine, February 2, 1962.

Al Jennings of Oklahoma, Dan Duryea (Actor), Gale Storm (Actor), Dick Foran (Actor), Ray Nazarro (Director), George Bricker (Screenwriter), Al Jennings (Author), Internet Movie Data Base.

"Cowboy Actor vs. Real Western Bad Man", Scott Harrison, Los Angeles Times, September 28, 2011.

"Al Jennings", Charles Eckhardt, Texas Escapes, July 21, 2008.

"Dangerous Dangerous Temple Houston", Clay Coppedge, Texas Escapes, August 17, 2017.

"Sam Houston's Lawyer Son Lived a Life of Style, Virtue, and Violence", Joe Holley, Houston Chronicle, September 18, 2015

"Lone Wolf of the Canadian", Jim Logan, Oklahoma Today, November 28, 2011

"Weekly Letter", Adaline Moore, Morgantown Post April 26, 1958

"Name Index to Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary Inmate Case Files, 1895-1931", National Archives.

"Prisoner at Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary. Al Jennings", National Archive Catalog.

"The Making of an Outlaw Image: Dangerous Al Jennings", Clay Coppedge of Oklahoma", Sue Schrems, Western Americana: History of the American West, December 31, 2009.

"List of Pardons, Commutations, and Respites Granted by the President During the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1907: Frank Jennings", Annual Report of the Attorney General of the United States: Vol. 1, p. 70.

"List of Pardons, Commutations, and Respites Granted by the President During the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1907: Alphonso J. Jennings", Annual Report of the Attorney General of the United States: Vol. 1, p. 71.

"Romancing the Robber", Jeff Nilsson, The Saturday Evening Post, December 11, 2014.

100 Oklahoma Outlaws, Gangsters, & Lawmen, Dan Anderson with Laurence Yadon, Pelican, 2007.

"Richard 'Little Dick' West", Bob Mead, Find-A-Grave, February 2, 2001.

"Jennings vs. United States, Court of Appeals of Indian Territory, October 26, 1899", The Southwestern Reporter, Volume 53, West Publishing Company, 1900.

Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation, Joseph J. Ellis, Knopf, 2000.

"Al Jennings", Find-a-Grave, October 27, 2003.

Historical Newspapers

"The Demon of Death", The Woodward News, Friday 1, October 11, 1895, Oklahoma Digital Newspaper Program, Gateway To Oklahoma.

"Their Trial is Brief", The Wichita Daily Eagle, May 15, 1896, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"Daylight Train Robbery", Guthrie Daily Leader, October 3, 1897, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"The Rock Island Hold-up", The Wichita Daily Eagle, October 2, 1897, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"The Rock Island Hold-up", People's Voice (Wellington, Kansas), October 7, 1897, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"Al Jennings Tells of Crimes in Suit Against Lone Ranger", Washington, D. C. Evening Star, September 28, 1945, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"Territorial Sketches", Guthrie Daily Leader, January 11, 1900, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"The Al Jennings Case", Daily Ardmoreite, June 14, 1900, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"Lawyers Fight in a Saloon", The Butler Weekly Times, October 17, 1895, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"Was a Fatal Fight", Fort Worth Gazette, October 11, 1895, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"Pleas of Guilty Entered", The Daily Ardmoreite, October 04, 1899, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"Houston and Meek - Attorneys at Law", Fort Worth Gazette, February 19, 1892, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"Over the Territory", The Guthrie Daily Leader, May 16, 1895, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"Al Jennings Regains Liberty", The Salt Lake Herald, December 7, 1897, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"Lawyers Fight in a Saloon", The Butler Weekly Times, October 17, 1895, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"Judge Jennings Visits His Boys", Indian Chieftain (Vinita, Indian Territory), January 20, 1897, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"The Jennings Case: Brief Sketch of the Crime and Trial", The Daily Chieftain Vinita, [Indian Territory], February 20, 1899. Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"Emptied their Guns", Wichita Daily Eagle, October 10, 1895, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"True Son of Sam Houston", The Evening Times (Washington, D. C.), October 10, 1895, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"Bullets in Court", The San Francisco Call, October 10, 1895, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"Al Jennings Free", The Daily Chieftain (Vinita, Indian Territory), November 17, 1902, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"Outlines of Oklahoma", The Wichita Daily Eagle, November 12, 1902, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"Al Jennings Here", The Chickasha Daily Express, December 30, 1902, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"City and Country", People's Voice (Wellington, Kansas), June 5, 1898, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"Jennings Boys Acquitted", Kansas City Journal, June 5, 1898, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"Not Guilty", The Daily Ardmoreite, June 8, 1898, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"Houston Critically Ill", Palestine Daily Herald, September 20, 1904, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"Isabel Items (Temple Houston the famous Woodward Lawyer was taken to the Topeka Hospital Last Week)", Barbour County Index, November 30, 1904, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"At Muskogee Al Jennings", The Daily Ardmoreite, March 3, 1898, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"Election Results: 1907-1992", Oklahoma Election Board.

"Duel on the West Side", Guthrie Daily Leader, October 11, 1895, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

"Railroad Bandit Tells His Own Story", Monroe City [Missouri] Democrat July 25, 1919, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

Motion Pictures

The Bank Robbery, Al Jennings (Actor), Frank Canton (Actor), Quanah Parker (Actor), Bill Tilghman (Actor and Director), Oklahoma Natural Mutoscene Corporation, 1908, Internet Movie Data Base.

Beating Back, Al Jennings (Actor), Caryl Fleming (Director), Will Irwin (Screenplay), Thanhouser Film Corporation, 1914, Internet Movie Data Base.

Passing of the Oklahoma Outlaws, Bill Tilghman (Actor), Bud Ledbetter (Actor), Roy Daugherty (Actor), Bill Tilghman (Director), Bill Tilghman (Screenplay), Eagle Film Company, 1915, Internet Movie Data Base.

Lady of the Dugout, Al Jennings (Actor), Corinne Grant (Actor), Frank Jennings (Actor), W.S. Van Dyke (Director), W.S. Van Dyke (Screenplay), Al Jennings Production Company, 1918, Internet Movie Data Base.

Jesse James Under the Black Flag, Jesse Edward James/Jesse James, Jr., Diana Reed (Actor), Franklin Coates (Actor), Franklin Coates (Director), Franklin Coates (Writer), Mesco Pictures, 1921, Internet Movie Data Base.

Return to Al Jennings Caricature

Return to CooperToons Caricatures

Return to CooperToons Homepage