Bobby das Messer

We all know Bobby Darin's finger-snapping song "Mac the Knife". So let's sing along:

|

Und der Haifisch, Der hat Zähne. Und die trägt er Im Gesicht. Und MacHeath, Der hat ein Messer. Doch das Messer Sieht man nicht. |

Bobby Darin |

Was? (To quote Goethe.) Das is "Mack the Knife"?

Aber ja doch, or rather, yes, indeed. "Die Moritat von Mackie Messer" ("The Ballad of Mackie Knife") was from a German musical Die Dreigroschenoper [pronounced "dee dry-GROSH-en-oh-per"] or The Threepenny Opera with words by the famous writer Bertolt Brecht and music by Kurt Weill. The premiere was in Berlin in 1928. So we see that at least in America "Mac the Knife" is one of those songs like "New York, New York" where people know the song but have forgotten the musical (or in the latter case the motion picture).

The unsuspecting Americans who listen to the German recordings of "Mac" are in for a surprise. They don't get a belted out big band swing song with its rousing ending. Instead, the music sounds like a moderately paced beer polka that finally peters out.

All right. Just how did a German "omph-pah-pah" song from the roaring twenties become one of the biggest pop songs of 1960's? Why, you might as well expect "Tiptoe Through the Tulips" to become a 60's hit!

It couldn't happen.

It just couldn't happen.

The truth is that Berlin of the 1920's rivaled Paris and New York in artistic innovation. Americans actually looked to Berlin as a model. The musical and motion picture Cabaret gives an idea of the last days of those carefree days of the fading Weimar Republic.

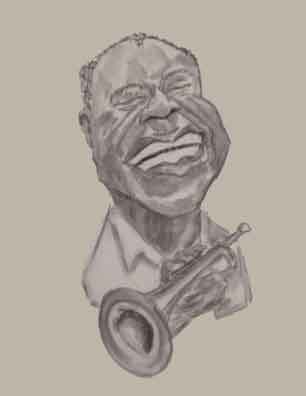

But the English translation of "Mac the Knife" that we all know and love was first recorded in 1956 by Louis Armstrong. As usual Louie's singing is great, and yet it's Bobby's version that everyone remembers. In fact some people mistake Louie's version for a later cover of Bobby's song.

Louis Armstrong

He sang it earlier.

Walden Robert Cassotto was born in New York City in 1936. His grandfather, Sam Cassotto, despite his friendship with big time gangster Frank Costello, never rose to the top ranks of gangsterdom. He was arrested for pickpocketing and sent to Sing-Sing where he died.

Bobby's grandmother, Polly, raised him like he was her son. In fact, that's what Bobby thought. His "sister", Nina, was really his mother, She had become briefly, well, "involved" with a college student who never learned he was Bobby Darin's father. Nina didn't tell Bobby the truth about his parentage until 1968.

From an early age it was clear young Robert had musical talent. However, he also had heart problems and was not expected to live beyond his mid-teens. If he did, the doctor said, he might be able to make it to his mid-30's. His family, though, remained supportive and even doted on the youngster.

With such a grim prognosis Bobby became determined to succeed while he could. When he graduated high school, he moved to New York and began performing in the small clubs and coffeehouses. His musical ability made it possible for him to join one of the groups of songwriters that cranked out songs for the pop singers of the 1950's.

Not that the songs were bad. Andererseits, Meine Freunde. Such songmeister conglomerates are where some of the best songwriters of the 20th century got their start. Today people remember Bobby the Entertainer but not Bobby the Songwriter. He wrote over 30 songs that were recorded either by him or other artists. One of the singers who used one of Bobby's compositions was none other than Buddy Holly.

Bobby's first recording - under his stage name - was released in 1956. Six more releases over the next two years made little impression on the industry. Then in 1958, Bobby wrote and recorded "Splish Splash". This hit #2 on the charts.

It was the following year, 1959, that Bobby became a true pop star with "Mac the Knife". It won him a Grammy Award for 1960.

However, a pop star, we emphasize, is not necessarily a rock star. Mac the Knife was not the stuff that kids were usually listening to. Instead, they preferred "Poor Little Fool" by Ricky Nelson, "Hound Dog" by Elvis, and later (bleah) "Last Kiss" by J. Frank Wilson. The next wave of rock - which included not only the hits of The Beatles and the Rolling Stones, but also the incomprehensible "Louie, Louie" - ended up pushing Bobby's songs into easy-listening category - something that no proper rock'n'roller would ever admit to liking.

Despite his accomplishments Bobby became a ready target of satire. A year after his Grammy Award, he was the subject of one of Mad Magazines "Celebrities Wallet" articles. Here we see Bobby keeping notes on when to snap his fingers while singing "Mac the Knife" (and when to sneer) plus photos of him with Frank Sinatra and Gina Lollobrigida with handwritten annotations on how they idolized him. Then there's a letter from his doctor advising him that the abrasion on his thumb comes from too much finger-snapping but the doctor can't give any explanation why Bobby's hat size has increased so much. There was also a note from Lloyds of London saying they could not underwrite his "greatness".

As the 1960's got underway, Bobby was simply not easy to pigeonhole. Was he a teen idol? An easy listening entertainer for Vegas? Was he simply trying to be the next Frank Sinatra? But if you asked Bobby what he liked, he'd say it was acting.

Fortunately, once pop music began to control the national economy, it became de rigueur for the singers to star in movies. Elvis was the one who really led the way, of course, (if you haven't seen Jailhouse Rock you haven't lived). Bobby's first movie role was in 1961. This was in Come September and although he wasn't the star (Rock Hudson was) he did have a major part and even won the Golden Globe Award for Best New Actor. And yes, he not only sings a song but even wrote the title tune.

So after this promising beginning, almost immediately Bobby began working on a new picture. This was Too Late Blues.

There were definite contrasts from his first movie. First, Bobby was the star, second, he doesn't sing, and third, the film was a drama.

We'll be upfront and say the reviews of "Too Late Blues" were less than stellar. Even today when the opinions have become more favorable (getting an 84% rating on a popular movie site), we find that Too Late Blues is one of those movies where it's not quite like Marmite. That is, it's not that you either love it or hate it. Instead, you either love it or hate it or don't know if you love it or hate it. But the movie's one virtue is, well, let's just say it's unforgettable.

WARNING!!!!!

SPOILER ALERT!!!!!

(To skip this synopsis, click here.)

Bobby plays a jazz pianist named John "Ghost" Wakefield. Ghost is an idealist. He cares nothing for commercial success, and during the opening credits we see him and his band playing for African American kids in an orphanage1.

Footnote

As it has not been possible to re-peruse the movie after a half a century, this synopsis must needs have be given by memory with some cross checking of various reviews and the odd trailer or two. But all in all what you'll read is pretty much what you get.

The group is a small combo that was quite typical after the Big Band Era. You have Ghost on piano, an alto sax played by Charlie (Cliff Carnell), Pete (Richard Chambers) on trumpet, Red (Seymour Cassel) playing bass, and Shelly (Dan Stafford) on drums. They mostly play "cool" jazz, and ghost's musicians are all the more remarkable since we see that they can play their instruments without moving their fingers.

In between making no money by playing idealistic music for charitable and worthy causes, Ghost and his band hang out at a poolroom run by Nick Bubalinas (Nick Dennis). Nick likes the guys but think they need to get real if they are ever going to be a success.

Later at a party we meet Ghost's manager, the crop-headed and tough-talking Benny (Everett Chambers). Benny shows up with a young lady named Jess played by Stella Stevens. Jess is a singer who is uncertain about her talent but Benny has the reputation of being a savvy manager who can transform fledgling singers and musicians into stars.

Jess and Ghost fall for each other. Naturally this irritates Benny who has eyes for Jess himself. But he's still Ghost's manager and arranges the band to play one of Ghost's innovative compositions (which we'll just call The Song) for a recording mogul named Milt (Val Avery). Ghost asks Jess to sing.

At first Milt the Mogul hates The Song since the lyrics aren't words but sound like "ooh-ooh-ooh-ooh" (the recording engineer thinks The Song stinks, too). Benny condescendingly explains that Ghost is an "idealist".

When Ghost doesn't hear any comment about his playing, he heads to the control room and rather surlily wants to know what's the beef. Seeing that Ghost stands up for his idealism, Milt the Mogul decides he likes The Song after all. He practically snivels his praise of Ghost's playing and Jess's singing. Ghost gets the contract for The Song but he must give over the rights.

After the session all repair in celebration to Nick's poolroom. There Benny dances with Jess and he tries to sweet-talk her to coming back to him. Jess is polite, but it's clear that she's thrown in with Ghost. Accepting the decision with poor grace and considerable overacting, Benny simply gives a sotto-voice but massively wide-mouthed "OK!". Then Benny heads off to talk with Tommy.

Tommy is a barroom tough played by Vince Edwards who was soon to gain fame as everyone's favorite grumpy TV doctor Ben Casey. Tommy thinks all musicians are druggies and is egged on by Benny's ambiguous answers to questions about Ghost ("Does he use drugs?" "Who knows?").

Tommy doesn't like Greeks either and he tries to show up Nick in a drinking contest where eating cheese is forbidden. Both Nick and Tommy get well-fueled and you expect trouble. But after the contest all seems well as both men drape companionable arms about each other's shoulders.

Then suddenly Tommy picks a fight with Ghost, sneering about a low-life musician who goes around with "a pocket full of needles". At the first swing, Ghost hits the floor right at Jess's feet. He pretends to be out while everyone in the band mixes in and takes care of Tommy.

As the guys help Ghost up he says he's all right. But Jess noticed that Ghost was never really hurt and could easily have gotten up and joined in the mêlée. Thinking she had fallen for a wimp, she nevertheless pities Ghost for his wimpiness.

Jess's compassion makes Ghost see red, and he yells at her. Now thinking Ghost is not only a wimp but rude, Jess asks Charlie to escort her to her apartment where she invites Charlie to come in which he does for the whole night.

Ghost, who always is kind of a grump, now goes to Milt the Mogul and says Milt can't have The Song. But no Song, says Milt, no record deal. Now the rest of the band sees that Ghost has thrown their future success away and leave in disgust. Only Charlie remains friendly and says if Ghost needs a good sax man, he's available.

Benny is satisfied that at least Ghost can't have Jess. Then when Ghost shows up asking for help, Benny sneers that the bigger the idealist the bigger the bum. And Ghost is a big idealist.

But Ghost is even worse than a bum. Ghost is a failure. And he, Benny, has no time for failures. Then make me a success, Ghost says.

OK, says Benny. He'll talk to the Countess2, an elderly lady "patron" who is, Benny says, "fairly attractive". She spends her fortune sponsoring the careers of talented young (and male) jazz musicians. He'll get the Countess to bankroll Ghost and set him up with some clubs. Ghost asks what he has to do. Nothing complicated, says Benny. Just the "usual" (wink, wink).

Footnote

The Countess is loosely modeled after the Baroness Kathleen Annie Pannonica de Koenigswarter, a member of European nobility and a patron of jazz in New York. However, there's no indication that Nica - as she was called - expected - ah - "favors" - as did the Countess in the movie. Instead Nica's patronage seems to have been a sincere gesture to promote jazz, particularly the not always popular bebop. Among her friends were Thelonious Monk and Charlie Parker. Nica gave Thelonious a place to stay in his last years of ill-health, and Charlie was actually watching television at her apartment when he was stricken with a fatal heart attack.

Ghost the Former Idealist now has money and he's playing in top nightspots. But he knows he's only a play-toy for a rich and elderly lady (actually Marilyn Clark who played the Countess was only 32 during the filming). And Ghost is just banging out crass commercial music as background noise for rich customers who don't give a flying hoo-hah about his artistry. Then finally irritated at Ghost's surliness, the Countess tells him she doesn't think much of his music. Ghost storms out.

Back at the pool hall, Ghost learns from Nick that the boys are together but playing in a low class dump. There he bumps into the still friendly Charlie. But Charlie warns him that the other boys might not be so happy to see him. Jess? Forget about her, says Charlie. She was no good. She hangs around a local bar and gives comfort to the customers. And when we say comfort we mean comfort.

Ghost goes to the bar where Jess is just about to comfort a big broad shouldered customer. He flattens the bruiser and does the same when the bruiser's friends jump in. So Ghost isn't a wimp after all!

With Jess in tow, Ghost heads to the club where the band is playing their crass commercial music. Jess is upset to be reminded of the days where she had so much hope and demands to know why he brought her there.

Shelly, the drummer, sneers when he sees "Mr. Idealist". He's going to play "Number 6", he says, showing that their music is now nothing more than what you get by punching numbers in a jukebox. They start to play Number 6.

But Jess begins to sing the non-words lyrics of The Song, and Ghost takes over on the piano. Gradually the others join in. Idealism has won out and we presume the band gets back together and all live happily after and as poor as ever.

Too Late Blues was the second film directed by John Cassavetes and he found himself in a fix similar to Ghost. In an interview John said that in order to make the film as he wanted to, he would have needed more time. But the studios loved the movie where the script was hammered out in a weekend and it was shot in six weeks. With those economics the movie would at least make some money. To this day the opinions about "Too Late Blues" remain mixed.

[To return to the beginning of the synopsis, click here.

Bobby's career only lasted about 17 years. He was never in great health and he pushed himself way more than he should. He died in 1973, only 37 years old and following heart surgery.

What surprises the casual listener who remembers Bobby Darin as the finger snapping Vegas crooner is his long time association with folk music. In fact his first commercial recording in 1956 was "Rock Island Line" which closely followed the singing of Leadbelly. Without being told beforehand it's not easy to realize you're listening to the singer of "Mac the Knife".

Folk music really seems to have been Bobby's favorite genre and he also ventured into Country and Western. Bobby would sometimes accompany himself on the guitar which he played quite well, and he was one of the first established performers to sing Bob Dylan's songs. He recorded "Blowing in the Wind" in 1963 when much of the American public was barely aware of Bob Dylan much less knowing that he'd win the 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature.

Usually Bobby stuck with the then-standards of what was called folk-rock: "Midnight Special", "Guantanamera", "If I Had a Hammer", "Mary Don't You Weep", "Michael Row the Boat Ashore", "If I Were a Carpenter". But "Simple Song of Freedom", which he wrote, sounded almost subversive.

But those were still innocent times. So Bobby does bowdlerize Hoyt Axton's "Greenback Dollar" a bit.

And I don't give a [pause] about a greenback, a dollar,

Spend it fast as I can.

Bobby had a good sense of humor and his skit on the Jack Benny Show was actually quite funny. Jack wanted to make a film about his life, but his manager and the studio heads said they needed someone younger if it was going to be a biography. So they asked Bobby to play the part and he spends a day with Jack trying to learn his mannerisms.

At one point Jack tells Bobby there's something he should tell him that nobody else knows. But Bobby has to promise not to tell a soul. Bobby agrees.

"Bobby," says Jack. "I'm - I'm really not thirty-nine."

Bobby is stunned.

"I haven't been so disappointed," Bobby admits, "since I found out Dean Martin drinks."

References and Further Reading

Roman Candle: The Life of Bobby Darin, State University of New York Press, 2010.

"Bobby Darin: A Life", Michael Starr, Taylor, 2010.

The Show I'll Never Forget: 50 Writers Relive Their Most Memorable Concert Going Experience, Sean Manning (Editor), Hachette, 2007.

"Songs Written by Bobby Darin", Second Hand Songs.

"Bobby Darin", Song Writers Hall of Fame.

"Too Late Blues", Torino Film Festival.

"Too Late Blues", Bobby Darin (Actor), Stella Stevens (Actor), Everett Chambers (Actor), Nick Dennis (Actor), Vince Edwards (Actor), Val Avery (Actor), Marilyn Clark (Actor), James Joyce (Actor), Rupert Crosse (Actor), Mario Gallo (Actor), Alan Hopkins (Actor), Cliff Carnell (Actor), Richard Chambers (Actor), Seymour Cassel (Actor), Dan Stafford (Actor), Allyson Ames (Actor), Johnny Bangert (Actor), Ralph Brooks (Actor), Morris Buchanan (Actor), Ivan Dixon (Actor), Ben Frommer (Actor), Slim Gaillard (Actor), Patti Newby (Actor), Joe Ploski (Actor), Cosmo Sardo (Actor), Don Siegel (Actor), June Wilkinson (Actor), John Cassavetes (Director, Writer, Producer), Richard Carr (Writer), David Raskin (Composer) 1961, Paramount, 1961, Internet Movie Data Base.

"Nica Goes to Hollywood", David Kastin, JazzTimes, April 25, 2019.

"On Commitment, Bobby Darin Became a Folkie Radical", Miles Raymer, AV Club, December 22, 2015.

"Celebrities' Wallets [Bobby Darin]", Arnie Kogen (Writer) and George Woodbridge (Artist), Mad Magazine, October, 1961.

"Too Late Blues", Variety, December 31, 1961.

"Too Late Blues", Rotten Tomatoes.

"The Jack Benny Program", January 28, 1964, Jack Benny (Actor), Bobby Darin (Actor), Norman Abbott (Director), Sam Perrin (Writer), George Balzer (Writer), Al Gordon (Writer), Hal Goldman (Writer), Columbia Broadcasting System, Internet Movie Data Base.