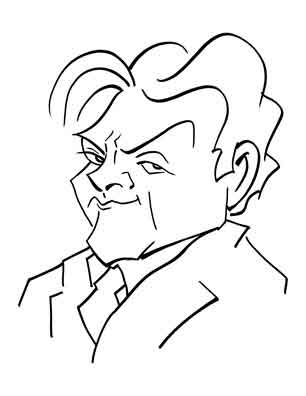

Edward G. Robinson

Edward G. Robinson

Not just another pretty face.

Why, we ask, do people like watching films where people get slaughtered by psychopaths and then as the end of the show rolls on, the psychopaths get bumped off as well?

Actually this mode of pleasure goes way back before films. In the late 1500's, London audiences loved watching Richard III massacre his friends and family between his long soliloquies. And in the end, Richard gets his just desserts. Later dime novels told of the (fictionalized) exploits of (real-life) outlaws Frank and his brother Jesse James. Then in the Victorian and Edwardian Eras, theater kept the criminals in view for these pre-cinema audiences.

Of course, Jesse had a leg up as he was a legend in his own time. There the fame - and the stories - were already in place. When Oscar Wilde was on his tour in America, he gave a lecture in St. Joseph, Missouri, on April 18, 1882. From his lodgings, Oscar wrote to his friend Norman Forbes-Robertson:

My dear Norman,

Outside my window about a quarter of a mile to the west there stands a little yellow house, with a green paling, and a crowd of people pulling it all down. It is the house of the great train-robber and murderer Jesse James who was shot by his pal last week1 and the people are relic-hunters.

Footnote

Jesse Woodson James and his brother Alexander Franklin James led a gang of bank and train robbers from 1866 to 1882. They operated from Missouri but ranged as far east as West Virginia, south to Texas, and as far north as Minnesota.

Jesse was finally killed by 20-year-old Robert Ford, a former gang member, as he was dusting off a picture in his home in St. Joseph Missouri. Jesse's wife, Zerelda (née Mimms), and his two children were in the house at the time.

Bob had been in communications with the governor of Missouri, Thomas T. Crittenden, but there is controversy on what kind of deal he and Governor Crittenden made. The official account is that Robert would assist in the capture of Jesse, obtain a pardon for his own crimes, and collect whatever rewards were due. The more controversial version is that Bob promised to kill Jesse if he would get a pardon. Bob was indeed arrested, tried, and sentenced to death only to receive a pardon. Ten years later Bob himself was killed in Creede, Colorado, by Edward O'Kelly. The motive was never clear, and Ed was sentenced to prison. Released in 1902, he was killed two years later in a fight with an Oklahoma City policeman.

After describing - with Wildean exaggerations - how much each household items was selling for - Oscar made one of his most famous quotes:

The Americans are certainly great hero-worshippers, and always take their heroes from the criminal classes.

Which brings us back to asking why do Americans take their heroes from the criminal miasma? Well, perhaps it's simply the culture as Samuel Johnson, the famed English writer and curmudgeon, suggested about the time of the American Revolution:

Sir, [Americans] are a race of convicts2, and ought to be thankful for anything we allow them short of hanging.

Footnote

Although the number of convicts transported to North America was "only" about 50,000, it would certainly have been more except for that pesky interlude called the American Revolution. After the Americans left Auntie England's bosom, that left Australia as the repository for England's miscreants. Ironically although the Australians are jokingly proud of the convict heritage, they have achieved far lower incarceration rates than in the United States - which isn't hard to do since the United States has the highest incarceration rate of any country in the history of the world imprisoning about 1 % of their population.

True, some of the popularity of the gangster tales also came about because of the fictionalization of the exploits where the crooks are painted as good guys and law officers as schmucks. The idealization of criminals early on gave rise to the outlaw ballads. You don't get many such songs anymore. Probably the last true outlaw ballad - which truth to tell has not found a wide audience - was "The Ballad of Pretty Boy Floyd3" - by Woody Guthrie. Regarding Choc's doing (as he was called), Woody had to stretch the blanket quite a bit4.

It was in Oklahoma City,

It was on a Christmas Day,

There was a whole car load of groceries

And with a note to say:

"Well, you say that I'm an outlaw,

You say that I'm a thief.

Here's a Christmas dinner

For the families on relief."

Footnote

Charles Arthur Floyd (1904 - 1934) was not not born in Oklahoma. He was born in Georgia and his family didn't move to Oklahoma until he was seven years old.

By far the most notorious crime for which Choc was accused was the infamous Kansas City Massacre. On June 17, 1933, Frank Nash, a notorious bank robber and reputed associate of Choc, was being transferred to Leavenworth by FBI agents. The men arrived by train at Union Station in Kansas City. As the men got into a car, gunmen - the number isn't clear - suddenly appeared and opened fire with Thompson machine guns. Frank and four FBI men were killed.

Choc, Vernon Miller, and Adam Richetti were accused of the crime. Vernon Miller was later murdered by persons unknown, and Choc was killed while fleeing from FBI agents in 1934. Adam Richetti had been arrested shortly before and was convicted of the crime. He was executed four years later.

The FBI did and still considers Choc the primary instigator. However, other crime historians question whether Choc was even there, and some even think that rather than attempting to free Frank, the Kansas City Massacre was targeting him to keep him from squealing.

There's no proof that Chock did anything of the sort. And with today's modern journalism it's kind of hard to sweep the negative aspects of the modern criminals under the rug. So don't hold your breath waiting for "The Ballad of Whitey Bulger".

But the first true gangster film in the modern sense has to be Little Caesar starring, yes, Edward G. Robinson. Released in 1931, this film not only made Edward a star, but did a strange thing to his career. On the one hand it typecast him although he never was really typecast.

Emanuel Goldenberg was born on December 12, 1893 in Bucharest, then part if the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In 1904 due to rising anti-Semitism the family immigrated to New York City. Edward loved the city and the country. At school he became interested in acting and studied at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts.

This was a time when Jewish literature had produced a number of successful novelists and playwrights and Edward began acting in Yiddish productions. New York was also the place to be for actors of talent. Edward soon moved to Broadway and began appearing in films by the time he was 33.

Let's admit it. If there was someone who was made to look like a Hollywood gangster it was Edward. Little Caesar became iconic as soon as it appeared. Four years later its basic plot was borrowed by novelist James T. Farrell for a fictional movie which features in the novel Studs Lonigan. At one point, Studs, the book's rather feckless protagonist, watches Doomed Victory whose plot follows Little Caesar closely. Of course, Studs, in typical Studsian fashion, misses the whole point of the movie's message.

Edward's next feature was Smart Money. Here he played less a gangster than a gambler where he appeared with another rising star named James Cagney.

Jimmy Cagney

Multiple Talents

Jimmy was a man of multiple talents. He was in fact an expert hoofer (as was George Raft), and Jimmy could play characters as diverse as George M. Cohan, Bottom the Weaver in Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream, and an American Coca-Cola executive living in what was then West Berlin. Eventually Edward played everyone from Nobel Prize winners to cowboys to Ancient Egyptians to monks5 and even himself. Ironically, Edward's last film was Soylent Green where he played a detective. Sadly he died later that year.

Footnote

Edward's versatility confused the panelists when he appeared as the Mystery Guest on What's My Line. The panelists were blindfolded and one of them asked if the Mystery Guest had ever played a priest. Edward responded truthfully "No". After Edward's identity was revealed, she asked why he said "no" since he had starred in Brother Orchid. Edward pointed out that he played a brother - a monk. Monks are priests only if in addition to taking their monastic vows they are also ordained. In other words, some monks are priests but not all priests are monks, and not all monks are priests but some priests are monks.

Actually Brother Orchid also is a gangster movie. But we won't spoil the plot for those who want to see it.

Edward's gangster roles would sometimes give him privileges not permitted other citizens. Edward was once given a personal tour of Alcatraz when it was a working penitentiary. There was a rule of silence on the Rock - or if not silence then decorum6. But when high profile guests were being taken on tours the prisoners would become rowdy, usually shouting epithets most rude. Edward found the episode amusing and one prisoner said during the tour Edward couldn't keep from smiling.

Footnote

The rule of silence at Alcatraz - which was a US Federal Penitentiary from 1933 to 1963 - was in force only during the first few years. As the rule was impossible enforce, it was emended - as chief guard Phil Bergen said - to a quiet system. At meals, in their cells, and at their jobs, the men were permitted to converse as long as it was in a quiet and orderly manner.

We said that Edward wasn't typecast. That's true but still he seemed to do his best playing someone outside the system. He played an Old West gambler and con man in The Outrage which also starred Paul Newman, Claire Bloom, and Laurence Harvey. But modern movie and television fans will most note the appearance of a young William Shatner as a disillusioned priest. And in The Prize - also starring Paul Newman - Edward played a dual role, one a Nobel Prize Winner and another a spy impersonating the Nobel Prize winner7.

Footnote

As part of the plot, Edward's character - the Nobel Prize Winner - suffers a heart attack. Paul revives him in a manner that is without doubt the most absurd method ever put to film. And if you do see the film, don't - as we say - try it at home.

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera

Edward was a help.

Edward also garnered fame for his lifelong interest in art. He not only painted (he was actually quite good) but he also became well known as a serious collector. His collection had paintings by the modern masters like Cézanne, Gauguin, and Van Gogh, of course, but he once went to Mexico to visit muralist Diego Rivera. While there he saw the art of Diego's wife, Frida Kahlo, and immediately bought some of her paintings. Edward's patronage was no little factor in Frida's later fame.

One complaint some modern critics have levied on today's celebrities is the uniformity of their appearance. The reasons proffered are legion. Many actors have the same make-up artists, we're told, they often sport similar coiffures, and yes, they may even share the same plastic surgeon.

Not to say these reasons are entirely wrong, but there also appears to be a true homogenization by the studios when selecting their potential stars. This not only sometimes makes it difficult to recognize who you're actually watching, but it plays havoc for caricaturists.

The key, of course, is to start off with the celebrities from the - quote - "Golden Age of Hollywood" - unquote. There with individualistic actors like Humphrey Bogart, Talulah Bankhead, Betty Davis, Katherine Hepburn, Orson Welles, Clark Gable - and of course, Edward G. Robinson, even artists of modest ability have a chance.

References

Little Caesar: A Biography of Edward G. Robinson, Alan Gansberg, New English Library, 1983.

The Encyclopedia of Hollywood Film Actors, Barry Monush, Applause, 2003.

"Why We Have Loved Gangster Movies for 100 Years", Bruce Chadwicko, History News Netowrk, September 15, 2015.

Oscar Wilde In America, John Cooper.

"Letters of Oscar Wilde", Rupert Hart-Davis, Harcourt, 1962.

Pretty Boy: The Life and Times of Charles Arthur Floyd, Michael Wallis, St. Martin's, 1992.

Little Caesar, Edward G. Robinson (Actor), Douglas Fairbanks Jr. (Actor), Glenda Farrell (Actor), William Burnett (novel), Robert Lee (Writer), Francis Faragoh (Writer), Mervyn LeRoy (Director), Warner Brothers, 1931, Internet Movie Data Base.

Smart Money, Edward G. Robinson (Actor), James Cagney (Actor), Evalyn Knapp (Actor), Kubec Glasmon (Writer), John Bright (Writer), Alfred Green (Director), Warner Brothers, 1940, Internet Movie Data Base.

Soylent Green, Charlton Heston (Actor), Edward G. Robinson (Actor), Leigh Taylor-Young (Actor), Stanley Greenberg (Writer), Harry Harrison (Novel), Richard Fleischer (Director), MGM, 1973, Internet Movie Data Base.

Brother Orchid, Edward G. Robinson (Actor), Ann Southern (Actor), Humphrey Bogart (Actor), William Burnett (novel), Earl Baldwin (Writer), Richard Connell (Story), Lloyd Bacon (Director), Warner Brothers, 1940, Internet Movie Data Base.

The Outrage, Paul Newman, Elke Sommer (Actor), Diane Baker (Actor), Edward G. Robinson (Actor), Howard Da Silva (Actor), William Shatner (Actor), Michael Kanin (Writer), Akira Kurosawa (Original Screenplay), Martin Ritt (Director), MGM, 1964, Internet Movie Data Base.

The Prize, Paul Newman, Claire Bloom (Actor), Laurence Harvey (Actor), Edward G. Robinson (Actor), Ernest Lehman (Screenplay), Irving Wallace (Novel), Mark Robson (Director), MGM, 1963, Internet Movie Data Base.

"Hollywood’s First Great Art Collector", Terry Teachout, The New York Times, July 16, 2015.

Forty paintings From the Edward G.Robinson Collection, March 4-April 12, Museum of Modern Art.

"There Are Actually Only 9 Men In Hollywood: What Is Going On?", Buzzfeed, February 11, 2017.

"Why do all celebrities look the same?", Hadley Freeman, The Guardian, July 15, 2006.

"Why Do So Many Male Hollywood Stars Look the Same?", Rae Alexandra, KQED, April 25, 2018.

"On The Rock: 25 Years on Alcatraz", Alvin Karpis and Robert Livesey, Beaufort, 1980.

The Life of Samuel Johnson, LL. D., Comprehending an Account of His Studies and Numerous Works, in Chronological Order; a Series of His Epistolary Correspondence and Conversations with Many Eminent Persons; and Various Original Pieces of His Composition, Never Before Published. The Whole Exhibiting a View of Literature and Literary Men in Great-Britain, for Near Half a Century, During Which He Flourished., James Boswell, Samuel Johnson, Henry Baldwin - Charles Dilly, London, 1791 (Text available at University of Oxford Text Archive.)

"Convict Labor During the Colonial Period", Emily Jones Salmon, Encyclopedia of Virginia.

Return to CooperToons Caricatures

Return to CooperToons Homepage