Muddy Waters

Muddy Waters

Mr. Morganfield

In 1964 when the Fab Four from England, the Beatles, first appeared on US soil, the reporters asked what they wanted to do. Why, meet Muddy Waters, of course.

The reporters expressed their ignorance of the gentleman in question - in fact one of them thought it was a town. Paul McCartney, the group's bass player, laughed. "Don't you know who your own famous people are here?"

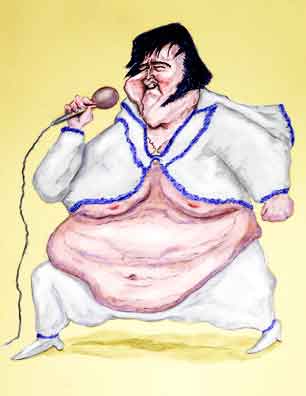

Not like Elvis

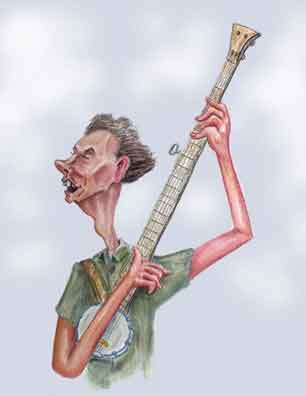

... nor Pete.

The answer, of course, was no, they didn't. Muddy Waters, the gentlemen in question, was largely unknown to the public. Nor was he a rock 'n roller like Elvis. Neither was he a musician from the folk revival like Pete Seeger. Muddy Waters played the blues.

McKinley Morgenfield was born April 4, 1913 in Rolling Fork, Mississippi. This was the Delta Country where if you were black you were poor and you worked as a sharecropper. Muddy's parents split up when he was only six months old, and he was raised by his mom and grandmother on the massive Stovall Plantation (now the Stovall Farms). There Muddy worked in the fields and never went beyond the third grade.

Music was a major part of the people's lives and if you wanted good music it had to be live music. Muddy learned the harmonica and guitar in an area which boasted master bluesmen like Son House and John Lee Hooker.

Opportunity for travel was limited - there were people who never went much more than 20 miles from where they were born. So music not only had to be live music but it had to be local music. Muddy quickly gained a reputation in the region. So in the summer of 1941 when Alan Lomax, director of the Folk Music Archive at the Library of Congress, came to Mississippi to make field recordings, everyone said he had to hear Muddy play.

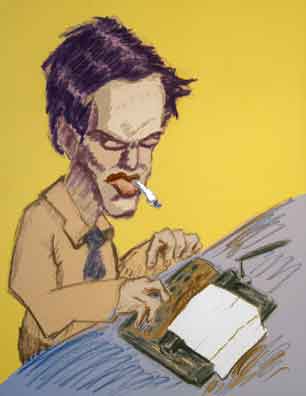

Alan Lomax

Alan not only recorded Muddy's songs but got him to talk about his life and background. Muddy was easy going about his personal doings and background, but a bit reticent about complaining about his hardships.

After Alan packed up his equipment and returned to Washington, Muddy went back to the fields. Then a year later he got a package in the mail. It was a recording of his songs. Muddy took it to the nearest bar and put it on the juke box. Hearing himself play, Muddy knew he was as good as the other performers who were actually putting out records. So he decided to try the big city and make it as a musician.

By the 1940's the Great Depression was over and there was work in Chicago. So in his off hours Muddy played at parties and in small bars on Chicago's South Side. If his playing didn't provide a regular salary, Muddy could always pass the hat.

But there was a wee bit of a problem. In parties where people were kicking up their heels or in clubs where people liked to gab, it was hard for Muddy's trusty acoustic to be heard. By now, of course, electrification was increasingly the norm, and so Muddy bought an electric guitar.

You could do a lot with an electric. It could play the usual riffs and progressions, but it could also squeal, moan, and screech as the player wanted. Muddy quickly mastered the new instrument. By 1950 he was drawing crowds to Chicago's Du Drop Lounge. He also had a record deal with a small jazz label.

These recordings crossed the Atlantic and were bought and played by the British Teddy Boys and Girls - the latter called "Judies". A chap named Keith Richards bought one of Muddy's recordings and then another young fellow named Mick Jagger saw Keith with the record. They struck up a conversation.

In America there had been resistance to rock and roll. Historians and sociologists debate the reasons back and forth - it was a music of rebellion, alien to the older generation of the "crooners" of the 1930's and '40's. But one undeniable reason was that rock-'n-roll had its roots in the black culture, and America still a strongly segregated land.

Parents went into spittle-flinging diatribes at the thought such "race-mixing" where their (white) daughters would attend dances where (black) singers like Richard Penniman - known professionally as Little Richard - would appear live while belting out his hit song "Good Golly, Miss Molly!"

| Good Golly Miss Molly, You sure like to ball. When you're rocking and rolling Can't hear your mama call. |

Today anyone seeing the news clips of indignant - quote - "civic leaders" - unquote - denouncing music that septuagenarians now dance to might wonder if they are actually seeing satire - a sort of early day Monty Python. Nope, this was actually what a lot of - again note the quotes - "adult leaders" - were saying. No wonder there was a widening generation gap.

In England things were different. It's not that parents liked the music their kids listened to. But segregation was illegal and anyone could go to any concerts or dance. The problem with Muddy's music, though, is it was sometimes too progressive. When he made his first trip to England in 1958 the audiences expected a solo performer whanging out Delta Blues on an acoustical guitar. Instead, he brought a whole band with him and everything was electrified - even the harmonica. Many of the crowd up and walked out.

But not the aspiring musicians. It wasn't just the Beatles who were fans of Muddy. When the Rolling Stones came to the United States (also in 1964), they met Muddy. Mick Jagger wasn't sure how the bluesman would take a gaggle of twenty-something English rockers (the bands name was even taken from Muddy's song "Rollin' Stone"). But Muddy encouraged them and later when they were in Chicago for concerts the Stones made sure to stop by where Muddy was performing.

Muddy's encouragement of young musicians was typical, and it wasn't just the Beatles and the Rolling Stones who cited Muddy as a major influence. Eric Clapton had Muddy tour with him as a guest performer and Johnny Winter produced one of Muddy's albums. Bonnie Rait said when Muddy would always joke with her. He had no resentment that other others who had adopted his electrified blues were more commercially successful.

Muddy didn't make to misquote Carl Sagan - millions and millions of dollars. But he was able to buy a nice home where he liked to lounge around with his kids and grandkids during the rare breaks from his travels. Muddy died in 1983, age 70.

Some years after the first recording sessions on the Stovall Plantation, Muddy happened to meet Alan again. Alan noted that Muddy was driving a Cadillac. Alan was still driving a Ford.

Muddy greeted Alan, "Hi, Lo."

References and Further Reading

The Land Where the Blues Began, Alan Lomax, Pantheon, 1993.

"Muddy Waters: 1915-1983", Robert Palmer, Rolling Stone, June 23, 1983.

"What Guitars Did Muddy Waters Play?", J. D. Nash, American Blues Scene, December 11, 2017.

"From Liverpool to New York: The Birth of Modern Rock", Tim Ryan, britishrockweebly.com.

"Rock 'n' Roll and 'Moral Panics' - Part One: 1950s and 1960s", Steve Williams, February 20, 2017, University of Southern Illinois.

Return to Muddy Waters Caricature